Key Points

CVRFs predict worse overall survival and thrombosis in MPNs but not progression-free survival to MF or acute leukemia.

The HR of CVRF on thrombosis is decreased in patients with MPNs compared with non-MPN controls.

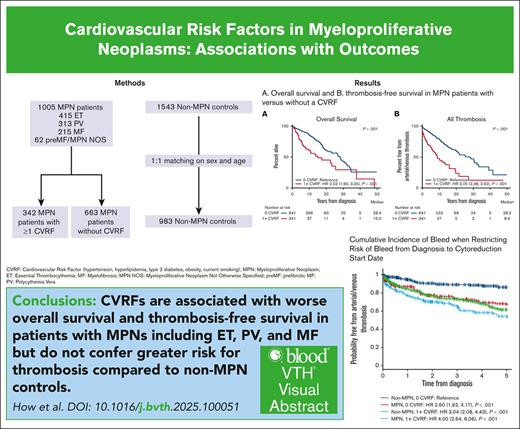

Visual Abstract

Cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs) are important modifiers of thrombosis in patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET), polycythemia vera (PV), and myelofibrosis (MF). We performed a retrospective cohort analysis evaluating CVRFs in 1005 patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Hematologic Malignancies Data Repository from 2014 to 2023. We also included a non-MPN group of 1543 age- and sex-matched controls with no known diagnoses of hematologic malignancies to evaluate whether CVRFs differentially affected outcomes. CVRFs were identified through International Classification of Diseases codes for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), current smoking, or body mass index ≥30 before MPN diagnosis. CVRFs occurred in 34% of patients with MPNs. Patients with MPN with ≥1 CVRF had increased risk of death (hazard ratio [HR], 2.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9-3.35) and arterial/venous thrombosis (HR, 3.05; 95% CI 2.39-3.92). Within MPN subtypes, patients with ET, PV, and MF who had CVRFs also demonstrated worse overall survival and thrombotic outcomes. Among CVRFs, only DM2 predicted worse thrombotic outcomes in patients with MPNs. The HR of CVRF on thrombosis was decreased in patients with MPNs compared with non-MPN controls (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.36-0.86). Looking at ET, PV, and MF specifically, the presence of a CVRF also had less of an impact on thrombotic risk in ET compared with controls (HR, 0.35; P = .019); no interactions between MPN diagnosis and CVRFs were seen in patients with PV and MF. Our results underscore both the necessity of managing CVRFs in MPNs to improve patient morbidity and mortality and the need to ameliorate thrombotic risk with measures beyond addressing CVRFs.

Introduction

Philadelphia chromosome–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are chronic neoplasms characterized by the expansion of mature myeloid cells. A unique feature of MPNs is an increased risk of thrombosis, which is greatest in polycythemia vera (PV) but also relevant in essential thrombocythemia (ET) and myelofibrosis (MF).1 The pathophysiology of thrombosis is related to a complex interplay between qualitative and quantitative defects in blood cells as well as elevated inflammatory cytokines from dysregulated JAK/STAT signaling.2 As a result, arterial and venous thrombosis are frequent complications, and in PV and ET, they are the most common cause of morbidity and mortality.1,3

For this reason, a core aspect of MPN management is the reduction of thrombotic risk. Given the important impact of cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs), including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), smoking status, and obesity, on thrombosis in the general population, addressing these CVRFs is also important in MPNs. However, more data are needed on the relative contribution of individual CVRFs to the morbidity and mortality of patients with MPNs. It is unclear how CVRFs affect other outcomes in patients with MPNs, including progression to MF or acute leukemia, and whether CVRFs affect the MPN population differently than the general population. For this reason, we conducted, to our knowledge, the largest real-world retrospective cohort analysis of 1005 patients with MPNs to evaluate the impact of CVRFs on patient outcomes. We also evaluated whether CVRFs have a differing association with outcomes in patients with MPNs compared with a non-MPN control population.

Methods

Study design and sample

This is a retrospective cohort study of 1005 patients with a World Health Organization 2016 diagnosis of an MPN (PV, ET, MF, prefibrotic MF, or MPN not otherwise specified) included in the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) Hematologic Malignancy Data Repository (HMDR) from 2014 to 2023. Patients are included in the HMDR if they underwent a custom next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel targeting 95 genes recurrently mutated in myeloid and lymphoid malignancies.4 A total of 1543 participants from the DFCI HMDR with no pathogenic mutations and no hematologic malignancy diagnosed on follow-up were used as a non-MPN control group. Follow-ups can occur outside the care of a hematologist/oncologist (ie, such as a primary care or other medical specialty setting), as long as medical encounters occurred with an institution linked to the reference center’s electronic medical record. This study was approved by the Dana Farber Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board and included waiver of informed consent for retrospective chart review. Study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient variables and outcomes

CVRFs were identified in the electronic medical record through International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9/10 diagnoses of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, DM2, current smoking status, and a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2. CVRFs must have been present before or within 1 year of MPN diagnosis. Given the significant missing data for BMI within 1 year of MPN diagnosis (n = 529), BMI data closest to MPN diagnosis were also used. In patients with multiple BMI time points available (n = 281), 96% had BMIs within a 20% range at all time points, and the mean percent BMI change was –0.7%. Arterial thrombosis was defined as myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, transient ischemic attack, stroke, or peripheral artery disease; venous thrombosis was defined as pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, cerebral vein thrombosis, or splanchnic vein thrombosis. Time to thrombosis was defined as the time from MPN diagnosis to a thrombotic event; thrombotic events that occurred >2 years before MPN diagnosis were considered prior thrombotic events.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographics are described with summary statistics. We evaluated clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with MPNs with or without a CVRF. Differences were tested using Wilcoxon rank-sum (or Kruskal-Wallis for ≥3 groups) or Fisher exact tests, respectively. The primary outcome was overall survival (OS). Secondary outcomes included survival free from death and venous, arterial, and all thrombosis; leukemia; and MF. Time-to-event end points were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated using Greenwood method to estimate variance. Death as a competing risk was used for all time-to-event analyses. Median follow-up was calculated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. Univariable and multivariable Cox regressions were summarized with hazard ratios (HRs), 95% CIs, and Wald P values. Multivariable models were adjusted for variables significant in univariate analysis, in addition to established risk factors for OS and thrombosis. Missing variables were excluded from univariable and multivariable analysis. Cumulative incidence outcomes were modeled with death as a competing risk, and distributions were compared using Gray test.

A subcohort of controls was age- and sex-matched with patients with MPNs. Patients were matched 1:1 without replacement on sex and continuous age using the method of nearest neighbors on propensity scores. Multivariable Cox regression analysis, including an interaction term between disease status and the presence of a CVRF, was used to investigate whether the presence of an MPN would moderate the impact of a CVRF on OS and arterial/venous thrombosis. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.2 (2023-10-31).

Results

CVRFs in patients with MPNs

Of the 1005 patients with MPNs, 415 had ET, 313 had PV, 28 had pre-MF, 215 had MF, and 34 had MPN not otherwise specified. Up to 34% of patients with MPNs had at least 1 CVRF, with patients with MF more likely to have a CVRF than those with ET or PV (36% in ET, 33% in PV, and 46% in MF; P < .001). Of the CVRFs in all patients with MPNs, 21% had hypertension (13% in ET, 21% in PV, and 31% in MF), 16% had hyperlipidemia (15% in ET, 15% in PV, and 22% in MF), 12% had BMI ≥30 (12% in ET, 13% in PV, and 11% in MF), 4% were current smokers at the time of diagnosis (4% in ET, 5% in PV, and 4% in MF), and 3% had DM2 (3% in ET, 3% in PV, and 4% in MF). Four percent and 9% of patients with MPNs had a prior history of venous or arterial thrombosis, respectively (4% and 8% in ET, 4% and 10% in PV, and 5% and 9% in MF).

Table 1 describes clinical and molecular characteristics of PV, ET, MF, and all patients with MPNs with ≥1 CVRF compared with those with no CVRFs. Patients with MPNs with ≥1 CVRF were more likely male (54% vs 45%; P < .001), older at MPN diagnosis (median age, 65 vs 56 years; P < .001), and more likely to have MF (29% vs 17%; P < .001). Race was not significantly different (P = .11), although the majority of patients in this cohort were White. Median follow-up from MPN diagnosis was significantly longer in patients without a CVRF (8.3 vs 3.1 years; P < .001). These results were similar when looking at ET, PV, and MF. Driver mutation status was not significantly different in PV, ET, MF, and all patients with MPNs with or without a CVRF. However, JAK2 variant allele frequency (VAF) was lower in patients with MPNs with a CVRF (37% vs 50.63%; P < .001), which was primarily driven by JAK2 VAF differences in patients with PV. We found no differences in VAF for CALR- or MPL-mutated patients. There were also no differences in the presence or the number of nonphenotypic driver mutations between patients with MPNs with or without a CVRF, although patients with ET were less likely to have a nonphenotypic driver mutation if they had a CVRF. Patients with MPNs with ≥1 CVRF were more likely to have a prior history of arterial (16% vs 5%; P < .001) and venous (6% vs 3%; P = .030) thrombosis.

Clinical characteristics of patients with MPNs with or without a CVRF, as divided by disease subtype

| . | All MPNs . | ET . | PV . | MF . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CVRF (n = 663) . | ≥1 CVRF (n = 342) . | No CVRF (n = 303) . | ≥1 CVRF (n = 112) . | No CVRF (n = 209) . | ≥1 CVRF (n = 104) . | No CVRF (n = 115) . | ≥1 CVRF (n = 100) . | |

| Female, n (%) | 365 (55) | 157 (46) | 184 (61) | 60 (54) | 112 (54) | 46 (44) | 53 (46) | 34 (34) |

| Age at MPN diagnosis, median (range), y | 56 (9-91) | 65 (18-96) | 53 (9-87) | 61 (18-96) | 54 (18-91) | 64 (21-94) | 63 (21-86) | 68 (31-84) |

| First MPN diagnosis, n (%) | ||||||||

| ET | 303 (46) | 112 (33) | ||||||

| PV | 209 (32) | 104 (30) | ||||||

| Pre-MF | 15 (2) | 13 (4) | ||||||

| MF | 115 (17) | 100 (29) | ||||||

| MPN NOS | 21 (3) | 13 (4) | ||||||

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| White | 609 (92) | 304 (89) | 278 (92) | 95 (85) | 192 (92) | 96 (92) | 106 (92) | 89 (89) |

| Black | 17 (3) | 14 (4) | 9 (3) | 7 (6) | 4 (2) | 4 (4) | 4 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Asian | 21 (3) | 8 (2) | 10 (3) | 5 (4) | 7 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Unknown | 16 (2) | 16 (5) | 6 (2) | 5 (4) | 6 (3) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 6 (6) |

| Median follow-up, y | 8.3 | 3.1 | 8.9 | 4.3 | 11.3 | 3.5 | 4 | 2.2 |

| Driver mutation | ||||||||

| JAK2 | 435 (66)∗ | 228 (67) | 166 (55)∗ | 56 (50) | 192 (92)∗ | 96 (92) | 59 (51)∗ | 61 (61) |

| CALR | 119 (18) | 49 (14) | 89 (29) | 28 (25) | 23 (20) | 20 (20) | ||

| MPL | 32 (5)∗ | 20 (6) | 14 (5)∗ | 10 (9) | 1 (0)∗ | 15 (13)∗ | 8 (8) | |

| Triple negative | 81 (12) | 45 (13) | 36 (12) | 18 (16) | 17 (8) | 8 (8) | 19 (17) | 11 (11) |

| VAF, median (range) | ||||||||

| JAK2 | 50.63 (0.45-99.41) | 37.61 (1.03-97.73) | 30.17 (0.45-96.69) | 24.39 (1.39-91.24) | 70.27 (1.98-99.41) | 40.31 (1.03-96.73) | 51.83 (1.65-97.62) | 44.16 (2.81-95.71) |

| CALR | 34.26 (2.52-89.39) | 34.35 (9.01-80.65) | 33.33 (2.52-61.22) | 31.20 (9.01-57.75) | 39.29 (22.78-82.35) | 36.37 (23.12-80.65) | ||

| MPL | 43.52 (2.75-93.06) | 38.09 (3.27-79.38) | 42.48 (2.75-93.06) | 18.05 (3.27-69.19) | 3.93 (3.93-3.93) | 53.23 (32.27-90.83) | 45.66 (32.30-75.37) | |

| Nondriver mutations | ||||||||

| Yes | 354 (53) | 187 (55) | 139 (46) | 35 (31) | 102 (49) | 60 (58) | 81 (70) | 75 (75) |

| Median (range) | 1 (0-6) | 1 (0-7) | 0 (0-6) | 0 (0-5) | 0 (0-6) | 1 (0-5) | 1 (0-6) | 1 (0-7) |

| BMI, median (range) | 24.82 (15.48-52.42) | 27.50 (15.33-58.10) | 24.64 (16.45-47.93) | 27.35 (15.33-58.10) | 24.94 (15.48-41.04) | 26.45 (20.04-47.37) | 24.41 (17.52-40.19) | 27.75 (18.68-54.91) |

| History of venous thrombosis, n (%) | 21 (3) | 21 (6) | 8 (3) | 9 (8) | 7 (3) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 6 (6) |

| History of arterial thrombosis, n (%) | 34 (5) | 56 (16) | 13 (4) | 18 (16) | 12 (6) | 19 (17) | 6 (5) | 13 (13) |

| . | All MPNs . | ET . | PV . | MF . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CVRF (n = 663) . | ≥1 CVRF (n = 342) . | No CVRF (n = 303) . | ≥1 CVRF (n = 112) . | No CVRF (n = 209) . | ≥1 CVRF (n = 104) . | No CVRF (n = 115) . | ≥1 CVRF (n = 100) . | |

| Female, n (%) | 365 (55) | 157 (46) | 184 (61) | 60 (54) | 112 (54) | 46 (44) | 53 (46) | 34 (34) |

| Age at MPN diagnosis, median (range), y | 56 (9-91) | 65 (18-96) | 53 (9-87) | 61 (18-96) | 54 (18-91) | 64 (21-94) | 63 (21-86) | 68 (31-84) |

| First MPN diagnosis, n (%) | ||||||||

| ET | 303 (46) | 112 (33) | ||||||

| PV | 209 (32) | 104 (30) | ||||||

| Pre-MF | 15 (2) | 13 (4) | ||||||

| MF | 115 (17) | 100 (29) | ||||||

| MPN NOS | 21 (3) | 13 (4) | ||||||

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| White | 609 (92) | 304 (89) | 278 (92) | 95 (85) | 192 (92) | 96 (92) | 106 (92) | 89 (89) |

| Black | 17 (3) | 14 (4) | 9 (3) | 7 (6) | 4 (2) | 4 (4) | 4 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Asian | 21 (3) | 8 (2) | 10 (3) | 5 (4) | 7 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Unknown | 16 (2) | 16 (5) | 6 (2) | 5 (4) | 6 (3) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 6 (6) |

| Median follow-up, y | 8.3 | 3.1 | 8.9 | 4.3 | 11.3 | 3.5 | 4 | 2.2 |

| Driver mutation | ||||||||

| JAK2 | 435 (66)∗ | 228 (67) | 166 (55)∗ | 56 (50) | 192 (92)∗ | 96 (92) | 59 (51)∗ | 61 (61) |

| CALR | 119 (18) | 49 (14) | 89 (29) | 28 (25) | 23 (20) | 20 (20) | ||

| MPL | 32 (5)∗ | 20 (6) | 14 (5)∗ | 10 (9) | 1 (0)∗ | 15 (13)∗ | 8 (8) | |

| Triple negative | 81 (12) | 45 (13) | 36 (12) | 18 (16) | 17 (8) | 8 (8) | 19 (17) | 11 (11) |

| VAF, median (range) | ||||||||

| JAK2 | 50.63 (0.45-99.41) | 37.61 (1.03-97.73) | 30.17 (0.45-96.69) | 24.39 (1.39-91.24) | 70.27 (1.98-99.41) | 40.31 (1.03-96.73) | 51.83 (1.65-97.62) | 44.16 (2.81-95.71) |

| CALR | 34.26 (2.52-89.39) | 34.35 (9.01-80.65) | 33.33 (2.52-61.22) | 31.20 (9.01-57.75) | 39.29 (22.78-82.35) | 36.37 (23.12-80.65) | ||

| MPL | 43.52 (2.75-93.06) | 38.09 (3.27-79.38) | 42.48 (2.75-93.06) | 18.05 (3.27-69.19) | 3.93 (3.93-3.93) | 53.23 (32.27-90.83) | 45.66 (32.30-75.37) | |

| Nondriver mutations | ||||||||

| Yes | 354 (53) | 187 (55) | 139 (46) | 35 (31) | 102 (49) | 60 (58) | 81 (70) | 75 (75) |

| Median (range) | 1 (0-6) | 1 (0-7) | 0 (0-6) | 0 (0-5) | 0 (0-6) | 1 (0-5) | 1 (0-6) | 1 (0-7) |

| BMI, median (range) | 24.82 (15.48-52.42) | 27.50 (15.33-58.10) | 24.64 (16.45-47.93) | 27.35 (15.33-58.10) | 24.94 (15.48-41.04) | 26.45 (20.04-47.37) | 24.41 (17.52-40.19) | 27.75 (18.68-54.91) |

| History of venous thrombosis, n (%) | 21 (3) | 21 (6) | 8 (3) | 9 (8) | 7 (3) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 6 (6) |

| History of arterial thrombosis, n (%) | 34 (5) | 56 (16) | 13 (4) | 18 (16) | 12 (6) | 19 (17) | 6 (5) | 13 (13) |

Boldface type indicates significant differences (P < .05).

NOS, not otherwise specified.

Four patients had a simultaneous mutation in JAK2 and MPL.

Association of CVRFs on MPN outcomes

We next evaluated the association of having ≥1 CVRF on patient outcomes (Figure 1). Patients with MPNs with ≥1 CVRF had worse OS than patients without a CVRF (HR, 2.52; 95% CI, 1.9-3.35). Patients with MPNs with ≥1 CVRF had worsened thrombosis-free survival (HR, 3.05; 95% CI, 2.38-3.92), including both arterial (HR, 4.43; 95% CI, 3.26-6.01) and venous thrombosis–free survival (HR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.16-2.46), although the difference was more pronounced for arterial thrombosis. We also found worsening OS and thrombosis-free survival in patients with MPNs with multiple CVRFs compared with those with only 1 CVRF (supplemental Figure 1). Detailed information on the types of arterial and venous thrombosis occurring in patients with MPNs are included in supplemental Table 1. However, the presence of ≥1 CVRF did not affect MF-free (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.53-1.28) or leukemia-free survival (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.7-2.13; supplemental Figure 2).

Outcomes in all MPN patients with or without a cardiovascular risk factor. The graphs show OS (A), thrombosis-free survival (B-D), MF-free survival (E), and leukemia-free survival (F) in patients with MPNs with or without a CVRF. NR, not reached.

Outcomes in all MPN patients with or without a cardiovascular risk factor. The graphs show OS (A), thrombosis-free survival (B-D), MF-free survival (E), and leukemia-free survival (F) in patients with MPNs with or without a CVRF. NR, not reached.

Impact of CVRFs within MPN subtypes

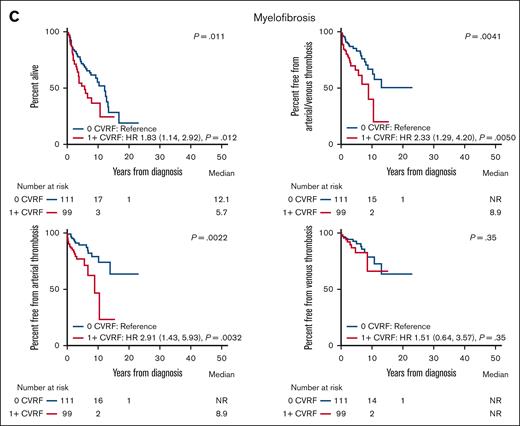

The presence of a CVRF was also associated with worse outcomes in ET, PV, and MF (Figure 2). Patients with ET with ≥1 CVRF had worse OS (HR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.29-3.75), arterial thrombosis (HR, 3.90; 95% CI, 2.40-6.35), and combined arterial or venous thrombosis (HR, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.95-4.48) than patients with ET without any CVRF. The presence of ≥1 CVRF was not associated with worse survival from venous thrombosis (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 0.71-2.98), MF (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.58-1.89), or leukemia (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.24-2.70) in patients with ET (Figure 2; supplemental Figure 2). Similarly, patients with PV with ≥1 CVRF had worse OS (HR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.12-3.64), arterial thrombosis (HR, 5.72; 95% CI, 3.39-9.63), venous thrombosis (HR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.09-3.30), and combined arterial or venous thrombosis (HR, 3.33; 95% CI, 2.23-4.98). There was no association between the presence of ≥1 CVRF and MF-free survival (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.35-1.37) or leukemia-free survival (HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 0.67-4.71) in patients with PV (supplemental Figure 2). Within patients with MF, the presence of ≥1 CVRF also predicted worse OS (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.14-2.92), arterial thrombosis (HR, 2.91; 95% CI, 1.43-5.93), and combined arterial or venous thrombosis (HR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.29-4.20). The presence of ≥1 CVRF was not associated with worsened survival from venous thrombosis (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 0.64-3.57) or leukemia (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.32-2.05) in patients with MF (Figure 2; supplemental Figure 2). We similarly found worsened OS and thrombosis-free survival in patients with ET, PV, and MF with multiple CVRFs compared with those with 1 CVRF (supplemental Figure 1).

Overall and thrombosis-free survival in MPN subtypes with or without a cardiovascular risk factor. The graphs show OS and thrombosis-free survival in patients with ET (A), PV (B), and MF (C) with or without a CVRF. NR, not reached.

Overall and thrombosis-free survival in MPN subtypes with or without a cardiovascular risk factor. The graphs show OS and thrombosis-free survival in patients with ET (A), PV (B), and MF (C) with or without a CVRF. NR, not reached.

Individual CVRFs and MPN outcomes

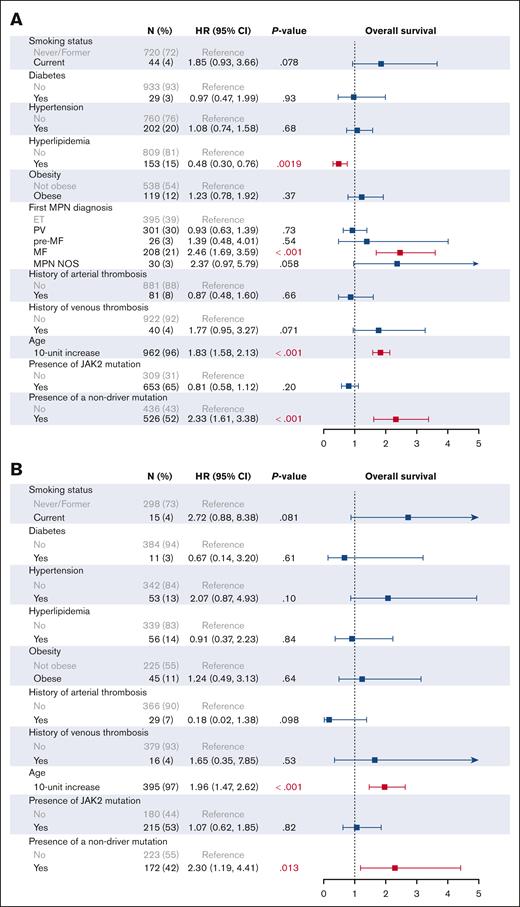

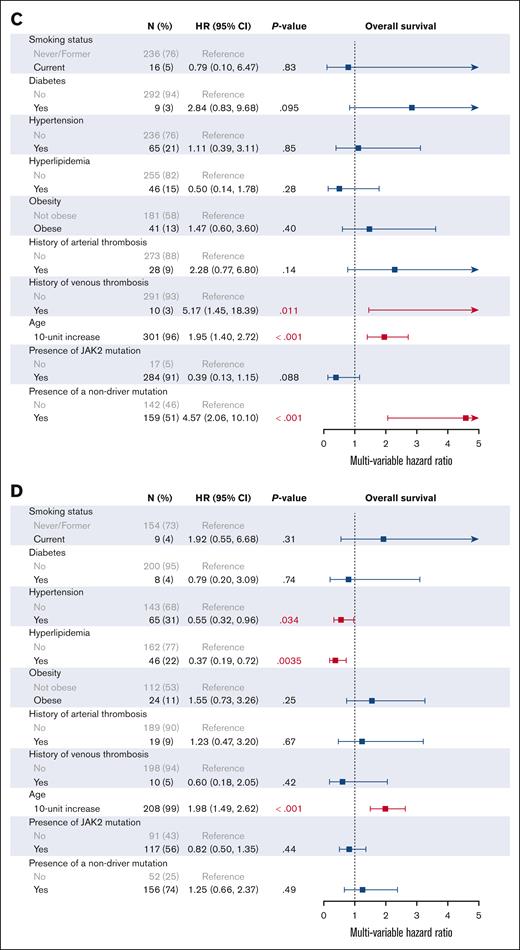

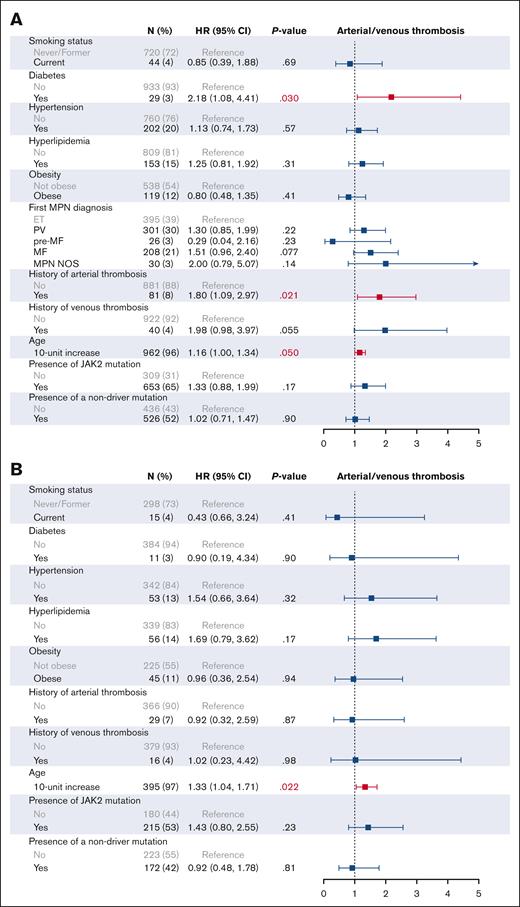

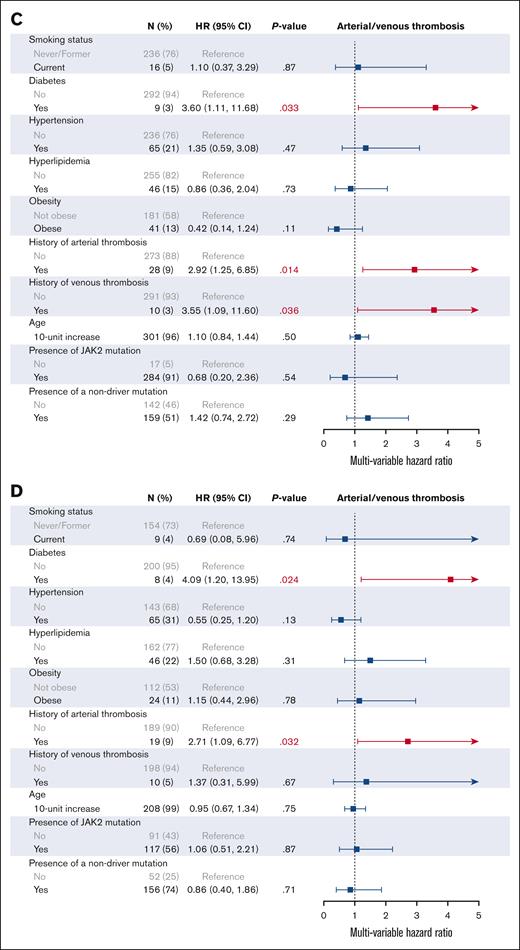

We then investigated the effect of individual CVRFs on patient outcomes on univariable (supplemental Figure 3) and multivariable analysis (Figures 3 and 4). In addition to all CVRFs, age, mutation status, MPN subtype, and prior history of arterial or venous thrombosis were included for multivariable analysis, given their known associations with thrombotic outcomes. As expected, older age (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.58-2.13), an MF diagnosis (HR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.69-3.59), and the presence of nonphenotypic driver mutations (HR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.61-3.38) were associated with worse OS on multivariable analysis. In all patients with MPNs, no CVRFs were associated with worsened OS, and interestingly, we found that hyperlipidemia improved OS (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.30-0.76). Similarly, no CVRFs were associated with worsened OS when looking at patients with ET, PV, and MF individually; however, hypertension and hyperlipidemia were associated with improved OS in patients with MF (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.32-0.96; and HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.19-0.72, respectively). When looking at arterial and venous thrombosis, DM2 was the only significant CVRF on multivariable analysis in all patients with MPNs (HR, 2.68; 95% CI, 1.23-5.83). DM2 also remained adversely associated with thrombosis in patients with PV (HR, 3.60; 95% CI, 1.11-11.68) and MF (HR, 4.09; 95% CI, 1.20-13.95) but not in ET (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.19-4.34).

Multivariable analysis of cardiovascular risk factors associated with overall survival. Multivariable analysis of CVRFs associated with OS in all MPNs (A), ET (B), PV (C), and MF (D) is shown.

Multivariable analysis of cardiovascular risk factors associated with overall survival. Multivariable analysis of CVRFs associated with OS in all MPNs (A), ET (B), PV (C), and MF (D) is shown.

Multivariable analysis of CVRFs associated with arterial and venous thrombosis. (A) All MPNs; (B) ET; (C) PV; (D) MF.

Multivariable analysis of CVRFs associated with arterial and venous thrombosis. (A) All MPNs; (B) ET; (C) PV; (D) MF.

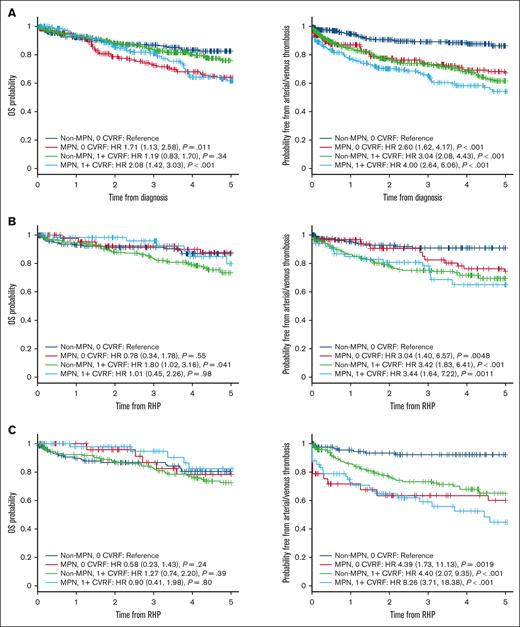

Impact of CVRFs in patients with MPNs compared with non-MPN controls

Because CVRFs are known to negatively affect outcomes in the general population, we evaluated whether the harmful associations of CVRFs differentially affected the MPN population. We used a matched non-MPN control group of 1543 patients seen at DFCI who had no evidence for pathogenic mutations on NGS testing and were never diagnosed with a hematologic malignancy on follow-up. We restricted the analysis to 5 years of follow-up given the longer follow-up of patients with MPNs than controls (5.9 vs 2.7 years; P < .001).

Patients with MPNs had lower BMI (25.70 vs 26.85; P < .001) and were less likely to be obese (56% vs 61%; P < .001) than controls (n = 985); patients with MPNs were also less likely to be never smokers (44% vs 51%; P < .001) and less likely to have DM2 (3% vs 8%; P < .001), hyperlipidemia (16% vs 21%; P = .0076), and hypertension (21% vs 31%; P < .001). Patients with MPNs also had fewer prior arterial thrombosis (9% vs 16%; P < .001) and a trend toward fewer prior venous thrombosis (4% vs 6%; P = .053; Table 2). We also found lower prevalence rates of hypertension (13% vs 27%; P < .001), DM2 (3% vs 7%; P = .012), and prior arterial thrombosis (7% vs 12%; P = .023) in patients with ET; lower prevalence rates of obesity (13% vs 25%; P = .015), hypertension (22% vs 32%; P = .0048), and DM2 (3% vs 8%; P = .021) in patients with PV; and lower prevalence rates of hypertension (31% vs 42%; P = .026), DM2 (4% vs 10%; P = .03), and prior arterial thrombosis (9% vs 23%; P < .001) in patients with MF (supplemental Table 2). However, despite the lower prevalence of many CVRFs, patients with MPNs had worse 5-year OS (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.31-2.26) and worse 5-year survival free from arterial or venous thrombosis (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.19-1.98).

Clinical characteristics of age- and sex-matched patients with MPNs and non-MPN controls

| . | MPN (n = 983) . | Non-MPN (n = 983) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 511 (52) | 511 (52) | >.99 |

| Age at diagnosis,∗ median (range), y | 58 (9-96) | 58 (17-95) | >.99 |

| Median follow-up, y | 5.9 | 2.7 | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 893 (91) | 100 (10) | <.001 |

| Black | 30 (3) | 8 (1) | |

| Asian | 28 (3) | 5 (1) | |

| Other/unknown | 32 (3) | 870 (89) | |

| BMI | |||

| Median (range) | 25.7 (15.33-58.10) | 26.85 (12.76-55.28) | <.001 |

| ≥30, n (%) | 122 (12) | 266 (27) | <.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 207 (21) | 16 (6) | |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 159 (16) | 44 (15) | |

| DM2, n (%) | 30 (3) | ||

| Smoking status | <.001 | ||

| Never smoker | 434 (44) | 504 (51) | |

| Former smoker | 299 (30) | 262 (27) | |

| Current smoker | 44 (4) | 93 (9) | |

| Unknown | 206 (30) | 124 (13) | |

| History of venous thrombosis, n (%) | 41 (4) | 61 (6) | .053 |

| History of arterial thrombosis, n (%) | 84 (9) | 153 (16) | <.001 |

| . | MPN (n = 983) . | Non-MPN (n = 983) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 511 (52) | 511 (52) | >.99 |

| Age at diagnosis,∗ median (range), y | 58 (9-96) | 58 (17-95) | >.99 |

| Median follow-up, y | 5.9 | 2.7 | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 893 (91) | 100 (10) | <.001 |

| Black | 30 (3) | 8 (1) | |

| Asian | 28 (3) | 5 (1) | |

| Other/unknown | 32 (3) | 870 (89) | |

| BMI | |||

| Median (range) | 25.7 (15.33-58.10) | 26.85 (12.76-55.28) | <.001 |

| ≥30, n (%) | 122 (12) | 266 (27) | <.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 207 (21) | 16 (6) | |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 159 (16) | 44 (15) | |

| DM2, n (%) | 30 (3) | ||

| Smoking status | <.001 | ||

| Never smoker | 434 (44) | 504 (51) | |

| Former smoker | 299 (30) | 262 (27) | |

| Current smoker | 44 (4) | 93 (9) | |

| Unknown | 206 (30) | 124 (13) | |

| History of venous thrombosis, n (%) | 41 (4) | 61 (6) | .053 |

| History of arterial thrombosis, n (%) | 84 (9) | 153 (16) | <.001 |

Age at diagnosis for non-MPN controls is age at entry into database.

CVRFs were not associated with worse 5-year OS in controls (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.83-1.70), although control patients with ≥1 CVRF had more thrombotic events at 5 years (HR, 3.0; 95% CI, 2.08-4.43). We found a significant interaction between an MPN diagnosis and the presence of a CVRF for arterial or venous thrombosis (P = .012; supplemental Table 3). The presence of a CVRF had half the HR of arterial or venous thrombosis in patients with MPNs compared with controls (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.36-0.86). Patients with MPNs without a CVRF had similar risk of a thrombotic event as controls with a CVRF, with further decline in thrombosis-free survival when a CVRF is present (Figure 5). Patients with ET had thrombotic outcomes that tracked more closely with controls (Figure 5), although a significant negative interaction remained (HR, 0.35; P = .019), indicating that a CVRF has less of an impact on thrombotic risk in patients with ET compared with controls (supplemental Table 3). In contrast, thrombotic outcomes were worse in all patients with PV, including when comparing patients with PV with no CVRF with controls with a CVRF (Figure 5). There were no significant interactions between cohorts and the presence of a CVRF for thrombosis in patients with PV and MF, nor for OS in all MPNs (supplemental Table 3).

Comparison of outcomes in MPN patients and non-MPN controls stratified by cardiovascular risk factors. The graphs show OS and thrombosis-free survival in patients with MPNs (A), ET (B), PV (C), and MF and non-MPN controls (D), stratified by presence of at least 1 CVRF. RHP, Rapid Heme Panel.

Comparison of outcomes in MPN patients and non-MPN controls stratified by cardiovascular risk factors. The graphs show OS and thrombosis-free survival in patients with MPNs (A), ET (B), PV (C), and MF and non-MPN controls (D), stratified by presence of at least 1 CVRF. RHP, Rapid Heme Panel.

Discussion

This is, to our knowledge, the largest retrospective analysis of a real-world population evaluating the impact of CVRFs in patients with MPNs. CVRFs occurred in 34% of the MPN cohort (n = 1005), with prevalence rates of 21%, 16%, 12%, 4%, and 3% for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, current smoking status, and DM2, respectively. When looking at ET, PV, and MF specifically, we found that patients with MF were more likely to have a CVRF than those with ET and PV, which was primarily driven by increased rates of hypertension and hyperlipidemia. The presence of ≥1 CVRF was associated with worse OS and thrombosis-free survival among patients with ET, PV, and MF and all patients with MPNs, with no associations with progression to MF or acute leukemia. The risk of arterial thrombosis with a CVRF was particularly pronounced in PV, in which the presence of ≥1 CVRF predicted nearly a sixfold increased risk of subsequent arterial thromboses. Among the CVRFs examined, only DM2 was adversely associated with increased thrombotic risk in all patients with MPNs; this remained true in patients with PV and MF but not in those with ET. We also found that CVRFs affected thrombotic risk differently in patients with MPNs compared with non-MPN controls; although when looking at individual disease groups, a significant interaction between MPN diagnosis and the presence of a CVRF occurred only in ET and not PV or MF.

Prevalence rates for CVRFs in patients with MPNs vary widely due to differing definitions of CVRFs, heterogeneity of time points at which CVRFs are reported, inherent limitations of retrospectively collected data, and differences in socioeconomic and geographic variables. In ET, the prevalence rates of CVRFs are ∼60% for hypertension, 20% for hyperlipidemia, 15% for DM2, 10% for obesity, and 10% for smoking exposure5,6; for PV, the prevalence rates are similar and include up to 70% for hypertension, 40% for hyperlipidemia, 15% for DM2, 10% for obesity, and 15% for current smoking.7-9 In MF, the prevalence rates of up to 20% for hypertension, 10% for hyperlipidemia, 30% for obesity, and 30% for current smoking have been reported.10-12 Our prevalence rates appear lower than what is reported in the literature, and we found higher prevalence rates of CVRFs in patients with MF. This may be related to the fact that patients with MF are more likely to be older than patients with ET or PV, but we cannot rule out that CVRFs contribute to an inflammatory milieu that may then predispose to fibrotic progression. Overall, CVRF prevalence rates in both MPN and non-MPN cohorts appear lower than what is reported in the general adult US population,13 which may reflect referral biases at our institution. However, even when comparing our MPN and non-MPN cohorts, we did not find evidence for significantly increased prevalence of CVRFs, despite the fact that patients with MPNs still had worse outcomes overall. This suggests either a greater detriment to outcomes conferred by a CVRF or worse outcomes in patients with MPNs without a CVRF. Our analysis suggests the latter is true.

Within patients with ET, PV, and MF and all patients with MPNs, we found that patients with ≥1 CVRF were more likely to be male and older. We did note that patients without a CVRF had longer follow-up than patients with a CVRF, which may be due to a younger age at diagnosis, which allows for longer follow-up. Patients with MPNs with a CVRF had lower JAK2 VAFs, even though patients with MPNs with a CVRF also tended to be older, and this was primarily driven by patients with PV. This is a novel finding that should be explored more fully to investigate how the inflammatory effects of a patient’s comorbidities affect the clonal expansion of JAK2-mutated stem cells. The distribution of JAK2-, CALR-, and MPL-mutated patients was similar in patients with ET, PV, and MF and all patients with MPNs with or without a CVRF.

Patients with ET, PV, and MF and all patients with MPNs with ≥1 CVRF have overall worse outcomes than those without CVRFs, with increased risk of death and arterial, venous, and all-cause thrombosis, and the presence of multiple CVRFs also had an additive adverse effect on outcomes. The International Prognostic Score of Thrombosis in Essential Thrombocythemia (IPSET)-thrombosis score in ET established CVRFs of arterial hypertension, DM2, and smoking as independent risk factors for thrombosis, although subsequent revision of the IPSET-thrombosis found that these CVRFs do not significantly distinguish thrombotic risk in low- and high-risk ET, leading to the omission of CVRFs as a risk factor in the revised (R)-IPSET scoring system.14,15 We, however, found that a CVRF was associated with worse OS and thrombosis-free survival in ET, with CVRFs primarily influencing arterial rather than venous thrombotic risk. Within patients with PV, CVRFs including arterial hypertension, DM2, and smoking have been associated with increased thrombosis, although most commonly used thrombotic-risk classification systems do not formally include CVRFs for risk stratification.8,9,16,17 This perhaps needs to be revisited, because the hazard of a CVRF was particularly pronounced in PV, in addition to increasing risk of death and venous thrombosis. CVRFs have had a less clear impact on outcomes in MF.12 Our analysis, however, indicates that CVRFs similarly are associated with worse survival and thrombotic risk in patients with MF as well. Of note, we did not find that CVRFs predicted subsequent development of leukemia or MF transformation, suggesting that the impact of CVRFs on OS is largely mediated by causes of death other than progression.

We also evaluated the impact of individual CVRFs on outcomes. Among CVRFs evaluated in this analysis, only DM2 emerged as a clear risk factor for arterial or venous thrombosis. We did not find an association with adverse outcomes in current smokers, although other studies have found increased thrombotic risk when looking at any smoking exposure in ET.18,19 Interestingly, we found that hyperlipidemia was associated with improved OS in all patients with MPNs; and specifically within MF, both hyperlipidemia and hypertension also had better OS. It is possible that hypertension in MF is associated with a more proliferative phenotype, and the presence of hypolipidemia has been previously found as an adverse prognostic marker in patients with MF.20 Hyperlipidemia may also be an indicator of ruxolitinib use, which is known to increase cholesterol levels and improve MF outcomes. These findings, however, would need to be validated further. We found no relationship between BMI and obesity with adverse outcomes. The relationship between increased weight and MPN outcomes is also complex given that weight loss and cachexia are also negative prognostic indicators, particularly in MF. Indeed, some studies have noted a protective effect of obesity, with decreased rates of fibrotic progression in patients with PV with a BMI >25.21 In contrast, obesity has been linked to increased incidence of ET development.22 Targeting a specific weight is likely less important compared with practicing healthy lifestyle patterns, maintaining optimal body composition, and treating other cardiovascular comorbidities. Our analysis is limited by missing BMI data, and it is possible that a significant relationship would have been observed with complete data, particularly if patients with missing data were biased in some way.

Although our results demonstrate unequivocally the poorer association of CVRFs with outcomes in patients with ET, PV, and MF and all patients with MPNs, we found CVRFs have less of an impact on thrombosis compared with a non-MPN population. The presence of a CVRF had approximately half the HR of thrombosis in patients with MPNs compared with non-MPN controls, with similar thrombosis-free survival seen in patients with MPNs with no CVRF and non-MPN controls with a CVRF. This negative interaction between MPN diagnosis and CVRF was also seen when looking at patients with ET separately, suggesting that the lesser impact of a CVRF on thrombosis in ET is related to the greater baseline risk of thrombosis, even in patients with ET without a CVRF. We found no interactions in patients with PV and MF. Indeed, all patients with PV, regardless of the presence of CVRFs, had markedly increased risk of thrombosis at the start of diagnosis, compared with controls. In patients with MF, we may have been underpowered to find a statistically significant interaction between an MF diagnosis and the presence of a CVRF, although the thrombosis-free survival curves appear more similar to that of ET than PV. Overall, these results suggest that the poorer thrombotic outcomes seen in patients with MPNs is due to the higher baseline risk of thrombosis even in patients without a CVRF, rather than a greater impact on thrombosis from a preexisting CVRF. This underscores the importance of other aspects of thrombotic risk management in patients with MPNs besides addressing CVRFs, such as blood count optimization and a healthy lifestyle.

Our study has several limitations. We relied on ICD-9/10 codes, which are susceptible to inaccurate documentation. The use of ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes may also lead to underrepresentation of harder-to-diagnose MPN subtypes such as prefibrotic MF. Because this is a retrospective analysis of CVRFs found before or during MPN diagnosis, we cannot definitively evaluate how modification of these risk factors affects outcomes. Although more difficult to undertake, prospective studies and interventional studies on CVRF reduction (including but not limited to studies evaluating lifestyle modifications) are therefore needed in this population. Although the control cohort had no pathogenic mutations on NGS suggestive of a hematologic malignancy and no subsequent diagnoses observed on follow-up, we cannot guarantee an absence of an underlying blood disorder when they were seen. For this reason, we refer to this group as non-MPN controls rather than healthy controls. However, we chose to include these patients as comparators because they likely have more similar biases than controls taken from another database, as underscored by our initial findings that both cohorts had lower-than-expected prevalence of CVRFs compared with that of the general population.

In conclusion, we found that CVRFs are common in patients with MPNs and are associated with worse OS and thrombosis, although not with progression to MF or leukemia. DM2 in particular emerged as a risk factor for subsequent thrombosis. The hazard of CVRFs for thrombosis is decreased in patients with MPNs compared with non-MPN patients, emphasizing the overall higher baseline thrombotic risk inherent to MPN disease rather than a greater effect on thrombosis from a CVRF. Our results emphasize that optimization of CVRFs remains an essential part of MPN care, although thrombotic risk remains elevated even in the absence of such risk factors.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the team supporting the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Hematologic Malignancy Data Repository for assistance with this study.

Authorship

Contribution: J.H. and G.H. designed the study; J.H., L.D.W., M.W., A.E.M., and C.K. collected data; D.J.D., R.C.L., M.S., and M.L. curated data for the Hematologic Malignancy Data Repository database; J.H., R.R., and O.L. analyzed data; A.E.-J. and C.M.D.-C. interpreted data; J.H. wrote the initial manuscript; and all authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.H. reports consultancy fees from PharmaEssentia and Merck. L.D.W. reports consultancy fees from AbbVie and Vertex; and membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committees in Sobi. M.S. served on the advisory board for Novartis, Kymera, Sierra Oncology, GlaxoSmithKline, Rigel, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Sobi, and Syndax; consulted for Boston Consulting and The Dedham Group; and participated in Continuing Medical Education activity for Novartis, Curis Oncology, Haymarket Media, and Clinical Care Options. D.J.D. reports honoraria from Pfizer, Incyte, Amgen, Takeda, Servier, Jazz, Kite, Blueprint, Autolus, Novartis, and Gilead; and research funding from AbbVie, Novartis, Blueprint, and GlycoMimetics. C.L. reports consultancy fees from Takeda Pharmaceuticals, bluebird bio, Qiagen, Sarepta Therapeutics, Verve Therapeutics, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals; and membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committees in bluebird bio. M.L. reports research funding from AbbVie and Novartis; and honoraria from Jazz, Pfizer, Novartis, and Kite. A.E.-J. reports consulting fees from Incyte, Tuesday Health, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline. G.H. reports research funding from Incyte and MorphoSys; membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committees in Keros, Pharmaxis, Pfizer, MorphoSys, Novartis, Protagonist, AbbVie, and BMS; and is a current holder of stock options in a privately held company in Regeneron. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Joan How, Brigham and Women's Hospital, 75 Francis St, Boston, MA 02115; email: jhow@bwh.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Joan How (jhow@bwh.harvard.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.