Abstract

Accurate imaging of lymphoma is essential for optimal management. Positron emission tomography (PET), by providing both anatomic and functional information, is fundamentally altering staging, monitoring of response, response assessment, and choice of treatment modality for lymphomas, including Hodgkin lymphoma. This imaging technique, when used carefully in conjunction with standard testing, increases the sensitivity of lesion detection, provides an opportunity to monitor the quality of response during treatment, permits separation of fibronecrotic scar tissue from viable tumor, and adds prognostic information. PET has become integral to modern lymphoma management, but as a relatively new diagnostic technique, it is still being studied and neither its full potential nor its major limitations are fully understood. Discussed herein are recent observations from clinical trials and single-center experiences with PET to explore its advantages and limitations from a clinician's point of view.

Introduction

Appropriate imaging is an integral part of oncologic management. This is particularly true of Hodgkin lymphoma, in which the accurate assessment of the initial extent of disease determines the optimal treatment plan and monitoring for treatment response and guides treatment duration and choice of therapeutic modality. Computed tomography (CT) of the neck, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis has become the standard imaging technique to determine initial disease extent, to monitor disease regression during treatment, and to assess completeness of response at the conclusion of planned therapy. However, CT scanning has substantial limitations. It cannot detect small lesions, especially within or at the borders of solid organs and, even more importantly, it can only assess size and provides no information about cellular function. This latter limitation makes assessment of lymph nodes in the range of 0.5-1.5 cm problematic because CT scanning cannot reliably distinguish normal nodes from those involved with lymphoma, nor can CT scanning determine whether a residual mass is composed of fibronecrotic scar tissue or persistent viable neoplastic cells. Positron emission tomography (PET), which uses fluorinated deoxyglucose, partially addresses these inadequacies and provides a major improvement in imaging capability for Hodgkin lymphoma. It has been further improved by the development of integrated PET/CT scanners. Such modern equipment allows enhanced localization of fluorinated deoxyglucose uptake, improving both sensitivity and specificity and making current PET/CT scanners highly accurate, state-of-the-art equipment. As with any new technique, however, integration of PET/CT into standard staging and management of lymphomas requires careful assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of this new imaging modality.

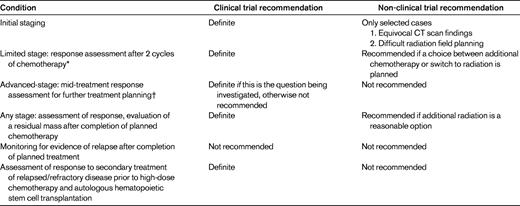

PET/CT scanning can provide helpful guidance for the management of Hodgkin lymphoma at several points in the patient's overall assessment and treatment, including staging, monitoring disease response during treatment, and determining completeness of treatment response at the end of the planned intervention (Table 1). PET/CT scanning may also provide useful information concerning prognosis both during primary treatment and during secondary treatment for relapsed or refractory disease. However, optimal use of PET/CT at each of these decision points requires knowledge of its potential pitfalls and limitations.

Staging

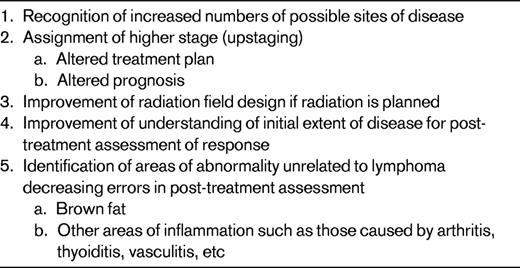

PET/CT is more sensitive than any other imaging technique at detecting potential metastatic deposits of Hodgkin lymphoma during initial staging (Table 2). The increased sensitivity of PET and PET/CT theoretically improves both the quality and the accuracy of staging (Table 3). Typically, PET/CT identifies 25%-30% more lesions than are found with conventional methods, which may lead to assignment to a higher stage, potentially altering the planned treatment. The utility of such information, however, may be relatively limited, especially today when almost all patients with Hodgkin lymphoma receive at least some systemic treatment regardless of stage. For example, if a patient with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma (stage III or IV) is to be treated with an extended course of chemotherapy, it may not matter that more sites of involvement are recognized. Conversely, if radiation is a part of the planned treatment, as is common with limited-stage Hodgkin lymphoma, PET/CT scanning may guide the design, shape, and dosimetry of involved field or involved nodal radiotherapy even in the absence of upstaging. Therefore, it remains essential to consider the context in which the PET/CT scanning is being contemplated.

Presently, using only CT scanning, patients with good-prognosis, limited-stage Hodgkin lymphoma (low bulk (< 10 cm stage IA or IIA) have a > 95% likelihood of cure with brief chemotherapy and involved field radiation6 because systemic control of micrometastatic disease is provided by the chemotherapy and local control is provided by the radiation. Such patients are at risk of overtreatment if upstaged solely on the basis of PET/CT scanning, which may lead to their being given an extended course of chemotherapy. This latter observation means that, outside of a clinical trial, patients found to have unequivocally limited-stage Hodgkin lymphoma based on full-body CT scanning do not need PET/CT scanning. If equivocal findings have emerged during CT scan–based evaluation, PET/CT may provide useful clarification. Finally, PET/CT scanning is now recommended as part of staging for all patients with Hodgkin lymphoma being assessed in clinical trials,7,8 in which the additional uniformity of assessment that it confers is of obvious benefit, or when the utility of PET/CT scanning is one of the questions being addressed by the clinical trial.

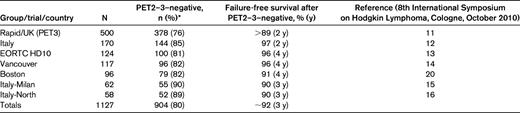

Limited stage: response assessment after 2 cycles of chemotherapy

With currently available treatment options, patients with limited-stage (low bulk < 10 cm stage IA or IIA) Hodgkin lymphoma have a > 95% likelihood of cure with primary treatment. For this reason, care must be taken to avoid overtreatment with subsequent risk of potentially avoidable late toxicity. The National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group HD6 trial demonstrated that approximately 50% of patients who reach a complete response by CT scanning after 2 cycles of adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) can complete treatment with 2 more cycles of ABVD and have a very high likelihood of cure without radiotherapy.9,10 Those with only a partial response by CT scanning after 2 cycles of ABVD have an 80% likelihood of cure with continuation of ABVD, raising the question of whether the 20% who are destined to relapse despite continued chemotherapy might be identified with functional imaging and could therefore be offered radiotherapy instead. Results from 8 different treatment centers or groups examining experience in over 1100 patients, as reported to the 8th International Symposium on Hodgkin Lymphoma in October 2010 and summarized in Table 4, demonstrate the excellent negative predictive value of PET/CT scanning for such patients. After 2 or 3 cycles of ABVD, approximately 80% of patients quite consistently reach a PET/CT–negative response and have a 95% progression-free survival whether subsequently treated with radiotherapy or additional chemotherapy.

Presently, Hodgkin lymphoma experts are divided in their interpretation of these results. Some prefer to switch all patients to radiation after 2 cycles of chemotherapy regardless of CT or PET/CT scan results, in which case there is no need for the PET/CT scan. Others choose to use the PET/CT scan to separate the patients into 2 groups, planning to have the 80% with a negative PET/CT scan complete treatment with 2 more cycles of ABVD and the 20% with a positive PET/CT scan switch to radiotherapy. This strategy is currently being tested in prospective clinical trials. Such trials, however, will need to be carefully interpreted. Using a negative PET/CT to identify a group of patients who can be managed without radiotherapy will lead to a lower progression-free survival than if those patients were switched to radiotherapy. However, a modestly lower progression-free survival may be quite acceptable to avoid putting the entire population at risk of late toxicity of radiotherapy, knowing that highly effective secondary treatment is available for the small number who will relapse. Indeed, the RAPID trial of 3 cycles of ABVD after which PET/CT–negative patients are randomized to observation versus involved field radiation currently being conducted in the United Kingdom is powered around the proposition that a progression-free survival that is 5%-7% inferior is acceptable if radiation can be avoided.11

Advanced stage: mid-treatment response assessment for further treatment planning

The initial observation by Gallamini and others that PET/CT scanning after 2 cycles of chemotherapy could strongly predict treatment outcome for patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma and eliminated the impact of known clinical prognostic factors was greeted with great excitement.17,18 However, subsequent observations have tempered this enthusiasm. Mid-treatment PET/CT scans have proven difficult to interpret reproducibly,18–21 and treatment outcome has not proven so strongly dichotomous in subsequent testing.18–21 Whereas it remains clear that patients who have a persistently positive PET/CT scan after a few cycles of chemotherapy are more likely to relapse than those with a negative scan, there is equally clearly a large subset of patients who can be cured by simply continuing the planned chemotherapy despite a positive PET/CT scan, making it inappropriate to endorse switching to more intensive, and therefore more toxic but not necessarily more effective, treatment solely based on the mid-treatment PET/CT scan result. Until currently accruing clinical trials testing this proposition are analyzed, altering treatment based on mid-treatment PET/CT scanning cannot be recommended outside of clinical trials and may expose patients to unjustifiably increased risk of acute and late toxicity without any guarantee that outcome will be improved.

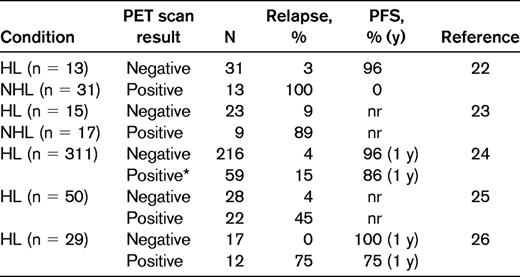

Assessment of response: evaluation of a residual mass after completion of planned chemotherapy

The goal of primary treatment of advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma is cure, which is most likely to be achieved if the treatment induces a complete response. Assessment of the completeness of response can often be accomplished with a combination of BM biopsy, if initially positive, and full-body CT scanning. No further assessment is needed if these tests are completely negative. However, many patients with Hodgkin lymphoma have residual masses visualized by CT scanning at the end of planned chemotherapy. As shown in the representative studies summarized in Table 5, PET/CT scanning is very helpful in distinguishing between persistent fibronecrotic scar tissue and potentially viable neoplastic tumor. A residual mass that is negative by PET/CT scan is quite unlikely to harbor persistent lymphoma, and a patient with such a mass can be judged to have reached a complete response.7,8 Treatment can be stopped because it is not unreasonable to extrapolate from previous CT scan–based observations that adding radiation after a complete response has been achieved with chemotherapy is of no proven value.27 After such a treatment algorithm at the British Columbia Cancer Agency, we have seen a 5-year progression-free survival of 92% in 151 patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma with a PET/CT negative residual mass after 6 cycles of ABVD. This result is very similar to that seen by the German Hodgkin Study Group in their HD15 trial, in which the 5-year progression-free survival was 92% in 540 patients with a negative PET/CT scan after a full course of chemotherapy.28 This observation even seems to be accurate in patients who had bulky disease at diagnosis. At our center, we have assessed 71 such patients (advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma with initial tumor mass ≥ 10 cm treated to PET/CT–negative complete response) managed without any further treatment after primary ABVD. With a median follow-up of 3.5 years for living patients, the projected 5-year progression-free survival is 90%. This strong negative predictive value of PET/CT scanning after chemotherapy for advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma provides practical guidance, indicating that treatment can be stopped and additional radiation or chemotherapy is unnecessary.

How to manage the ∼ 25% of patients with a positive PET/CT scan in a residual mass at the end of primary chemotherapy remains unresolved and will need to be addressed in future clinical trials. Undoubtedly, at least some such scans are falsely positive and no viable lymphoma persists. Alternatively, some scans are true positives, indicating that such patients harbor persistent lymphoma but it may not be possible to eradicate the lymphoma with the simple addition of radiation. A positive biopsy at least eliminates the question of false positivity, but it does not address the issue of whether such disease can be cured. A negative biopsy is of little help because it is more likely to be negative due to sampling error than to be truly representative. Presently, by default, many clinicians recommend radiation for patients with residual localized PET/CT–positive lesions even though it is potentially unnecessary (false positive) or ineffective (radiation-resistant disease) because of the intuitive appeal of using this potentially non-cross-resistant modality. However, the temptation to embark on intensified treatment for such patients should be tempered by recognition of its increased toxicity and lack of evidence of effectiveness. Fortunately, this use of intensified treatment is being examined in current clinical trials.

Monitoring for evidence of relapse after completion of planned treatment

High-dose chemotherapy supported by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can cure at least 50% of patients whose Hodgkin lymphoma recurs after primary chemotherapy. This observation has naturally led to a desire to monitor patients for relapse based on the supposition that early detection of relapse will increase the likelihood of cure with subsequent treatment. However, 2 observations should temper this optimism. First, at least 75% of relapses of Hodgkin lymphoma are detected by patients between scheduled reassessments and there is no evidence that relapse detected by planned surveillance leads to a better outcome than those detected by a patient's self-observation.29,30 Second, because most patients who reach a complete response after primary treatment do not relapse, the prior probability that any test will uncover relapse in an asymptomatic patient is very low. False-positive test results will be more common than truly positive results. A simple thought experiment demonstrates this principle. After a patient with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma has reached a complete remission, there is only a 20% chance the disease will ever recur, and this 20% risk is spread out over at least 5-10 years. Even in the high-risk early years of follow-up, the annual risk of relapse does not exceed 5% per year. Therefore, if a test is done twice yearly, the chance of detecting a relapse at the time of any given test is < 2.5%. If the test has a false-positive rate of just 5%, a low estimate for a test as sensitive as PET/CT scanning, each time the test is done, it is at least twice as likely to be falsely positive as to be truly positive. With the passage of time, the risk of relapse decreases steadily, but the risk of false positivity remains constant, steadily worsening the ratio of true to false positives. Therefore, the majority of results in such a situation will be false positives rather than detecting relapse. PET/CT scanning has no role in monitoring for relapse of Hodgkin lymphoma and exposes patients to unnecessary and anxiety-provoking radiation and complications of tests done to elucidate scan abnormalities mostly unrelated to the lymphoma.29,31

Assessment of response to secondary treatment of relapsed/refractory disease before high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Despite the high success rate of currently available treatments for Hodgkin lymphoma, ∼ 25% of patients have disease that is either refractory to primary treatment or relapses despite it. Today, most such patients are then treated with second-line chemotherapy, and those with responsive disease are offered high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Although effective, such treatment is also quite toxic, usually requiring hospitalization, and is associated with potentially life-threatening pancytopenia and other organ toxicities. Such toxic treatment can only be justified if it is likely to be effective. PET/CT scanning performed after secondary chemotherapy has been shown to be strongly prognostic in this situation,32–35 and has been advocated as a screening test to determine whether high-dose chemotherapy should be offered. However, PET/CT scanning has not been found sufficiently accurate in predicting outcome for such patients to be considered adequately reliable. Although a positive PET/CT scan immediately before the high-dose chemotherapy does predict a lower likelihood of cure, at least 7%-56% of patients with a positive scan remain free of subsequent relapse in the studies that have been reported.32–37 With no alternative reliably curative treatment available, it would not be prudent to abandon high-dose chemotherapy for these patients. Whether a strategy of turning to a different potentially non-cross-resistant chemotherapy regimen in another attempt to induce a negative PET/CT scan will lead to improved outcomes is untested. For the present, post-secondary chemotherapy assessment of response using PET/CT scanning cannot be recommended to screen patients for subsequent high-dose chemotherapy outside of clinical trials expressly testing this use.

Conclusions

Throughout its history, the management of Hodgkin lymphoma has been steadily improved by increasingly accurate imaging techniques. Currently, the use of PET/CT scanning is transforming lymphoma management at several crucial steps, ranging from staging through primary and secondary response assessment. The negative predictive value of PET/CT scanning can be very helpful in deciding whether radiation is necessary for the treatment of limited-stage Hodgkin lymphoma. Current clinical trials are refining our understanding of the usefulness of mid-treatment PET/CT scanning. Other trials may help clinicians identify patients whose response to secondary regimens has been of sufficient quality to ensure a high likelihood of cure with high-dose chemotherapy. Although in 2011, PET/CT scanning is already integral to optimal management of Hodgkin lymphoma, patients and clinicians can expect our understanding of its best use to continue to evolve and can help that evolution by participating in properly designed clinical trials addressing the best use of this powerful new imaging technique.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has received research funding from and has consulted for Seattle Genetics. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Joseph M. Connors, MD, FRCPC, Clinical Director, Centre for Lymphoid Cancer, BC Cancer Agency, Vancouver Centre, 600 West 10th Ave, Vancouver, V5Z 4E6 BC, Canada; Phone: (604) 877-6000, ext 2746; Fax: (604) 877-0585; e-mail: jconnors@bccancer.bc.ca.