Key Points

Syk inhibition with R788 worsened anemia and neutropenia in Townes sickle mice; nontoxic doses did not affect NETosis.

R788 treatment reduced splenomegaly in Townes sickle mice but suppressed hematopoiesis leading to neutropenia and worsened anemia.

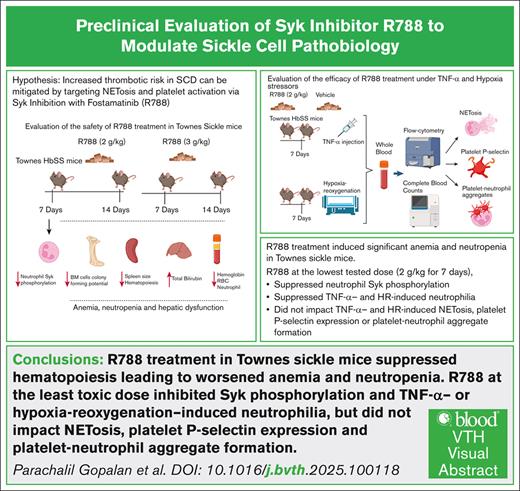

Visual Abstract

Vaso-occlusive crises, thrombosis, inflammation, and immune dysregulation contribute to organ damage and poor outcomes in sickle cell disease (SCD). Because neutrophils and dysregulated extracellular trap formation (NETosis) contribute to sickle pathophysiology, and the spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) signaling pathway is a key driver of NETosis, we investigated the effect of targeting Syk with fostamatinib (R788). Specifically, we studied the effect of a selective Syk inhibitor, R788, on hematologic and biochemical parameters, NETosis, platelet P-selectin expression, and platelet-neutrophil aggregate formation in Townes sickle mice at baseline and after exposure to pathophysiological stressors (tumor necrosis factor α [TNF-α] and hypoxia-reoxygenation). Our results showed that at baseline R788 impaired hematopoiesis, and worsened anemia and neutropenia in sickle mice. Additionally, R788 at nontoxic doses had little, if any, effect on NETosis and platelet activation induced by TNF-α or hypoxia-reoxygenation. Severe anemia and neutropenia induced by R788 in the sickle mouse model suggests that concomitant use of Syk inhibitors with hydroxyurea in patients with SCD should be approached cautiously. Further research is required to clarify the benefits and risks of selective Syk inhibition in SCD and other hemolytic conditions exhibiting stress hematopoiesis.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD), the most prevalent inherited anemia worldwide, is caused by a single-nucleotide substitution in the β-globin gene, leading to the production of sickle hemoglobin (HbS). When deoxygenated, HbS polymerizes causing red blood cells (RBC) to “sickle,” leading to microvascular occlusion and hemolysis.1,2 Repeated cycles of red cell sickling and unsickling promotes adhesive interactions between sickled RBC, endothelial cells, neutrophils, and platelets. These interactions cause microvascular obstruction3-5 and painful vaso-occlusive crises (VOC), and trigger ischemia-reperfusion injury, exacerbating inflammation and ultimately resulting in organ damage.3,6,7

Neutrophilia in patients with SCD predicts disease severity8-11 and sickle neutrophils display dysregulated activity.9,12-14 Moreover, damage-associated molecular patterns in the vasculature, such as free HbS and cell-free DNA,15-18 activate neutrophils to release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).18,19 NET formation (NETosis) is a critical neutrophil defense that limits the spread of infectious organisms. However, NET components also serve as a scaffold for coagulation factors, promoting vascular fibrin deposition, and intravascular thrombosis.20-22 NET components, including myeloperoxidase and citrullinated histones, further exacerbate NETosis, creating a vicious cycle that worsens vascular injury.23,24 Tissue hypoxia that accompanies VOC in SCD by stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factor 1α can exacerbate NETosis during tissue reperfusion.25-27 Finally, P-selectin on activated platelets leads to enhanced formation of platelet-neutrophil aggregates (PNA), further inciting NETosis, vascular injury, and thrombosis.28,29

Approaches targeting neutrophil number and/or function have the potential to mitigate SCD complications because in patients with SCD, neutrophils are activated and exhibit dysregulated NETosis, thereby contributing to sickle pathobiology.14 One such approach is inhibition of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), a cytoplasmic nonreceptor tyrosine kinase which, when phosphorylated, activates several important cellular effector functions including NETosis,30-33 platelet activation,34,35 and heterocellular aggregate formation.36 Syk phosphorylation (p-Syk) can be selectively inhibited by fostamatinib (R788), a prodrug metabolized by intestinal phosphatases to its active metabolite, R406.37,38 In murine models, R788 treatment reduced ischemia-reperfusion injury–associated NETosis,39,40 and neutrophil-mediated acute lung injury.41 We hypothesized that inhibiting p-Syk with R788 would attenuate NETosis, platelet activation, and formation of PNA and ultimately ameliorate SCD complications. To test this hypothesis, we pretreated Townes sickle mice (HbSS),42 with R788 and challenged them with intraperitoneal tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) injection18 or hypoxia-reoxygenation (HR) exposure,43,44 to mimic sickle thromboinflammatory and ischemia-reperfusion pathophysiology, respectively.

Materials and methods

Sickle cell mice

Animal studies were approved by the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center animal care and use committee and adhered to the guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (National Institutes of Health institutional review board approval number: DPM23-03). We examined the Townes sickle mouse model (HbSS), genetically engineered to express human HbSS and genetic matched controls expressing human HbAA, both developed on a C57BL/6;129 background.42,45 Breeding and genotyping were conducted as previously described.46,47 All experimental groups included age-matched (18-24 weeks) male and female HbSS and HbAA mice.

Experimental procedures

Administration and safety evaluation of R788

HbSS mice and HbAA mice were treated with R788 chow or vehicle chow (D11112201, open standard diet with 15 kcal percent fat; supplied by Rigel Pharmaceuticals) ad libitum. Safety was assessed by monitoring adverse events, complete blood counts, and liver and renal function parameters after treatment with R788 at 2 g/kg48 for 7 or 14 days and 3 g/kg49,50 for 7 or 14 days. At the end of treatment, blood was collected from anesthetized mice by cardiac puncture in heparin-coated syringes. Then, mice were euthanized, and the spleens were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histopathology.

Modeling sickle thromboinflammation and VOC with TNF-α and HR

Mice were treated with R788 and then exposed to pathophysiological stressors to assess the effects of selective Syk inhibition. To model thromboinflammation, HbSS and HbAA mice were injected intraperitoneally with recombinant murine TNF-α (0.5 μg),18 after R788 treatment. Mice were euthanized 5 hours after TNF-α injection, and blood and spleens were collected as described earlier. To model VOC, HbSS and HbAA mice were exposed to HR challenge as described previously,43,44 after R788 treatment. Mice were euthanized at the end of the HR experiments, and blood and spleens were collected.

Study end points

Splenic weight and histopathology, complete blood counts, and metabolic parameters were obtained using standard methods.51-53 To assess the impact of Syk inhibition on the clonogenic potential of hematopoietic progenitor cells, a MethoCult colony-forming unit (CFU) assay was performed using MethoCult M3434 (Stemcell Technologies) with bone marrow (BM)–derived cells.54 We assessed the total number of CFUs, including erythroid burst-forming unit (BFU-E), granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (CFU-GM), and granulocyte, erythroid, monocyte, megakaryocyte progenitors (CFU-GEMM), as a general measure of erythroid and myeloid hematopoiesis. Plasma R406 level (the active metabolite of R788) was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry,55 and R788-mediated inhibition of neutrophil p-Syk was assessed by flow cytometry.56 Effect of Syk inhibition on pathophysiological stress response to TNF-α injection or HR challenge was assessed by evaluating NETosis,57 platelet surface P-selectin expression,58,59 and circulating PNA,60,61 in anticoagulated whole blood using flow cytometry. Experimental details are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

The effect of treatment (R788 or vehicle) on both genotypes (HbAA and HbSS) was analyzed using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Dunnett test, or 2-way ANOVA, with false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons.62 Data are shown as mean and standard deviation. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). P values ≤.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

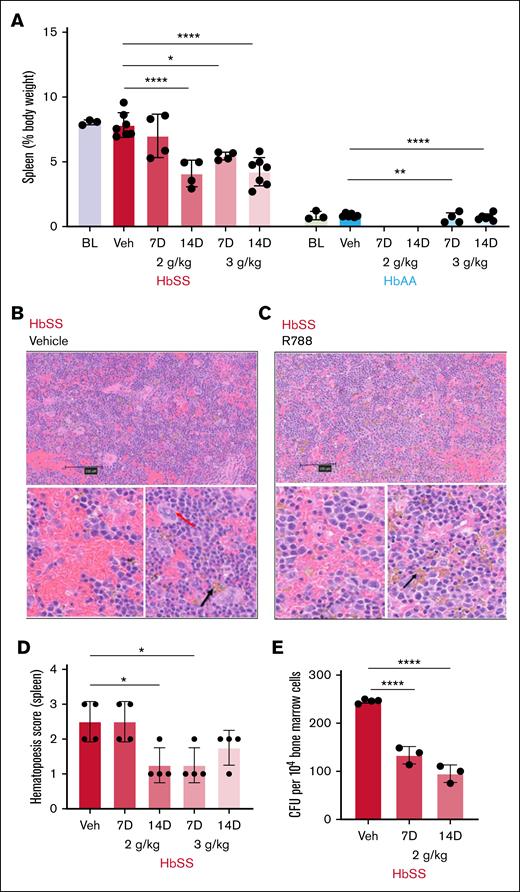

R788 reduced splenomegaly and splenic hematopoietic foci

Unlike humans with SCD who exhibit splenic atrophy, HbSS mice display massive splenomegaly compared with HbAA mice, due to extramedullary hematopoiesis that compensates for severe hemolytic anemia (percentage body weight: spleen, 8% ± 0.1% [HbSS] vs 0.8% ± 0.3% [HbAA]; P < .0001).63 R788 treatment, except for the 2 g/kg 7-day regimen, reduced splenomegaly by half in HbSS mice compared with vehicle treatment (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1). A 2-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects (P < .0001) of both genotype and treatment on spleen weight (Table 1). Histopathological examination of R788-treated HbSS mice revealed reduced splenic red cell congestion, increased hemosiderin deposition in splenic macrophages (Figure 1B-C), and reduced number of splenic hematopoietic foci evaluated by the extent of megakaryocytes presence (Figure 1D) compared with vehicle treatment.64

Effects of R788 treatment on extramedullary hematopoiesis. (A) Impact of R788 treatment on spleen weights expressed as percentage body weight in HbSS and HbAA mice after treatment with R788 at 2 g/kg and 3 g/kg for 7 and 14 days (gaps represent missing/not available data). (B) Representative low magnification (scale bar, 100 μm) cross-section image of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained splenic sections from vehicle-treated HbSS mouse and (below) under high magnification (scale bar, 10 μm) shows splenic engorgement and foci of hematopoietic cells (red arrow, evaluated on the basis of extent of megakaryocytes present) representing extramedullary hematopoiesis. (C) H&E-stained splenic sections of R788-treated (3 g/kg for 14 days) HbSS mice at low magnification, and at high magnification (below) showing reduction in splenic engorgement, reduced hematopoietic foci, and increased iron pigment deposition (black arrow). (D) Splenic hematopoietic score (erythroid precursor colonies with megakaryocytes: 0, absent; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe; and 4, abundant) after vehicle or R788 treatment in HbSS mice. (E) CFU count from 104 cultured BM cells in methylcellulose-based Media (MethoCult GF M3434) from vehicle- and R788-treated (2 g/kg for 7 and 14 days) HbSS mice. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with each data point representing a single animal. Statistical comparisons between treatment groups and the vehicle group were performed using 1-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett test, or 2-way ANOVA with false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons. Significance set as follows: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HbSS, red; HbAA, blue. BL, baseline; Veh, vehicle-treated.

Effects of R788 treatment on extramedullary hematopoiesis. (A) Impact of R788 treatment on spleen weights expressed as percentage body weight in HbSS and HbAA mice after treatment with R788 at 2 g/kg and 3 g/kg for 7 and 14 days (gaps represent missing/not available data). (B) Representative low magnification (scale bar, 100 μm) cross-section image of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained splenic sections from vehicle-treated HbSS mouse and (below) under high magnification (scale bar, 10 μm) shows splenic engorgement and foci of hematopoietic cells (red arrow, evaluated on the basis of extent of megakaryocytes present) representing extramedullary hematopoiesis. (C) H&E-stained splenic sections of R788-treated (3 g/kg for 14 days) HbSS mice at low magnification, and at high magnification (below) showing reduction in splenic engorgement, reduced hematopoietic foci, and increased iron pigment deposition (black arrow). (D) Splenic hematopoietic score (erythroid precursor colonies with megakaryocytes: 0, absent; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe; and 4, abundant) after vehicle or R788 treatment in HbSS mice. (E) CFU count from 104 cultured BM cells in methylcellulose-based Media (MethoCult GF M3434) from vehicle- and R788-treated (2 g/kg for 7 and 14 days) HbSS mice. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with each data point representing a single animal. Statistical comparisons between treatment groups and the vehicle group were performed using 1-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett test, or 2-way ANOVA with false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons. Significance set as follows: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HbSS, red; HbAA, blue. BL, baseline; Veh, vehicle-treated.

Spleen weight, hematology, and biochemical parameters in HbSS and HbAA mice

| Parameter (mean ± SD) . | HbSS . | HbAA . | ANOVA statistics . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline . | Vehicle . | R788 2 g/kg . | R788 3 g/kg . | Baseline . | Vehicle . | R788 3 g/kg . | Genotype . | Treatment . | ||||

| (n = 3) . | 7 to 14 days (n = 10) . | 7 Days (n = 4) . | 14 Days (n = 4) . | 7 Days (n = 4) . | 14 Days (n = 7) . | (n = 3) . | 7 to 14 days (n = 10) . | 7 Days (n = 4) . | 14 Days (n = 5) . | P value . | P value . | |

| Spleen, % body weight | 8 ± 0.1 | 7.8 ± 0.7 | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 4.0 ± 1.0∗∗∗∗ | 5.9 ± 1.1∗ | 4.2 ± 1.1∗∗∗∗ | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.88 ± 0.19 | 0.66 ± 0.40∗∗ | 0.72 ± 0.25∗∗∗∗ | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Hb, g/dL | 8.3 ± 0.45 | 8.8 ± 1.0 | 7.1 ± 0.9 | 6.9 ± 1.7 | 5.7 ± 2.4∗ | 5.5 ± 1.6∗∗∗∗ | 11.6 ± 0.2 | 10.5 ± 1.2 | 9.6 ± 1.6∗ | 8.9 ± 1.1∗∗∗∗ | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| RBC count, ×106/μL | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.8∗∗∗∗ | 4.4 ± 1.4∗∗∗ | 3.3 ± 1.3∗∗∗∗ | 3.3 ± 1.0∗∗∗∗ | 11.0 ± 0.3 | 10.7 ±0.4 | 8.6 ± 0.7∗∗∗∗ | 7.6 ± 1.3∗∗∗∗ | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| WBC count, ×103/μL | 30.5 ± 3.6 | 32.7 ± 10.4 | 30.6 ± 3.3 | 15.0 ± 1.4∗∗∗ | 28.6 ± 11.6 | 15.3 ± 7.2∗∗∗ | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 6.4 ± 2.9 | 4.8 ± 1.9 | 5.0 ± 1.28∗∗∗ | .0005 | <.0001 |

| ANC, ×103/μL | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 1.0∗∗ | 1.4 ± 0.1∗∗ | 1.4 ± 1.0∗∗∗∗ | 0.87 ± 0.16 | 1.11 ± 0.59 | 0.87 ± 0.42∗∗ | 0.66 ± 0.22∗∗∗∗ | <.0001 | .0001 |

| Platelets, ×103/μL | 794 ± 62 | 798 ± 190 | 876 ± 196 | 585 ± 208 | 1528 ± 834∗∗∗ | 853 ± 362∗ | 981 ± 43 | 928 ± 138 | 1402 ± 596∗∗∗ | 1303 ± 115∗ | .0039 | .0067 |

| ALT, U/Lǂ | 114 ± 25 | 134 ± 87 | 67 ± 19 | 93 ± 47 | 57 ± 8 | 65 ± 11 | 39 ± 6 | 38 ± 5 | 99 ± 70 | 38 ± 3 | .0002 | .1647 |

| AST, U/Lǂ | 128 ± 25 | 112 ± 30 | 111 ± 38 | 115 ± 27 | 95 ± 8 | 103 ± 19 | 76.6 ± 6.1 | 109 ± 21 | 129 ± 51 | 93 ± 50 | .08872 | .6798 |

| Bilirubin (total), mg/dLǂ | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.9∗∗ | 3.9 ± 1.5∗∗ | 4.1 ± 2.5∗∗ | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 0.1 ± 0 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.52 ± 0.44∗∗ | 0.28 ± 0.21 | <.0001 | .0021 |

| Free Hb in plasma, mg/dL§ | NA | 64.6 ± 12.1 | 78.3 ± 26.3 | 79.7 ± 34.5 | 108.1 ± 37.7∗∗ | 75.3 ± 21.6 | NA | 38.9 ± 12.9 | 86.0 ± 19.4∗∗ | 45.1 ± 9.6 | .0165 | .0165 |

| LDH, U/Lǂ | 293 ± 23 | 356 ± 115 | 493 ± 308 | 346 ± 72 | 338 ± 26 | 373 ± 86 | 388 ± 76 | 346 ± 70 | 487 ± 88 | 266 ± 75 | .8059 | .2076 |

| BUNǂ | 17.9 ± 2.1 | 13.6 ± 3.0 | 21.9 ± 5.18 | 22.2 ± 5.8∗ | 30.5 ± 8.3∗∗∗ | 19 ± 2.8∗ | 16.6 ± 3.4 | 14.3 ± 3.6 | 16.5 ± 4.4∗∗∗ | 15.7 ± 4.2 | .0221 | .0082 |

| Plasma R406, ng/mL§ | NA | ND | 533 ± 368 | 1424 ± 1227 | 2275 ± 2094 | 781 ± 415 | NA | ND | 1804 ± 937 | 1477 ± 2004 | .4531 | .2272 |

| Parameter (mean ± SD) . | HbSS . | HbAA . | ANOVA statistics . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline . | Vehicle . | R788 2 g/kg . | R788 3 g/kg . | Baseline . | Vehicle . | R788 3 g/kg . | Genotype . | Treatment . | ||||

| (n = 3) . | 7 to 14 days (n = 10) . | 7 Days (n = 4) . | 14 Days (n = 4) . | 7 Days (n = 4) . | 14 Days (n = 7) . | (n = 3) . | 7 to 14 days (n = 10) . | 7 Days (n = 4) . | 14 Days (n = 5) . | P value . | P value . | |

| Spleen, % body weight | 8 ± 0.1 | 7.8 ± 0.7 | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 4.0 ± 1.0∗∗∗∗ | 5.9 ± 1.1∗ | 4.2 ± 1.1∗∗∗∗ | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.88 ± 0.19 | 0.66 ± 0.40∗∗ | 0.72 ± 0.25∗∗∗∗ | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Hb, g/dL | 8.3 ± 0.45 | 8.8 ± 1.0 | 7.1 ± 0.9 | 6.9 ± 1.7 | 5.7 ± 2.4∗ | 5.5 ± 1.6∗∗∗∗ | 11.6 ± 0.2 | 10.5 ± 1.2 | 9.6 ± 1.6∗ | 8.9 ± 1.1∗∗∗∗ | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| RBC count, ×106/μL | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.8∗∗∗∗ | 4.4 ± 1.4∗∗∗ | 3.3 ± 1.3∗∗∗∗ | 3.3 ± 1.0∗∗∗∗ | 11.0 ± 0.3 | 10.7 ±0.4 | 8.6 ± 0.7∗∗∗∗ | 7.6 ± 1.3∗∗∗∗ | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| WBC count, ×103/μL | 30.5 ± 3.6 | 32.7 ± 10.4 | 30.6 ± 3.3 | 15.0 ± 1.4∗∗∗ | 28.6 ± 11.6 | 15.3 ± 7.2∗∗∗ | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 6.4 ± 2.9 | 4.8 ± 1.9 | 5.0 ± 1.28∗∗∗ | .0005 | <.0001 |

| ANC, ×103/μL | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 1.0∗∗ | 1.4 ± 0.1∗∗ | 1.4 ± 1.0∗∗∗∗ | 0.87 ± 0.16 | 1.11 ± 0.59 | 0.87 ± 0.42∗∗ | 0.66 ± 0.22∗∗∗∗ | <.0001 | .0001 |

| Platelets, ×103/μL | 794 ± 62 | 798 ± 190 | 876 ± 196 | 585 ± 208 | 1528 ± 834∗∗∗ | 853 ± 362∗ | 981 ± 43 | 928 ± 138 | 1402 ± 596∗∗∗ | 1303 ± 115∗ | .0039 | .0067 |

| ALT, U/Lǂ | 114 ± 25 | 134 ± 87 | 67 ± 19 | 93 ± 47 | 57 ± 8 | 65 ± 11 | 39 ± 6 | 38 ± 5 | 99 ± 70 | 38 ± 3 | .0002 | .1647 |

| AST, U/Lǂ | 128 ± 25 | 112 ± 30 | 111 ± 38 | 115 ± 27 | 95 ± 8 | 103 ± 19 | 76.6 ± 6.1 | 109 ± 21 | 129 ± 51 | 93 ± 50 | .08872 | .6798 |

| Bilirubin (total), mg/dLǂ | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.9∗∗ | 3.9 ± 1.5∗∗ | 4.1 ± 2.5∗∗ | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 0.1 ± 0 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.52 ± 0.44∗∗ | 0.28 ± 0.21 | <.0001 | .0021 |

| Free Hb in plasma, mg/dL§ | NA | 64.6 ± 12.1 | 78.3 ± 26.3 | 79.7 ± 34.5 | 108.1 ± 37.7∗∗ | 75.3 ± 21.6 | NA | 38.9 ± 12.9 | 86.0 ± 19.4∗∗ | 45.1 ± 9.6 | .0165 | .0165 |

| LDH, U/Lǂ | 293 ± 23 | 356 ± 115 | 493 ± 308 | 346 ± 72 | 338 ± 26 | 373 ± 86 | 388 ± 76 | 346 ± 70 | 487 ± 88 | 266 ± 75 | .8059 | .2076 |

| BUNǂ | 17.9 ± 2.1 | 13.6 ± 3.0 | 21.9 ± 5.18 | 22.2 ± 5.8∗ | 30.5 ± 8.3∗∗∗ | 19 ± 2.8∗ | 16.6 ± 3.4 | 14.3 ± 3.6 | 16.5 ± 4.4∗∗∗ | 15.7 ± 4.2 | .0221 | .0082 |

| Plasma R406, ng/mL§ | NA | ND | 533 ± 368 | 1424 ± 1227 | 2275 ± 2094 | 781 ± 415 | NA | ND | 1804 ± 937 | 1477 ± 2004 | .4531 | .2272 |

The table shows post hoc multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Krieger-Yekutieli procedure after 2-way ANOVA. Statistical significance is set as follows: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

ALT, alanine amino transaminase; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; AST, aspartate alanine transaminase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NA, not applicable; ND, not detected; SD, standard deviation.

Values derived from testing 4 to 6 mice.

Vales derived from testing 3 to 4 mice. ǂ and § Represents the number of mice tested in each respective experiment.

R788 impairs colony-forming potential of BM hematopoietic precursors

We evaluated total CFUs, including BFU-E, CFU-GM, and CFU-GEMM, as a functional readout of erythroid and myeloid progenitor activity. BM-derived hematopoietic precursors from R788-treated HbSS mice when cultured in vitro in MethoCult M3134 medium showed a significant reduction in the number of CFUs compared with vehicle-treated animals (total CFUs per 104 BM cells: vehicle, 245 ± 4; R788 2 g/kg, 133 ± 18 [7 days] and 95 ± 18 [14 days]; P < .0001; Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 2). There was an overall reduction in CFUs of BFU-E, CFU-GEMM, and CFU-GM in R788-treated mice compared with vehicle treatment.

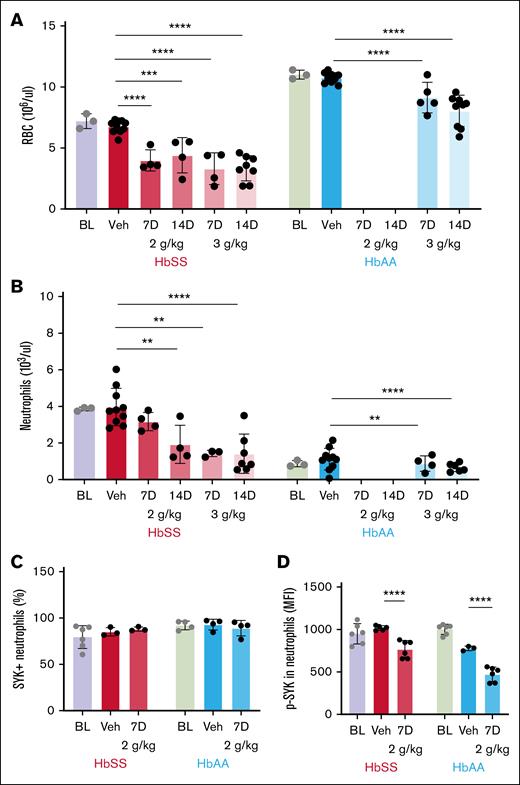

R788 treatment worsened anemia and induced neutropenia

Similar to patients with SCD, HbSS mice have lower RBC counts and Hb than HbAA (RBC count: HbSS, 7.2 × 106 ± 0.6 × 106/μL, vs HbAA, 11.0 × 106 ± 0.3 × 106/μL; P < .0001; Table 1). Treatment with R788 in HbSS mice further reduced RBC count and Hb by half compared with vehicle treatment (RBC count: vehicle, 6.7 × 106 ± 0.5 × 106/μL; R788 2 g/kg, 3.9 × 106 ± 0.8 × 106/μL [7 days] and 4.4 × 106 ± 1.4 × 106/μL [14 days]; R788 3 g/kg, 3.3 × 106 ± 1.3 × 106/μL [7 days] and 3.3 × 106 ± 1.0 × 106/μL [14 days]; P < .0001). After R788 treatment, HbAA mice also exhibited significant reductions in RBC count and Hb compared with vehicle treatment (RBC count: vehicle, 10.7 × 106 ± 0.4 × 106/μL; R788 3 g/kg, 8.6 × 106 ± 0.7 × 106/μL [7 days] and 7.6 × 106 ± 1.3 × 106/μL [14 days]; P < .0001; Figure 2A).

Effect of Syk inhibition with R788 on peripheral blood counts. (A) R788 at all doses and durations (2 g/kg and 3 g/kg for 7 and 14 days) significantly reduced RBC counts in HbSS mice and HbAA mice compared with vehicle treatment. (B) Circulating peripheral blood neutrophil numbers were significantly reduced by R88-treatment in HbSS (except for the 2 g/kg 7 days treatment) and HbAA mice. (C) Percentage of neutrophils expressing Syk protein was not affected by R788 treatment at 2 g/kg for 7 days in HbSS and HbAA mice. (D) p-Syk (MFI) in peripheral blood neutrophils were significantly reduced in HbSS and HbAA mice after treatment with R788 at 2 g/kg for 7 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each data point representing a single animal. Treatment groups were compared with the vehicle group using a 2-way ANOVA, with FDR correction for multiple comparisons. Significance levels: ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HbSS, red; HbAA, blue. BL, baseline; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; Veh, vehicle-treated.

Effect of Syk inhibition with R788 on peripheral blood counts. (A) R788 at all doses and durations (2 g/kg and 3 g/kg for 7 and 14 days) significantly reduced RBC counts in HbSS mice and HbAA mice compared with vehicle treatment. (B) Circulating peripheral blood neutrophil numbers were significantly reduced by R88-treatment in HbSS (except for the 2 g/kg 7 days treatment) and HbAA mice. (C) Percentage of neutrophils expressing Syk protein was not affected by R788 treatment at 2 g/kg for 7 days in HbSS and HbAA mice. (D) p-Syk (MFI) in peripheral blood neutrophils were significantly reduced in HbSS and HbAA mice after treatment with R788 at 2 g/kg for 7 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each data point representing a single animal. Treatment groups were compared with the vehicle group using a 2-way ANOVA, with FDR correction for multiple comparisons. Significance levels: ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HbSS, red; HbAA, blue. BL, baseline; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; Veh, vehicle-treated.

As in patients with SCD,10,11 HbSS mice exhibit leukocytosis (white blood cell count: HbSS, 30.5 × 103 ± 3.6 × 103/μL vs HbAA, 4.6 × 103 ± 1.1 × 103/μL; P < .0001) and nearly fourfold higher neutrophil counts than HbAA controls (neutrophil count: HbSS, 3.8 × 103 ± 0.1 × 103/μL vs HbAA, 0.87 × 103 ± 0.16 × 103/μL; P < .0001). R788 treatment reduced neutrophil counts by more than half in HbSS mice compared with vehicle treatment at all doses except for the 2 g/kg for 7 days dose (neutrophil count: vehicle, 3.9 × 103 ± 1.0 × 103/μL; R788 2 g/kg, 3.1 × 103 ± 0.4 × 103/μL [7 days] and 1.9 × 103 ± 1.0 × 103/μL [14 days]; R788 3 g/kg, 1.4 × 103 ± 0.1 × 103/μL [7 days] and 1.4 × 103 ± 1.0 × 103/μL [14 days]; P < .0001). Interestingly, HbAA mice also showed significant reductions in neutrophil counts after treatment with R788 compared with vehicle (Table 1; Figure 2B). Platelet counts were significantly lower in HbSS mice at baseline than in HbAA mice (platelet count: HbSS, 794 × 103 ± 62 × 103/μL vs HbAA, 981 × 103 ± 43 × 103/μL; P = .0039). R788 treatment increased platelet counts significantly in HbSS mice at both 3 g/kg doses for 7 and 14 days compared with vehicle treatment. R788 treatment in HbAA mice also significantly increased platelet counts compared with vehicle treatment (Table 1). Collectively, these data indicate that Syk inhibition with R788 in HbSS mice suppressed hematopoiesis leading to significant worsening of anemia and induction of neutropenia, an effect also observed in HbAA animals.

R788 treatment increases total plasma bilirubin levels without inducing hemolysis

At baseline, liver enzyme alanine aminotransferase was elevated in HbSS mice compared with HbAA controls (Table 1). Both alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase were not affected by R788 treatment in HbSS and HbAA mice (Table 1). Baseline plasma total bilirubin levels were elevated in HbSS mice compared with HbAA mice, reflecting ongoing hemolysis (total bilirubin: HbSS, 1.1 ± 0.1 mg/dL vs HbAA, 0.1 ± 0 mg/dL; P < .0001). Treatment with R788 except for 3 g/kg for 14 days increased total bilirubin in HbSS and HbAA mice compared with vehicle treatment (Table 1). As expected, plasma free Hb, reflecting intravascular hemolysis,65 was significantly elevated in vehicle-treated HbSS mice compared with HbAA mice (free Hb: HbSS, 64.6 ± 12.1 mg/dL vs HbAA, 38.9 ± 12.9 mg/dL; P = .03). Plasma free Hb levels and blood urea nitrogen were elevated in HbSS and HbAA mice after treatment with 3 g/kg R788 for 7 days. Lactate dehydrogenase levels were similar in R788- and vehicle-treated HbSS mice (Table 1). Taken together, these results suggest that Syk inhibition with R788 induced mild hepatic dysfunction in HbSS mice without exacerbating hemolysis.

R788 treatment yielded detectable plasma R406 and inhibited neutrophil p-Syk

Consumption of R788-containing chow yielded detectable R406 levels in plasma of HbSS mice that were similar across treatment doses and durations (R406 concentration: R788 2 g/kg, 1.1 ± 0.7 μmol [7 days] and 3.0 ± 2.6 μmol [14 days]; R788 3 g/kg, 4.8 ± 4.4 μmol [7 days] and 1.1 ± 0.7 μmol [14 days]; P = .28). Plasma R406 levels in HbAA mice were similar to those in HbSS mice, indicating similar drug exposure in both genotypes (Table 1). As expected, R406 was undetectable in vehicle-treated mice. Syk protein expression (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 3) in peripheral blood neutrophils from HbSS and HbAA mice were similar although the BM showed higher percentage of Syk-expressing neutrophils than the peripheral blood (Syk+ neutrophils: HbSS, 97.4% ± 2.0% [BM] vs 79.3% ± 12.3% [blood]; P = .005). Baseline p-Syk was significantly lower in HbSS than HbAA mice (p-Syk mean fluorescence intensity: HbSS, 949 ± 120 vs HbAA, 1001 ± 60; P = .001; Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 4). R788-treated mice (2 g/kg, 7 days) exhibited significantly reduced peripheral blood neutrophil p-Syk levels compared with vehicle treatment (p-Syk mean fluorescence intensity, HbSS [vehicle, 1018 ± 26; R788, 767 ± 102] and HbAA [vehicle, 776 ± 26 vs R788, 471 ± 85]; P < .0001; Figure 2D).

R788 treatment at maximum tolerable doses inhibited neutrophilia but did not suppress TNF-α or HR-induced NETosis

Because all doses of R788 except for 2 g/kg for 7 days were associated with significant hematologic toxicity but effectively inhibited p-Syk, we used the 2 g/kg for 7 days before conducting pathophysiologic challenge experiments with TNF-α and HR. TNF-α injection in vehicle-treated HbSS mice significantly increased neutrophil counts above baseline (neutrophil count: HbSS baseline, 3.8 × 103 ± 0.1 × 103/μL; TNF-α induced, 5.5 × 103 ± 1.8 × 103/μL; P = .01) and R788 treatment (2 g/kg for 7 days) inhibited neutrophilia by half compared with vehicle (neutrophil count: HbSS vehicle, 5.5 × 103 ± 1.8 × 103/μL; R788 2 g/kg [7 days], 2.0 × 103 ± 0.4 × 103/μL; P < .0001). HbAA mice also exhibited TNF-α–induced neutrophilia (neutrophil count: baseline, 0.8 × 103 ± 0.1 × 103/μL; TNF-α induced, 1.6 × 103 ± 0.1 × 103/μL; P = .01) and R788 treatment inhibited this neutrophilia significantly compared with vehicle treatment (neutrophil count: HbAA, vehicle, 1.6 × 103 ± 0.1 × 103/μL; R788 2 g/kg [7 days], 1.0 × 103 ± 0.4 × 103/μL; P < .0001; Figure 3A). HR in vehicle-treated HbSS mice induced a modest nonsignificant increase in neutrophil count compared with baseline (neutrophil count: baseline, 3.7 × 103 ± 0.7 × 103/μL vs HR induced, 5.3 × 103 ± 2.3 × 103/μL; P = .3). R788 treatment inhibited this neutrophilia by more than half compared with vehicle (neutrophil count: vehicle, 5.3 × 103 ± 2.3 × 103/μL; R788 2 g/kg [7 days], 1.8 ± 0.2; P = .0008). HbAA mice did not demonstrate HR-induced neutrophilia (Figure 3B).

Impact of R788 on neutrophil counts and NETosis induced by TNF-α and HR. (A) Bar graphs showing the effect of R788 on TNF-α–induced neutrophilia in HbSS and HbAA mice. (B) Effect of R788 on HR-induced neutrophilia in HbSS and HbAA mice. (C) Treatment effect of 2 g/kg of R788 for 7 days on TNF-α–induced NETosis (neutrophils [percent] expressing extracellular DNA, myeloperoxidase, and tricitrullinated histones), and (D) HR-induced NETosis in HbSS and HbAA mice. Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each data point representing a single animal. Treatment groups were compared with the vehicle group using a 2-way ANOVA, with FDR correction for multiple comparisons. Significance levels: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HbSS, red; HbAA, blue. BL, baseline; Veh, vehicle-treated.

Impact of R788 on neutrophil counts and NETosis induced by TNF-α and HR. (A) Bar graphs showing the effect of R788 on TNF-α–induced neutrophilia in HbSS and HbAA mice. (B) Effect of R788 on HR-induced neutrophilia in HbSS and HbAA mice. (C) Treatment effect of 2 g/kg of R788 for 7 days on TNF-α–induced NETosis (neutrophils [percent] expressing extracellular DNA, myeloperoxidase, and tricitrullinated histones), and (D) HR-induced NETosis in HbSS and HbAA mice. Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each data point representing a single animal. Treatment groups were compared with the vehicle group using a 2-way ANOVA, with FDR correction for multiple comparisons. Significance levels: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HbSS, red; HbAA, blue. BL, baseline; Veh, vehicle-treated.

NETosis observed (supplemental Figure 5)57 at baseline was similar in HbSS and HbAA mice (NETosis: HbSS, 4.1% ± 3.3% vs HbAA, 8.0% ± 3.7%; P = .34). After TNF-α injection, vehicle-treated HbSS mice exhibited an eightfold increase in NETosis compared with baseline (NETosis: TNF-α induced, 32.7% ± 18.4% vs baseline, 4.1% ± 3.3%; P < .0001). However, R788 treatment at 2 g/kg for 7 days, did not affect TNF-α–induced NETosis (Figure 3C) despite adequate suppression of neutrophil p-Syk (Figure 2D) and neutrophilia (Figure 3A) at this dose. Interestingly, Syk inhibition with R788 tested in a small cohort of HbSS mice (n = 3) at 3 g/kg for 14 days significantly reduced TNF-α–induced NETosis compared with vehicle (NETosis: vehicle, 32.7% ± 18.4%; R788-treated, 1.6% ± 1.6%; P = .04). These data suggest that although suppression of NETosis may require a higher threshold of Syk inhibition, this is accompanied by significant hematologic toxicity. HbAA mice displayed similar responses to TNF-α, showing increased inducible NETosis compared with baseline (NETosis: TNF-α induced, 34.6% ± 17.8% vs baseline, 12.7% ± 3.7%; P < .0001) but no significant suppression of TNF-α–induced NETosis after R788 treatment (Figure 3C).

HR exposure in HbSS mice led to a sixfold increase in NETosis compared with baseline (NETosis: HR induced, 46.2% ± 12.0% vs baseline, 4.1% ± 3.3%; P = .0007). However, in HbSS mice Syk inhibition with R788 (2 g/kg for 7 days) did not significantly attenuate HR-induced NETosis compared with vehicle (Figure 3D), despite significant suppression of neutrophil p-Syk at this dose. Consistent with previous reports,43 HR did not induce NETosis in HbAA mice, and R788 yielded no significant effects (Figure 3D).

Taken together, these data indicate that TNF-α–induced NETosis is not genotype specific, because it occurred in HbAA and HbSS mice, and is not attenuated by Syk inhibition with R788 at tolerable doses. In contrast, HR-induced NETosis is genotype specific, and does not appear to be regulated by Syk signaling.

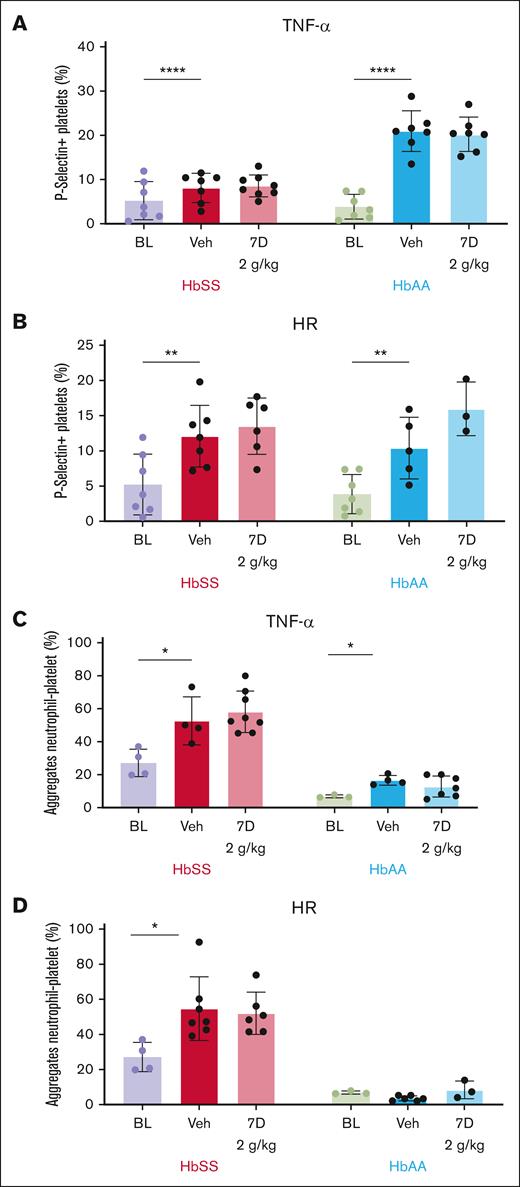

R788 at nontoxic doses does not alter TNF-α– or HR-induced platelet P-selectin expression

At baseline unstimulated condition, platelet surface P-selectin expression evaluated by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 6) was significantly higher in HbSS than HbAA mice (P-selectin–positive platelets: HbSS, 5.2% ± 4.3% vs HbAA, 3.8% ± 2.7%; P < .0001). Platelet counts were not affected by TNF-α injection or HR exposure. Platelet P-selectin expression increased significantly after TNF-α injection in vehicle-treated HbSS mice compared with baseline (P-selectin–positive platelets: TNF-α induced, 8.1% ± 3.3% vs baseline, 5.2% ± 4.3%; P < .0001) and R788 treatment had no impact compared with vehicle treatment (Figure 4A). In HbAA mice, TNF-α increased platelet P-selectin expression fivefold compared with baseline (P-selectin–positive platelets: TNF-α, 20.9% ± 4.6% vs baseline, 3.8% ± 2.7%; P < .0001) but was not affected by R788 treatment (Figure 4A). R788 at 3 g/kg for 14 days tested in a small cohort of HbSS mice (n = 3) significantly reduced TNF-α–induced platelet P-selectin expression compared with vehicle treatment (P-selectin–positive platelets: vehicle, 8.1% ± 3.3% vs 3 g/kg 14 days, 2.8% ± 1.7%; P = .01).

Effect of R788 on agonist-induced platelet surface P-selectin expression and circulating PNA. Bar graphs showing the percentage of P-selectin–positive platelets in whole blood at baseline and induced by either TNF-α (A) or HR (B) in vehicle- and R788-treated (2 g/kg dose for 7 days) HbSS and HbAA mice. Bar graphs showing the percentage of circulating PNA induced by either TNF-α (C) or by HR (D) in HbSS and HbAA mice, and the effect of R788 treatment at 2 g/kg for 7 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each data point representing a single animal. Treatment groups were compared with the vehicle group using a 2-way ANOVA, with FDR correction for multiple comparisons. Significance levels: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HbSS, red; HbAA, blue. BL, baseline; Veh, vehicle-treated.

Effect of R788 on agonist-induced platelet surface P-selectin expression and circulating PNA. Bar graphs showing the percentage of P-selectin–positive platelets in whole blood at baseline and induced by either TNF-α (A) or HR (B) in vehicle- and R788-treated (2 g/kg dose for 7 days) HbSS and HbAA mice. Bar graphs showing the percentage of circulating PNA induced by either TNF-α (C) or by HR (D) in HbSS and HbAA mice, and the effect of R788 treatment at 2 g/kg for 7 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each data point representing a single animal. Treatment groups were compared with the vehicle group using a 2-way ANOVA, with FDR correction for multiple comparisons. Significance levels: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HbSS, red; HbAA, blue. BL, baseline; Veh, vehicle-treated.

Exposure to HR led to a twofold increase in platelet P-selectin expression in HbSS mice compared with baseline (P-selectin–positive platelets: HR induced, 12.0% ± 4.3% vs baseline, 5.2% ± 4.3%; P = .0017). However, R788 had no detectable effect on HR-induced platelet P-selectin expression compared with vehicle (P-selectin–positive platelets: vehicle, 12.0% ± 4.3%; R788 2 g/kg for 7 days, 13.5% ± 4.0%; P = .56; Figure 4B). In HbAA mice, HR exposure led to a twofold increase in platelet P-selectin expression over the baseline (P-selectin–positive platelets: baseline, 3.8% ± 2.7%; HR induced, 10.3% ± 4.3%; P = .0017) and R788 at 2 g/kg for 7 days had no effect (Figure 4B).

R788 at nontoxic doses had no effect on formation of circulating PNA

In line with previous studies,66 circulating PNA (supplemental Figure 7) at baseline were almost fivefold higher in HbSS mice then HbAA mice (PNA: HbSS, 27.1% ± 8.3% vs HbAA, 6.8% ± 0.8%; P < .0001). Injection of TNF-α in HbSS mice increased circulating PNA compared with baseline (PNA: TNF-α induced, 52.6% ± 14.5% vs baseline, 29.9% ± 7.6%; P = .0022) but R788 had no discernable effect on PNA compared with vehicle (Figure 4C). HbAA mice displayed significant elevation in the percentage of circulating PNA induced by TNF-α compared with baseline levels (PNA: TNF-α induced, 16.6% ± 2.9% vs baseline, 6.8% ± 0.8%; P = .02) and this change was not affected by R788 treatment (Figure 4C).

Exposure to HR significantly increased circulating PNA in HbSS mice compared with baseline (PNA: HR induced, 54.6% ± 18.1% vs baseline, 29.9% ± 7.6%; P = .0022) and R788 had no effect on PNA (Figure 4D). In HbAA mice, HR exposure did not increase PNA formation (Figure 4D). Taken together, these findings suggest that Syk signaling likely plays a nondominant role in PNA formation induced by TNF-α or HR injury pathophysiology in HbSS mice.

Discussion

Syk is widely expressed in hematopoietic cells, including neutrophils and platelets,30,31,34,35,67,68 in which it plays a crucial role in innate immune and inflammatory responses relevant to sickle pathophysiology. This makes Syk inhibition a potentially useful therapeutic approach to mitigate SCD-related complications.30,68,69 Here, we report, to our knowledge, for the first time, the effect of a selective Syk inhibitor in Townes sickle mice specifically modeling inflammatory and HR stress pathobiology. Inhibiting Syk signaling with R788 in Townes sickle mice was associated with the following findings: (1) reduced splenomegaly, impaired erythropoiesis, and worsened anemia, likely due to the suppression of hematopoiesis; (2) attenuation of neutrophilia in response to both TNF-α and HR challenges and induction of neutropenia, likely secondary to suppression of hematopoiesis; (3) increase in total plasma bilirubin levels without directly affecting hemolysis; (4) failure to affect TNF-α– and HR-induced NETosis at nontoxic doses; and (5) failure to affect platelet P-selectin expression or the number of circulating PNA triggered by both TNF-α injection or HR challenge at nontoxic doses. Given the broad expression of Syk in hematopoietic cells and its critical role in cellular function, therapies targeting Syk signaling should be approached cautiously in hemolytic conditions associated with stress erythropoiesis, such as SCD.

Unlike humans with SCD that undergo early splenic atrophy,70 Townes sickle mice exhibit splenomegaly, with splenic extramedullary hematopoiesis compensating for severe hematopoietic stress induced by continued hemolysis and anemia.63,71 The lack of elevation in hemolysis markers, lactate dehydrogenase, and plasma Hb (except for 3 g/kg for 7 days) coupled with a dramatic reduction in spleen size, and reduced splenic and BM hematopoiesis, indicate that R788-induced worsened anemia resulted from reduced RBC production, rather than increased peripheral destruction. BM neutrophils expressed high levels of Syk and Syk signaling is involved in the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.31,72 Therefore, in the setting of hemolytic conditions such as SCD that exhibits stress erythropoiesis, inhibiting Syk signaling can profoundly worsen anemia.

Small-molecule inhibitors, by nature of target specificity, offer several advantages, including reduced toxicity compared with traditional treatments. However, as we observed in this study, disease-specific dynamics likely played a role in the toxicity of R788 in SCD. Syk is ubiquitously expressed and has a critical role in hematopoietic cell function. In a setting of stress hematopoiesis, such as in SCD, Syk inhibition was associated with undesirable and possibly off-target effects. We observed R788-induced reduction in RBC and neutrophil counts, resulting in severe anemia and neutropenia. The reduction in spleen weight and neutrophilic inflammation is particularly notable, because these are key markers of disease severity and systemic inflammation in sickle cell pathophysiology. The observed interaction further supports the hypothesis that Syk inhibition may modulate disease-associated immune dysregulation in a genotype- and, consequently, disease-dependent manner. These effects necessitate precise dosing and close monitoring for adverse reactions, especially those related to drug interactions.1,73 Patients with SCD treated with hydroxyurea show improvement in their anemia but experience dose-dependent neutropenia.6,74 Although R788 effectively inhibited basal neutrophilia and neutrophil response to thromboinflammatory and HR stress, concomitant use of a Syk inhibitor with hydroxyurea raises the possibility of life-threatening neutropenia.75 Off-target effects on platelets were minimal, as megakaryopoiesis is primarily regulated by the thrombopoietin and myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene (TPO/MPL) signaling rather than Syk signaling, and platelet function is influenced by several redundant pathways.76

When activated, neutrophils undergo NETosis,24 extruding extracellular chromatin that serves as an intravascular scaffold for assembly of coagulation complexes and promotes venous thrombosis.77,78 Indeed, patients with SCD, especially those undergoing acute VOC, exhibit dysregulated NETosis,9,12-14 and are at greater risk of developing venous thrombosis than healthy, race-matched controls.79 NETosis induced by the inflammatory stimuli was attenuated by R788 treatment in our study, consistent with previous literature,39,40,80,81 but only at doses that caused significant hematologic toxicity, suggesting limited disease-specific utility of this small-molecule inhibitor. Additionally, at a therapeutically feasible, nontoxic doses, HR-induced NETosis was unaffected, suggesting that in patients with SCD experiencing VOC in which HR pathophysiology is involved,39,40 this approach is likely to be inadequate. Although p-Syk in neutrophils was inhibited, suggesting adequate oral R788 dosing,82,83 the induction of NETosis induced by HR challenge was not adequately blunted, contrasting with results from previous studies of R788 on ischemia-reperfusion injury–associated NETosis.82,83 It is likely that methodological differences between these published studies and our study explain, in part, these unexpected results. Moreover, NETosis is among the more complex of neutrophil functions, with multiple redundancies in upstream and downstream regulatory pathways.84 Therefore, although Syk plays a vital role in NETosis,81,85 several pathways distinct to Syk are likely to be activated by varied pathophysiological stressors,40,80,81,86 and explain these discrepancies. From this vantage point, selective Syk inhibitors appear to have limited utility as inhibitors of NETosis in SCD.

Studies have shown that targeting P-selectin with crizanlizumab reduces the frequency of VOC in patients with SCD.87,88 Syk signaling plays a key role in platelet activation, and patients with SCD have higher surface P-selectin expression, which, in turn, can activate neutrophils during aggregate formation.28,44,89 Inhibiting Syk with R788 at tolerable doses had no discernable effect on reducing platelet P-selectin expression or circulating PNA after either TNF-α or HR challenge. These findings suggest that Syk may not play a critical role in regulating platelet responses to TNF-α or HR under the conditions tested, and that its inhibition may have limited impact on platelet-related pathology in the context of SCD.

The findings of our study should be interpreted within the context of its strengths and limitations. Selective inhibition of Syk signaling was attempted in a well characterized murine model of SCD both at baseline and after stressor challenges intended to mimic thromboinflammatory and HR stress pathophysiology observed in patients with SCD. By studying key biomarker end points in RBC, neutrophils, and platelets, our results provide a comprehensive picture of the impact of selective Syk inhibition on SCD pathobiology. However, there are limitations to consider. Murine studies do not fully replicate human disease and often yield results that are not reproducible in humans.71 Moreover, species differences particularly related to hematopoiesis and drug metabolism48 should be considered when extrapolating these results of our study to humans. We did not directly assess the molecular mechanisms responsible for worsening anemia in HbSS mice or identified the direct effect of treatment on neutrophil precursor populations in the BM, which was beyond the scope of our study. Instead, we assessed total CFUs, as a functional readout of myeloid progenitor activity. Although this assay provides valuable insight into hematopoietic output, it does not distinguish between specific stages of neutrophil differentiation or maturation. Therefore, we cannot definitively conclude whether the observed reduction in peripheral neutrophil counts after R788 treatment reflects a decrease in precursor numbers, a maturation defect, or altered trafficking. Future studies incorporating flow cytometric or cytologic analysis of BM precursors may more precisely define the mechanism by which R788 influences neutrophil development. Moreover, off-target effects of R788 led to severe hematologic toxicity and hindered our ability to assess the long-term effects of Syk inhibition in Townes sickle mice. However, our results show that short-term R788 exposure substantially worsens anemia, suggesting broader effects on hematopoiesis in hemolytic disorders that are accompanied by stress erythropoiesis.

In conclusion, our studies highlight the impact of selective targeting of Syk with the small-molecule inhibitor R788 in a murine model of SCD, leading to off-target inhibition of hematopoiesis, worsening anemia, and inducing neutropenia. These findings illustrate that R788 toxicity is intricately related to disease-specific dynamics as we noted in SCD mice. This work also underscores the utility of preclinical studies in Townes sickle cell mice, which provide a comprehensive biological system for studying small-molecule inhibitors and their disease-specific effects. Further research is needed to clarify the potential of selective Syk inhibitors as immunomodulatory therapy for the treatment of SCD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rigel Pharmaceuticals for providing R788 and vehicle-containing chow for the experiments; Richard Childs, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI); Jeffrey R. Strich, Laboratory of Critical Illness Pathogenesis and Therapeutics, NHLBI; Maria Lopes Ocasio, NHLBI Flow Cytometry Core; and Christian Combs, NHLBI Light Microscopy Core for their assistance with this study.

This research was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health and National Institute of Health Clinical Center.

The contributions of the NIH authors are considered works of the US Government. The findings and conclusions presented in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Authorship

Contribution: B.P.G. designed the research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; S.K. performed experiments and analyzed data; P.D. provided guidance with the flow cytometry experiments; N.S. performed histopathological evaluations; D.-Y.L. performed R406 measurements; M.Q. supervised and performed histopathological evaluations; Z.Q. analyzed data, provided critical guidance on experimental procedures, and reviewed the manuscript; and A.S.S. designed the research, provided critical guidance on experimental procedures and overall supervision, acquired funding, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Arun S. Shet, Sickle Cell Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 10 Center Dr, Building 10, Room 6S241, MSC 1589, Bethesda, MD 20892-1589; email: arun.shet@nih.gov.

References

Author notes

Z.Q. and A.S.S. contributed equally to this study.

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Arun S. Shet (arun.shet@nih.gov).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Impact of R788 on neutrophil counts and NETosis induced by TNF-α and HR. (A) Bar graphs showing the effect of R788 on TNF-α–induced neutrophilia in HbSS and HbAA mice. (B) Effect of R788 on HR-induced neutrophilia in HbSS and HbAA mice. (C) Treatment effect of 2 g/kg of R788 for 7 days on TNF-α–induced NETosis (neutrophils [percent] expressing extracellular DNA, myeloperoxidase, and tricitrullinated histones), and (D) HR-induced NETosis in HbSS and HbAA mice. Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each data point representing a single animal. Treatment groups were compared with the vehicle group using a 2-way ANOVA, with FDR correction for multiple comparisons. Significance levels: ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. HbSS, red; HbAA, blue. BL, baseline; Veh, vehicle-treated.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodvth/3/1/10.1016_j.bvth.2025.100118/1/m_bvth_vth-2025-000395-gr3.jpeg?Expires=1769085699&Signature=y6quS6DhPb122FHMbwRaDJQNnV26U9sHE~tKwiDU571opXy~Q7L7MZsCspUVguSOpYpvmpqs1juYkTak7e7lwQbpM6l3fG27QZC~e6hwf-IL8WU~WOARul1bG7XIlcbyYJLpzET39FaqTlFZe00K8Hzam9NHfuZurcmMp4aqbhgqWEu56noziDpf1Wh5v4LGMZp6UnKOuo7Tjxmnu6q0WBTWYHPtJRviqUAZpaGuseQemjKIm32M-4sEd2qfinpK69oLGTb4cfyxUsy2zOAoaH1O2Mvpj7a6D-OjI09PcikzrDnMfx74fvl6yaJ6i2XLZ7VrVjU8qaO-xqYBoRwydg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)