Abstract

A 12-year-old girl with acute myeloid leukemia has completed her third cycle of chemotherapy and is in the hospital awaiting count recovery. Her platelet count today is 15 000 and, based on your institution's protocol, she should receive a prophylactic platelet transfusion. She has a history of allergic reactions to platelet transfusions and currently has no bleeding symptoms. The patient's mother questions the necessity of today's transfusion and asks what her daughter's risk of bleeding would be if the count is allowed to decrease lower before transfusing. You perform a literature search regarding the risk of bleeding with differing regimens for prophylactic platelet transfusions.

Introduction

Until the 1960s, hemorrhage was a leading cause of death in newly diagnosed leukemia patients.1 Prophylactic platelet transfusions were shown to decrease bleeding-related mortality.2 In the half-century since this discovery, clinicians and researchers have been trying to determine the optimal platelet transfusion regimen that minimizes both bleeding risk and transfusion exposures. There are several variables to such a regimen, including prophylactic threshold, platelet dose, and component preparation. Because the primary goal of platelet transfusions is to reduce the risk of hemorrhage, bleeding incidence and severity are often the primary or secondary objectives of these studies.

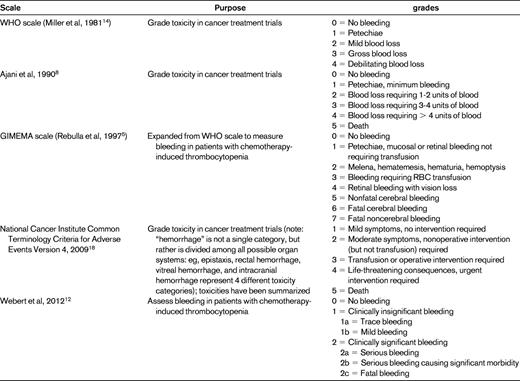

Currently, there is neither a universally agreed upon definition of clinically significant bleeding nor a consensus on the best method to quantify bleeding. Researchers report bleeding outcomes in a variety of ways, including the proportion of patients with bleeding, the percentage of thrombocytopenic days with bleeding, the highest bleeding grade, and the time to first bleed. Conclusions drawn regarding the relative safety and efficacy of a platelet transfusion regimen will vary depending on the type of analysis chosen by the investigators.3 Complicating these issues is the variety of scales that can be used to measure bleeding (Table 1). The most commonly used scale was created by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 19794 to standardize toxicity reporting in cancer treatment trials. The WHO scale is a broad categorical scale that leaves a significant amount of interpretation up to individual raters. Most researchers consider WHO grade 2 and above to be significant bleeding because of the relative rarity of WHO grades 3 and 4 bleeding (6%-9% and 1%-2%, respectively). However, grade 2 bleeding does not predict grades 3 and 4 bleeding, nor is there evidence that patients with WHO grade 2 bleeding have increased long-term morbidity or decreased survival compared with patients with grades 0 or 1 bleeding.

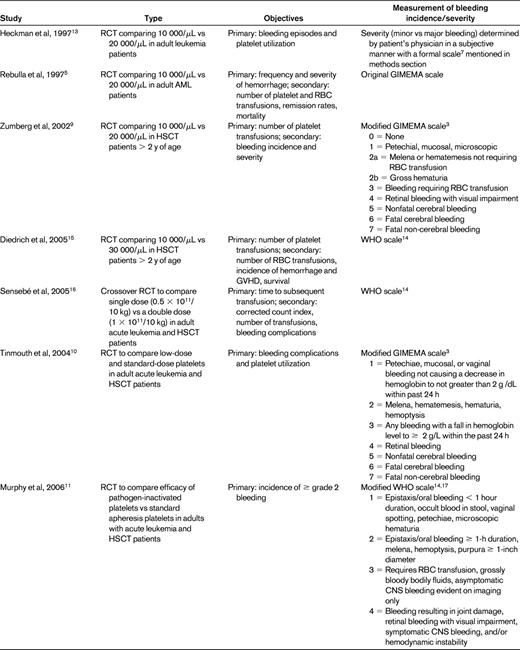

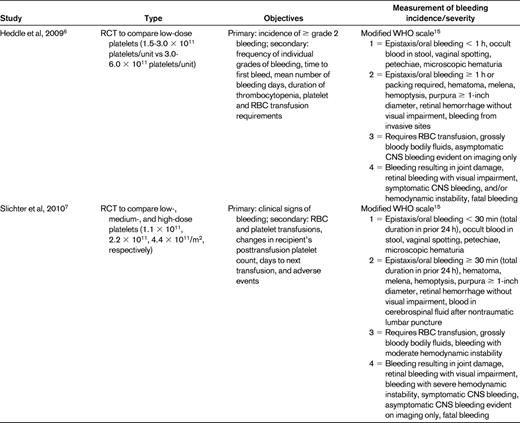

To examine the literature regarding the use of bleeding scores in recent platelet transfusion trials, we performed a PubMed search using the terms “platelet transfusion” and “bleeding” and “thrombocytopenia” with limits of “clinical trial” and got 49 hits. References chosen for this review include 9 randomized platelet transfusion trials in leukemia or stem cell transplantation patients in which bleeding was a primary or secondary outcome and that described the bleeding scale used in the methods section (Table 2).

The original Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell'Adulto (GIMEMA) scale was an expanded WHO scale described by Rebulla et al in 1997.5 The use of various scales by investigators makes it impossible to perform cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses. For example, because one trial defined > 60 minutes6 as a grade 2 nosebleed and another used > 30 minutes,7 a patient with a 45-minute nosebleed would have clinically significant bleeding in one trial, but not the other. An asymptomatic CNS bleed could be defined as grade 1 (of 4) in the Heckman trial,8 grade 5 (of 7) in the studies using the GIMEMA scale,3,9,10 grade 3 (of 4) in the Murphy11 and Heddle6 trials, and grade 4 (of 4) in the Slichter trial.7

We identified only one bleeding scale (designed by Webert et al) that has undergone psychometric evaluation to confirm validity and reliability.12 This scale was designed to separate clinically significant from clinically insignificant bleeding by determining whether medical or surgical intervention and/or increased level of care was needed. This definition of “significant” describes the type of bleeding that prophylactic transfusions are designed to prevent: that which exposes patients to the risks associated with medications, surgical procedures, long-term morbidity, and mortality.

None of the available bleeding scales take into account the impact that bleeding has on the quality of life of patients and families. Although daily nosebleeds lasting 15-20 minutes may not require intervention, they can be upsetting or disruptive to some patients. Therefore, combining the scale developed by Webert et al12 with quality-of-life measurements may provide the most complete representation of bleeding severity.

We rate the level of evidence for using the WHO scale and/or its variations in clinical research level 2C, because there are no studies comparing bleeding scores with regard to their completeness or accuracy in measuring clinically significant bleeding. There is insufficient evidence to determine which bleeding scale should be selected in the design of a clinical trial. This review highlights the difficulties created in this field of research due to the use of different scales to measure bleeding. As researchers move forward in creating clinical trials to mitigate bleeding incidence and severity, consistency in measuring bleeding across trials will improve the quality and standardization of research in this field by allowing for a common method of communicating and comparing results across studies.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.S.B. declares no competing financial interests. S.H.O. has consulted for GSK on topics not relevant to this paper. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Rachel S. Bercovitz, BloodCenter of Wisconsin, 638 N 18th St, Milwaukee, WI 53233; Phone: 414-937-6334; Fax: 414-933-6803; e-mail: rachel.bercovitz@bcw.edu.