Abstract

A 55-year-old man without prior medical problems presented to the emergency room with a 2-month history of progressive fatigue. Initial workup showed a hemoglobin level of 9.0 g/dL and an increased total protein level of 12.6 g/dL. Further testing revealed a normal serum calcium and creatinine, an IgG kappa paraprotein of 5.4 g/dL, and a Bence Jones proteinuria of 450 mg of kappa light chain in 24 hours. The bone marrow showed 60% plasma cells with normal cytogenetics and t(4;14), but no other associated genetic abnormalities by FISH. Skeletal survey and MRI of the spine were negative for myeloma bone disease. The patient's oncologist recently began therapy with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone and recommended the initiation of zoledronic acid monthly. The patient questions the benefit of this drug because he has no bone disease.

Introduction

Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclast-mediated osteolysis and are a standard therapy used for multiple myeloma (MM) patients with bone disease.1,2 Several large randomized studies have clearly shown a reduction in skeletal-related events (SREs) for such patients.3,4 Preclinical data indicate that the more potent amino-bisphosphonates zoledronic acid and pamidronate may induce apoptosis in myeloma cells, alter the BM microenvironment inhibiting myeloma cell growth, and act as immunomodulators mediating antitumor activity against myeloma.5 To make a decision to initiate bisphosphonate treatment for this patient with symptomatic myeloma but without bone disease, we focused our analysis on 2 critical questions. First, do bisphosphonates provide an overall survival (OS) advantage? Second, for MM patients without bone disease, does bisphosphonate use decrease the incidence of SREs?

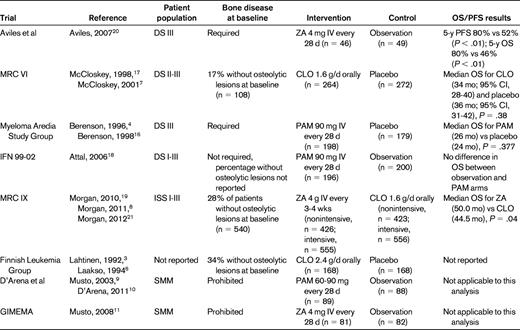

To determine the effect of bisphosphonate use on OS in MM patients, we identified 5 relevant randomized controlled clinical trials reporting OS data (Table 1). We were unable to locate any studies having clearly predefined end points addressing the development of SREs in MM patients without bone disease. Three studies reported specific SREs in subsets of patients without bone disease.6–8 We identified 2 studies with a patient population confined to smoldering MM (SMM) and used our analysis of these studies to investigate whether bisphosphonates reduced the incidence of SREs.9–11 Our literature search was conducted as follows. We combined the National Library of Medicine's Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms “Multiple Myeloma” AND “Diphosphonates” and limited the search to human randomized controlled clinical trials published in English from 1950 to June 2012. This yielded 49 citations. In total, 13 randomized controlled trials examining the use of bisphosphonates in MM or SMM were identified after we discarded trials that were not pertinent to bisphosphonates or MM (n = 6); purely translational biological studies (n = 5); review articles (n = 4); letters to the editor (n = 2); studies with dose finding, palliative, safety, or cost-benefit primary end points (n = 8); and trials of bisphosphonate drugs12–14 or routes of administration15 subsequently proven to not benefit patients with MM bone disease (n = 4). Seven citations were follow-ups of previously published studies.

Do bisphosphonates provide an OS advantage?

Improvement in OS would provide justification for the use of bisphosphonates for our patient. The Myeloma Aredia Study Group reported a placebo-controlled study evaluating the role of pamidronate 90 mg IV in 392 MM patients with bone disease. Although this study was not powered to address and did not detect a difference in OS, subgroup analysis of patients receiving second-line chemotherapy (n = 130) revealed a higher median OS for the pamidronate arm compared with placebo (21 vs 14 mo; P = .081). Multivariate analysis of this subgroup, including β-2-microglobulin and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, revealed a significant OS advantage with pamidronate therapy (P = .041).4,16 The Medical Research Council (MRC) VI Multiple Myeloma Trial reported no OS difference with the first-generation bisphosphonate, clodronate, compared with placebo. Despite this, subgroup analysis for patients lacking vertebral fractures revealed increased median OS with clodronate therapy (n = 73) compared with placebo (n = 80; 59 vs 37 mo, respectively; P = .004). The survival advantage remained significant when evaluated from plateau (P = .007) and from first relapse (P = .04).7,17 In contrast to the other studies for patients undergoing first- or second-line chemotherapy, the IFM 99-02 trial randomized patients to therapy after autologous transplantation: observation, pamidronate alone, or pamidronate + thalidomide maintenance. In IFM 99-02, all patients were low-risk (defined as those without or with only one of the following adverse factors: β-2-microglobulin > 3 mg/dL, or del 13q by FISH). Bisphosphonate randomization found that maintenance pamidronate did not improve event-free survival, relapse-free survival, or OS and did not decrease or delay SREs when initiated after autologous transplantation.18

The data from these 3 studies must be placed in context. The Myeloma Aredia Study Group trial was not powered to detect OS difference and included patients at several time intervals after diagnosis. MRC VI examined clodronate, which has now been shown to be inferior to zoledronic acid.19 IFM 99-02 initiated bisphosphonates after induction and high-dose therapy, a very different clinical situation than the patient in our example.

More recent data point toward increased OS for MM patients treated with zoledronic acid. A single-center study reported by Aviles et al showed a significant improvement in 5-year OS (80% vs 46%; P < .01) and event-free survival (80% vs 52%; P < .01) in zoledronic acid–treated patients compared with a randomized untreated control group.20 The MRC IX trial randomized 1960 newly diagnosed patients to zoledronic acid or clodronate and included patients receiving nonintensive therapy and those planned for high-dose therapy and autologous transplantation. That study demonstrated a survival advantage favoring the zoledronic acid group (hazard ratio = 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-0.96; P = .0118).19 Since the initial report was published, several hypotheses-generating subanalyses have been performed. Subgroup analysis of standard- and high-risk patients defined by FISH (high-risk patients had t(4;14), t(14;16), t(14;20), del 17p, and 1q+; standard-risk patients, everything else) showed that the survival impact was seen in all subgroups; however, the impact on SRE was predominately in the standard-risk group. The biological explanation for these differences is unclear, but could reflect the interactions with the microenvironment or differences in the rate of relapse and aggression of disease relapse.8 Interestingly, in the context of our patient, no OS benefit was seen in the group of patients lacking bone disease at presentation, whereas in the group with bone disease, zoledronic acid did confer a survival advantage (hazard ratio = 0.82; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.95; P = .0107).21 Despite this, the MRC IX data clearly point to an OS advantage for patients treated with zoledronic acid.

Does bisphosphonate use prevent the development of bone disease in MM patients without bone disease?

No clinical trials have been reported that investigate whether these agents reduce bone disease in bone disease-free symptomatic MM patients. Only MRC VI, MRC IX, and a Finnish Leukemia Group study have reported results of subsets of patients without bone disease. Given the lack of data, we extended our analysis to 2 randomized studies of bisphosphonate use in SMM, which by definition lacks bone disease but differs from our patient in that SMM does not require chemotherapeutic intervention.

The MRC VI subgroup of patients without vertebral fractures at study entry had fewer skeletal fractures with clodronate therapy compared with placebo (30 vs 50 events per 100 patient years; P < 0.02).17 MRC IX demonstrated that for patients without bone lesions at baseline, zoledronic acid decreased the risk of SRE compared with clodronate (10% vs 17%; P = .0068).8 The Finnish Leukemia Group study, which helped to establish the importance of bisphosphonates in reducing SREs for patients with MM,3,6 randomized 336 patients to clodronate or placebo for 24 months from the time of initial melphalan therapy. There was a significant difference in the proportion of patients with progression of osteolytic lesions in the clodronate group compared with placebo (12% vs 24%; P = .026). Within each arm, 34% of patients had no osteolytic lesions at baseline. For this subgroup, clodronate therapy was suggestive of a decrease in the development of new osteolytic lesions compared with placebo (2.6% vs 11.1%).6

A prospective, multicenter, randomized study with long-term follow-up reported by D'Arena et al randomized 177 SMM patients to monthly pamidronate or observation for 1 year.9,10 At a minimum of 5 years of follow-up for survivors, the pamidronate arm had a lower incidence of SRE at progression (39.2% vs 72.7%; P < .009).10 A more recent multicenter study of SMM was reported by the Italian Group for Adult Hematologic Diseases/Multiple Myeloma Working Party and the Italian Myeloma Network (GIMEMA), which randomized 163 patients to 12 months of zoledronic acid or to observation.11 The primary end point was 5-year progression-free survival, but study randomization was stopped early (70.8% of the planned sample size) after interim safety analysis raised concerns regarding osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ). At a median follow-up of 64.7 person-months, there were fewer SREs with zoledronic acid compared with control (55.5% vs 78.3%; P = .041).

Adverse consequences of therapy

In the MRC IX study, there was no difference in renal failure between the 2 bisphosphonate relevant groups. An excess of ONJ was seen with zoledronic acid, occurred in fewer than 4%-5% of patients, developed predominantly beyond 1 year, and in a competing risk model did not increase further after 3 years. This low rate undoubtedly reflects the introduction of the ONJ prevention guidelines, which should now be in general use.22

What are the implications for our patient?

For our patient with MM requiring therapy but lacking bone disease, we recommended that he be initiated on bisphosphonate therapy with zoledronic acid 4 mg IV every 3-4 weeks. This is a weak recommendation (grade 2B) relying primarily on the OS benefit of patients on zoledronic acid in the MRC IX study and the decreased SRE rate for patients without bone disease seen in the MRCIX and the Finnish studies. Pamidronate could be considered, but data are even more limited supporting its use in patients without bone disease at the start of therapy.23

Our recommendation must be qualified by several outstanding factors that future clinical trials may clarify. First, data quantifying the SRE incidence in patients initially without bone disease at the time of treatment are limited. MRC IX revealed that an SRE incidence of 17% in such patients treated with clodronate was reduced to 10% with zoledronic acid. This significant burden of SREs, which is likely to be even higher in patients receiving no bisphosphonate, is expected to be appreciably reduced by bisphosphonate therapy. Second, the optimal timing of bisphosphonates is unknown. Should therapy be withheld until careful monitoring reveals new onset of bone lesions? Or should it be initiated at disease progression? Based on the results with zoledronic acid showing a survival advantage, we can only surmise that their use at the time of initial therapy is advantageous. Similarly, questions regarding duration and schedule of administration must be addressed. Lastly, the use of bisphosphonates must be accompanied by appropriate dental prophylaxis and risk assessment by the treating physician. The true risk-benefit ratio in this population may be revealed by further studies. Despite these uncertainties, MM remains incurable and the nature of disease at relapse is unpredictable.

Based on the results of 2 randomized trials showing a lack of effect on time to progression, we conclude that bisphosphonates cannot be recommended in asymptomatic MM patients without bone disease who do not otherwise require systemic therapy (grade 2B). However, further clinical trials should be considered for high-risk SMM patients, because these trials did demonstrate a reduction in SREs at progression.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.J.M. has consulted for J&J, Celgene, and Novartis. F.L.L. declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: Consideration of bisphosphonate use for myeloma patients without osteolytic bone lesions.

Correspondence

Frederick L. Locke, Department of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Dr, FOB 3, Tampa, FL 33612; Phone: 813-745-8248; Fax: 813-745-8468; e-mail: frederick.locke@moffitt.org.