Key Points

HPX gene transfer using a viral vector can increase HPX expression in an animal model of sickle cell disease, without causing toxicity.

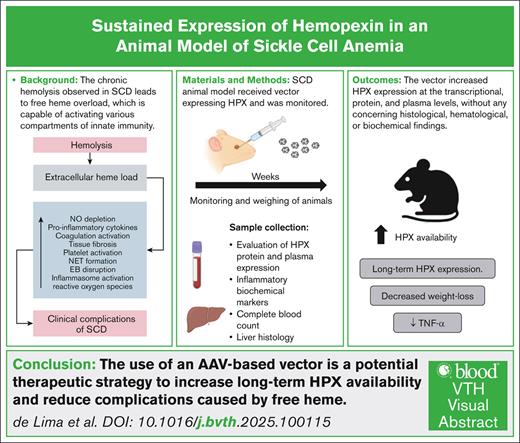

Visual Abstract

Sickle cell disease is a condition characterized by vaso-occlusive episodes and sustained hemolysis, leading to a chronic inflammatory state. Several studies have shown that the release of heme to the extracellular space due to hemolysis contributes to the inflammatory cascade observed in these patients. Hemopexin (HPX), the molecule responsible for removing excess heme from the circulation, is depleted in these patients. We have previously demonstrated that the IV infusion of an adeno-associated virus–based gene transfer vector was capable of inducing the transgenic expression of HPX in a dose-dependent manner in C57Bl6 mice. Here, we explored the effect of this vector in a mouse model of sickle cell anemia. Townes mice were transduced with 2 × 1013 vector genomes per kilogram and followed up for up to 48 weeks. HPX expression was confirmed in liver samples by both western blot and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (HPX), but gene transfer did not restore circulating levels of HPX in Townes mice, as shown in models without hemolysis. Indirect surrogate markers of a beneficial effect of delivering HPX were observed, including increased expression of heme-oxygenase 1 upon heme overload, greater weight gain on the long-term follow-up, and a significant decrease in tumor necrosis factor α levels. No signs of liver or hematological toxicity were observed. Our results demonstrate the potential and challenges of therapeutic strategies based on the long-term delivery of HPX in an animal model of sickle cell anemia.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common hemoglobinopathy in the world, and chronic intravascular hemolysis is recognized as one of the basic mechanisms driving the pathogenesis of SCD.1 Intravascular hemolysis results in the release of free heme to the extravascular space, which triggers the generation of reactive oxygen species and activates various compartments of innate immunity, conferring an important role on heme in the pathogenesis of SCD.2

Hemopexin (HPX) is a circulating protein with a high affinity for heme, responsible for removing free heme from the extravascular space, preventing its toxic effects.3 However, it has long been shown that HPX levels are depleted in conditions of chronic hemolysis, such as SCD.4 The administration of purified HPX in animal models of SCD has been shown to attenuate the proinflammatory effects of heme5,6; however, this strategy is limited by the transient effects and the need for periodic infusion of the protein.5,7

Gene therapy is gaining ground as a strategy to obtain the sustained expression of circulating proteins using viral vectors, as illustrated with hemophilia, in which several vectors have been licensed in the last years.8-10 These vectors carry the gene encoding the target protein, penetrating the cell nucleus and allowing the protein to be expressed constantly and at therapeutic levels.11

We recently demonstrated that a vector based on adeno-associated virus serotype 8 (AAV8), which carries the complementary DNA (cDNA) of the HPX gene, was able to promote sustained and dose-dependent expression of the protein in C57BL/6J mice, and was not associated with signs of systemic and hepatic toxicity.12 Our aim here was to explore the safety and efficacy of our vector in an animal model of SCD.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Heme (CAS: 16009-13-5, Frontier Scientific) was diluted in 1 M NaOH, adjusted to pH 7.4 with 3 M HCl, filtered through a 0.22-um filter, and immediately used. HPX plasma levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using commercial kit from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom), specific for the human (catalog no. ab108860) or murine (catalog no. ab157716) form of the protein. Specific antibodies for human HPX (hHPX; Abcam, catalog no. ab133523) and murine heme oxygenase 1 (mHO-1; Abcam, catalog no. ab211799) were used for the western blot experiments. The primers used have been previously described.12

Animal models

All experiments with mice were approved by the ethics committee on the use of animals at Unicamp (Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais) and obtained from the Centro Vivarium at Unicamp (Centro Multidisciplinar para Investigação Biológica na Área da Ciência em Animais de Laboratório, Campinas, Brazil). The animals used in the model of sickle cell anemia were male Townes mice, 7 to 8 weeks old, generated by introducing the human α and βS globin genes into mice with deletions of both the murine α and β genes, leading to the production of animals that exclusively express human hemoglobin S.13 The expression of human a globin mimics the polymerization observed in human with sickle cell anemia. We also used 8-week-old male C57BL/6J mice. The animals were kept in microisolators at a temperature of 20°C to 22°C, with a light/dark cycle of 12 hours, and were fed commercial chow and autoclaved water. For the heme infusion experiment, C57BL/6J mice received 70 μM/kg of heme or vehicle and were euthanized after 1 hour for sample collection.

Gene construct and vectors

The recombinant AAV8–hHPX vector, previously described,12 was used to express hHPX in Townes and C57BL/6J mice. To optimize expression, we used the same vector construct replacing the hHPX cDNA with the murine HPX (mHPX) cDNA (vector rAAV8-mHPX). As a control, we used the same construct, but without the hHPX or mHPX genes. All the vectors were produced by Virovek (Hayward, CA).

Gene transfer regimens and sample collection

The vector was diluted in saline and injected via the retro-orbital route, with the animals first anesthetized with isoflurane. The doses used were 2 × 1013 and 4 × 1014 vector genomes (vg)/kg for the rAAV-hHPX vector, and 1 × 1013 and 1 × 1014 vg/kg for the rAAV8-mHPX vector. To monitor the transgene expression, HPX blood was collected before vector infusion (baseline) and 2 and 4 weeks after infusion, via the retro-orbital route, in tubes containing 10% EDTA. For the terminal collection, blood was taken directly from the inferior vena cava in tubes containing 10% EDTA or 3.8% sodium citrate or in tubes without anticoagulant to obtain serum. To obtain plasma or serum, the tubes were centrifuged at 2500g or 1000g, respectively, for 15 minutes, aliquoted, and stored at −20°C for later analysis. Fresh liver samples were also collected for real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and western blot. For RT-PCR experiments, samples were stored in an RNA stabilizer buffer. For western blot, samples were stored in 1.5-mL tubes and immediately placed on dry ice. Samples for both RT-PCR and western blot analyses were processed with a TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Germany).

Confirmation of transgenic HPX expression

The transgenic expression of hHPX was confirmed by short- and long-term experiments assessing messenger RNA and protein expression levels. Messenger RNA expression was analyzed via RT-PCR in liver samples using primers specific for the hHPX sequence. As reference genes, Calr and Hsp90b1 were selected from a repository of housekeeping genes.14 Protein expression levels were determined using ELISAs specific for hHPX. Additionally, protein expression was confirmed through western blot analysis of liver samples. The transgenic expression of mHPX was confirmed by comparing pretreatment and posttreatment levels of circulating HPX using ELISA, as well as by RT-PCR analysis of liver samples.

Clinical parameters of safety and efficacy

Efficacy parameters included (1) induction of the expression of HO, (2) weight gain, and (3) modulation of the inflammatory profile. The expression of HO-1 was evaluated in liver samples by western blot. Weight gain was tracked every 2 weeks and expressed as a ratio relative to baseline weight (Δ weight). Plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines were performed using a customized Luminex immunoassay (MCYTOMAG-70K-06 multiplex panel, Merck) for interleukin 6 (IL-6), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), on a Bio-Plex 200 instrument (Bio-Rad).

Safety parameters included biomarkers of tissue damage, complete blood counts, and histological assessments. Liver toxicity was evaluated by measuring liver enzymes, specifically aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase, whereas kidney toxicity was assessed by creatinine levels in serum samples. Hematological toxicity was examined through complete blood counts using automated analyzers. Given that excessive iron delivery to liver cells can lead to toxicity, liver damage was also assessed through hematoxylin and eosin staining, and the presence of inflammation, fibrosis, and necrosis was evaluated by 2 independent, blinded observers. The severity of necrosis and fibrosis was graded using 2 previously established scoring systems.15,16

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean and median with interquartile ranges. Group comparisons were made using either the Mann-Whitney U test or the Wilcoxon test. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

rAAV8-hHPX induced the expression of hHPX in Townes mice but at low circulating levels

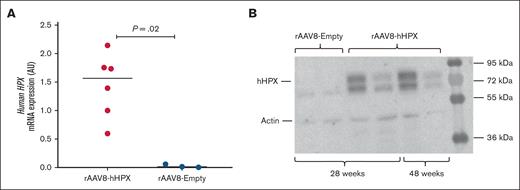

Table 1 provides an overview of the animal experiments. We have previously shown that the rAAV8-hHPX vector is capable of expressing hHPX in C57BL/6J mice in a dose-dependent manner, reaching levels up 2.4 mg/mL, corresponding to values twofold higher than endogenous values, and that expression was sustained for up to 26 weeks.12 We were able to confirm the liver expression of hHPX in Townes mice by RT-PCR and western blot for up to 48 weeks after gene transfer (Figure 1A-B). Circulating levels of HPX were detected in 4 of 13 mice transduced with rAAV8-hHPX, which presented a median concentration of 0.25 mg/mL. None of the control mice transduced with the rAAV8-Empty vector presented detectable expression levels by any of the techniques.

Overview of animal model experiments

| Mouse model . | C57Bl/6J . | Townes . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vector | rAVV8-hHPX | rAVV8-mHPX | rAVV8-hHPX | rAVV8-mHPX |

| Follow-up, weeks | 2 | 4 | 48 | 30 |

| Parameters | L | HPX, L | W, CBC, H, HPX, L | W, C, CBC, B, HPX, L |

| Total n of mice | 1 | 10 | 7 | 16 |

| Mouse model . | C57Bl/6J . | Townes . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vector | rAVV8-hHPX | rAVV8-mHPX | rAVV8-hHPX | rAVV8-mHPX |

| Follow-up, weeks | 2 | 4 | 48 | 30 |

| Parameters | L | HPX, L | W, CBC, H, HPX, L | W, C, CBC, B, HPX, L |

| Total n of mice | 1 | 10 | 7 | 16 |

B, biochemistry; C, inflammatory cytokines; CBC, complete blood count; H, histology; L, analysis of liver gene/protein expression; rAVV8, recombinant AVV8; W, weight.

hHPX levels in Townes mice transduced with the rAAV8-hHPX vector. (A) mRNA expression of hHPX in liver samples of mice transduced with 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-hHPX vector or rAAV8-Empty vector (n = 3 to 6 per group); (B) protein expression of hHPX by western blot in liver samples of mice transduced with 2 × 1013 vg/kg rAAV8-hHPX vector (n = 4) or with rAAV8-Empty vector (n = 2); the results are presented as median and P values are from the Mann-Whitney U test. mRNA, messenger RNA.

hHPX levels in Townes mice transduced with the rAAV8-hHPX vector. (A) mRNA expression of hHPX in liver samples of mice transduced with 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-hHPX vector or rAAV8-Empty vector (n = 3 to 6 per group); (B) protein expression of hHPX by western blot in liver samples of mice transduced with 2 × 1013 vg/kg rAAV8-hHPX vector (n = 4) or with rAAV8-Empty vector (n = 2); the results are presented as median and P values are from the Mann-Whitney U test. mRNA, messenger RNA.

rAAV8-mHPX induces the expression of mHPX in Townes mice but did not promote further increases in circulating levels

To optimize expression, and to circumvent the potential development of cross-species antibodies we produced a vector carrying the murine version of HPX cDNA. We first confirmed the efficacy of the rAAV8-mHPX vector by transducing C57BL/6J mice with 2 increasing doses of the rAAV8-mHPX vector or the rAAV8-Empty vector and then measuring the circulating levels of HPX using ELISA (Figure 2). We then used this vector in Townes mice. As shown in Figure 3, we were able to confirm a significant increase in the expression of mHPX at the transcriptional level (Figure 3A), but plasma mHPX levels remained low (Figure 3B).

Plasma levels of murine HPX at baseline, and 2 and 4 weeks of C57BL/6J mice transduced with the rAAV8-mHPX vector or control vector (n = 3-4 per group). The dotted band indicates the normal mHPX values found in C57BL/6J mice. One-way analysis of variance test.

Plasma levels of murine HPX at baseline, and 2 and 4 weeks of C57BL/6J mice transduced with the rAAV8-mHPX vector or control vector (n = 3-4 per group). The dotted band indicates the normal mHPX values found in C57BL/6J mice. One-way analysis of variance test.

mHPX levels in Townes mice transduced with the rAAV8-mHPX vector. (A) mRNA expression of mHPX in liver samples of mice transduced with 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-mHPX vector (n = 8 to 13 per group). (B) mHPX levels in mouse plasma before vector infusion (basal), 8 and 28 weeks after infusion with 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-mHPX vector (n = 9 to 14 per group). The results are presented as median and mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and P values are from the Mann-Whitney U test. AU, arbitrary unit.

mHPX levels in Townes mice transduced with the rAAV8-mHPX vector. (A) mRNA expression of mHPX in liver samples of mice transduced with 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-mHPX vector (n = 8 to 13 per group). (B) mHPX levels in mouse plasma before vector infusion (basal), 8 and 28 weeks after infusion with 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-mHPX vector (n = 9 to 14 per group). The results are presented as median and mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and P values are from the Mann-Whitney U test. AU, arbitrary unit.

Efficacy parameters of the gene transfer of HPX to Townes mice

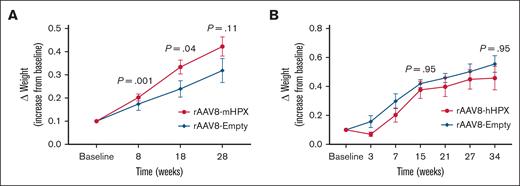

One of the efficacy parameters evaluated was weight gain in Townes mice, as a surrogate marker of disease progression. Townes mice that received the vector expressing the murine version of HPX (rAAV8-mHPX) presented a significantly higher weight gain, which was evident after 8 weeks of vector infusion (Figure 4A), than mice that received the empty control vector. Of note, no significant difference could be observed with the rAAV8-hHPX vector (hHPX; Figure 4B).

Variation in weight gain of Townes mice. (A) Mice transduced with 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-mHPX vector (n = 15) compared with mice treated with the control vector (n = 10); (B) mice transduced with 2 × 1013 vg/kg rAAV8-hHPX vector (n = 5) compared with mice treated with the control vector (n = 3). The results are expressed as weight gain (g) per basal weight. The results are presented as mean ± SEM, and P values are from the Mann-Whitney U test.

Variation in weight gain of Townes mice. (A) Mice transduced with 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-mHPX vector (n = 15) compared with mice treated with the control vector (n = 10); (B) mice transduced with 2 × 1013 vg/kg rAAV8-hHPX vector (n = 5) compared with mice treated with the control vector (n = 3). The results are expressed as weight gain (g) per basal weight. The results are presented as mean ± SEM, and P values are from the Mann-Whitney U test.

As a surrogate marker of efficacy, considering the proinflammatory nature of SCD, we also evaluated the inflammatory profile of Townes mice that received the murine vector. After 28 weeks of rAAV8-mHPX transduction, significantly lower levels of TNF-α were observed (Figure 5A) than in mice that received the control vector. No significant differences were observed in the plasma levels of IL-6, CXCL1, and VEGF (Figure 5B-D).

Inflammation biomarkers. Plasma levels of (A) TNF-α, (B) IL-6, (C) KC, and (D) VEGF in Townes mice transduced with rAAV8-mHPX (n = 4 to 10). Mann-Whitney U test. KC, CXCL1.

Inflammation biomarkers. Plasma levels of (A) TNF-α, (B) IL-6, (C) KC, and (D) VEGF in Townes mice transduced with rAAV8-mHPX (n = 4 to 10). Mann-Whitney U test. KC, CXCL1.

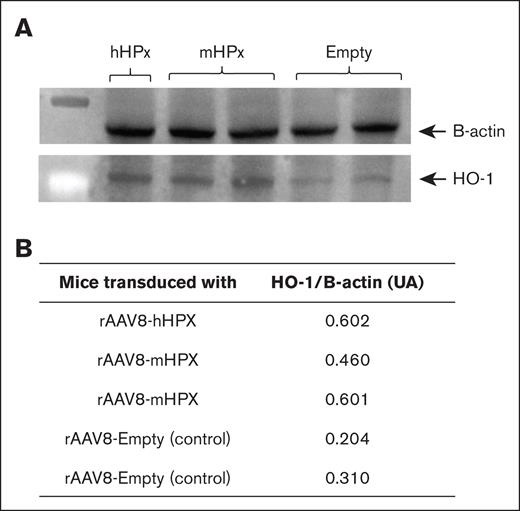

Another equally important efficacy parameter defined a priori for our strategy was the expression of HO-1, an enzyme induced by the shuttling of heme to liver cells, with demonstrated beneficial properties in the context of SCD.7 To address whether our gene transfer of HPC strategy was capable of increasing the delivery of heme to liver cells, C57BL/6J mice were challenged with an overload of heme (70 μM/kg), and liver samples were obtained after 1 hour. By analyzing protein expression, we observed that the animals that received either the rAAV8-hHPX vector or the rAAV8-mHPX vector showed higher levels of HO-1 than mice that received rAAV8-Empty vector (Figure 6).

Western blot analysis of HO-1 expression in the liver of C57Bl/6J mice transduced with 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-hHPX or rAAV8-mHPX vector and challenged with 70 μM/kg of heme. Samples were obtained 1 hour after infusion. (A) Lower protein expression is demonstrated in gels and expressed as AUs (B) after densitometry.

Western blot analysis of HO-1 expression in the liver of C57Bl/6J mice transduced with 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-hHPX or rAAV8-mHPX vector and challenged with 70 μM/kg of heme. Samples were obtained 1 hour after infusion. (A) Lower protein expression is demonstrated in gels and expressed as AUs (B) after densitometry.

Safety parameters of the gene transfer of HPX to Townes mice

Safety parameters included hematological (Hb, and leukocyte and platelet counts; Table 2) and biochemical (liver enzymes, creatinine, and urea) parameters (Table 3). No significant differences were observed between the groups.

Hematological parameters of Townes mice transduced with 2 × 1013 vg/kg rAAV8-hHPX or 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-mHPX vector compared with mice treated with the control vector

| . | rAAV8-mHPX (n = 16) . | rAAV8-Empty (n = 10) . | P value∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28th Week | |||

| Leukocytes (×103/μL) | 12.0 (8.5-14.4) | 12.1 (9.4-17.2) | .84 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 4.5 (4.0-5.5) | 4.5 (4.2-6.2) | .36 |

| Platelets (×103/μL) | 810 (573-1063) | 865 (735-1090) | .46 |

| . | rAAV8-mHPX (n = 16) . | rAAV8-Empty (n = 10) . | P value∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28th Week | |||

| Leukocytes (×103/μL) | 12.0 (8.5-14.4) | 12.1 (9.4-17.2) | .84 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 4.5 (4.0-5.5) | 4.5 (4.2-6.2) | .36 |

| Platelets (×103/μL) | 810 (573-1063) | 865 (735-1090) | .46 |

| . | rAAV8-hHPX (n = 7) . | rAAV8-Empty (n = 3) . | P value∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 34th Week | |||

| Leukocytes (×103/μL) | 7.1 (4.1-9.0) | 10.1 (5.0-18.7) | .47 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 4.2 (3.2-5.6) | 4.0 (2.3-5.2) | .77 |

| Platelets (×103/μL) | 392 (302-698) | 455 (235-663) | .91 |

| . | rAAV8-hHPX (n = 7) . | rAAV8-Empty (n = 3) . | P value∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 34th Week | |||

| Leukocytes (×103/μL) | 7.1 (4.1-9.0) | 10.1 (5.0-18.7) | .47 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 4.2 (3.2-5.6) | 4.0 (2.3-5.2) | .77 |

| Platelets (×103/μL) | 392 (302-698) | 455 (235-663) | .91 |

Results shown as median and interquartile range.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Biochemical parameters of Townes mice treated with 1 × 1014 vg/kg rAAV8-mHPX or control vector

| . | rAAV8-mHPX . | rAAV8-Empty . | P value∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (U/L) | 111.0 (52.0-212.0) | 61.0 (30.0-85.7) | .07 |

| AST (U/L) | 81.0 (67.0-122.0) | 74.5 (36.2-80.7) | .09 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.09 (0.09-0.12) | 0.11 (0.09-0.11) | .40 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 58.0 (51.0-62.0) | 58.0 (53.0-64.7) | .53 |

| . | rAAV8-mHPX . | rAAV8-Empty . | P value∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (U/L) | 111.0 (52.0-212.0) | 61.0 (30.0-85.7) | .07 |

| AST (U/L) | 81.0 (67.0-122.0) | 74.5 (36.2-80.7) | .09 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.09 (0.09-0.12) | 0.11 (0.09-0.11) | .40 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 58.0 (51.0-62.0) | 58.0 (53.0-64.7) | .53 |

Results shown as median and interquartile range; n = 10-16 per group.

ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Mann-Whitney U test.

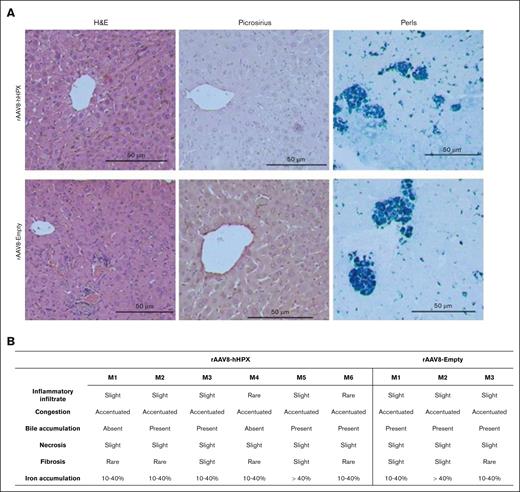

Finally, considering that the induction of HPX expression in the context of heme overload could lead to the shuttling of toxic levels of heme to liver cells, we also explored the safety of our strategy by histological analysis of liver samples from a subgroup of Townes mice that received 2 × 1013 of rAAV8-hHPX, after 20 weeks of transduction. As shown in Figure 7, alterations compatible with SCD (congestion and marked accumulation of bile and iron) were observed in both groups (active or empty vector), whereas inflammation and necrosis were rare (Figure 7).

Liver histology. (A) Representative images of H&E stained liver sections from Townes mice treated with rAAV8-hHPX or control (rAAV8-Empty) vectors. No evidence of inflammation, fibrosis, or necrosis were observed. Original magnification ×400. (B) Results from individual mice; n = 3 to 6 per group. Analysis performed by 2 blinded observers. Single-cell necrosis denotes sparse and rare events. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; M, mouse.

Liver histology. (A) Representative images of H&E stained liver sections from Townes mice treated with rAAV8-hHPX or control (rAAV8-Empty) vectors. No evidence of inflammation, fibrosis, or necrosis were observed. Original magnification ×400. (B) Results from individual mice; n = 3 to 6 per group. Analysis performed by 2 blinded observers. Single-cell necrosis denotes sparse and rare events. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; M, mouse.

Discussion

Free heme, capable of activating various compartments of innate immunity, is currently considered to be an important element in the pathogenesis of SCD.2,17-20 HPX is responsible for removing heme from circulation and preventing it from exerting toxic effects. In our previous work, we demonstrated that the rAAV8-hHPX vector was capable of expressing hHPX in a sustained and dose-dependent manner in C57BL/6J mice, in addition to demonstrating its efficacy and without signs of toxicity.12 The next step was to test this vector in an animal model of SCD, which mimics the clinical conditions of a patient with the disease.

We demonstrated the expression of hHPX for up to 48 weeks in Townes mice using the rAAV8-hHPX vector. Although expression was confirmed at the transcriptional and protein level, we were unable to observe an increase in plasma levels of hHPX. In our previous studies, using a heme infusion model and a Phenylhydrazine (PHZ)-induced hemolysis model, we showed the consumption of hHPX, which demonstrated the functionality of the exogenous protein and indicated that the lack of plasma detection of the protein in SCD models is probably due to the intense hemolysis, which leads to large releases of free heme, resulting in almost total consumption of plasma HPX.4,12,21

Although the human form of HPX was chosen to facilitate its detection by ELISA, we acknowledge that expressing a human protein in a murine model can potentially negatively affect its biological function. In this regard, differences in the posttranslational processing of hHPX can lead to lower expression and/or impaired biological function. Furthermore, although we did not detect signs of neutralizing antibodies to hHPX (data not shown), we cannot rule it out that this is a possibility.22 These possibilities were the rational for moving to a new vector capable of expressing mHPX, and they can potentially explain the lack of biological effects of the vector delivering hHPX compared with the vector delivering mHPX. Therefore, we decided to develop a new vector capable of expressing mHPX as a way of further optimizing expression, given the challenge of HPX consumption in the SCD model, as well as to minimize the risk of immunogenicity to the protein. However, although we were able to demonstrate the expression at the transcriptional level in liver samples of transduced mice, we did not obtain significant expression of circulating levels of mHPX in the Townes mouse model, even with a higher dose, which proved capable of inducing expression in C57Bl/6J mice.

Although we observed stable levels of plasma HPX in C57Bl/6J mice, the same was not the case in Townes mice. Studies have shown that due to intense hemolysis in these animals, free heme levels are elevated, leading to depletion of plasma HPX.23 Our hypothesis is that the low HPX levels found are due to HPX consumption, which is intense in this animal model of SCD, in which hemolytic activity is very high, as evidenced by Hb levels of ∼5 to 6 g/dL. Thus, we hypothesized that the failure to restore normal circulating HPX levels did not exclude its biological effect, leading us to explore efficacy parameters.

HO-1 is an important enzyme with anti-inflammatory properties. When levels of free heme are increased, there is an increase in the expression of HO-1, which will metabolize this heme when it is internalized by HPX, catabolizing it into iron, CO2, and biliverdin.24,25 The beneficial effect of HO-1 induction in animal models of SCD has been extensively demonstrated.7,26 Our hypothesis was that, by increasing the availability of HPX, more heme would be internalized, which would lead to an increase in HO-1 expression. Although we were not able to observe this modulation in Townes mice, possibly due to the baseline high levels of heme delivered to liver cells due to their sustained hemolysis, we decided to use an acute heme infusion model and observed that the animals that received the vector (human or murine) expressed more HO-1 than those that received the control vector, confirming our initial hypothesis. As mentioned earlier, the lack of positive modulation of HO-1 expression in Townes mice may be explained by the constant hemolysis and high levels of heme, which can cause a plateau in HO-1 expression.

One of the especially relevant parameters in animal models of SCD is weight gain, because a chronic disease such as SCD can affect this gain due to the intense catabolism associated with it.27 Although we observed no difference in weight gain in the animals that received the human vector, this difference can be seen in the animals that received the vector expressing mHPX, observing a greater weight gain in the animals treated with the active vector than in those that received the control vector. We consider this finding as a relevant surrogate marker of the efficacy of delivering exogenous HPX by gene transfer to Townes mice.

Chronic inflammation is a well-known feature of SCD, and several biomarkers are associated with the clinical course of the disease, so we decided to investigate some of them. No differences were observed in the plasma levels of IL-6, CXCL1, and VEGF. However, the mice that received the murine vector had lower levels of TNF-α. TNF-α is a transmembrane protein involved in systemic inflammation and the acute phase reaction. Studies have shown that it is increased in patients with SCD, indicating a persistent inflammatory process.28,29 The low levels of TNF-α indicate a decrease in the inflammatory process characteristic of this model, suggesting that increasing the availability of HPX can downregulate at least some of the mediators of the inflammatory cascade observed in SCD.

Finally, we also analyzed hematological and biochemical biomarkers as safety parameters and observed no changes in mice that received the active vector. One important concern we had was that increasing the availability of HPX could result in iron-mediated toxicity, because this ion is one of the catabolites of heme after the action of HO-1 inside the cell. No evidence of this possibility was observed in biochemical analyses.

Liver fibrosis has been shown in animal models of SCD, which is attributed to the inflammatory cascade of events associated with this condition.30 Moreover, increasing HPX availability could increase heme internalization and, consequently, increase inflammation and fibrosis. Notably, no evidence of inflammation or hemolysis was observed in any of the experimental groups.

HPX is a protein expressed mainly in the liver. Therefore, we chose AAV8, a hepatotropic vector, coupled with a liver-specific promoter, to make expression as liver-restricted as possible. Nonetheless, the fact that we did not evaluate off-target expression in other tissues should be viewed as a limitation of our study. Furthermore, we did not evaluate the increase in mHPX at the protein level, which would provide us with more information about protein expression levels before consumption.

In 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first 2 gene therapies for the treatment of sickle cell anemia: Casgevy, which uses CRISPR/CRISPR–associated protein 9 genome editing technology to increase the production of fetal Hb; and Lyfgenia, which uses a viral vector based on a lentivirus to increase the production of HbA. Both therapies use the patient’s own blood stem cells, which are modified and reintroduced back into the patient.31-33 Our study illustrates, at a significant preliminary stage, an alternative strategy of tackling an indirect but relevant consequence of the presence of the causative mutation of sickle cell anemia. Although preliminary, our results confirm previous data using an alternative gene transfer strategy.34 We believe that our results contribute, with additional knowledge, to the field of alternative therapeutic strategies for SCD, as well as for other conditions associated with hemolysis and excess heme release.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our vector was able to express hHPX and increase the expression of mHPX in an animal model of sickle cell anemia, without showing signs of toxicity. Although we were unable to restore plasma levels of HPX in Townes mice, which may be explained by the intense hemolysis observed in this model, animals that received the rAAV8-mHPX vector presented indirect signs that disease severity was modulated (better weight gain and lower levels of a critical inflammatory biomarker), without signs of hematological or liver toxicity.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation, grants 2018/23484-7, 2019/18886-1, and 2022/13216-0; and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior, Brazil and the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development grant 442721/2020-0.

Authorship

Contribution: F.D.L. contributed to the study design, obtained and processed samples from experimental animals, performed biochemical/hematological assays, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), real-time polymerase chain reaction, western blot, and histology analyses, analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript; C.R.P.D.M. obtained samples from experimental animals and performed ELISA and Luminex tests; I.T.B.-J. obtained samples from experimental animals and analyzed data; H.B.A. and M.J.A.S. conducted western blot test and analyzed data; F.F.C. oversaw and provided resources and infrastructure for all tests; E.V.D.P designed the study, oversaw and provided resources and infrastructure for all tests, contributed to data analysis, and drafted the manuscript; and all authors revised and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Franciele de Lima, Laboratory of Hemostasis and Inflammation, School of Medical Sciences, University of Campinas, Rua Carlos Chagas 480, Campinas, SP 13083-878, Brazil; email: franciele_lima@yahoo.com.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Franciele de Lima (franciele_lima@yahoo.com).