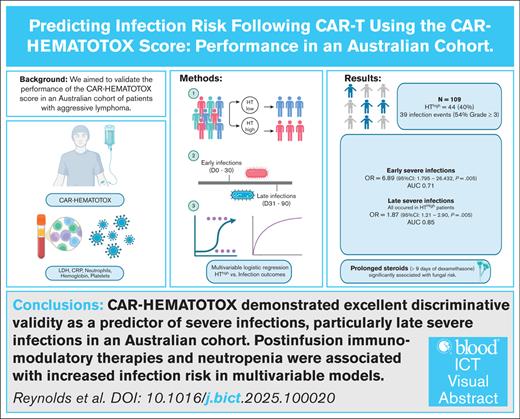

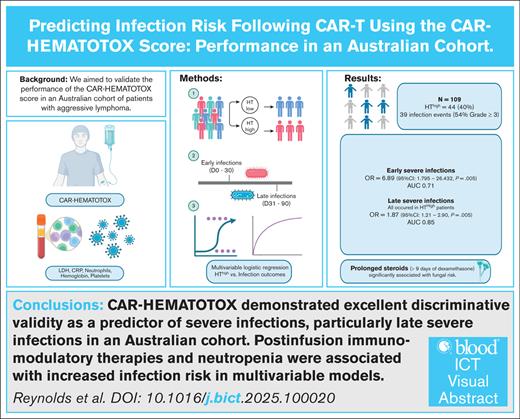

Key Points

CAR-HEMATOTOX scale performed best as a predictor of late, severe infections in an Australian cohort.

Postinfusion immunomodulatory therapies and neutropenia were associated with increased infection risk in multivariable models.

Visual Abstract

The CAR-HEMATOTOX (HT) score predicts prolonged neutropenia after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy. Patients with aggressive lymphoma with HT scores ≥2 (HThigh) have experienced higher rates of severe infections compared to patients with lower scores (HTlow). We aimed to validate HT’s prediction capability in an independent aggressive lymphoma cohort, treated with standard-of-care CAR-T, between January 2019 and September 2023. HT scores were calculated according to original methods. Infections were defined as microbiologically-confirmed or clinically-diagnosed. Severe infections were classified as CTCAE (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events) grade ≥3. Logistic regression evaluated HT’s association with infections within 90 days, and separately for early (day 0-30) and late (day 30-90) infections. Model fit was evaluated by area under the curve (AUC). Among 109 patients, infections occurred in 31 patients (54% grade ≥3). HThigh status was not associated with any-grade infections across day 0 to 90 (odds ratio [OR], 1.91; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.82-4.42; P = .13), but was significantly associated with severe infections (OR, 8.67; 95% CI, 2.30-32.68; P = .001), with very good discriminative validity (AUC, 0.74). HThigh status performed as a better predictor for late severe infections (AUC, 0.85), compared with early severe infections (AUC, 0.62). Multivariate logistic regression also identified tocilizumab (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.02-2.38; P = .041), prolonged neutropenia (OR, 11.95; 95% CI, 1.64-210.75; P = .001), and prolonged steroid (OR, 38.58; 95% CI, 2.05-725.91; P < .01) as significantly associated with infection. The relationship between HThigh and risk of severe infection was validated in our large B-cell lymphoma cohort. HThigh was an excellent discriminative predictor of late severe infections.

Introduction

The CAR-HEMATOTOX (HT) score predicts hematological toxicity and infection risk following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) treatment.1-4 It measures patients’ prelymphodepletion hemoglobin, platelets, ferritin, C-reactive protein, and lactate dehydrogenase to estimate baseline hematological reserve and inflammation.2 Patients with a HT score ≥2 (HThigh) have higher rates of prolonged neutropenia compared to patients with lower scores (HTlow),2,4,5 as well as higher rates of infections.1,4,5 HThigh status was associated with a higher incidence of severe infections, defined as infections requiring IV therapy or hospitalization, between day 0 to 90 in a cohort of patients with large B-cell lymphoma (L-BCL).1 Recent studies have shown infection incidence and severity decline from the early (day 0-30) to the late postinfusion period (day 30-90), suggesting potential changes in risk factors for infection over time.1,6,7 As a score that predicts prolonged neutropenia, HT may have additional utility as a predictor of late infection risk.2 This study evaluates HT score’s predictive efficacy for infections and its association with severe infections in the early and late postinfusion periods.

Methods

This retrospective study analyzed sequential standard-of-care CAR-T patients (January 2019-October 2023) at an Australian cancer hospital (HREC/8900), with data cutoff in January 2024. Patients were included if the 5 laboratory components of the HT score were available on the day of lymphodepleting chemotherapy. HT score, neutropenia duration, and steroid exposure were calculated per original methods.2 Data were also collected on 2 additional infection-risk factors identified in the sentinel HT validation analysis2: prolonged neutropenia (≤0.5 × 109/L for ≥14 days) and steroid exposure (≥10 mg dexamethasone daily for ≥9 days). Infections were classified using international consensus definitions, as either microbiologically-confirmed, or clinically-defined without a known pathogen.8 Fungal infections were defined according to the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MRSG) criteria.9 Severe infections were defined as grade ≥3 by Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) criteria, requiring hospitalization or IV antimicrobial therapy.10 Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector–cell associated neurotoxicity (ICANS) were graded according to American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy criteria. All patients received routine antiviral and antipneumocystis prophylaxis, but not fluoroquinolones (supplemental Table 1). Cytomegalovirus surveillance was not routine.

Logistic regression was used to evaluate the performance of the HT score in predicting early (day 0-30) and late (day 30-90) severe infections. HT score was evaluated as a categorical variable (HThigh vs HTlow) for the primary analysis, whereby HThigh was a HT score ≥2. The performance of the HT score as a continuous variable (0-6) was also examined. Discriminative ability was assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC). We evaluated whether additional clinical variables improved the performance of the HT score in predicting early and late infections. Variables of clinical interest, including host factors (age, prior transplantation, prior CAR-T), and post–CAR-T factors (CRS, ICANS, intensive care unit admission, cumulative tocilizumab and steroid exposure, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor administration) were individually added to a baseline model containing the CAR-HT score. We used forward selection, adding variables sequentially to a baseline model (HT) and retaining those that significantly improved model fit by likelihood ratio testing. Firth penalized logistic regression was applied throughout to reduce small-sample and low event-rate bias. Results are expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Sensitivity analysis was then undertaken using a Cox proportional hazards model, to account for censoring and competing risks. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 28 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and R studio.

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Demographics

HT parameters were available for 109 patients (median age, 64 years; interquartile range [IQR], 57-69) receiving axicabtagene (n = 64) or tisagenlecleucel (n = 45) for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma, with a median of 13 months follow-up (IQR, 7-25). Five (4.5%) patients died during the study period. Table 1 demonstrates the comparable demographic, disease and treatment characteristics between our validation cohort and the original HT L-BCL study.

HT scores

HT scores ranged from 0 to 6 (median, 1; IQR, 0-1; supplemental Figure 1). Significant differences were observed between HThigh and HTlow scores across all score components except neutropenia (supplemental Table 2). The 2 HT risk groups did not differ significantly in baseline demographics, prior treatments, or incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (supplemental Table 2). A HThigh score was significantly associated with prolonged neutropenia ≥14 days compared to a lower score (OR, 2.94; 95% CI, 1.13-7.65; P = .03). HThigh was not significantly associated with clinically-actionable CRS (grade ≥2; OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.51-2.36; P = .81) nor the occurrence of ICANS (grade ≥1; OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.47-2.32; P = .92).

Infection events

Thirty-nine infection events (21 events grade ≥3, 54%) occurred in 31 patients (36%) between day 0 and 90, reflecting a cumulative incidence of 28.4% (95% CI, 20.2-37.9) and an incidence rate of 4.1 infection events per 10 000 patient-days in the study period (day 0-90). Early infections (day 0-30) were more common at 22% cumulative incidence (95% CI, 14.6-31.0) compared to new late infections after day 30 in patients previously without infection (cumulative incidence, 8.2%; 95% CI, 3.4-16.2). Microbiologically-defined infection accounted for 77% (30 events) of infection events. Bacterial infections were most common (14/39 events, 36%), followed by viral (28%) and fungal infections (13%). Nine (23%) infection events were clinically-defined infections. The distribution of microbiologically-confirmed vs clinically-diagnosed infections by day 0 to 30 compared to day 30 to 90 is displayed in supplemental Table 3. Our cohort experienced significantly fewer clinically-diagnosed infections, than the HT development cohort (Table 1). The relationship between infection events and other treatment-emergent adverse events is summarized in supplemental Table 4.

HT score and all infections (day 0-90)

HThigh status was not significantly associated with any-grade infection in our cohort between day 0 to 90 (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 0.82-4.42; P = .13), but was significantly associated with a severe (grade ≥3) infection in this time period (OR, 8.67; 95% CI, 2.30-32.68; P = .001), with good discriminative validity (AUC, 0.74). Considering infection subtypes, HThigh status was significantly associated with bacterial infections in the 90-day postinfusion period (OR, 4.59; 95% CI, 1.15-18.42; P = .03). HThigh status was not associated with viral infections (P = .20) or fungal infections (P = .10).

HT score and early infections (day 0-30)

The performance of HT score was then evaluated for separate time periods. HThigh status was significantly associated with any-grade (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.02-6.48; P = .046) and severe early infections (OR, 6.89; 95% CI; 1.795-26.432; P = .005). However, it demonstrated only moderate discriminative validity (AUC of 0.62 and 0.71 for any-grade and severe, respectively) in delineating between patients who did and did not experience early infection (supplemental Table 5). Further analysis of HT’s association with viral, fungal, and bacterial infections in the early postinfusion period was not performed due to small individual event numbers.

HT score and late infections (day 30-90)

After day 30, HThigh was not significantly associated with all-grade infections (OR, 1.84; 95% CI; 0.62-5.51; P = .28). Notably, all late severe infections, however, occurred in the HThigh group. HT was therefore only evaluated as a linear score between 0 and 6 in association with late severe infections. Higher HT scores were significantly associated with higher risk of severe infection (OR, 1.87; 95% CI; 1.21-2.90; P = .005), with very good discriminative validity (AUC, 0.85). Further analysis of HT’s association with viral, fungal, and bacterial infections in the late postinfusion period was not performed due to small individual event numbers.

Other predictors of infection risk

Predictors of severe infections

In a multivariable model of all-grade early infections including the CAR-HT score, cumulative corticosteroid dose, and cumulative tocilizumab exposure prior to infection, the model showed significantly improved fit compared to the CAR-HT score alone (likelihood ratio test P = .023). However, none of the individual predictors reached statistical significance, likely reflecting limited power and correlated treatment exposures. For early severe infections, tocilizumab exposure prior to infection was significantly associated with increased likelihood of infections (OR, 1.52; 95% CI; 1.02-2.38) in a multivariable model of HT score, tocilizumab, and corticosteroids (likelihood ratio test P = .006). After day 30, the presence of an infection between day 0 to 30 (OR, 14.23; 95% CI; 2-217; P = .007) and prolonged neutropenia (OR, 11.95; 95% CI, 1.64-210.75; P = .01) was associated with late infections in multivariate analysis, but should be interpreted cautiously given the wide confidence interval due to a low number of severe infections. These findings were replicated in a Cox proportional hazards model (supplemental Table 6)

Predictors of viral and fungal infections

Risk factors for viral and fungal infections across the whole study period were also evaluated. There were no significant predictors of any-grade viral infections on univariate analysis. Multivariable regression for fungal infections identified prolonged steroids as the most significantly associated with fungal infections (OR, 38.58; 95% CI, 2.05-725.91; P < .01; supplemental Table 7), controlling for the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) HT score, and prolonged neutropenia. Prolonged steroids were entered as a variable to reflect immune-related adverse events because of high collinearity between the occurrence of CRS, ICANS, tocilizumab, and the need for prolonged steroids. The wide CI likely reflect the small number of fungal events and limited sample size but do not negate the association. Further analysis, detailed in supplemental Table 7, demonstrated that receiving ≥100 mg dexamethasone equivalency cumulatively was discriminative of fungal risk (AUC, 0.74) as prolonged steroids exposure ≥10 days used in the original HT models (AUC, 0.77).

Discussion

Unlike the original L-BCL cohort, HThigh did not predict all-grade infection risk across the study period (day 0-90) and performed better throughout as a predictor of severe infection. We found no significant demographic differences between the original and validation cohorts, nor between our HThigh and HTlow groups, to account for this effect. The etiology of postinfusion infections differed between cohorts, with significantly more clinically-diagnosed infections in the development cohort.1 Differences in the retrospective attribution of post–CAR-T fever and febrile neutropenia may potentially account for these results, and underscores the importance of validating models across different populations with standardized definitions of infections, particularly microbiologically-defined infections.

HThigh was significantly associated with severe infections across the study period (day 0-90). This association remained significant when early (day 0-30) and late (day 30-90) periods were evaluated separately. The significant association between HT score and severe infections has been demonstrated in L-BCL, myeloma, B-ALL, and mantle cell cohorts,1,4,5,11 as well as a recent Danish multicenter validation study in L-BCL that looked exclusively at severe infections.12 In our study, HT score demonstrated very good discriminative validity in predicting late, severe infections (AUC, 0.85), but performed much more modestly in the early postinfusion period (AUC, 0.62). This may be explained by the type of infections that occurred in each period. Late severe infections were predominantly bacterial (50%), in contrast to early severe infections (36% bacterial). Bacterial infections were strongly associated with HT score in other studies, likely due to the intercorrelation between HT score, neutropenia, and bacterial infection risk.1,2 Prolonged neutropenia was also the most strongly associated with late severe infections in our study. Thus, HT has potential to help identify patients prior to infusion who will have persistent risk for severe bacterial infections, often due to the development of prolonged neutropenia, despite the general decline in infection incidence and severity after CAR-T infusion.

Previous studies have postulated that fluoroquinolone (FQ) prophylaxis significantly reduced the incidence of severe bacterial infections in HThigh patients. Interestingly, our rates of severe bacterial infections across the cohort (7% of patients), in the absence of antibacterial prophylaxis aside from trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole thrice weekly starting at neutrophil recovery, were comparable to rates reported in the HT development cohort who received FQ prophylaxis (9%).1 Direct comparison of the patients between cohorts who developed severe bacterial infections was beyond the scope of this validation study. Prospective studies are needed to validate the utility of FQ prophylaxis for patients who underwent CAR-T therapy, considering local bacterial resistance patterns and sepsis management pathways.

Similar to the original L-BCL cohort, and a recent validation,12 HT score was also not significantly associated with the risk of fungal and viral infections in our cohort.1 No significant predictors of viral infections were identified in our analysis. However, prolonged steroid exposure was significantly associated with risk of fungal infection, consistent with recent larger cohort findings.13 Immune-related adverse events and their treatments are frequently posited as risk factors for fungal disease in patients undergoing CAR-T therapy.14,15 However, the low incidence makes identification of risk factors difficult via regression modeling, as reflected in the wide CI.16,17 Our further analysis identified a lower threshold of risk: 100 mg of dexamethasone equivalency or ∼3-days of typical treatment for severe ICANS,18 which requires validation in future studies.

This study provides, to our knowledge, the largest independent validation of HT’s association with infection in aggressive lymphoma beyond Europe and the United States. It underscores the relationship between HT score and severe bacterial infections, with improved performance for predicting late severe infections. These findings support the need for tailored strategies to prevent late infections after CAR-T therapy, especially for patients who no longer reside near their treatment center after day 30. The CAR-HEMATOTOX score offers a pragmatic tool to identify such patients and guide additional measures, which might include individualized approaches to neutropenic fever management or, in select contexts, additional prophylaxis strategies. Limitations of this study include its retrospective design, reducing cohort size due to missing HT parameters. Ongoing validation efforts with standardized infection definitions will enhance personalized infection-risk prediction during CAR-T therapy.

Acknowledgment

G.K.R. is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council PhD scholarship (2013970).

Authorship

Contribution: G.K.R. designed the research, performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; M.R.D. performed the research and reviewed and drafted the manuscript; S.V. assisted with data analysis and reviewed the manuscript; O.C.S. designed the research; B.W.T., M.A.A., and K.T. designed the research and reviewed the manuscript; and S.J.H. and M.A.S. designed the research and reviewed and drafted manuscript.

Conflicts-of-interest disclosure: M.A.S. has grants or contracts with the National Health and Medical Research Council, Merck, and F2G; consulting fees from Pfizer, Takeda, Gilead, and Merck; advisory board membership with Roche and Pfizer; and leadership role on Australian Society of Infectious Diseases Immunocompromised Host Special Interest Group. M.A.A. has royalties or licenses with The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research; receives honoraria from AbbVie, BeiGene, Sobi, Specialised Therapeutics, Janssen, Roche, AstraZeneca, Gilead, Novartis, CSL, and Takeda. G.K.R. receives honoraria paid to institution from Janssen. B.W.T. receives grants paid to institution from Merck Sharp and Dohme, Seqirus, and Sanofi; honoraria paid to institution from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Gilead; and advisory board paid to institution from CSL-Behring, Takeda, and Moderna. S.J.H. receives grants from Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), GSK, Jannsen Cilag, and Haematologix; consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene/BMS, GSK, Janssen Cilag, Novartis, Roche, Genetech, HaemaLogiX, EUSA Pharma, Terumo BCT; honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene/BMS, GSK, Janssen Cilag, Novartis, Roche Genetech, HaemaLogiX, EUSA Pharma, Terumo BCT; and advisory board fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene/BMS, GSK, Janssen Cilag, Novartis, Roche Genetech, HaemaLogiX, EUSA Pharma, and Terumo BCT. M.R.D. receives honoraria from Novartis and Kite/Gilead. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gemma K. Reynolds, Department of Infectious Diseases, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, 305 Grattan St, Melbourne 3000, VIC, Australia; email: gemma.reynolds@petermac.org/ gkreynolds@student.unimelb.edu.au.

References

Author notes

Deidentified data are available from the corresponding author, Gemma K. Reynolds (gemma.reynolds@petermac.org), on reasonable request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.