Key Points

MT mutations are associated with the development of AIC.

Rare variants in MT gene are associated with AIC and lower immunoglobulin G levels.

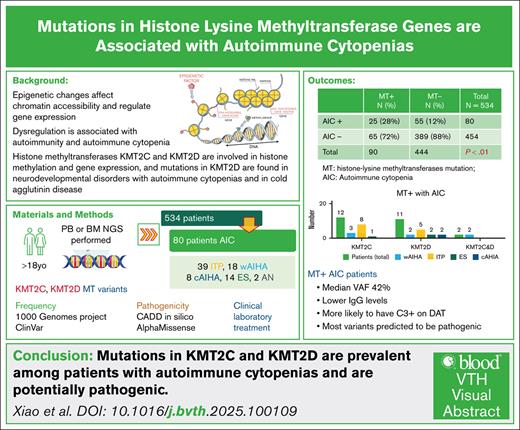

Visual Abstract

Epigenetic dysregulation is increasingly recognized as a contributor to autoimmunity and autoimmune cytopenias (AIC). Histone lysine methyltransferases (MTs) are key regulators of gene expression through epigenetic modification. Germline MT mutations are associated with immunodeficiency syndromes such as Kabuki syndrome, which frequently co-occurs with AIC, while somatic KMT2D mutations have been reported in cold agglutinin disease. This study aimed to (1) determine the frequency of mutations in histone methyltransferase genes (KMT2D, KMT2A, KMT2C, and KDM6A) among patients with AIC, and (2) compare clinical, laboratory, and immunologic characteristics, as well as treatment responses, between patients with and without MT mutations. We retrospectively analyzed 534 patients who underwent comprehensive next-generation sequencing of bone marrow or peripheral blood; 80 had a diagnosis of AIC. Patients were categorized as MT-positive (MT⁺) or MT-negative (MT⁻) based on the presence of mutations in the specified genes. MT⁺ patients were significantly more likely to develop AIC compared with MT⁻ patients (25/90 vs 55/444). MT⁺ patients with AIC exhibited significantly lower serum immunoglobulin G levels, and those with autoimmune hemolytic anemia were more likely to demonstrate complement involvement on the direct antiglobulin test. MT variants identified in the AIC cohort were absent from the 1000 Genomes database and were predicted to be among the top 1% of the most deleterious variants based on Phred scores. These findings suggest that mutations in histone methyltransferase genes may play a role in the development of AIC. Prospective studies are warranted to validate these associations and to elucidate the epigenetic mechanisms underlying autoimmunity, which may ultimately support biomarker discovery and personalized approaches to disease management.

Introduction

Epigenetic modification plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression by altering the accessibility of the chromatin to transcriptional regulatory factors without changing the genomic sequence.1 The pathophysiology of autoimmune disorders is complex and is not fully understood; however, recent studies report that epigenetic modification plays an essential role.2 Epigenetic mechanisms involve DNA methylation, posttranslational histone tail modification, and noncoding RNA expression. The pathophysiology of various autoimmune disorders has been associated with changes in each of these 3 fundamental epigenetic processes.3 Two epigenetic modifiers, histone lysine N-methyltransferase 2C (KMT2C) and KMT2D, histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methyltransferases, and lysine-specific demethylase 6A (KDM6A), a histone H3K27 demethylase, are part of the nuclear regulatory complex, the KMT2C/D COMPASS complex (complex of proteins associated with set1) that regulates histone tail methylation, and plays a crucial role in the regulation of development, differentiation, metabolism, and tumor suppression.4,5 Mutations in KMT2C and KMT2D genes are causes of rare genetic neurodevelopmental disorders, including Kleefstra syndrome6 and Kabuki syndrome, respectively. Kabuki syndrome is associated with problems in neurological, immunological, and skeletal system development. Autoimmune cytopenias (AICs), including immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) and autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), were reported in 7% and 4% of patients with Kabuki syndrome, respectively.7 Mutations in KMT2D were also seen in most patients with primary cold agglutinin disease, a rare form of AIHA.8 Therefore, we conducted a study to investigate the relationship between mutations in the histone lysine methyltransferase (MT) genes KMT2C and KMT2D, and AIC.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

Using the ATLAS data mining platform, we conducted a retrospective analysis to identify all adult patients (aged ≥18 years) diagnosed with AIC who underwent comprehensive next-generation sequencing (NGS) at Montefiore Medical Center between January 2012 and April 2024. NGS was performed on peripheral blood or bone marrow samples obtained during evaluation for cytopenia and included a targeted panel comprising 164 genes associated with myeloid disorders and 128 genes associated with lymphoid malignancies (NeoGenomics, Fort Myers, FL). From this cohort, patients with a confirmed diagnosis of AIC were selected for further analysis.

AIC diagnosis included ITP (diagnosis based on 2019 American Society of Hematology Clinical Practice Guidelines9), warm AIHA (wAIHA) and cold AIHA (cAIHA; diagnosis based on International Consensus Meeting10) and Evans syndrome (ES),11,12 and autoimmune neutropenia (diagnosis based on 2023 European Hematology Association guideline13). Patients with idiopathic AIC and AIC associated with chronic lymphoproliferative disorder or autoimmune disease were included. Patients with cytopenia meeting the following exclusion criteria were excluded: (1) cytopenias in the setting of nutritional deficiency, secondary to medications, myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloproliferative neoplasm, acute leukemia, inherited and acquired bone marrow failure syndrome, or myelophthisis; (2) secondary AIC, including pregnancy-associated, infection-associated causes (including recently coronavirus disease 2019 related); and (3) missing and/or insufficient NGS/clinical data.

Patients were categorized into 2 groups based on the presence or absence of mutations in the MT genes (MT+ and MT–, respectively). MT– patients served as the control group.

Data collection

Data mining software, ATLAS, was used to extract data from electronic medical records. Patients with comprehensive NGS testing available were screened for the presence of AIC. Only single-nuclear variants (SNVs) in KMT2C and KMT2D with reported variant allelic frequency (VAF) of >2% were considered. Patients with AIC were categorized into 2 groups based on the presence or absence of SNVs in the MT genes (MT+ and MT–).

Demographic information (age of diagnosis, sex, race, and ethnicity), laboratory results (direct Coombs test result, immunoglobulin G [IgG], IgA, IgM levels, absolute neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, nadir hemoglobin for ES and AIHA, and nadir platelet count for ES and ITP), and outcome data (associated autoimmune disorders, treatment requirement, number of lines of therapy, depth of response, and infectious complications) were collected.

Definitions of diagnosis and response, including partial response/response, complete response (CR), corticosteroid dependence, and refractoriness for ITP were based on the ITP International Working Group,14 and for AIHA and ES on the first International Consensus recommendations.10 Two researchers, including 1 senior author, blindly and independently collected and reviewed data, and discrepancies were resolved with discussion.

NGS

NGS data were collected from patients with SNVs in KMT2C and KMT2D.

Only peripheral blood and bone marrow samples were used for analysis, limiting our ability to distinguish somatic mutations from germ line variants. SNVs seen in MT+ genes (KMT2C/D) were cross-referenced with the 1000 Genomes Project population database,15 as well as the ClinVar database16 to compare with the frequency of variants in the general healthy population. Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) in silico prediction algorithm was used to score the potential deleterious effect of MT variants.9 CADD database scores the potential deleterious effect of the mutations where a Phred score of ≥10 indicates 10% of the most deleterious substitutions that can happen to the human genome, and a score ≥20 would indicate 1% of the most deleterious substitutions. In addition, AlphaMissense, a machine learning model that can analyze missense variants and predict their pathogenicity with 90% accuracy, was used to evaluate the pathogenicity of missense variants.17

Statistical analysis

For descriptive statistics, quantitative data were presented with median and interquartile range, and qualitative data by number and frequency (percent). The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for continuous variables, and the χ2 test and Fisher exact test were used for categorical variables. Multivariate analysis was conducted to explore the relationships between the variable of interest and platelet count and hemoglobin level. All P values were 2-tailed, and a P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R program software (version 4.1.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 534 patients who underwent NGS testing were identified. Ninety patients had mutations in MT genes (16.8%). Only peripheral blood and bone marrow samples were used for analysis, limiting our ability to distinguish somatic mutations from germ line variants. Eighty patients (15.0%) were diagnosed with AIC. Among the 80 patients with AIC, 25 (25/90 [27.8%]) had MT mutations, and 55 (55/444 [12.4%]) were without mutations (P = .00025; Table 1). Among 65 patients who had MT mutations without AIC, 14 were diagnosed with myeloid disease, 18 were diagnosed with lymphoid disease, 16 with cell abnormalities without a definitive diagnosis, 4 patients had venous thrombotic events as primary diagnosis, 4 patients with nutritional anemia, and the rest of the patients had other diagnosis. The details are included in Table 2. Additionally, 8 of them also had concurrent autoimmune disorders (3 systemic lupus erythematosus, and 1 with rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma, systemic sclerosis, and multiple sclerosis, respectively). Among 80 patients with AIC, 39 (48.7%) had ITP, 18 (22.5%) had wAIHA, 8 (10%) had cAIHA, 14 (17.5%) had ES, and 2 (2.5%) had autoimmune neutropenia. MT SNVs were present in 25 (31.3%) patients with AIC, including 12 (48%) with KMT2C SNVs, 11 patients had KMT2D SNVs (44%; 1 patient had 2 KMT2D SNVs), and 2 patients had both KMT2C and KMT2D SNVs. Most patients with KMT2C SNVs had ITP (8 [66.7%]), 3 had wAIHA, and 1 had ES. Among the 11 patients with KMT2D SNVs, 5 had ITP, 2 had wAIHA, 1 had cAIHA, and 2 had ES, 1 with 2 KMT2D SNVs had cAIHA; 2 patients with both KMT2D and KMT2C mutations were diagnosed with wAIHA. In addition, 1 of them had IgG κ smoldering myeloma and the other 1 had liver transplant before wAIHA onset. In addition, clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential–associated mutations were also detected in patients with AIC. There were 2 patients with KMT2D SNVs who carried RUNX1 mutation and DNMT3A mutation, respectively. One patient with both KMT2D and KMT2C also carried TET2 mutation. In the MT– group, there were 4 patients with TET2 mutation, 7 patients with DNMT3A mutation, 3 patients with ASXL2 mutation, 3 patients with SH2B3 mutation, and 1 patient with IDH2 mutation.

Total patients who underwent NGS testing

| Presence of AIC . | MT+ . | MT– . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 25 | 55 | 80 |

| No | 65 | 389 | 454 |

| Total | 90 | 444 | 534 |

| Presence of AIC . | MT+ . | MT– . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 25 | 55 | 80 |

| No | 65 | 389 | 454 |

| Total | 90 | 444 | 534 |

Diagnosis for patients who were MT+ AIC–

| Category . | Diagnosis . |

|---|---|

| Myeloid disease, N = 14 | MDS (4), ET (4), AML (3), HES (2), and chronic eosinophilic leukemia (1) |

| Lymphoid disease, N = 18 | CLL (5), ALL (2), MCL (2), FL (2), ATLL (1), DLBCL (1), CTL (1), T-LGL (1), LPL (1), PEL (1), and HL (1) |

| Cell abnormality without definitive diagnosis, N = 16 | Thrombocytopenia (7), neutropenia (4), pancytopenia (3), leukocytosis (1), and macrocytosis (1) |

| Anemia, N = 5 | Iron deficiency anemia (2), vitamin B12 deficiency anemia (2), and sickle cell anemia (1) |

| Other, N = 12 | Venous thrombotic event (4), MGUS (2), bone marrow failure syndrome (2), CVID (1), Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (1), HLH (1), and small cell lung cancer (1) |

| Category . | Diagnosis . |

|---|---|

| Myeloid disease, N = 14 | MDS (4), ET (4), AML (3), HES (2), and chronic eosinophilic leukemia (1) |

| Lymphoid disease, N = 18 | CLL (5), ALL (2), MCL (2), FL (2), ATLL (1), DLBCL (1), CTL (1), T-LGL (1), LPL (1), PEL (1), and HL (1) |

| Cell abnormality without definitive diagnosis, N = 16 | Thrombocytopenia (7), neutropenia (4), pancytopenia (3), leukocytosis (1), and macrocytosis (1) |

| Anemia, N = 5 | Iron deficiency anemia (2), vitamin B12 deficiency anemia (2), and sickle cell anemia (1) |

| Other, N = 12 | Venous thrombotic event (4), MGUS (2), bone marrow failure syndrome (2), CVID (1), Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (1), HLH (1), and small cell lung cancer (1) |

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ATLL, adult T-cell leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CTL, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; CVID, common variable immunodeficiency; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ET, essential thrombocythemia; FL, follicular lymphoma; HES, hypereosinophilia syndrome; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; LPL, lymphoplasmacytic leukemia; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; PEL, primary effusion lymphoma; T-LGL, T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia.

The MT+ group has a higher proportion of Hispanic (60% vs 41%) and non-Hispanic White patients (20% vs 12%); however, this difference was not statistically significant. The median age at diagnosis of the MT+ patients was younger compared with MT– patients (age, 45.4 vs 50.1 years); however, there was no statistically significant difference (Table 3).

Demographic data of patients with AIC

| . | MT+, n = 25 . | MT–, n = 55 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of AIC onset, median (interquartile range), y | 45.4 (19.0-78.0) | 50.1 (34.2-67.0) | .45 |

| Sex, female, % | 60 | 69 | |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 5 (20) | 7 (13) | .11 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 5 (20) | 18 (33) | |

| Hispanic | 16 (60) | 23 (41) | |

| Other | 0 | 5 (14) | |

| N/A | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| AIC, n (%) | |||

| ITP | 13 (52) | 26 (46) | .80 |

| wAIHA | 7 (28) | 12 (21) | |

| cAIHA | 2 (8) | 6 (11) | |

| ES | 3 (12) | 10 (18) | |

| Autoimmune neutropenia | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

| . | MT+, n = 25 . | MT–, n = 55 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of AIC onset, median (interquartile range), y | 45.4 (19.0-78.0) | 50.1 (34.2-67.0) | .45 |

| Sex, female, % | 60 | 69 | |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 5 (20) | 7 (13) | .11 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 5 (20) | 18 (33) | |

| Hispanic | 16 (60) | 23 (41) | |

| Other | 0 | 5 (14) | |

| N/A | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| AIC, n (%) | |||

| ITP | 13 (52) | 26 (46) | .80 |

| wAIHA | 7 (28) | 12 (21) | |

| cAIHA | 2 (8) | 6 (11) | |

| ES | 3 (12) | 10 (18) | |

| Autoimmune neutropenia | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

N/A, not available.

Laboratory characteristics and clinical outcomes

Of 25 patients in the MT+ group, 6 (24%) had concurrent autoimmune disorder compared with 15 of 55 (27%) patients in the MT– group (P = .21). The MT+ group had significantly lower IgG levels (mean, 936 vs 1370 mg/dL; P = .001). MT+ patients with AIHA were more likely to have positive direct Coombs with complement involvement (58% vs 25%; P = .03). There were no significant differences in median nadir hemoglobin level and platelet counts.

Among patients with AIC who received therapy, the MT– group had a higher rate of CR (50% vs 32%), though not statistically significant. There was no difference in the treatment requirement, number of lines of treatment, overall response rate, infections, and hospitalizations secondary to infection between the 2 groups (Table 4).

Laboratory results and clinical outcomes of patients with AIC

| . | MT+, n = 25 . | MT–, n = 55 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coombs test | n = 12 | n = 28 | .03 |

| IgG only | 5 (42) | 14 (50) | |

| IgG and complement | 6 (50) | 3 (11) | |

| Complement only | 1 (10) | 4 (14) | |

| Negative | 0 (0) | 7 (25) | |

| IgG, mg/dL | 936 (687-1128) | 1370 (1012-1800) | .001 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count, ×103/μL | 0.8 (0.5-1.7) | 1.2 (0.7-2.52) | .14 |

| Absolute neutrophil count, ×103/μL | 4.3 (3.02-8.5) | 3.3 (2.05-6.28) | .09 |

| Nadir hemoglobin (g/dL) for AIHA and ES | n = 10 6.3 (5.48-8.2) | n = 20 6.1 (5.35-7.85) | .70 |

| Nadir platelet (×103/μL) for ITP and ES | n = 16 28.5 (8.5-95.50) | n = 36 18 (2-49.8) | .30 |

| Treatment requirement | 19 (76) | 48 (87) | .48 |

| No. of lines of treatment | n = 19 3 (1.5-3.5) | n = 48 3 (2-4) | .70 |

| Response | |||

| CR | 6/19 (32) | 24/48 (50) | .30 |

| Response | 11/19 (58) | 18/48 (38) | |

| No response | 2/19 (11) | 6/48 (12) | |

| Infection | |||

| Overall | 15 (60) | 33 (59) | 1 |

| Required hospitalization | 6 (24) | 12 (21) | .78 |

| . | MT+, n = 25 . | MT–, n = 55 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coombs test | n = 12 | n = 28 | .03 |

| IgG only | 5 (42) | 14 (50) | |

| IgG and complement | 6 (50) | 3 (11) | |

| Complement only | 1 (10) | 4 (14) | |

| Negative | 0 (0) | 7 (25) | |

| IgG, mg/dL | 936 (687-1128) | 1370 (1012-1800) | .001 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count, ×103/μL | 0.8 (0.5-1.7) | 1.2 (0.7-2.52) | .14 |

| Absolute neutrophil count, ×103/μL | 4.3 (3.02-8.5) | 3.3 (2.05-6.28) | .09 |

| Nadir hemoglobin (g/dL) for AIHA and ES | n = 10 6.3 (5.48-8.2) | n = 20 6.1 (5.35-7.85) | .70 |

| Nadir platelet (×103/μL) for ITP and ES | n = 16 28.5 (8.5-95.50) | n = 36 18 (2-49.8) | .30 |

| Treatment requirement | 19 (76) | 48 (87) | .48 |

| No. of lines of treatment | n = 19 3 (1.5-3.5) | n = 48 3 (2-4) | .70 |

| Response | |||

| CR | 6/19 (32) | 24/48 (50) | .30 |

| Response | 11/19 (58) | 18/48 (38) | |

| No response | 2/19 (11) | 6/48 (12) | |

| Infection | |||

| Overall | 15 (60) | 33 (59) | 1 |

| Required hospitalization | 6 (24) | 12 (21) | .78 |

Data are presented as n (%) and median (interquartile range). Statistically significant results are set in bold.

KMT2 variant analysis

In the cohort of 25 patients with AIC and MT mutations, the median VAF was 42.5% (interquartile range, 23.12%-49.42%).

To evaluate the prevalence of these variants in the general population, we compared them against the 1000 Genomes Project and ClinVar databases. Of the 27 SNVs identified in MT+ patients, 13 were not reported in ClinVar, whereas the remaining 14 were exceedingly rare, each with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of <0.0003. Only 3 SNVs were reported in 1000 Genomes database with MAF of <0.0003.

We assessed the potential functional impact of the identified SNVs using CADD in silico prediction algorithm. The mean Phred score was 19.1, with higher scores indicating greater predicted deleteriousness. Among the MT+ group, 15 of 25 patients had variants with scores >20, placing them within the top 1% of the most deleterious predicted variants.

Further analysis of the missense mutations using the AlphaMissense model revealed that 5 SNVs with Phred scores >20 were classified as pathogenic, 2 were of ambiguous pathogenicity, and 6 were predicted to be likely benign. Additionally, 1 SNV with a lower Phred score of 16.9 was categorized as likely pathogenic by AlphaMissense (Table 5).

KMT2 variant analysis

| MT variant . | VAF, % . | Phred score . | ClinVar interpretation . | AlphaMissense interpretation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMT2D N2517S NM_00348.3:c.7550A>G | 38.6 | 12.47 | Benign | Benign |

| KMT2D P2717S NM_003482.3:c.8148_delinsCT | 48.0 | 16.89 | Benign/likely benign | Pathogenic |

| KMT2C G972R NM_170606.3:c.2914G>A | 6.1 | 25.3 | NA | Pathogenic |

| KMT2C I4364T NM_170606.3:c.13091T>C | 25.3 | 23.4 | NA | Pathogenic |

| KMT2C R2609Q NM_170606.3:c.7826G>A | 52.1 | 19.54 | Likely benign | Benign |

| KMT2C A779T NM_170606.3:c.2335G>A | 5.4 | 14.75 | NA | Benign |

| KMT2C P1669R NM_170606.3:c.5006C>G | 51.3 | 27.8 | Likely benign | Pathogenic |

| KMT2C T361INM_170606.3:c.1082C>T | 8.5 | 26.6 | NA | Ambiguous |

| KMT2C I1461M NM_170606.3:c.4383T>G | 50.1 | 4.622 | NA | Benign |

| KMT2C H2950R NM_170606.3:c.8849A>G | 28.0 | 0.295 | Uncertain significance | Benign |

| KMT2D R3167Q NM_003482.3:c.9500G>A | 46.7 | 22.2 | Likely benign | Benign |

| KMT2D K1060_V1061delinsNL; NM_03482.3:c.3180_3181delinsTT | 48.8 | 5.382 | Likely benign | Benign |

| KMT2D c9304C>A; p.P3102T | 50.0 | 15.55 | NA | NA |

| KMT2D I5157V M_003482.3:c. 15469A>G | 22.4 | 22.6 | NA | Benign |

| KMT2D Q3863dup NM_003482.3:c.11580_11582dup | 49.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| KMT2D p.A3552Gfs∗3 NM_003482.3:C.10655_10656del | 5.2 | 34 | NA | NA |

| KMT2D P2354S NM_03482.3:c.7060C>T | 37.3 | 16.93 | Benign | Benign |

| KMT2D P3109H NM_003482.3:c9326C>A | 46.5 | 21.6 | Benign | Benign |

| KMT2C G908C NM_170606.3:c.2722G>T | 6.7 | 25.9 | Benign | Pathogenic |

| KMT2D R1835C NM_003482.3:c.5503C>T | 50.1 | 22.7 | Uncertain significance, benign | Benign |

| KMT2C S1931L NM_170606.3:c.5792C>T | 39.5 | 20.5 | Benign | Benign |

| KMT2C T361I NM_1706063:c.1082C>T | 7.1 | 26.6 | NA | Ambiguous |

| KMT2C D599Y NM_170606.3:c. 1795G>T | 45.4 | 12.51 | Likely benign | Benign |

| KMT2C R461S NM_170606.3:c. 13842G>T | 36.2 | 12.9 | NA | Ambiguous |

| KMT2D R2248G NM_003482.3:c. 6742C>G | 46.8 | 13.69 | Benign/likely benign | Benign |

| KMT2C N3505D NM_170606.3:c. 10513A>G | 27.5 | 22.9 | NA | Benign |

| KMT2D S2274L NM_003482.3:c. 6821C>T | 44.3 | 23 | NA | Pathogenic |

| MT variant . | VAF, % . | Phred score . | ClinVar interpretation . | AlphaMissense interpretation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMT2D N2517S NM_00348.3:c.7550A>G | 38.6 | 12.47 | Benign | Benign |

| KMT2D P2717S NM_003482.3:c.8148_delinsCT | 48.0 | 16.89 | Benign/likely benign | Pathogenic |

| KMT2C G972R NM_170606.3:c.2914G>A | 6.1 | 25.3 | NA | Pathogenic |

| KMT2C I4364T NM_170606.3:c.13091T>C | 25.3 | 23.4 | NA | Pathogenic |

| KMT2C R2609Q NM_170606.3:c.7826G>A | 52.1 | 19.54 | Likely benign | Benign |

| KMT2C A779T NM_170606.3:c.2335G>A | 5.4 | 14.75 | NA | Benign |

| KMT2C P1669R NM_170606.3:c.5006C>G | 51.3 | 27.8 | Likely benign | Pathogenic |

| KMT2C T361INM_170606.3:c.1082C>T | 8.5 | 26.6 | NA | Ambiguous |

| KMT2C I1461M NM_170606.3:c.4383T>G | 50.1 | 4.622 | NA | Benign |

| KMT2C H2950R NM_170606.3:c.8849A>G | 28.0 | 0.295 | Uncertain significance | Benign |

| KMT2D R3167Q NM_003482.3:c.9500G>A | 46.7 | 22.2 | Likely benign | Benign |

| KMT2D K1060_V1061delinsNL; NM_03482.3:c.3180_3181delinsTT | 48.8 | 5.382 | Likely benign | Benign |

| KMT2D c9304C>A; p.P3102T | 50.0 | 15.55 | NA | NA |

| KMT2D I5157V M_003482.3:c. 15469A>G | 22.4 | 22.6 | NA | Benign |

| KMT2D Q3863dup NM_003482.3:c.11580_11582dup | 49.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| KMT2D p.A3552Gfs∗3 NM_003482.3:C.10655_10656del | 5.2 | 34 | NA | NA |

| KMT2D P2354S NM_03482.3:c.7060C>T | 37.3 | 16.93 | Benign | Benign |

| KMT2D P3109H NM_003482.3:c9326C>A | 46.5 | 21.6 | Benign | Benign |

| KMT2C G908C NM_170606.3:c.2722G>T | 6.7 | 25.9 | Benign | Pathogenic |

| KMT2D R1835C NM_003482.3:c.5503C>T | 50.1 | 22.7 | Uncertain significance, benign | Benign |

| KMT2C S1931L NM_170606.3:c.5792C>T | 39.5 | 20.5 | Benign | Benign |

| KMT2C T361I NM_1706063:c.1082C>T | 7.1 | 26.6 | NA | Ambiguous |

| KMT2C D599Y NM_170606.3:c. 1795G>T | 45.4 | 12.51 | Likely benign | Benign |

| KMT2C R461S NM_170606.3:c. 13842G>T | 36.2 | 12.9 | NA | Ambiguous |

| KMT2D R2248G NM_003482.3:c. 6742C>G | 46.8 | 13.69 | Benign/likely benign | Benign |

| KMT2C N3505D NM_170606.3:c. 10513A>G | 27.5 | 22.9 | NA | Benign |

| KMT2D S2274L NM_003482.3:c. 6821C>T | 44.3 | 23 | NA | Pathogenic |

NA, not found in the database.

Discussion

The primary drivers of autoimmunity involved in cellular and humoral response are still not well understood. Possible contributing factors include genetic predisposition, environmental factors and, more recently, epigenetic-related mechanisms, which have been implicated in several studies. Maintenance of peripheral B-cell tolerance and prevention of autoimmune disease are affected by epigenetic regulation.18 Epigenetic dysregulation plays a key role in influencing the development of autoimmunity by regulating the functions of immune cells.19 Dysregulated epigenetics were reported in various autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, primary Sjögren syndrome, multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis.20-23 DNA methylation has generally been associated with gene suppression.24 Aberrant DNA methylation in B cells can trigger the generation of autoantibodies and facilitate the onset of autoimmune disease.19 DNA methylation plays an important role in several autoimmune diseases by modifying gene expression profiles.25,26 Alterations in DNA methylation have also been reported in wAIHA, with reduced total DNA methylation level of whole genome in peripheral blood B cells of patients with wAIHA.27

KMT2 lysine methyltransferases methylate the H3K4, a lysine 4 (K4) on histone H3, one of the key amino acid residues on histone proteins that undergoes post-translational modifications, including methylation and acetylation—which play crucial roles in regulating chromatin structure and gene expression. There is a close interaction between KMT2-dependent H3K4 methylation and DNA methylation, highlighting the potential epigenetic stability associated with this histone modification.28 Mutations in MT are seen across all human cancer types, and are recognized as a crucial key for oncogenesis and are associated with cancer treatment resistance.29-31 In addition, histone methylation plays an important role in immune regulation, macrophage polarization,32 and T-cell differentiation.33 In patients with psoriasis, reduction in H3K4 methylation after 3 months of treatment is associated with treatment response.34

In our study, we found a high prevalence of AIC among patients who carry KMT2C and KMT2D SNVs (P = .0005). All MT SNVs were ultrarare in the general population with MAF <0.0003. More than half of the SNVs had Phred score >20, suggesting that most mutations are in the top 1% of the deleterious variants, and 6 were also classified as likely pathogenic by AlphaMissense. Among patients with AIC, patients with MT SNVs tend to have an earlier disease onset than those who did not have MT mutation, although this difference was not statistically significant. We found that in our cohort, patients with MT mutation have a higher proportion of AIC diagnosis. In addition, the median VAF of 42.5% suggests that MT mutations can potentially be associated with germ line predisposition to autoimmune disease, though further confirmation by skin biopsy or buccal swab is required to confirm germ line status. Due to the retrospective design of our study, only peripheral blood or bone marrow samples were available for analysis, limiting our ability to distinguish somatic mutations from germ line variants. Moreover, we observed that patients with MT mutation had a lower IgG level and absolute lymphocyte count, a pattern that aligns with results reported in patients with Kabuki syndrome.7 A patient with Kabuki syndrome and KMT2D mutation who presented with ITP and recurrent infections was found to have common variable immunodeficiency with low lymphocyte count and panhypogammaglobulinemia.35 In pediatric case series of AIC and primary immune deficiency, 10 patients with KMT2D variants had various clinical manifestations.36 One preclinical study in mice showed that KMT2 knockout mice exhibit a significant reduction in CD8+ naïve T cells, leading to a shortened survival by decreased expression of genes related to apoptosis in activated naïve CD8+ T cells.37 However, in our patients, lower IgG level and absolute lymphocyte count were not associated with an inferior clinical outcome, such as an increased rate of infection and hospitalization from infection.

We also observed that the MT+ group had more complement involvement on the direct antiglobulin test (DAT). In wAIHA, up to 50% of cases are positive for complement disposition in the DAT.38 Patients with complement involvement (cAIHA or complement-positive DAT in wAIHA) have worse outcomes in terms of lower hemoglobin levels at diagnosis, increased hospitalization rates, more frequent transfusion requirements, more lines of therapy, and prolonged hospital stay.39,40 However, in our study, the complement involvement did not translate into a lower hemoglobin level and more lines of therapy. The small sample size could be the potential explanation for this observation. Several factors, including acute renal failure, infection, age, ferritin level, and weight were identified as the adverse determinants for AIC outcomes historically.41-44 Identification of an NGS biomarker potentially associated the presence of AIC as well as clinical outcome is a novel contribution of our study.

Although, to our knowledge, this is the first cohort study investigating the relationship between MT mutation and AIC outcomes and clinical characteristics, our study has several limitations. Firstly, as is the nature of a retrospective study, confounding factors and selection bias are inevitable. To mitigate these bias and errors, one senior author meticulously reviewed all the final data. Secondly, the sample size of our study is relatively small, primarily due to the rare prevalence of AIC itself and even less common use of NGS in AIC. Thirdly, due to the fact that the NGS result was obtained from the peripheral blood or bone marrow, it is hard to differentiate somatic and germ line mutations. In addition, there were significant ethnic differences in the prevalence of MT SNVs. Nevertheless, the presence and characteristics of these mutations suggest they may play a relevant role in the underlying pathophysiology of the disease.

There were trends for the MT SNV+ group to have a younger age at disease onset, higher infection rate, hospitalization rate secondary to infection, and a lower CR rate; however, they did not reach statistical significance. This can be attributed to the relatively small sample size. We also noticed the presence of concurrent other gene mutations beyond the scope of this study primarily focused on within this cohort. We did not factor their potential effect into our study due to the infrequent occurrence and uncertain clinical significance. Nevertheless, more studies are required to demonstrate the function of other mutations.

In conclusion, we report for the first time, to our knowledge, that patients with AIC have a high frequency of variants in MT genes. Further prospective studies are needed to better understand and demonstrate the impact of our observations.

Authorship

Contribution: I.M., Z.X., D.C., and H.L. contributed to the study design; I.M., Z.X., D.C., H.L., V.G., J.D.A., N.T., G.M., A.S., R.T., and P.P. contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; I.M. and Z.X. drafted and made revisions to the manuscript; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: I.M. has received research funding from Alexion, Bioverativ, Sanofi, Annexon, Incyte, Kezar, Principia, Rigel, and Novartis; and has served in a consulting role for Alexion, Alpine/Vertex, Apellis, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi, and Recordati. Z.X. has served in a consulting role for Sanofi, and has received travel expenses from Novartis. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Irina Murakhovskaya, Hematology-Oncology, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 3411 Wayne Ave, Ground Floor, Bronx, NY 10467; email: imurakho@montefiore.org.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Irina Murakhovskaya (imurakho@montefiore.org).