Key Points

Multiple mouse genes regulating bleeding and platelet traits contribute to human hemostasis.

Combined assessment of orthologous human and mouse platelet transcriptomes and proteomes reveals their roles in hemostasis.

Visual Abstract

The hemostatic process relies on platelet and coagulation activation, with additional roles of red blood cells and the vessel wall. By systematic screening of databases for gene-linked information on hemostasis, we collected phenotypic profiles of 3474 orthologous human and mouse genes regarding bleeding, arterial thrombosis, thrombophilia, platelet traits, coagulation, and erythrocytes. Comparisons showed that defects in 252 mouse genes led to increased bleeding combined with platelet dysfunction or thrombocytopenia, in addition to 150 human orthologs that are registered for familial bleeding disorders, based on panel sequencing. Additionally, 139 mouse genes contributed to arterial thrombosis without bleeding phenotype. To further investigate the role of platelets in hemostasis, we integrated multiple genome-wide RNA-sequencing transcriptomes and proteomes from healthy subjects and C57BL/6 mice. This provided reference levels for 54 790 (54 247) transcripts and 6379 (4563) proteins in human (mouse) platelets. Orthologous transcripts in human and mouse platelets correlated with R=0.75, whereas orthologous platelet proteins correlated with R=0.87. Comparison with the phenotypic analysis revealed the following: (i) overall high qualitative similarity of human and mouse platelets regarding composition and function; (ii) presence of transcripts in platelets for most of the 3474 phenotyped genes; (iii) preponderance of syndromic platelet-expressed genes; and (iv) 20-40% overlap with genes from genome-wide association studies. For 42 mouse genes, among which receptors, signaling proteins, and transcription regulators (ASXL1, ERG, GATA2, MEIS1, NFE2, and TAL1), we confirmed novel links with human platelet function or count. This interspecies comparison can serve as a valuable resource for researchers and clinicians studying the genetics of blood-borne hemostasis and thrombosis.

Introduction

Undesired bleeding or impaired hemostasis as a disorder comes with a high genetic component.1-4 In affected patients, bleeding symptoms can be highly variable, ranging from minor discomfort (petechiae and nose bleeds), as well as harmful gastrointestinal or menstrual bleeding, up to fatal brain hemorrhage and prebirth death.5-7 Although relatively rare in the adult population, bleeding problems increase in an unpredicted manner with the use of antiplatelet, anticoagulant, or certain anticancer medications.8-10 Phenotypes linked to impaired hemostasis include quantitative or qualitative dysfunctions of platelets or the coagulation system, extending to enhanced fibrinolysis, von Willebrand factor alterations, and vascular dysfunctions.11-15 Platelet production relies on well-organized hematopoiesis, transcription, and translation programs in the bone marrow, whereas platelet activation requires complex intracellular signaling pathways triggered by multiple receptors and the secretion of autocrine substances.16-18 Except for a few genome-wide association studies (GWAS) on platelet count and size,19,20 little is known of the many genes that regulate platelet functions in hemostasis.

Nucleotide sequencing efforts have yielded information on >100 genes with links to familial platelet- or coagulation-related bleeding disorders.3,6,21-23 Yet, in less than half of the patients with a suspected familial bleeding disorder, a genetic cause for (platelet) abnormalities could be identified.2,24 In 2021, a large-scale analysis of quantitative trait loci regulating blood gene expression was published, which hardly examined the role of platelets.25 Efforts to map the contribution of noncoding and regulatory RNA elements, such as superenhancers to platelet functions, were only partly successful.26,27

In mice, on the contrary, the ablation of hundreds of genes resulted in impaired megakaryocyte differentiation and platelet dysfunctions, often with a bleeding phenotype and impaired arterial thrombosis.28 In addition, bleeding symptoms have been reported for hundreds of knockout strains by mouse phenotyping consortia.29

Based on data availability, we reasoned that integration of the gene-linked information on hemostasis and platelet traits from humans and mice can provide an untapped alternative for the finding of novel genes implicated in bleeding disorders. Of additional help herein is the information from genome-wide platelet transcriptomes, based on high-depth RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analyses.27,30-32 So far, up to 14 000 protein-coding transcripts have been identified in human platelets.33 However, knowledge of platelet proteins is less complete, limited to a few thousands.34-36 Recognizing the complexity of transcriptome and proteome comparisons,37-40 we decided to integrate multiple transcriptomes and proteomes from both human and mouse platelets as a reference tool for the assessment of relevant gene products in bleeding disorders.

In this paper, we obtained platelet- and hemostasis-related phenotypic information on 3474 orthologous human and mouse genes, which was linked to a combinational analysis of platelet-expressed transcripts and proteins. The use of gene ortholog matching assessments and protein classification criteria resulted in classified information on >19 200 orthologous expressed genes. This interspecies comparison can serve as a valuable resource for researchers and clinicians studying genotype-phenotype relations in hemostasis and thrombosis.

Methods

Integration of human and mouse phenotypes with platelet transcriptomes and proteomes

Per annotated orthologous human and mouse genes (n = 3474), we classified (supplemental Table 1) and scored (supplemental Figure 1) available information on hemostasis- and platelet-related phenotypes in the broadest sense: bleeding; arterial thrombosis tendency or thrombophilia; platelet function, development, and count; coagulation; erythrocyte traits; and platelet GWAS signatures. This phenotyping effort was combined with a list of 150 reference genes linked to hemostasis (supplemental Table 2) and with multiple genome-wide transcriptomes and proteomes, obtained from human or mouse platelets. Included genes were marked as syndromic (ie, not confined to blood phenotype in human or mouse) and as GWAS-only traits (supplemental File 1). The integrated platelet transcriptomes and proteomes are available as human- and mouse-based data files (supplemental Files 2 and 3). The phenotype sources for humans and mice are provided in supplemental Files 4 and 5.

Comparing human and mouse platelet transcriptomes and proteomes

Transcripts from RNA-seq databases and proteins from mass spectrometric analyses were assigned to Ensembl primary assembly genes, as detailed in the supplement. Gene assignments as (non)protein coding, RNA genes, or pseudogenes were checked against the National Center for Biotechnology Information for humans41 and against Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) for mice.

The compared transcriptomes were derived from well-purified platelets (CD45 depleted), collected from healthy participants or adult C57BL/6 mice, as detailed in the supplement. Aligned were RNA-seq–based data sets from 5 human platelet transcriptomes (ID1-5), 1 human megakaryocyte transcriptome (MEGID1), and 5 mouse platelet transcriptomes (MID1-5). Batch effects between human platelet transcriptomes were removed by ComBat normalization (supplemental Table 3).42 Data repository sites are listed in supplemental Table 4. Similarity of data sets in terms of ribosomal depletion was verified by plotting summative expression levels and the top 50 transcripts (supplemental Figure 1A-D). Transcript levels were expressed as fragments per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped (fpkm) or reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped (rpkm), depending on the source files.43 For mouse platelets, values were obtained as rpkm or transcripts per million (tpm). Intersample fractional means were expressed as log2(i + 1).

For protein composition, we aligned bottom-up mass spectrometric data sets from 5 human platelet proteomes (PROT_ID1-5) and 5 mouse platelet proteomes (PROT_MID1-5; supplemental Table 5; repository information in supplemental Table 6). For human platelets, calibration to protein copy numbers was performed as described before,34 based on normalized spectrum abundance factors per assigned protein (supplemental Table 7).44 For mouse platelets, protein copy numbers were calculated as defined by Zeiler et al, using stable-isotope calibration with protein standards (supplemental Table 8).35 Additional mouse platelet proteomes with normalized spectral abundance factor analyses were linearly aligned using the same standards (supplemental Table 9).

Transformation to compare orthologous platelet transcripts and proteins

To define orthologous human and mouse platelet transcripts and proteins, we used a uniform pipeline according to standard Ensembl (European Bioinformatics Institute [EMBL-EBI]) gene symbol notations (Gencode v43), coupled with a protein classification scheme (supplemental Table 1). Orthologs of mouse and human genes were checked in MGI. For the interspecies comparison of transcript levels, individual data sets (ID-15, MEGID1, and MID-15) were normalized to tpm fractions, averaged per cell type, and log2(i + 1) transformed.

Gene-linked human and mouse platelet phenotypes

As detailed in supplemental Table 10, public sources (consulted in 2023-2024) for collecting gene-linked phenotypes for human genes came from the following: Genomics England; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man; Human Phenotype Ontology; Clinically Relevant Genetic Variation (ClinVar; National Center for Biotechnology Information); GWAS catalogs (EMBL-EBI); GeneCards; and PubMed. Sources for mouse genes were as follows: a literature-based analysis of hemostasis and arterial thrombosis changes of 655 gene defects, updated from the study of Baaten et al28; MGI; International Mouse Phenotyping; and PubMed. Search was for genes linked to any bleeding (embryonal, hemorrhages, bruising, and petechiae, etc), arterial thrombosis or thrombophilia, aberrant platelet count/size/crit, erythrocyte count/size, and coagulation changes.

Statistics

Pearson regression and statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 8. Two-sided P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Human and mouse genes linked to bleeding and platelet traits

To collect up-to-date information on platelet-related genes contributing to human hemostasis, we datamined public databases (supplemental Table 10) for evidence on any human hemostatic phenotype: bleeding; thrombophilia; platelet dysfunction; platelet count, morphology, and size; coagulation (including fibrinolysis); anemia; and platelet traits from GWAS. In addition, we searched for mouse gene modification effects (platelet specific or full knockouts) on bleeding or arterial thrombosis tendency, along with platelet, coagulation, and erythrocyte phenotypes. For phenotyping, we used a simple scoring system of 5-point interval variables, with negative scores for any bleeding or defect and positive scores for any prothrombotic phenotype (thrombophilia, arterial thrombosis, and increased function or count; supplemental Figure 1).

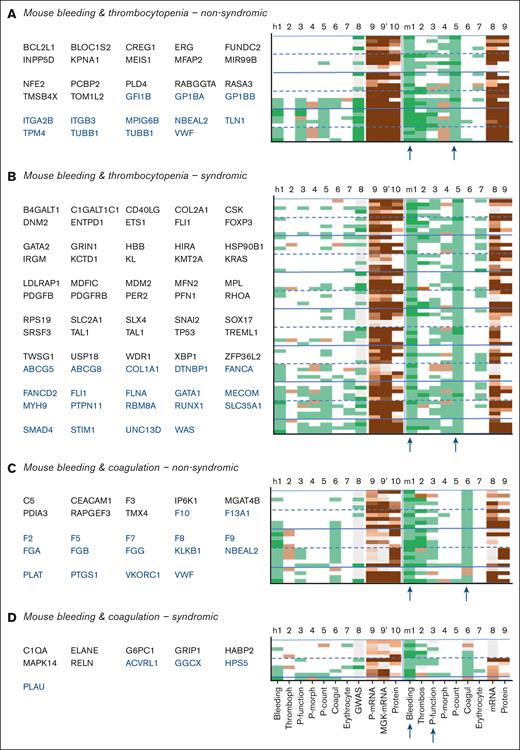

By performing cross-searches, we obtained bleeding- and platelet-related phenotype information for 3474 orthologous human and mouse genes (supplemental File 1). For most phenotypes, we identified 100 to 300 human genes and 500 to 700 mouse genes with limited overlap in the categories (Figure 1A). On the contrary, GWAS gave a platelet trait for 3463 human genes. Based on the Genomics England PanelApp (December 2024), we extracted 150 of the genes known to be linked to familial bleeding disorders (supplemental Table 2). Using a scheme for protein localization and function (Figure 1B), the reference genes with a platelet trait appeared to concentrate in several classes (Figure 1C): actin-myosin cytoskeleton (n = 8); endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus related (n = 7); membrane and protein trafficking (n = 11); membrane receptors and channels (n = 27); nuclear proteins (n = 8); protein kinases/phosphatases (n = 5); signaling proteins including GTPases (n = 13); and transcription factors (n = 10). Many of the additional genes with a coagulation phenotype were classified as secretory proteins (n = 27). To confirm the role of platelets, we decided to integrate several human and mouse platelet transcriptomes and proteomes for all of these genes.

Human and mouse genes linked to hemostasis or platelet-related phenotypes. (A) Numbers are shown of phenotyped orthologous human and mouse genes with scores for bleeding, thrombophilia (arterial thrombosis for mice), platelet function/morphology/count, coagulation (including fibrinolysis), and erythrocyte characteristics. (B) Classification scheme used for protein localization and function (classes C01-C22). (C) Human genes linked to bleeding and platelet traits per class. Colored bars indicate reference genes linked to platelet function (orange), thrombocytopenia (black) or both (brown). Gray boxes represent novel genes (names indicated); for phenotypic descriptions and data sources, see supplemental Table 13.

Human and mouse genes linked to hemostasis or platelet-related phenotypes. (A) Numbers are shown of phenotyped orthologous human and mouse genes with scores for bleeding, thrombophilia (arterial thrombosis for mice), platelet function/morphology/count, coagulation (including fibrinolysis), and erythrocyte characteristics. (B) Classification scheme used for protein localization and function (classes C01-C22). (C) Human genes linked to bleeding and platelet traits per class. Colored bars indicate reference genes linked to platelet function (orange), thrombocytopenia (black) or both (brown). Gray boxes represent novel genes (names indicated); for phenotypic descriptions and data sources, see supplemental Table 13.

Comparability of mean human and mouse platelet transcriptomes and proteomes

The integration of data sets was needed due to the unclarity of transcript-protein ratios in platelets.33,45 For the transcriptomes, we integrated 5 high-quality RNA-seq collections derived from well-purified human (healthy donors) or mouse (C57BL/6 strain) platelets. Quality checks indicated that in all data sets, protein-encoding transcripts were predominant (supplemental Figure 2). For human platelets, the combined data sets ID1-5 provided fpkm/rpkm information on 54 791 gene-linked transcripts, which were log2 transformed (Table 1). The included human megakaryocyte transcriptome, MEGID1, had a somewhat lower transcript number (n = 52 620).33 Regarding mouse platelets, the combined data sets MID1-5 gave fractional information on 54 248 transcripts, expressed as log2-transformed rpkm/tpm values.

Quantified transcripts and proteins in human and mouse platelets from integrated data sets

| . | No. of genes (data sets) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Human platelets . | Human megakaryocytes . | Mouse platelets . | |

| Transcripts (RNA-seq) | |||

| Total quantified | 54 791 (5) | 52 620 (1) | 54 248 (5) |

| Total classified | 54 791 (5) | 52 620 (1) | 54 248 (5) |

| Protein encoding | 20 289 (5) | 20 077 (1) | 22 234 (5) |

| Orthologs quantified | 19 368 (5) | 19 368 (1) | 19 280 (5) |

| Proteins (MS) | |||

| Total identified | 6379 (5) | n.a. | 4684 (5) |

| Total quantified | 5823 (5) | n.a. | 4565 (5) |

| Orthologs quantified | 3909 (5) | n.a. | 3909 (5) |

| . | No. of genes (data sets) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Human platelets . | Human megakaryocytes . | Mouse platelets . | |

| Transcripts (RNA-seq) | |||

| Total quantified | 54 791 (5) | 52 620 (1) | 54 248 (5) |

| Total classified | 54 791 (5) | 52 620 (1) | 54 248 (5) |

| Protein encoding | 20 289 (5) | 20 077 (1) | 22 234 (5) |

| Orthologs quantified | 19 368 (5) | 19 368 (1) | 19 280 (5) |

| Proteins (MS) | |||

| Total identified | 6379 (5) | n.a. | 4684 (5) |

| Total quantified | 5823 (5) | n.a. | 4565 (5) |

| Orthologs quantified | 3909 (5) | n.a. | 3909 (5) |

Indicated are total numbers of unique gene-linked transcripts and proteins derived from 5 data sets of human and mouse platelets. For full lists, see supplemental Files 2 (human-based) and 3 (mouse-based).

MS, mass spectrometry; n.a., not available.

Quantitative alignment of the data sets resulted in overall high correlations between the 5 human and mouse platelet transcriptomes, with an R value ≥0.95, of which only the smaller-sized sets ID3 and MID2 were deviant, with R values ranging from 0.83 to 0.88 (supplemental Figure 3). The megakaryocyte transcriptome differed more, with an R value of 0.77. The number of quantified protein-expressing transcripts were 19 368 for humans and 19 279 for mice (Table 1).

By a similar approach, we combined 5 calibrated proteomes from well-purified human and mouse platelets (PROT_1D1-5 and PROT_MID1-5, respectively). Data set integration provided levels of 6379 human and 4563 mouse platelet proteins (Table 1). The lower number for mice is explained by incomplete knowledge of the amino acid sequence of many proteins in C57BL/6 mice.40 Comparison showed a remarkably high similarity of the individual mouse platelet and human platelet proteomes, with R values ranging from 0.78 to 0.97 (supplemental Figure 4).

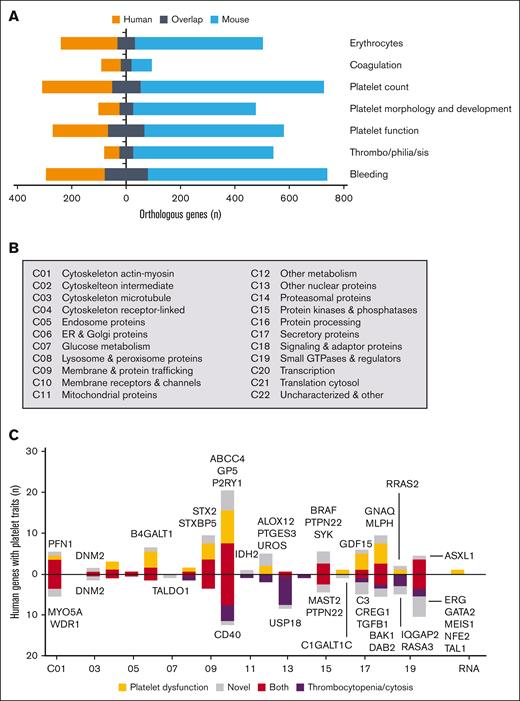

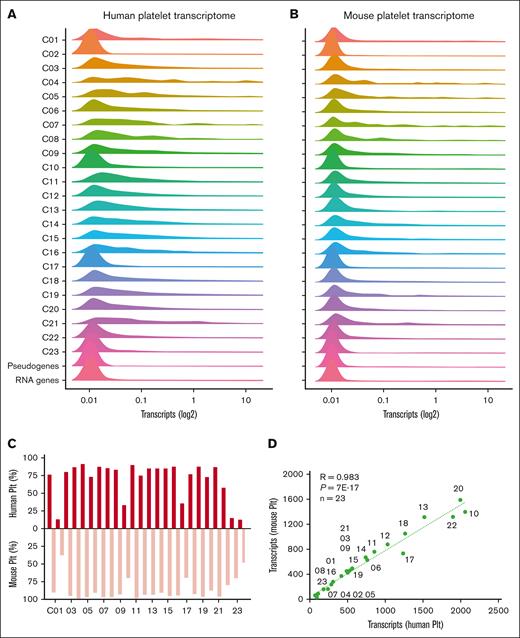

For the combined human and mouse platelet transcripts, we evaluated the quantitative distribution profiles per protein function class (Figure 2A-B). This effort pointed to a high interspecies similarity. Low-level transcripts were most abundant in humans and mice in specific classes (C02 [cytoskeleton intermediate]; C10 [membrane receptors and channels]; C17 [secretory proteins]; and C22 [uncharacterized proteins]) and furthermore in pseudogenes and RNA genes. Similar also were the fractions (Figure 2C) and numbers (Figure 2D) of transcripts per class when comparing human and mouse platelets.

Distribution profiles of orthologous transcripts in human and mouse platelets per function class. Quantified transcripts in human platelets (n = 54 790) and mouse platelets (n = 54 247) were assigned to 23 protein function classes, RNA genes, or pseudogenes. Histograms are given per class (100%) of mean fpkm/rpkm values (log2+1) for human platelets (A) and mouse platelets (B). (C) Percentage fractions of relevant transcripts (>0.03) per class (total 100%). (D) Correlation of relevant transcripts per class between human and mouse platelets. Plt, platelet.

Distribution profiles of orthologous transcripts in human and mouse platelets per function class. Quantified transcripts in human platelets (n = 54 790) and mouse platelets (n = 54 247) were assigned to 23 protein function classes, RNA genes, or pseudogenes. Histograms are given per class (100%) of mean fpkm/rpkm values (log2+1) for human platelets (A) and mouse platelets (B). (C) Percentage fractions of relevant transcripts (>0.03) per class (total 100%). (D) Correlation of relevant transcripts per class between human and mouse platelets. Plt, platelet.

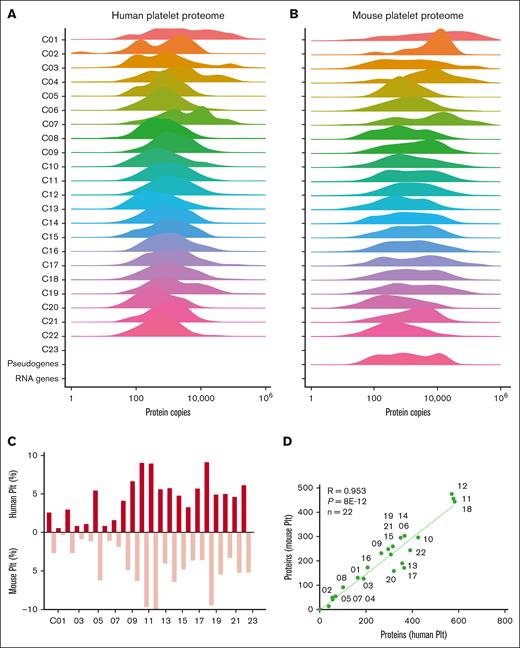

Concerning the profiles of protein copy numbers per class, we noted small shifts to the right for mouse platelets, compared to human platelets (Figure 3A-B). Of note here, we did not normalize the published calibrations for platelets from either species. Yet, the highest copy numbers were present in the same classes (C01, C03, C07, and C19). High concordance between species also appeared from the ratios of identified proteins relative to transcripts (Figure 3C) and the numbers of proteins per class, with an R value of 0.95 (Figure 3D). Together, these alignments highlighted high qualitative comparability of the within-species and interspecies transcriptome and proteome data sets.

Distribution profiles of orthologous platelet proteins in human and mouse platelets per function class. Quantified proteins in human platelets (n = 6379) and mouse platelets (n = 4684) were assigned to 23 protein function classes. Histograms are given per class (100%) of mean copy numbers for human platelets (A) and mouse platelets (B). (C) Percentage fractions of identified proteins per class (total 100%). (D) Correlation of identified proteins per class between human and mouse platelets. Plt, platelet.

Distribution profiles of orthologous platelet proteins in human and mouse platelets per function class. Quantified proteins in human platelets (n = 6379) and mouse platelets (n = 4684) were assigned to 23 protein function classes. Histograms are given per class (100%) of mean copy numbers for human platelets (A) and mouse platelets (B). (C) Percentage fractions of identified proteins per class (total 100%). (D) Correlation of identified proteins per class between human and mouse platelets. Plt, platelet.

Assessment of orthologous human and mouse platelet transcriptomes and proteomes

To directly compare the transcriptomes, we filtered the human and mouse platelet data sets for orthologous genes and renormalized these per set to tpm values. This resulted in quantitative information on 19 368 human and 19 229 mouse gene transcripts (Table 1). Principal component analysis indicated a clear segregation of clusters between species (supplemental Figure 5A). This cluster separation was also seen by principal component analysis of the proteome data sets (supplemental Figure 5B). This consistent segregation between species prompted us to calculate mean values and variation coefficients of the human and mouse transcriptomes and proteomes (supplemental Files 2 and 3).

To assess those transcripts with relevant expression,33 we used the combined proteome data. Plots of binned log2(tpm + 1) values vs numbers of identified proteins resulted in cutoff levels of 0.03, above which transcripts were found with increased protein identification for both human and mouse platelets (supplemental Figure 6). Class-wise comparison of the transcript distribution profiles showed high similarities for either species (supplemental Figure 7). The corresponding histograms indicated that low-level transcripts were relatively abundant in 5 classes (C02, C10, C20, C22, and C23; supplemental Figure 8). Assuming a relevant protein translation above the cutoff level, we calculated a theoretical proteome of 15 500 gene products in human platelets and 13 500 in mouse platelets.

The similarity of gene products in the platelets prompted us to also compare mean transcript and protein levels. Plotting of the values of all orthologous human and mouse transcripts (n = 19 368) gave a correlation coefficient R of 0.75, in which especially the lower level transcripts substantially differed between species (Figure 4A). Plotting of mean protein copy numbers (n = 3909) resulted in a high correlation coefficient (R = 0.87; Figure 4B). The lower quantitative similarity of platelet transcriptomes can be explained by differences in messenger RNA (mRNA) stability, for instance due to interspecies differences in platelet size and circulation time.

Similarity of orthologous transcripts and proteins in human and mouse platelets. (A) Plot of transcript values [log2(tpm + 1); tpm normalized; means of 5 transcriptomes] comparing human and mouse platelets. (B) Plot of protein copy numbers (calibrated; means of 5 proteomes) comparing human and mouse platelets. Shown are results of regression analysis with indicated number of gene products. (C) Partial overlap (in black) of orthologous transcripts in human and mouse platelets per function class (C01-C23; RNA genes; pseudogenes). The relevant transcript level was set at 0.03. (D) Partial overlap (in black) of detected proteins in human and mouse platelets per function class. Not identified means absent in proteome but present in transcriptome. Plt, platelets.

Similarity of orthologous transcripts and proteins in human and mouse platelets. (A) Plot of transcript values [log2(tpm + 1); tpm normalized; means of 5 transcriptomes] comparing human and mouse platelets. (B) Plot of protein copy numbers (calibrated; means of 5 proteomes) comparing human and mouse platelets. Shown are results of regression analysis with indicated number of gene products. (C) Partial overlap (in black) of orthologous transcripts in human and mouse platelets per function class (C01-C23; RNA genes; pseudogenes). The relevant transcript level was set at 0.03. (D) Partial overlap (in black) of detected proteins in human and mouse platelets per function class. Not identified means absent in proteome but present in transcriptome. Plt, platelets.

Class-wise comparison of relevant transcripts in human and mouse platelets, however, demonstrated a high overlap (Figure 4C). For the total 18 041 protein-encoding genes, the overlap percentages were 83% for human and 96% for mouse transcripts. This difference is explained by the lower transcript numbers in mouse platelets for membrane receptors and channels (C10), secretory proteins (C17), transcription proteins (C20), and uncharacterized proteins (C22). Regarding the identified proteins, we calculated lower overlap rates of 65% and 88% (Figure 4D), caused by as yet incompleteness of the 2 proteomes. Markedly for both human (R = 0.29) and mouse platelets (R = 0.34), transcript levels poorly correlated with protein copy numbers (supplemental Figure 9). This result is in agreement with an earlier conclusion that in human platelets, protein abundance is maximized but not otherwise related to the mRNA level.33 On the contrary, only a few transcripts showed a high expression in one species and a low expression in the other, a rare example being mouse F2rl2 encoding for the thrombin receptor PAR3 (supplemental Table 11). Taken together, this combined analysis points to a high qualitative similarity between the transcriptomes of human and mouse platelets, with a higher quantitative similarity of the 2 proteomes.

Finding novel hemostasis- and platelet-regulating genes from mouse phenotypes

Of the assembled 3474 genes with links to hemostasis- and platelet-related phenotypes, the majority of 85% to 90% showed relevant expression of transcripts in mouse and human platelets, whereas copy numbers of half of the corresponding proteins were available (supplemental Figure 10). Phenotyping showed that most of the human genes were linked to increased bleeding, low platelet function/size, thrombocytopenia, or anemia (supplemental Figure 10A, green color). This was also true for the higher number of mouse genes, although these in part also scored for increased thrombosis or thrombocytosis (supplemental Figure 10B, red color). When counting the syndromic genes, that is, those with phenotypes not confined to blood aberrances in human and/or mice, approximately half fell into this category. Summation of the human ad mouse phenotype scores per class indicated that membrane receptors and channels (C10), signaling proteins (C15 and C18), nuclear proteins (C13 and C20), and secretory proteins (C17) were the most present (supplemental Figure 11).

We considered that the search for combinations of mouse phenotypes can help in the identification of novel genes contributing to human hemostasis. We first counted the mouse and human genes linked to any bleeding or to bleeding in combination with another phenotype (supplemental Table 12). For mice, the highest numbers were obtained for bleeding in combination with platelet dysfunction (n = 211; syndromic 54%) or with thrombocytopenia (n = 93; syndromic 64%; supplemental Table 12B). For humans, the numbers were substantially lower (n = 81 and n = 73) and were mostly covered by the set of 150 reference genes for bleeding-related disorders. Overall, the mouse genes with a bleeding and platelet phenotype overlapped by 20% with human genes with a platelet trait in GWAS. This suggests that the association studies, based on flow-cytometric platelet characteristics, are relevant but do not fully predict platelet defects relevant to hemostasis.

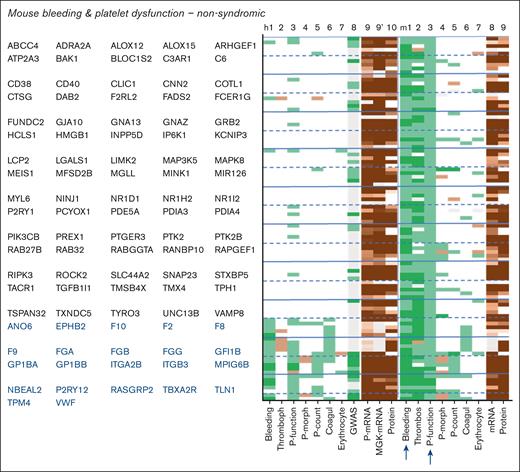

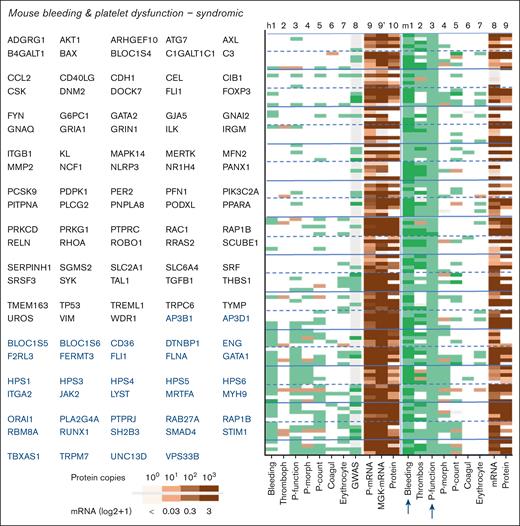

Close examination of the 211 mouse genes linked to bleeding plus platelet dysfunction, of which 97 nonsyndromic (Figure 5) and 114 syndromic (Figure 6) indicated thrombocytopenia as the most frequent cophenotype. The orthologous human genes were linked to only a few phenotypes, with an exception of 58 reference genes. In comparison, the 93 mouse genes linked to bleeding plus thrombocytopenia (29 nonsyndromic) incidentally coscored for platelet dysfunction (Figure 7A,B). Furthermore, the mouse genes linked to bleeding and coagulation defects frequently scored for reduced arterial thrombosis (Figure 7C,D).

Phenotype profiles of nonsyndromic genes linked to bleeding in combination with platelet dysfunction in mouse. Syndromic genes from supplemental File 1 were filtered for bleeding plus platelet dysfunction in mouse. Indicated in blue type are orthologous human genes from the reference list (known link to hemostasis). Phenotype scoring for humans (h) and mice (m) included the following: 1, bleeding; 2, thrombophilia/arterial thrombosis tendency; 3, platelet function; 4, platelet morphology and development; 5, platelet count; 6, coagulation dysfunction; 7, erythrocyte characteristics; 8, platelet traits from human GWAS (supplemental Figure 1). Indicated are also mean levels of platelet and megakaryocyte transcripts and platelet protein copy numbers. Extended phenotype descriptions per gene are given in supplemental File 1. Coagul, coagulation; MGK, megakaryocyte; P-count, platelet count; P-morph, platelet morphology; P-mRNA, platelet mRNA.

Phenotype profiles of nonsyndromic genes linked to bleeding in combination with platelet dysfunction in mouse. Syndromic genes from supplemental File 1 were filtered for bleeding plus platelet dysfunction in mouse. Indicated in blue type are orthologous human genes from the reference list (known link to hemostasis). Phenotype scoring for humans (h) and mice (m) included the following: 1, bleeding; 2, thrombophilia/arterial thrombosis tendency; 3, platelet function; 4, platelet morphology and development; 5, platelet count; 6, coagulation dysfunction; 7, erythrocyte characteristics; 8, platelet traits from human GWAS (supplemental Figure 1). Indicated are also mean levels of platelet and megakaryocyte transcripts and platelet protein copy numbers. Extended phenotype descriptions per gene are given in supplemental File 1. Coagul, coagulation; MGK, megakaryocyte; P-count, platelet count; P-morph, platelet morphology; P-mRNA, platelet mRNA.

Phenotype profiles of syndromic genes linked to bleeding in combination with platelet dysfunction in mouse. Syndromic genes from supplemental File 1 were filtered for bleeding plus platelet dysfunction in mouse. Phenotype scoring for human (h) and mouse (m) included was as described in Figure 5.

Phenotype profiles of syndromic genes linked to bleeding in combination with platelet dysfunction in mouse. Syndromic genes from supplemental File 1 were filtered for bleeding plus platelet dysfunction in mouse. Phenotype scoring for human (h) and mouse (m) included was as described in Figure 5.

Phenotype profiles of genes linked to bleeding in combination with thrombocytopenia or coagulation defects in mouse. Filtering of supplemental File 1 was for nonsyndromic (A) or syndromic (B) thrombocytopenia or for nonsyndromic (C) or syndromic (D) coagulation defects. Reference human genes are indicated in blue type. Phenotype scoring was as indicated in Figure 5.

Phenotype profiles of genes linked to bleeding in combination with thrombocytopenia or coagulation defects in mouse. Filtering of supplemental File 1 was for nonsyndromic (A) or syndromic (B) thrombocytopenia or for nonsyndromic (C) or syndromic (D) coagulation defects. Reference human genes are indicated in blue type. Phenotype scoring was as indicated in Figure 5.

Regarding the human phenotypes, the list of 124 (or 135) genes linked to human bleeding plus platelet dysfunction (or bleeding plus thrombocytopenia) showed high overlap with mouse phenotypes, most strongly for the 79 (or 62) reference genes, as depicted in supplemental Figure 12 (supplemental Figure 13). The number of human genes connected to bleeding plus a coagulation defect was lower, amounting to 60 (20 nonsyndromic), including the 42 reference genes (supplemental Figure 14).

We further examined how often a bleeding phenotype was combined with erythrocyte anomalies, particularly anemia. In mice, this concerned 64 genes, mostly syndromic, which often also scored for thrombocytopenia (supplemental Figure 15). In humans, as many as 102 genes, almost all syndromic with several transcription factors, showed this combination with anemia. Here, thrombocytopenia was again the most common cophenotype (supplemental Figure 16). Interestingly, the majority of genes linked to anemia appeared to be expressed in mouse and human platelets. Overall, the gene fractions with a GWAS score raised to 32% to 48% for the combination of bleeding plus altered blood cell counts.

Filtering for bleeding as an isolated phenotype resulted in 168 mouse genes (supplemental Figure 17) and 50 human genes (supplemental Figure 18). The mouse list (with incidental human phenotypes) was mostly derived from International Mouse Phenotyping knockouts and may serve as a suitable resource for future platelet-related studies. The frequent combination of scores for bleeding and thrombophilia in humans (n = 53 genes; supplemental Figure 18C-D) is explained by the prothrombotic effects of gain-of-function mutations along with gene expression defects.

As a contribution to the search for antithrombotic targets not affecting hemostasis, we examined mouse genes with negative scores for experimental arterial thrombosis in combination with increased bleeding (n = 187; supplemental Figure 19) or without bleeding (n = 139; supplemental Figure 20). Interestingly, both sets had platelet dysfunction as a common cophenotype but not thrombocytopenia or anemia. With the exception of reference genes, the phenotypes were mostly not observed so far in humans. Promising targets from the nonbleeding mouse list may be platelet-expressed CXCL12, DUSP3, GP6, and PF4.46-49

We finally screened the literature to search for a role for mouse genes with bleeding plus platelet traits (dysfunction or thrombocytopenia) in human hemostasis. This validation effort resulted in 42 human genes, all with relevant expression levels in platelets (supplemental Table 13). These novel genes encoded in majority for membrane receptors and channels (n = 5), signaling proteins including GTPase regulators (n = 13), and transcription regulators (ASXL1, ERG, GATA2, MEIS1, NFE2, and TAL1; Figure 1C). Interestingly, for these 42 genes, the ClinVar database reported high numbers (mean ± standard deviation, 131 ± 179; n = 42) of (likely) pathogenic variants (supplemental Table 13). Collectively, these findings highlight the predictive power of a combined platelet multiomics and phenotypic analysis, because it established roles for an unexpectedly large number of genes in hemostasis and thrombosis. We infer that our work can serve as a valuable resource for researchers and clinicians further unraveling the genetics and treatment of platelet-related disorders.

Discussion

By systematically analyzing available information from mouse- and human-oriented databases, we identified 3474 orthologous genes linked to hemostatic or platelet phenotypes, the majority of which with relevant expression levels in human platelets. For 42 of the mouse genes, we confirmed a linkage with human platelet function or count, which was supported by the frequent detection of pathological genetic variants in ClinVar listings. For these and likely other genes, geneticists may confirm a role in human hemostasis, in addition to the current 150 reference genes. Regarding the 2017 genes with platelet traits from GWAS analyses, several of these appeared in the mouse bleeding lists as fractions of ∼20%, which increased to 32% to 48% for cophenotypes of bleeding with thrombocytopenia or anemia. Regarding the 1816 genes typed as GWAS only, it may be a promising effort to examine hemostasis-linked phenotypes in knockout models. We also found that ∼40% of the human and mouse genes were linked to syndromic (nonblood) phenotypes, suggesting the presence of a crypto-hemostatic phenotype in complex diseases.

From the integrative transcriptome analysis, we obtained classified and fractional log2(i + 1) information on 54 791 human and 54 248 mouse genes. This quantification effort expands our knowledge of platelet transcriptomes, because earlier reports described transcript numbers of only 6.0 × 103 to 8.5 × 103,30 10 × 103,32 or 14.8 × 103.33 The genome-wide comparison of human and mouse platelet transcriptomes in general revealed a higher qualitative than quantitative similarity between species. On the contrary, the platelet proteomes showed a high quantitative similarity reaching 87%. Earlier studies based on lower numbers of platelet transcripts and proteins have been unclear in this matter.32,35,36,50 Thus, the current large data sets will be useful as a reference for future platelet omics analyses in humans and mice.

Our interspecies gene alignment resulted in 19 279 to 19 366 orthologous transcripts. Overlap percentages for relevant expression in the combined transcriptomes were high, that is, 83% for human-to-mouse and 96% for mouse-to-human platelet transcripts. The remaining differences between species particularly existed in the classes of membrane receptors/channels, secretory proteins, transcription-related proteins, and uncharacterized proteins. The calculated mean proteomes still comprised only 31% and 21% of the protein-encoding transcripts in humans and mice, respectively. Missing in the proteomes were in particular dozens of membrane solute carriers, olfactory and taste receptors, immunoglobulin variable chains, and zinc finger proteins. Absence of these proteins can be explained by technical limitations, low levels of transcripts or proteins, perinuclear localization in megakaryocytes, and, furthermore, by incompleteness of current UniProt assignments.40 Altogether, the aligned human and mouse transcript-protein sets were found to be qualitatively related but not identical. Of note, we did not consider differences due to age, sex, or race/strain, which modify platelet microRNA-mRNA networks.50 We also did not take into account the differences between platelet populations (juvenile and aging) within subjects.51

In recent years, RNA-seq has emerged as a powerful technology for transcriptome profiling, capable of detecting low abundance transcripts.52 In this comparative analysis, we used fractional fpkm (ComBat normalized) and tpm values, which compensate for sequencing depth and gene length of the transcripts. A linear across-species renormalization to tpm values then allowed for straightforward comparison of the human and mouse platelet transcripts. We did not apply DESeq2 median count normalization methods, given that this is not a common practice in the comparison of different cell types. Principal component analysis indicated that the obtained transcript and protein copy values partly deviated between data sets. This variation can be explained by platelet sources, sample preparations, and (pre)analytical differences, such as cDNA sequencing procedures and mass spectrometer–dependent resolution.40 Impurity of the used platelet preparations was considered a minor factor, given the overall low abundance of specific components of other blood cells.

Calculations based on RNA-seq analyses from lymphoblasts have estimated the mRNA content at 50 000 to 300 000 copies per cell.53 Accordingly, in such a cell, only a few thousand genes can deliver mRNA in the range of 1 to 30 copies.53 Taking a 100-times lower volume, single human platelets (newly formed) then contain only 500 to 3000 mRNA molecules (2 kDa), partly bound to ribosomes. Considering the present identification of >19k relevant transcripts, a given platelet will hold a very minor, likely random, proportion of the total mRNA pool, inherited from the parent megakaryocyte. Assuming 3000 mRNA copies per platelet, calculation learns that log2(tpm + 1) values of 0.1 and 0.01 correspond to 1 mRNA molecule per 4.4 × 103 and 4.4 × 104 platelets, respectively. By implication, most of the identified transcripts will be present in only small fractions of the total platelet pool. The transcript differences between single platelets become even higher when taking into account the high mRNA degradation upon platelet aging.31 Irrespective of this, we consider that the platelet (population) transcriptome comprises an important biomarker resource of the expressed genes in parent megakaryocytes.

In summary, our effort to combine human and mouse platelet transcriptomes and proteomes, along with phenotype analysis, reveals the following: (i) high interspecies similarity in structure and function; (ii) >400 novel genes linked to bleeding in combination with platelet, erythrocyte, or coagulation dysfunctions; (iii) preponderance of genes with syndromic phenotypes; and (iv) largely overlapping sets of transcripts and proteins in human and mouse platelets. This comprehensive work can serve as a support for the interpretation and contextualization of transcriptomics and proteomics in relation to platelet-linked diseases, including bleeding disorders.

Acknowledgments

J.H., I.P., and I.D.S. were supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement (TAPAS number 766118). M.F. was supported by the British Heart Foundation (FS/18/53/22863) and by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Exeter Biomedical Research Centre. Further research support came from the Centre for Molecular Translational Medicine (INCOAG, MICRO-BAT) (J.W.M.H.), the Ministerium für Innovation, Wissenschaft und Forschung from Nordrhein-Westfalen (A.S.), the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF 01EO1503; A.S.), Cluster4Future curATime – megaTArget (BMBF 03ZU1202GA; W.R.); Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (ZA 639/4-1 and JU 2735/2-1 [A.S. and F.A.S.] and 318346496 - SFB1292/2 TP19N [F.M.]); and China Scholarship Council (X.G.).

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funders had no role in the design and execution of the study, or in the decision to publish the results.

Authorship

Contribution: J.H., F.M., F.A.S., F.S., B.d.L., I.D.S., I.P., L.G., X.G., E.A.M., and C.S. analyzed and interpreted data; B.d.L., K.L., N.V.M., S.S., S.W., and A.S. provided essential tools and revised the manuscript; and M.F., J.W.M.H., F.M., M.T.R., and W.R. designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and supervised and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.A.S., I.D.S., F.S., and B.d.L. are employees of Synapse Research Institute Maastricht. J.W.M.H. is a consultant at Synapse Research Institute Maastricht. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jingnan Huang, Department of Nephrology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Southern University of Science and Technology, 1098 Xueyuan Blvd, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518071, China; email: jingnan_huang@outlook.com; and Johan W. M. Heemskerk, Synapse Research Institute, Koningin Emmaplein 7, 6217 KD Maastricht, The Netherlands; email: jwmheem722@outlook.com.

References

Author notes

W.R., M.F., and J.W.M.H. contributed equally to this work.

All raw data have been deposited at the sites as indicated in the supplementary Materials.

All derived primary data are incorporated as data files (currently as shortened versions; completed versions to be added on request of the editor). The data files are available on request from the corresponding authors, Jingnan Huang (jingnan_huang@outlook.com) and Johan W. M. Heemskerk (jwmheem722@outlook.com).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Similarity of orthologous transcripts and proteins in human and mouse platelets. (A) Plot of transcript values [log2(tpm + 1); tpm normalized; means of 5 transcriptomes] comparing human and mouse platelets. (B) Plot of protein copy numbers (calibrated; means of 5 proteomes) comparing human and mouse platelets. Shown are results of regression analysis with indicated number of gene products. (C) Partial overlap (in black) of orthologous transcripts in human and mouse platelets per function class (C01-C23; RNA genes; pseudogenes). The relevant transcript level was set at 0.03. (D) Partial overlap (in black) of detected proteins in human and mouse platelets per function class. Not identified means absent in proteome but present in transcriptome. Plt, platelets.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodvth/2/3/10.1016_j.bvth.2025.100068/2/m_bvth_vth-2024-000259-gr4.jpeg?Expires=1764613803&Signature=Rx5ewCiI~kRwmJARO9Le7rNkxqKVCnKLSxxgrzzLFOVtdARYW5Hm-dPqKe~6g6bOunQKeoLxMf44eHx-2USWC6APpSvl1cSvCX9I4cEUH8Z1lwBuWkg4sDxoBPDeZLeuvMU23N0VJPBmv2C8nVLtsbFZMEfh75PtIavsRnVR08TIiAMcMsWxdsEHjsU-h0A9xWaHuEgqMP1S5fzX-n0qSG4kKq17rcTbKBk4XeHnzHzk7hu3IU7ubOBy7v~OkPHTaOheMg~Iwl8fIG-JS2GM6w3~IF-A7wch2CP3Pt-woJrfHrUxFyFow6owzcJrP8QryRjX~RjbVtva6W9ZAzvrVA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)