Key Points

ANKRD26 VUSs complicate risk assessment in hematologic malignancy and may extend beyond the known pathogenic hot spot.

Unexpected germ line findings from next-generation sequencing highlight the need for clearer guidance in interpreting and managing VUSs.

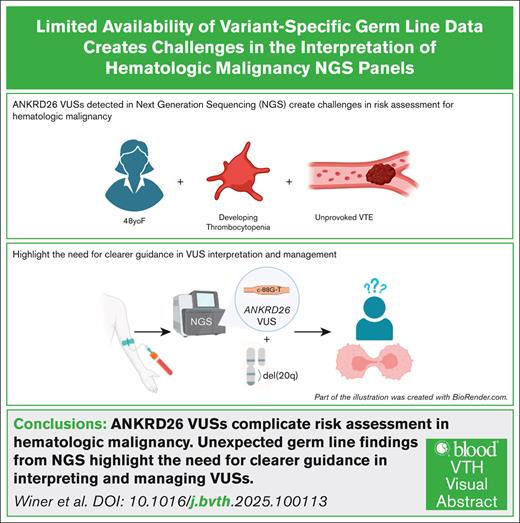

Visual Abstract

ANKRD26-related thrombocytopenia (ANKRD26-RT) is a rare inherited platelet disorder that carries an increased predisposition to hematologic malignancy. We report the case of an unprovoked thrombus in a patient with anemia, who was discovered to have an ANKRD26 germ line variant of uncertain significance (VUS), along with a 20q chromosomal deletion. This patient’s variant lies downstream of the recognized mutational hot spot known to be associated with thrombocytopenia and myeloid neoplasms and, as a VUS, is not definitively diagnostic of ANKRD26-RT. In this case, the del(20q) supports the notion of somatic chromosomal abnormality in the context of unexplained anemia, suggestive of clonal cytopenia of undetermined significance (CCUS). Although 3 known cases of thrombosis have been reported in patients with ANKRD26-RT, there is no known association with hypercoagulability. The role of the ANKRD26 VUS reported in this case vis-à-vis the patient’s hypercoagulability and CCUS remains unclear. This case raises the question of whether hypercoagulability should be added to the expanding phenotypic spectrum of ANKRD26-related disorders, highlights the challenges of interpreting and managing unexpected germ line findings, and underlines the importance of contributing to genetic variant databases to optimize variant calling and recommendations for patients.

Introduction

ANKRD26-related thrombocytopenia (ANKRD26-RT) is a rare inherited platelet disorder characterized by impaired thrombopoiesis and predisposition to hematologic malignancies, most commonly myeloid neoplasms (MNs). The ANKRD26 gene encodes an ankyrin-repeat domain protein–mediating protein-protein interactions.1ANKRD26 expression in megakaryocytes impacts platelet production via regulation of thrombopoietin signaling.2 Germ line mutations most commonly occur in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR), particularly between nucleotides c.-113 and c.-134, disrupting the ability of transcriptional corepressors RUNX1 and FLI1 to bind the ANKRD26 promoter. This results in increased ANKRD26 expression, MAPK signaling, and abnormal platelet development.2 Patients typically exhibit lifelong mild (100 × 109/L to 150 × 109/L) to moderate (50 × 109/L to 99 × 109/L) thrombocytopenia. The lifelong risk of myeloid malignancy is 10% to 15%.3,4

With broader clinical use of next-generation sequencing (NGS), incidental detection of variants of uncertain significance (VUS) in genes associated with inherited syndromes poses diagnostic and clinical challenges, particularly when phenotypic features are incomplete/atypical. In this report, we present a case illustrating the complexity of interpreting an ANKRD26 VUS in the context of additional somatic findings, with implications for diagnosis and risk assessment.

Case presentation

A 48-year-old woman with obesity and without any significant medical history presented with 1 year of nausea and vomiting. Two months before presenting to the clinic, she began taking semaglutide for weight loss; her symptoms were initially attributed to the use of semaglutide, which was subsequently discontinued. Despite cessation, her symptoms persisted, prompting extensive evaluation such as abdominal magnetic resonance imaging which revealed a chronic portal vein thrombus with vascular collateralization and mild splenomegaly. She had no history of thrombosis, cirrhosis, abdominal surgery, or trauma. She was not on oral contraceptives. Age-appropriate cancer screening was up-to-date and unremarkable. FibroScans demonstrated no hepatic fibrosis. In the absence of an identifiable etiology, the patient was referred to hematology for evaluation of a hypercoagulable disorder. Workup revealed new-onset anemia (hemoglobin, 9.4 g/dL [reference range (ref), 11.8-16.0]; mean corpuscular volume [MCV], 81 fL [ref, 81-98]) and a platelet count of 151 × 106/L (ref, 135-371), which decreased from 325 × 106/L 6 years prior (supplemental Table 1). The patient's family history was notable for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in her paternal grandmother and aunt, neither of whom had been tested for thrombophilia.

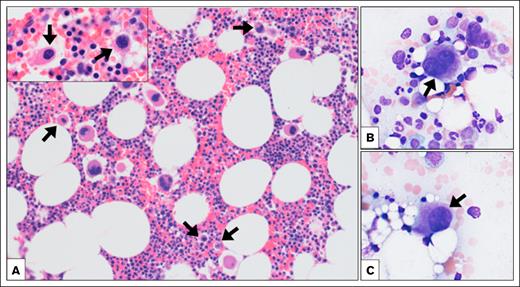

Testing for lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, β2-glycoprotein antibodies, factor V Leiden (FVL), prothrombin G20210A, antithrombin III, and protein C and S activity and flow cytometry for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria were unrevealing. Given thrombosis, anemia, splenomegaly, and the unrevealing workup, a peripheral blood NGS panel was obtained, revealing a single nucleotide variant, c.-88G>T, in the 5′ UTR of ANKRD26 at a variant allele frequency of 47.2% (Table 1). Bone marrow (BM) aspirate and biopsy (Figure 1) demonstrated a normocellular marrow with maturing trilineage hematopoiesis and no increase in blasts. Megakaryocytes displayed atypical forms with small, hypolobated, and hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). Cytogenetic analysis revealed deletion of the long arm of chromosome 20 [del(20q)] in 14 of 20 metaphases (46,XX,del(20)(q11.2q13.3)[14]/46,XX[6]).

NGS reports identifying patient’s ANKRD26 VUS and reported cases of thrombosis in patients with ANKRD26 mutations

| Gene . | Alteration . | Nucleotide change . | Exon . | Allele frequency (%) . | Class . | Zygosity . | Clinical significance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANKRD26 | p.? (5′ UTR variant) | NM_014915.2:c.-88G>T | 1 | 47.21 | Tier 3 | Heterozygous | Uncertain |

| Gene . | Alteration . | Nucleotide change . | Exon . | Allele frequency (%) . | Class . | Zygosity . | Clinical significance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANKRD26 | p.? (5′ UTR variant) | NM_014915.2:c.-88G>T | 1 | 47.21 | Tier 3 | Heterozygous | Uncertain |

| Case . | Mutation . | Age of thrombotic event . | Confounding predisposing factors . | Other known mutations/genetic abnormalities . | Platelet count at time of thrombus discovery . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our patient | c.-88G>T | Late 40s | Obesity, semaglutide use | Chromosomal 20q deletion | 151 × 106/L |

| Noris et al5 | Exact not reported, between -113 to -134. | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 10 × 106/L |

| Guison et al14 | c.-127C>A | 20 | FVL heterozygosity and oral estradiol | FVL heterozygosity | 35 × 106/L |

| Guison et al14 | c.-127C>A | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Case . | Mutation . | Age of thrombotic event . | Confounding predisposing factors . | Other known mutations/genetic abnormalities . | Platelet count at time of thrombus discovery . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our patient | c.-88G>T | Late 40s | Obesity, semaglutide use | Chromosomal 20q deletion | 151 × 106/L |

| Noris et al5 | Exact not reported, between -113 to -134. | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 10 × 106/L |

| Guison et al14 | c.-127C>A | 20 | FVL heterozygosity and oral estradiol | FVL heterozygosity | 35 × 106/L |

| Guison et al14 | c.-127C>A | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

The upper section of the table details the VUS of the patient described in this case report. It depicts the gene alteration, nucleotide change, allele frequency, zygosity, and the clinical significance of the VUS. The lower portion of the table demonstrates the cases of known thrombosis in patients with mutations involving the ANKRD26 gene. It includes (if reported) the mutation, age of thrombotic event, confounding factors, other genetic abnormalities, and platelet count at the time of thrombosis.

BM biopsy findings. The hematoxylin and eosin–stained BM core biopsy (A, original magnification ×200; inset original magnification ×1000) and Wright-stained aspirate smears (B-C, original magnification ×400) showed trilineage hematopoiesis. Megakaryocytes showed a range of morphologies, including atypical small hypolobated forms (arrows).

BM biopsy findings. The hematoxylin and eosin–stained BM core biopsy (A, original magnification ×200; inset original magnification ×1000) and Wright-stained aspirate smears (B-C, original magnification ×400) showed trilineage hematopoiesis. Megakaryocytes showed a range of morphologies, including atypical small hypolobated forms (arrows).

Study design

NGS was performed on BM DNA using hybridization capture-based enrichment with probes from Sophia Genetics (Switzerland). Sequencing was conducted via Illumina NextSeq (San Diego, CA), and data were analyzed through Genosity (Iselin, NJ).

A literature search was conducted using MEDLINE/PubMed and EMBASE to identify cases reporting thrombosis associated with ANKRD26-RT (Table 2). Two of the authors screened all articles.

Search strategy for identifying reports of thrombosis associated with ANKRD26 mutations

| Search number . | Term search . | Studies identified . | Studies selected . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MEDLINE/PubMed | MEDLINE/PubMed following search term was used (ANKRD26[Title/Abstract]) AND (thrombocytopenia[Title/Abstract] OR "Thrombocytopenia"[MeSH Terms]) AND (thrombosis[Title/Abstract] OR thromboembolism[Title/Abstract] OR thrombus[Title/Abstract] OR clot[Title/Abstract] OR "Thrombosis"[MeSH Terms]) | 6 | 3 |

| 2. EMBASE | 'ankrd26':ti,ab AND ('thrombus':ti,ab OR 'clot':ti,ab OR 'thrombosis':ti,ab OR 'thromboembolism':ti,ab) | 11 | 2 |

| Search number . | Term search . | Studies identified . | Studies selected . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MEDLINE/PubMed | MEDLINE/PubMed following search term was used (ANKRD26[Title/Abstract]) AND (thrombocytopenia[Title/Abstract] OR "Thrombocytopenia"[MeSH Terms]) AND (thrombosis[Title/Abstract] OR thromboembolism[Title/Abstract] OR thrombus[Title/Abstract] OR clot[Title/Abstract] OR "Thrombosis"[MeSH Terms]) | 6 | 3 |

| 2. EMBASE | 'ankrd26':ti,ab AND ('thrombus':ti,ab OR 'clot':ti,ab OR 'thrombosis':ti,ab OR 'thromboembolism':ti,ab) | 11 | 2 |

The table details the search criteria used in both MEDLINE/PubMed (row 2) and EMBASE (row 3), respectively. Column 3 demonstrates the number of studies initially identified in the search. Column 4 details the number of relevant articles from each search.

Results and discussion

We present the case of a patient with an unprovoked portal vein thrombus found to have a presumed germ line c.-88G>T variant in the 5′ UTR of the ANKRD26 gene. The 5′ UTR, a segment of messenger RNA upstream of the translation start codon, is noncoding but remains functionally important.1 Termed the hot spot region, mutations in c.-113 to c.-134 impair the ability of transcription factors to repress ANKRD26 in megakaryocytes leading to dysregulated differentiation and risk of clonal evolution.3,5 Among canonical 5′ UTR mutations, known pathogenic variants include c.-113, c.-116, c.-118, c.-119, c.-121, c.-125 to c.-128, c.-134, and c.-140, with c.-128 being most frequently observed.6

The variant detected here has been rarely reported in population databases (gnomAD frequency 6.4e-6) and has been submitted to ClinVar (VariationID:2999897), where it is classified as a VUS.7 As this variant lies downstream of the hot spot region,1 it is unknown whether this variant alters transcription factor binding and/or gene expression. The American College of Medical Genetics has published guidelines for the classification of germ line variants; this variant does not fulfill criteria for classification as either pathogenic or benign and is best classified as a VUS.8

A review of past complete blood counts (CBCs) showed a progressive decrease in platelets over time (supplemental Table 1), although platelets have remained stable since. The megakaryocyte atypia with nuclear hypolobation (Figure 1) noted on BM biopsy is nonspecific but commonly described in patients with pathogenic germ line ANKRD26 mutations.9 In the absence of definitive morphologic dysplasia, the presence of del(20q), and unexplained anemia, the overall findings are best classified as clonal cytopenia of undetermined significance.10

In our case, it is conceivable that the thrombosis was provoked from obesity-related inflammation11 or semaglutide12 despite gastrointestinal symptoms for a year before starting semaglutide use. However, a series of reported thromboses associated with ANKRD26 variants raises the concern that 5′ UTR variants within and outside the hot spot region may increase the risk of thrombosis in addition to increasing the risk of myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia. In patients with documented germ line ANKRD26 mutations, 3 cases of thrombosis have been reported (Table 1). PubMed yielded 6 publications, 3 of which were relevant. The EMBASE search identified 11 articles; 2 were relevant and already captured (supplemental Figure 1). One article assessing thrombosis in the setting of inherited platelet disorders notes 2 cases of DVT in ANKRD26 patients.13 The first case describes 1 ANKRD26 patient, who developed an unprovoked lower extremity DVT.5 The second case details a patient with an ANKRD26 5′ UTR mutation and heterozygous FVL mutation who developed a DVT and pulmonary embolism.14 In the latter, the FVL mutation and a history of oral contraceptive use were potential factors for hypercoagulability that should be considered. Interestingly, the patient’s grandmother (third documented case) carried the ANKRD26 variant, was thrombocytopenic, and suffered from recurrent pulmonary emboli; her FVL status was unclear.14 In our fourth case of thrombosis in a patient with an ANKRD26 VUS, there is a history of unprovoked DVT in the patient’s maternal grandmother and aunt (neither underwent testing for hypercoagulable conditions).

There are attempts to illustrate mechanistic links between ANKRD26 5′ UTR variants and thrombosis. One study utilizing a zebra fish model of ankrd26 5′ UTR mutation-related thrombocytopenia showed that platelets from ankrd26-mutant fish showed enhanced adhesion/aggregation, raising the possibility that ANKRD26 mutations could impact thrombosis.15 It has been suggested that upregulated MAPK activity and thromboxane generation, occurring from dysregulated ANKRD26 expression, could play a role in this process.16 Further studies are necessary to explore this hypothesis prior to establishing the causality of thrombosis from ANKRD26 5′ UTR variants.

Patients with typical pathogenic ANKRD26 variants are considered higher risk for malignancy. The consensus of expert opinions recommends periodic CBCs every 3 to 6 months with repeat BM biopsy considered for cytopenias.1,17-19 However, management of ANKRD26 VUSs with limited variant-specific data is lacking. Current guidelines do not recommend VUSs be used for decision-making while acknowledging certain VUSs may carry increased risk of hematologic malignancy.20 In our case, a del(20q) was incidentally discovered during chromosome analysis. The co-occurrence of this ANKRD26 variant, with a growing body of literature supporting potential pathogenicity, and a somatic del(20q) presents a complex scenario with implications for long-term management. For this patient, we elected to manage her as clonal cytopenia of undetermined significance with biannual CBCs to monitor for cytopenias. This patient’s variant has been added to ClinVar; we will monitor her VUS as ClinVar’s experience with ANKRD26 variants grows.

Although the 5′ UTR hot spot has been characterized, increasing evidence indicates that variants outside this region may be relevant. In a 2022 study analyzing whole-exome-sequencing data from 5561 patients with MN, 436 individuals carried canonical 5′ UTR variants—primarily c.-140C>G (n = 434) and c.-113A>C (n = 2).21 Importantly, 384 patients harbored noncanonical variants: c.-147T>G (n = 1), c.-154C>T (n = 2), and c.-59G>A (n = 381). These findings support hypotheses that ANKRD26-associated predisposition to MNs extends beyond the canonical 5′ UTR hot spot. Our patient was found to carry a presumed germ line ANKRD26 variant at c.-88G>T, located between the known hot spot (c.-113 to c.-134) and the start codon, but outside the classically implicated region. To our knowledge, this variant has not been described in association with hematologic malignancy, nor has it been characterized with functional studies. However, its location within the 5′ UTR and the clinical context in which it was identified suggest it may warrant functional investigation. Additional support for noncanonical pathogenicity comes from a study of patients with acute myeloid leukemia, in which 3 individuals harbored coding region variants (c.3G>A and c.105C>G) producing N-terminally truncated ANKRD26 isoforms, which activated the MAPK/ERK pathway—an effect similarly observed with canonical 5′ UTR mutations.22 Collectively, these findings underscore the need to broaden the mutational landscape considered for ANKRD26-associated disease. Variants such as c.-88G>T, although outside the canonical hot spot, may impact gene regulation/function and should be investigated through functional assays and clinical correlation.

ANKRD26-RT is an inherited disorder associated with increased risk of MN. Although surveillance guidelines exist for pathogenic ANKRD26 variants, no clear recommendations exist for VUSs. This case underscores the ambiguity that VUSs introduce, highlighting the need for robust frameworks to guide interpretation. Reporting of VUSs and detailed clinical and familial phenotyping is critical to improve risk stratification and variant reclassification.

Authorship

Contribution: A.J.W. drafted the original case report, created the supplemental tables, the visual abstract, and manuscript revisions; E.F.M. revised the case report, curated data, interpreted the bone marrow biopsy, and provided the biopsy figure; A.G.B. revised the case report, curated data, and supervised the finalization of the manuscript; M.R.S. revised the case report, curated data, and supervised the finalization of the manuscript; and A.K. revised the case report, curated data, and supervised the finalization of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ashwin Kishtagari, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 1211 Medical Center Dr, 3923 TVC, Nashville, TN 37232; email: ashwin.kishtagari@vumc.org.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Ashwin Kishtagari (ashwin.kishtagari@vumc.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.