Key Points

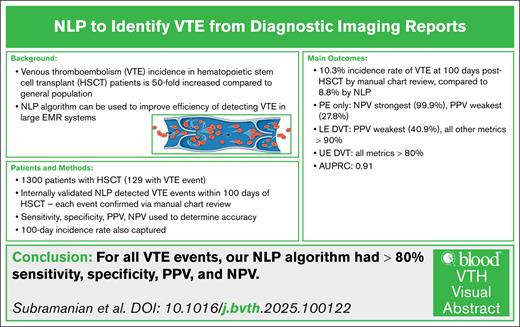

The 100-day VTE incidence rate by manual chart review and our institutional NLP was 10.3% and 8.8%, respectively.

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of the NLP were ≥85% when considering all VTE events.

Visual Abstract

The annual incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) may be 50-fold increased after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). Such incidence data, as well as data that establish clinical variables resulting in this enhanced risk, have generally required manual chart review. This cumbersome process can be improved by natural language processing (NLP) algorithms designed to detect VTE in electronic medical record systems. We describe the development of an institutional NLP algorithm for VTE detection, and our evaluation of its performance in detecting VTE in patients who recently underwent HSCT. We retrospectively reviewed adult patients between 2016 and 2020. NLP assessed patient records for acute VTE within 100 days of HSCT, and manual chart review was performed for comparison. NLP sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated. A total of 1300 electronic health records were analyzed. The 100-day VTE incidence rate as determined via manual chart review and NLP was 10.3% and 8.8%, respectively. NLP’s specificity, sensitivity, PPV, and NPV were >0.85. Of the 19 events not identified by NLP, all were found in radiology or vascular laboratory reports overlooked by NLP. These results demonstrate excellent performance of NLP for identifying VTE in HSCT patients. Future refinement of NLP, and its combination with other detection methods should provide better detection of VTE in this and other at-risk cohorts.

Introduction

The annual incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is ∼1 to 2 events per 1000,1 with a roughly 50-fold increase after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).2 Elucidating the risk factors, treatment effects, and clinical outcomes will have a significant impact on morbidity and mortality associated with HSCT-associated VTE.3 In retrospective studies, conventional methodology for the detection and adjudication of VTE is manual chart review, which is not always feasible for large databases and electronic medical record (EMR) systems because of the substantial time needed.4 The International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) has attempted to codify VTE more easily for simpler documentation, but it is dependent on subjective clinician review and has been shown to have a higher false positive and false negative rate than chart review.5 One retrospective study found that although the sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) of ICD-10 were extremely high (indicating a low false negative rate), the specificity and positive predictive value (PPV) were lower (indicating a relatively high false positive rate), and the researchers’ recommendation was to use ICD-10 codes to rule out VTE events but not to identify VTE events without confirmatory manual chart review.6

Natural language processing (NLP) algorithms have been designed to improve the detection of VTE in EMR systems.7 One study of 935 positive VTE events showed that the use of NLP had a sensitivity and specificity >90% and a PPV of 73%, indicating a decreased false positive and false negative rate.8 Another retrospective study showed sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of >90% for detecting VTE using NLP.9 Another study showed that NLP had a PPV of 85% and a sensitivity of 95%,10 whereas another showed an improved sensitivity and specificity when detecting pulmonary embolism (PE; 90% and 99%, respectively) vs extremity VTE (85% and 94%, respectively).11 A recent meta-analysis showed that the pooled sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of different NLP algorithms in the literature were all >90%, although only a small percentage of these studies had external validation of their models.12

This study aims to evaluate our institution’s NLP algorithm and its performance in detecting VTE in patients who recently underwent HSCT.

Methods

Patient population selection

This was a single center, retrospective study that identified adult (aged ≥18 years) patients who underwent first allogeneic HSCT between April 2016 and December 2020 at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC). Patients were identified through a registry database prospectively collected at the Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapy department. Dates of inclusion were selected according to the inception of the most current EMR platform used at the MDACC at the time of the study.

Outcome definitions

Acute VTE events were identified within the 100 days following the HSCT date via either the ICD-10 codes or NLP reports from diagnostic imaging (DI) studies and were confirmed by physician chart review as the standard. VTE events were confirmed on physician manual chart review based on confirmed imaging-based diagnosis. The 100-day mark was chosen to ensure that the detection tests were conducted at our institution. VTE that met the standard criteria for acute VTE by the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis guidelines were included as events in the analysis.13 Splanchnic and central nervous system locations of VTE were not included in this study.

All EMRs were searched for relevant VTE-specific ICD-10-Clinical Modification codes from EMR diagnoses and verified through manual EMR review (supplemental Table 1). In addition, we applied an automated NLP algorithm, which was developed at MDACC, to all venous ultrasound and contrast-enhanced radiology reports performed within −7 and +100 days from the HSCT date. Those events were also verified by subject matter experts (SME) through manual EMR review.

NLP development and clinical SME validation

We developed a text-parsing program called VTE NLP annotator using IBM Watson Explorer Content Analytics Studio. It looks for VTE events documented in the impression section of a DI report. It uses a dictionary of VTE events (eg, deep vein thrombosis [DVT], tumor thrombosis, PE, and venous thrombi), dictionary of indication of VTE (eg, Yes, No, Possible, and Probable), dictionary of progression (Yes and No), dictionary of human anatomic body sites (femoral vein, portal vein, arm, leg, etc) and laterality, and different patterns of radiologists’ descriptions of VTE events.

The VTE NLP annotator parses out individual VTE events associated with its indication, anatomic site, and laterality. A business rule is then created to report on overall DVT/PE status from the whole DI report. For example, a venous thrombi identified in the femoral vein is reported as DVT because femoral vein is a deep vein even though DVT is not used in the original report. The annotator is exported as a Java archive file from IBM Watson Explorer Content Analytics Studio and deployed into IBM Watson Explorer server to run on all the diagnostic reports within the chosen time frame, with the ability to analyze tens of thousands of DI reports.

Between April 2017 and July 2017, our institution performed a validation of the VTE NLP technique in confirming VTE events. This validation was manually performed by SMEs who were blinded to the results of the NLP technique. SMEs individually reviewed random samples among all eligible DI reports performed by NLP. The physician experts’ identifications were considered the gold standard for determining the accuracy of classification of the VTE by the NLP technique. Any discrepancies were reevaluated by the entire group of SMEs. A total of 1756 randomly selected reports were included in the validation, with a simple κ coefficient of 0.89 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.86-0.91), which indicated an almost perfect interrater reliability for the adjudication of VTE between SMEs and NLP.14 We chose to use our NLP tool because at the time, other machine learning options such as ChatGPT had not been introduced.

Statistical analysis

Assessments of predicting a VTE event for the NLP algorithm were determined using sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy (ie, proportion of true positive and true negative) statistics along with corresponding 95% CIs. Time-to-VTE events were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Patients who did not experience an event were censored at their last follow-up visit. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

This study was approved by the institutional review board at MDACC.

Results

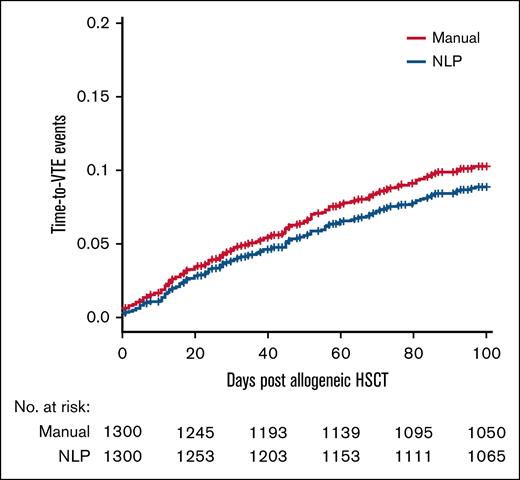

We analyzed 1300 patient charts retrospectively for a VTE event within 100 days of HSCT. In our patient cohort, 129 patients had a detected VTE event. Baseline characteristics of the patient population are listed in Table 1. Of the 129 VTE events that were detected, 113 (87.6%) were catheter-related upper extremity DVTs, 10 (7.8%) were lower extremity DVTs, and 6 (4.7%) were PEs. Figure 1 shows the time-to-VTE events based on both manual chart review and the NLP algorithm for the first 100 days after HSCT, stratified by 20-day intervals. The total 100-day incidence rate of VTE as determined by manual chart review and the NLP algorithm was 10.3% and 8.8%, respectively, with a difference of 1.5% between the 2 methods (Figure 1). When looking at the NLP algorithm alone for all VTEs, every metric was found to be >80% accurate; the sensitivity was the weakest at 85.3%, whereas the specificity was particularly strong at 98.9% (Table 2). The area under the precision-recall curve of the data set was 0.91.

Baseline characteristics of the patient population

| Variable . | Frequency (N = 1300) . |

|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 773 (59.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 964 (74.2) |

| Black | 99 (7.6) |

| Asian | 71 (5.5) |

| Other | 166 (12.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 216 (16.6) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 1031 (79.3) |

| Unknown | 53 (4.1) |

| Disease category, n (%) | |

| ALL | 164 (12.6) |

| AML/MDS | 765 (58.8) |

| Aplastic anemia | 21 (1.6) |

| CLL | 52 (4.0) |

| CML/MPD | 158 (12.2) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 19 (1.5) |

| Other lymphoma | 91 (7.0) |

| Multiple myeloma | 25 (1.9) |

| Sarcoma | 2 (0.2) |

| Other hematologic malignancies | 3 (0.2) |

| Donor type, n (%) | |

| Matched related | 452 (34.8) |

| Matched unrelated | 674 (51.8) |

| Mismatched related | 174 (13.4) |

| Mean age ± SD, y | 50.8 ± 15.4 |

| Mean BMI ± SD, kg/m2 | 28.1 ± 6.3 |

| Mean Karnofsky score ± SD | 86.5 ± 9.4 |

| Variable . | Frequency (N = 1300) . |

|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 773 (59.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 964 (74.2) |

| Black | 99 (7.6) |

| Asian | 71 (5.5) |

| Other | 166 (12.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 216 (16.6) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 1031 (79.3) |

| Unknown | 53 (4.1) |

| Disease category, n (%) | |

| ALL | 164 (12.6) |

| AML/MDS | 765 (58.8) |

| Aplastic anemia | 21 (1.6) |

| CLL | 52 (4.0) |

| CML/MPD | 158 (12.2) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 19 (1.5) |

| Other lymphoma | 91 (7.0) |

| Multiple myeloma | 25 (1.9) |

| Sarcoma | 2 (0.2) |

| Other hematologic malignancies | 3 (0.2) |

| Donor type, n (%) | |

| Matched related | 452 (34.8) |

| Matched unrelated | 674 (51.8) |

| Mismatched related | 174 (13.4) |

| Mean age ± SD, y | 50.8 ± 15.4 |

| Mean BMI ± SD, kg/m2 | 28.1 ± 6.3 |

| Mean Karnofsky score ± SD | 86.5 ± 9.4 |

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BMI, body mass index; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MPD, myeloproliferative disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Time-to-VTE event as determined by manual chart review (in red) and NLP algorithm (in blue).

Time-to-VTE event as determined by manual chart review (in red) and NLP algorithm (in blue).

Evaluation metrics

| VTE type . | Measure . | VTE . | No VTE . | Sensitivity (95% CI), % . | Specificity (95% CI), % . | Accuracy (95% CI), % . | PPV (95% CI), % . | NPV (95% CI), % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any | NLP | 85.3 (79.2-91.4) | 98.9 (98.3-99.5) | 97.5 (96.7-98.4) | 89.4 (84.0-94.9) | 98.4 (97.7-99.1) | ||

| VTE | 110 | 13 | ||||||

| No VTE | 19 | 1158 | ||||||

| PE | NLP | 83.3 (53.5-100) | 98.9 (98.3-99.5) | 98.8 (98.2-99.4) | 27.8 (7.1-48.5) | 99.9 (97.7-100) | ||

| VTE | 5 | 13 | ||||||

| No VTE | 1 | 1158 | ||||||

| Lower extremity DVT | NLP | 90.0 (71.4-100) | 98.9 (98.3-99.5) | 98.8 (98.2-99.4) | 40.9 (20.4-61.5) | 99.9 (97.7-100) | ||

| VTE | 9 | 13 | ||||||

| No VTE | 1 | 1158 | ||||||

| Catheter-related DVT | NLP | 85.0 (78.4-91.6) | 98.9 (98.3-99.5) | 97.7 (96.8-98.5) | 88.1 (82.0-94.2) | 98.6 (97.9-99.2) | ||

| VTE | 96 | 13 | ||||||

| No VTE | 17 | 1158 | ||||||

| Manual chart review | Prediction measure | |||||||

| VTE type . | Measure . | VTE . | No VTE . | Sensitivity (95% CI), % . | Specificity (95% CI), % . | Accuracy (95% CI), % . | PPV (95% CI), % . | NPV (95% CI), % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any | NLP | 85.3 (79.2-91.4) | 98.9 (98.3-99.5) | 97.5 (96.7-98.4) | 89.4 (84.0-94.9) | 98.4 (97.7-99.1) | ||

| VTE | 110 | 13 | ||||||

| No VTE | 19 | 1158 | ||||||

| PE | NLP | 83.3 (53.5-100) | 98.9 (98.3-99.5) | 98.8 (98.2-99.4) | 27.8 (7.1-48.5) | 99.9 (97.7-100) | ||

| VTE | 5 | 13 | ||||||

| No VTE | 1 | 1158 | ||||||

| Lower extremity DVT | NLP | 90.0 (71.4-100) | 98.9 (98.3-99.5) | 98.8 (98.2-99.4) | 40.9 (20.4-61.5) | 99.9 (97.7-100) | ||

| VTE | 9 | 13 | ||||||

| No VTE | 1 | 1158 | ||||||

| Catheter-related DVT | NLP | 85.0 (78.4-91.6) | 98.9 (98.3-99.5) | 97.7 (96.8-98.5) | 88.1 (82.0-94.2) | 98.6 (97.9-99.2) | ||

| VTE | 96 | 13 | ||||||

| No VTE | 17 | 1158 | ||||||

| Manual chart review | Prediction measure | |||||||

We then stratified the performance of the NLP algorithm by the type of VTE. When only PEs were considered, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and NPV were at least 80%, with the NPV being particularly strong (99.9%); however, the PPV was poor (27.8%). When only lower extremity DVTs were considered, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and NPV were at least 90%, with the NPV again being particularly strong (99.9%); however, the PPV was once again poor (40.9%). When only catheter-related upper extremity DVTs were considered, every metric was found to be >80%; the sensitivity was the weakest at 85.0%, whereas the specificity was particularly strong at 98.9% (Table 2).

There were 19 acute VTE cases missed by the NLP algorithm, as described in Table 3. The manual medical record review of those cases showed that all had a radiologic report conducted at MDACC, which confirmed the acute VTE diagnosis. It is important to highlight that 4 missed cases were diagnosed from days −7 to −1 from the transplant date during the hospitalization for transplant preparation, indicating that although they were at higher risk of developing VTE post-HSCT, they did not actually have a missed post-HSCT VTE event. Seventeen of the undetected cases (89.5%) corresponded to DVT of the upper extremities, 1 case (5.3%) corresponded to DVT of the lower extremities, and 1 case (5.3%) corresponded to PE.

Qualitative descriptions of VTE events missed by NLP

| Number . | Location . | Vein . | Imaging modality used . | Reason for NLP noncapture . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LUE | Subclavian | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 2 | PE | Right main pulmonary | PET/CT | NLP read as negative |

| 3 | LUE | Subclavian, axillary | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 4 | RUE | Axillary | RUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 5 | RUE | Subclavian | RUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 6 | LUE | Axillary (around the PICC) | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 7 | LUE | Subclavian | LUE Doppler US | NLP read as negative |

| 8 | RUE | Innominate | RUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 9 | LLE | Femoral, popliteal | BLE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 10 | LUE | Subclavian | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 11 | RUE | Subclavian, axillary | BUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 12 | LUE | Subclavian | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 13 | LUE | Axillary | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 14 | LUE | Subclavian, axillary | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 15 | RUE | Subclavian, IJ | RUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 16 | RUE | Subclavian, axillary, brachial | RUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 17 | LUE | Subclavian, axillary | BUE Doppler US | NLP read as negative |

| 18 | LUE | IJ | BUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 19 | RUE | IJ | RUE Duplex US | NLP missed the study |

| Number . | Location . | Vein . | Imaging modality used . | Reason for NLP noncapture . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LUE | Subclavian | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 2 | PE | Right main pulmonary | PET/CT | NLP read as negative |

| 3 | LUE | Subclavian, axillary | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 4 | RUE | Axillary | RUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 5 | RUE | Subclavian | RUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 6 | LUE | Axillary (around the PICC) | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 7 | LUE | Subclavian | LUE Doppler US | NLP read as negative |

| 8 | RUE | Innominate | RUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 9 | LLE | Femoral, popliteal | BLE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 10 | LUE | Subclavian | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 11 | RUE | Subclavian, axillary | BUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 12 | LUE | Subclavian | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 13 | LUE | Axillary | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 14 | LUE | Subclavian, axillary | LUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 15 | RUE | Subclavian, IJ | RUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 16 | RUE | Subclavian, axillary, brachial | RUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 17 | LUE | Subclavian, axillary | BUE Doppler US | NLP read as negative |

| 18 | LUE | IJ | BUE Doppler US | NLP missed the study |

| 19 | RUE | IJ | RUE Duplex US | NLP missed the study |

BLE, bilateral lower extremities; BUE, bilateral upper extremities; IJ, internal jugular; LLE, left lower extremity; LUE, left upper extremity; PET/CT, positron emission tomography/computed tomography; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; RUE, right upper extremity; US, ultrasound.

There were 13 cases where the NLP judged the presence of a VTE that was not corroborated by manual chart review, as described in Table 4. Of these 13 cases, 4 (30.8%) were reads of probable VTEs that were not actually identified, 3 (23.1%) were superficial VTEs that were captured, 5 (38.5%) were chronic VTEs (not acute events), and 1 (7.7%) was an arterial thrombotic event.

Qualitative descriptions of non-VTE events captured by NLP

| Number . | Imaging modality read . | Reason for NLP capture . | Detailed reason for NLP capture . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CT abdomen/pelvis | Probable VTE | Probable PE noted and found to be negative for PE on dedicated imaging |

| 2 | LUE Doppler US | Superficial VTE | NLP captured superficial venous thrombosis |

| 3 | LUE Doppler US | Chronic VTE | NLP captured chronic DVT |

| 4 | LLE arterial Doppler US | Arterial thrombosis | NLP captured arterial thrombosis of the left femoral artery pseudoaneurysm |

| 5 | CT chest PE | Chronic VTE | PE captured on NLP was found to be chronic after review of prior PET/CT |

| 6 | RLE Doppler US | Chronic VTE | NLP captured chronic DVT of the femoral vein |

| 7 | CT chest PE | Chronic VTE | NLP captured chronic PE from prior to HSCT |

| 8 | CT chest | Probable VTE | NLP captured mosaic attenuation of the lung with possible chronic PE |

| 9 | RUE Doppler US | Superficial VTE | NLP captured superficial thrombosis in the RUE |

| 10 | RUE Doppler US | Probable VTE | Small avascular hypoechoic structure noted on imaging |

| 11 | LUE Doppler US | Superficial VTE | Occlusive superficial VTE of the cephalic vein |

| 12 | CT abdomen/pelvis | Probable VTE | Probable PE initially and found to have low probability on V/Q |

| 13 | RLE Doppler US | Chronic VTE | NLP detected chronic thrombus of the popliteal vein |

| Number . | Imaging modality read . | Reason for NLP capture . | Detailed reason for NLP capture . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CT abdomen/pelvis | Probable VTE | Probable PE noted and found to be negative for PE on dedicated imaging |

| 2 | LUE Doppler US | Superficial VTE | NLP captured superficial venous thrombosis |

| 3 | LUE Doppler US | Chronic VTE | NLP captured chronic DVT |

| 4 | LLE arterial Doppler US | Arterial thrombosis | NLP captured arterial thrombosis of the left femoral artery pseudoaneurysm |

| 5 | CT chest PE | Chronic VTE | PE captured on NLP was found to be chronic after review of prior PET/CT |

| 6 | RLE Doppler US | Chronic VTE | NLP captured chronic DVT of the femoral vein |

| 7 | CT chest PE | Chronic VTE | NLP captured chronic PE from prior to HSCT |

| 8 | CT chest | Probable VTE | NLP captured mosaic attenuation of the lung with possible chronic PE |

| 9 | RUE Doppler US | Superficial VTE | NLP captured superficial thrombosis in the RUE |

| 10 | RUE Doppler US | Probable VTE | Small avascular hypoechoic structure noted on imaging |

| 11 | LUE Doppler US | Superficial VTE | Occlusive superficial VTE of the cephalic vein |

| 12 | CT abdomen/pelvis | Probable VTE | Probable PE initially and found to have low probability on V/Q |

| 13 | RLE Doppler US | Chronic VTE | NLP detected chronic thrombus of the popliteal vein |

CT, computed tomography; LLE, left lower extremity; LUE, left upper extremity; PET/CT, positron emission tomography/computed tomography; RLE, right lower extremity; RUE, right upper extremity; US, ultrasound; V/Q, ventilation/perfusion.

Discussion

When looking specifically at post–allogeneic HSCT patients, other studies have noted a similar incidence rate of VTE. One study demonstrated an 8.0% incidence of VTE in the year after allogeneic HSCT,15 which is similar to the incidence rate noted in our cohort. Another study had a cumulative VTE incidence of 11.8% at 14 years posttransplant, with a median time-to-VTE event of 211 days post-HSCT; however, there was no measure of incidence specifically at 100 days or at 1-year post-HSCT.16

Our study showed that the NLP algorithm had a consistently strong performance in identifying VTE events across all metrics when looking at the overall cohort of VTE events, with sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV all >80%. Given that most captured VTE events were catheter-related upper extremity DVTs, the strong detection accuracy of the algorithm across all metrics was maintained when looking specifically at this subgroup. For other subgroups, the algorithm maintained strong detection accuracy when evaluating sensitivity, specificity, and NPV; in fact, those metrics were strongest in the lower extremity DVT subgroup when compared with the overall cohort and both other subgroups. However, the PPV for both PE and lower extremity DVT subgroups was <50% and significantly lower than the overall cohort and catheter-related upper extremity DVT subgroups, indicating a need for refinement in the algorithm to detect true events as opposed to those that were probable. The area under the precision-recall curve of our data set (0.91), which is higher than either the sensitivity (0.85) and PPV (0.89), shows that even with the imbalance of VTE present in our data set, our algorithm has a high detection rate of VTE.

The 100-day VTE incidence in our patient cohort was 10.3% as determined by manual chart review and 8.8% as determined by the NLP algorithm. Interestingly, when stratified by the 20-day windows, the difference between the algorithm and manual chart review was <1% after the first 20 days but increased consistently after each 20-day window. This indicates that our NLP has a consistent ability to detect VTE events during the observation period. In total, our rule-based NLP annotator ran quickly and had a performance scalable to large volumes of documents with an almost perfect κ correlation coefficient (meaning a comparable identification ability with a SME).

Our NLP allowed for the efficient identification of VTE cases, which can be useful in several different settings. Given the much higher likelihood of VTE development in patients post-HSCT than in the general population,2 the utilization of such algorithms is crucial, particularly in larger academic centers with many post-HSCT patients, to more easily identify VTE cases in an efficient manner. Our NLP showed that it could process documents efficiently, with its performance scalable to a larger quantity of inputted documents, allowing for more controlled computing costs. Large-scale operations such as anticoagulation stewardship operations and automated VTE monitoring dashboards in hospital systems could be assisted by such algorithms to allow for sifting more efficiently through large quantities of data to detect cases requiring intervention. However, to allow for this to happen, there would need to be a few changes to the overall setup structure, including laying out specific criteria to distinguish between acute and chronic VTEs, defining the categories of splanchnic vein thrombosis and tumor thrombus for the SMEs reviewing each case, and developing education for radiology providers to highlight some of the common issues arising from dictation that will optimize NLP. The NLP annotator also had the advantage of being easy to either confirm true positives or debug potential errors that arose because of its ability to compare the data to predefined rules.

The increasing use of large language model (LLM) systems over the last few years has led to discussion about their role in VTE detection when compared to a more rules-based approach such as our NLP algorithm. Although LLMs have shown great efficacy in more nuanced tasks that require more diverse training data sets, such as with personalized medicine or drug delivery, it often does so with a trade-off of slower run time and worse accessibility.17 The ways in which it can assist with VTE detection involve the integration of predetermined genetic and disease-specific risk factors into a decision-making paradigm that can identify at-risk patients for early prophylaxis.17 The scope of LLM, however, is oftentimes exceedingly large for simply increasing detection from radiology reports in a more time-efficient manner when compared with NLP algorithms such as the one developed in this study.

Given the current lack of a nationwide VTE surveillance network, determining the exact incidence, especially distinguishing between acute vs chronic VTE at outside hospitals and institutions, has been a significant challenge. Although the initial rollout of NLP algorithms can be limited to its developing institution due to radiology reading patterns specific to the institution, the validation of these algorithms can allow for improved tracking of VTE incidence across multiple populations and cancer therapies. Once these algorithms have been tested for validity, they could theoretically be implemented as a plug-in feature into Epic and other large EMR systems; however, for these plug-ins to have more generalizability, the utilizing hospital or institution would need to understand and use the reading patterns of the institution that developed the algorithm.

Our study has limitations. At the current version of our NLP, we were unable to include radiology reports generated outside of our institution or those conducted by vascular physicians instead of the radiology department. Although conducting all follow-up appointments within the first 100 days at our institution limits the possibility of losing data from external reports, we anticipate that it will be necessary to modify the NLP to include external radiology data and reports from other pertinent diagnostic disciplines. There is also no standardized tool for NLP assessment that compares the runtime performance and scalability of other published systems; therefore, we could not comment on its diagnostic potential compared to a gold standard approach. Many different solutions could be used for increased ability to detect VTE retrospectively, to ensure that there is not, at present, one standard for accurate comparison. Another limitation of this study was the anatomic distribution of VTE events; most of the captured VTE events in our study were catheter-related upper extremity DVTs, with only 16 total events being lower extremity DVTs or PEs. This was a likely contributor to the lower PPV for each of these categories of VTE, as there was a limited sample size for the NLP to use.

Conclusions

The NLP algorithm developed by our institution had excellent performance in the detection of VTE events in patients with recent HSCT. This demonstrates the utility of our algorithm to perform these retrospective analyses rapidly, which will allow for its use in large-volume settings to identify and analyze at-risk patients more easily. With refinement, particularly the extension of the NLP logic to detect VTE events in radiology and other diagnostic reports performed elsewhere, this algorithm could be used to quickly screen for VTE events from radiology reports and facilitate large-scale retrospective studies, for the monitoring of VTE in clinical settings, and to evaluate the impact of thromboprophylaxis measures in hospitals and outpatient settings.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported, in part, by the Cancer Center Support Grant (National Cancer Institute grant P30 CA016672 [D.R.M.]).

Authorship

Contribution: N.S., H.G.P., D.N., A.F., M.H.K., and C.M.R.H. completed the chart review and data collection; N.S. and C.M.R.H. wrote the manuscript; D.R.M. provided the biostatistical analysis; L.C., J.L., and S.J. developed the natural language processing algorithm and wrote the associated section; and P.K., E.S., C.C.W., R.A.S., K.M.T., and M.H.K. helped edit the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.M.R.H. reports research funding from Anthos Therapeutics. R.A.S. reports research funding from Boston Scientific; and was a consultant at Inari Medical, Boston Scientific, Varian Medical Systems, Medtronic, TriSalus Life Sciences, and Replimune. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Cristhiam Rojas Hernandez, Thrombosis and Benign Hematology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Suite 1464, Houston, TX 77030; email: cmrojas@mdanderson.org.

References

Author notes

Original data are available from the corresponding author, Cristhiam M. Rojas Hernandez (cmrojas@mdanderson.org).