Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a curative therapeutic option for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). This is due to the combined effect of chemo/radiation therapy and the immunologic graft-versus-leukemia effect. The field of HSCT has benefited from advances in a variety of “fronts,” including our increasing ability to break the human leukocyte antigen barrier, which has led to greater access to transplantation. Furthermore, progress in the biologic, genetic, and pharmacologic arenas is creating a scenario where traditional borders between transplant and non-transplant therapies are less clear. This overlap is exemplified by new approaches to pharmacologic maintenance of remission strategies after HSCT. In addition, cellular adoptive immunotherapy has the potential to exploit narrowly targeted anti-tumor effects within or outside the allogeneic HSCT “frame,” holding the promise of avoiding off target side effects, such as graft-versus-host disease. Here we discuss these and other lines of active investigation designed to improve outcomes of HSCT for AML.

Learning Objectives

To review recent advances in allogeneic transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia

To discuss post-transplant interventions to prevent AML recurrence

Allogeneic transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is an established treatment option for a significant minority of patients with this disease. The proportion of patients receiving a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) has increased over the last decade due to a variety of reasons, including advances in supportive care, increased unrelated donor usage and availability, and the use of reduced intensity and reduced toxicity preparative regimens.1,2 Major causes of treatment failure, however, are treatment-related toxicity [graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), infections and chemo/radiation toxicity] and disease relapse. Reductions in the former have been associated with increased incidence of post-transplant AML recurrence, and relapse prevention is a major focus of preclinical and clinical research.

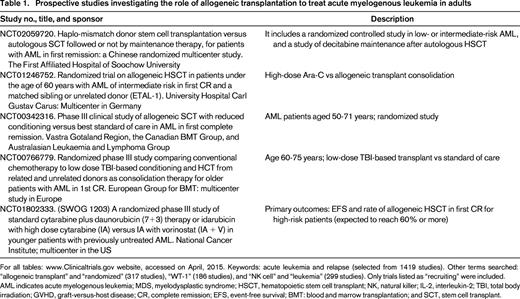

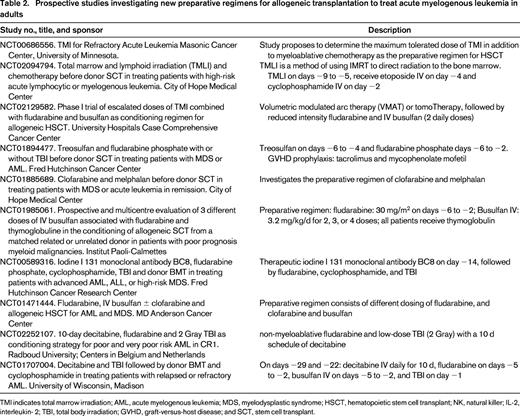

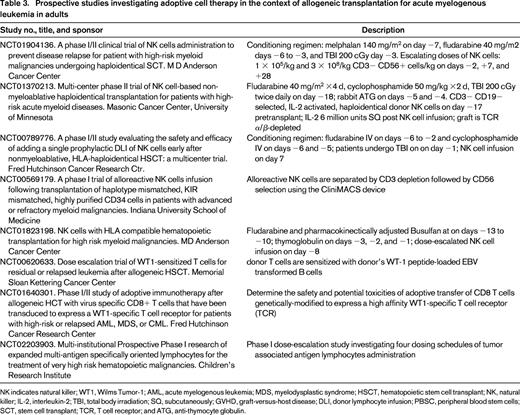

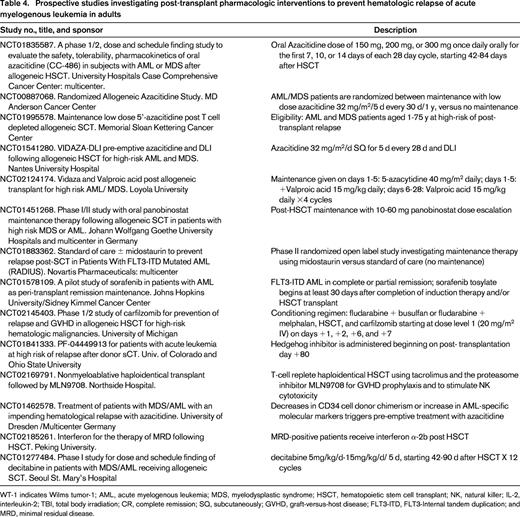

Given the broad topic of this review, I decided somewhat arbitrarily to divide the text in 3 sections, namely, pre-transplant, peri-transplant, and post-transplant interventions and developments. The other contributors of this educational session will discuss targeted therapies for AML, both in the transplant and non-transplant scenario, so this review will address “nonspecific” approaches in the HSCT process. I will not discuss autologous transplants, and will only superficially address the issue of indications for transplantation in AML.3,4 The tables associated with this review provide a detailed list of ongoing clinical studies in AML and HSCT listed on www.ClinicalTrials.gov. The intent is to provide an overview of trends in this rapidly changing field.

Pre-transplant

Improved biologic understanding of AML

The incorporation of genetic prognostic markers in addition to “classic” AML characteristics has led to better definition of high-risk disease, especially amongst patients with diploid cytogenetics.5-9 Presence of somatic mutations, such as nucleophosmin (NPM1) and fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), are now routinely considered when AML prognosis is estimated; presence of the latter with an internal tandem duplication (ITD) is considered an indication for allogeneic HSCT, for example. Monitoring for these and other mutations also provides a measurement of minimal or measurable residual disease (MRD). As in other scenarios, persistence of disease-related markers measured by molecular methods or multiparameter flow cytometry despite hematologic remission frequently heralds disease relapse.3,4,10-12

An example is provided by Walter et al who showed that the risk of AML relapse was increased 4.51 times for multiparameter flow cytometry MRD-positive patients receiving myeloablative (n = 155) or non-myeloablative HSCT (n = 86). MRD was assessed in bone marrow aspirated obtained prior to transplant.10

Another example is provided by a persistently positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for NPM1, despite the overall better prognosis indicated by the mutation per se. In a recently reported study, quantitative real-time PCR analysis of NPM1 mutations (sensitivity of 10−6) was investigated in 158 patients enrolled in the prospective clinical trials AMLCG 1999, 2004, and 2008. The authors had 588 samples obtained in aplasia, after induction and therapy, and during follow-up. Patients with NPM1 mutation ratio of 0.01 following induction therapy had a hazard ratio of 4.26 for AML relapse, and the 2 year cumulative incidence of recurrence was 77.8% versus 26.4% for patients above and below the 0.01 mutation ratio.13

Several covariates should continue to be taken into account when incorporating genetic information to improve our ability to predict AML resistance.14,15 An example is provided by the interaction of NPM1 and age. The “protective” effect of NPM1 gene mutation does not appear to extend to patients older than 65 years, as demonstrated by a retrospective analysis of AML patients aged 55 years or older treated in trials of the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) and UK National Cancer Research Institute/Medical Research Council. Whereas the 2 year overall survival of NPM1–positive/FLT3–ITD-negative AML patients 55-65 years old was better than patients without this genotype (70% vs 32%; P < 0.001), this protective effect was not seen among patients older than 65 years, (27% vs 16%; P = 0.33).16

Although most investigators would not recommend allogeneic HSCT in first complete remission (CR) for intermediate-risk cytogenetics, NPM1–positive/FLT3–ITD-negative AML patients, another recently published retrospective study reviewed outcomes of such patients after allogeneic HSCT in a donor versus no donor fashion. NPM1–positive patients with intermediate-risk karyotype (n = 304) treated on the Study Alliance Leukemia AML 2003 trial (n = 1179, age 18-60 years) were reviewed. In that prospective clinical trial, patients in CR were to receive an allogeneic HSCT if an HLA-identical sibling donor was identified, whereas those without a sibling donor were to receive autologous HSCT or chemotherapy consolidation. Among NPM1–positive patients, 77 had a sibling donor, and 227 did not have a family donor. Relapse-free survival was 71% and 47% (p = 0.005), in the donor versus no-donor cohorts, respectively. Overall survival was not statistically different (70% vs 60%, respectively), likely due to good response and survival for NPM1 patients after relapse and salvage therapy in the no-donor cohort.17

New classification systems incorporating “classic” and newer prognostic covariates have been developed to refine risk assessment of the patient with AML in first CR.18,19 The European LeukemiaNet has proposed a consensus recommendation that takes into account AML intrinsic risk, the risk of relapse after consolidation, and prognostic scores for predicting nonrelapse mortality. AML risk is stratified as good risk [includes patients with t(8;21) with WBC ≤20 K/mm3, Inv(16)/t,(16,16) double-allelic mutated CEBPA, mutated NPM1 (without FLT3–ITD mutation), and with early first CR without MRD], intermediate risk [t(8;21) with WBC >20 K/mm3, diploid cytogentics (or with loss of X and Y chromosomes), WBC count ≤100 and early first CR achieved after one induction chemotherapy], poor risk (good or intermediate risk without CR after first cycle of induction chemotherapy, diploid cytogenetics with WBC >100 K/mm3, or with cytogenetics abnormalities), and very poor risk (patients with monosomal karyotype, abnormality 3q26, or with enhanced ecotropic viral integration site 1).

The decision to refer a patient to HSCT, however, has to take into account disease-specific covariates, but cannot ignore patient-related variables such as age and comorbid conditions, and the intrinsic risk of the procedure. By incorporating matched unrelated, haploidentical, and cord blood donors, most AML patients will, in theory, have access to allogeneic HSCT. Our time-honored strategy of determining the role of allogeneic HSCT by genetic randomization (donor vs no-donor) used to consider only well matched related, or more recently, unrelated donors. It is unclear how the broader donor availability will affect long-term outcomes, but the studies described in Table 1 will soon have to be complemented by comparisons of haploidentical versus unrelated donors, for example.

Donors for everybody

Another important development in transplantation, although not AML-specific, is the rapid expansion of the donor pool due to the increasing number of available unrelated donors, unrelated cord blood units, and more recently, widespread use of haploidentical donors. A detailed review of the pros and cons of each donor source is beyond the scope of this article, but can be found elsewhere.20-22 Speed of procurement and donor availability are strong considerations when treating AML, and “alternative donor” transplants are under active investigation worldwide. A matched related donor remains the preferred therapy, but most patients do not have matched siblings. Interestingly, single-center and registry analyzers indicate similarity in outcomes of matched related or unrelated transplants for AML, and also after unrelated cord blood.23 Emerging single-center data would extend this similarity of outcomes to haploidentical transplants. Therefore, donor choice may become a matter of center expertise, speed of procurement, availability of cells for post-HSCT therapy, and disease tempo. Interpretation of retrospective data is limited, however, by the interplay of several covariates such conditioning intensity, recipient age, disease status and risk at HSCT, amongst others, as discussed in the sections above.24

It is also possible that donors can be chosen based on their ability to exert the graft-versus leukemia (GVL) effect. AML is very amenable to natural killer (NK) cell reactivity, and at least one specific activating killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) has been shown to lead to improved AML outcomes after unrelated donor HSCT. The authors formulated the central hypothesis that donor-derived 2DS1, an activating KIR with specificity for HLA-C2 antigens, activates NK cells, leading to less relapses. Donors with KIR 2DS1 were associated with lower AML relapse rates amongst a large cohort of donor-recipient transplant pairs reported to the National Marrow Donor Program (26.5% vs 32.5%; hazard ratio, 0.76). This hypothesis is now under prospective investigation.25

Peri transplant

Reduction in early mortality

A notable trend in allogeneic HSCT has been a significant reduction in early transplant-related mortality (TRM). The reasons for this are several, and include a general improvement in supportive care, in addition to transplant-specific changes. The last 2 decades witnessed a fast rise in the median age of HSCT recipients, closer to the peak age incidence of several hematologic malignancies. Although outcomes of HSCT for AML have to be analyzed keeping in perspective the intrinsic patient selection process, a larger minority of AML patients are potentially eligible for allogeneic transplantation. As an example, since the year 2010, 34% of all newly diagnosed AML patients went on to receive an allogeneic HSCT in our institution. In Seattle, of 212 new AML patients, 67% of those in CR1 (n = 78) received a HSCT in CR1 (32% of all patients).1 Transplant-specific reasons for this trend include transplant center expertise, use of less-toxic conditioning regimens, quality initiatives with standardization of procedures and practices, and improved physiologic pre-HSCT risk assessment of TRM.26-29 As mentioned above, the trade-off of decreasing early mortality and treating older patients with less intense preparative regimens has been an increase in relapse rates, and relapse prevention is a major unmet need in the field.

Decreasing the toxicity of the preparative regimen

Although the choice of conditioning regimen is frequently an institutional one, the most commonly used regimens for transplanting AML are now intravenous busulfan-based. In the absence of prospective, controlled phase III studies, large registry data analyses indicated improved outcomes with this agent given IV.30,31 It is also largely assumed that both oral and IV busulfan administration is made safer by careful pharmacokinetic (PK) monitoring and guided dosing. Reproducibility and a more predictable pharmacologic profile have led to our ability to attain dose intensity with this agent in a significant proportion of AML patients up to the 6th to 7th decades of life. Unfortunately, relapse rates remain stubbornly in the range of 20%-50%. The “dose-intensity conundrum” rules: higher intensity is associated with less relapses and more TRM, although the reverse holds true with less intensity.32,33 This inverse relationship provides a major rationale for post-transplant interventions to prevent AML recurrence, as discussed below, and also for the investigation of new agents in the preparative regimen.

Incorporation of treosulfan (L-threitol-1,4-bis-methanesulfonate; dihydroxybusulfan) to chemotherapy-based preparative regimens has led to remarkably low toxicity rates, especially in the pediatric field. This drug is under active investigation in the United States and Europe.34 Clofarabine has been proposed as a replacement for fludarabine in combination to busulfan, with the rationale that this drug retains immunosuppressive effects with added direct anti-AML effects, as opposed to fludarabine, which is not an effective anti-AML agent per se.35

Future approaches may include the incorporation of monoclonal antibodies to the conditioning regimen “frame”. It is expected that newer antibodies will have non-overlap toxicities with classic drugs, such as antibodies targeting the myeloid antigen CD33.36,37 This would enable investigators to ideally increase dose intensity without increasing TRM. Radioimmunoconjugates are discussed in Dr Walter's presentation.38

Targeted marrow irradiation (TMI) was initially proposed by the City of Hope Hospital group, and is under investigation in several institutions in the US. The technique takes advance of modern radiotherapy technology that allows mapping of the skeleton and marrow space, minimizing collateral tissue damage, and allowing significant radiation dose escalation. Radiation doses of up to 16 Gy have been administered without concomitant chemotherapy, whereas 12 Gy was safely added to the fludarabine/melphalan reduced intensity-conditioning regimen. The authors also observed that TMI dose could be escalated to 15 Gy when combined to etoposide and cyclophosphamide, but not to busulfan for 4 days and etoposide, due to mucositis and hepatic toxicity.39,40 Our group is currently investigating whether TMI added to the reduced intensity busulfan (2 days) and fludarabine regimen will decrease relapse rates. Table 2 summarizes ongoing, prospective preparative regimen studies for AML as reported on www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

Graft engineering and cell therapy

A comprehensive review of graft modification studies is beyond the overall goal of this review, but can be found elsewhere.41-43 However, as listed and summarized in Table 3, there are several national and international groups investigating the use of antigen-specific and antigen-nonspecific cellular approaches to treat AML (also reviewed in Dr Walter's presentation38 ). Conceptually, ex vivo expanded and/or engineered cells can be added to the graft itself, or be used afterward to treat MRD, prevent recurrence, or to treat overt relapse.

Arguably, adoptive cell therapy using NK cells has the longest track record of investigation to treat AML, second only to donor lymphocyte infusions (DLI). AML remissions have been documented using adoptive transfer of haploidentical NK cells. The major limitations have been NK cell survival and expansion after transfusion, and our ability to obtain large numbers of cells. Several groups are investigating ways to overcome these limitations. Innovative approaches have included host regulatory T lymphocyte depletion to minimize NK cell rejection, ex vivo expansion of NK cell numbers by using artificial antigen-presenting cells, use of interleukin (IL)-15 instead of IL-2, and development of NK cell chimeric antigen receptors.44 Lymphodepletion and IL-2 usage have become standard approaches in the NK cell therapy field, but IL-2 use is also associated with in vivo Tregs expansion (whereas IL-15 is not), which in turn may lead to NK cell rejection and inhibition. The University of Minnesota group treated 57 AML patients with cyclophosphamide and fludarabine followed by NK cell infusion and systemic IL-2. The authors also treated a subset of 15 patients with the IL-2-diphtheria fusion protein to deplete host lymphocytes. Interestingly, NK cell expansion occurred in 27% of the 15 patients, whereas only 10% of the remaining patients had evidence of NK cell peripheral blood expansion. In addition, CR rate was higher with the fusion protein (53% vs 21%), and 6 month disease-free survival was improved (33% vs 5%).45,46

Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) is a protein kinase that mediates the addition of phosphate molecules onto serine and threonine. GSK3 inhibition increases adhesion of NK cells to target cells. In addition, it increases expression of NK cell-target adhesion molecules, such as L-selectin on NK cells and ICAM on target cells, and increases granzyme and perforin expression and secretion of IFNgamma by NK cells.47 It is therefore possible that NK cell activity can be increased by pharmacologic means using GSK3 inhibitors. Our group is investigating if NK cell incubation with a GSK3 inhibitor prior to adoptive transfer will improve anti-AML activity of infused cells.

Another promising approach to prevent relapse or treat AML is adoptive immunotherapy using ex vivo expanded T lymphocytes. Antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes capable of recognizing tumor-associated AML antigens are frequently found in healthy individuals, and could be used to treat AML without matching limitations.48 Wilms tumor-1 (WT-1) cytotoxic T lymphocytes are under investigation by several groups (Table 3). Tumor-specific associated antigens, such as WT1, PRAME, SURVIVIN, and MAGE are potential targets. Antigen-specific lymphocytes may be generated from recipients or their donors, under the hypothesis that multiple targeting may prevent tumor immune evasion.41 Future directions may also include the use of CD123-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) transduced lymphocytes, as proposed by the City of Hope group.

Post-transplant

Pharmacologic maintenance of remission therapy after HSCT

Outcomes of AML relapsing after allogeneic HSCT are poor, especially for patients relapsing early. Long-term survival is in the range of 5%-30%, and long-term survival seems to occur only when salvage therapy includes a second HSCT or DLI.49,50 The median time to relapse is to some extent related to the intensity of the preparative regimen and to disease status at HSCT, but most relapses occur within the first year, with a peak incidence during the first 3-6 months. Therefore, interventions to prevent recurrence have to be implemented early, when graft function is vulnerable to myelosuppression and immune recovery may be jeopardized by the proposed treatment. In addition, drug interactions have to be taken into account, especially in the first months after transplant, as exemplified by ganciclovir for CMV infection, which can potentiate myelosuppression of several medications.

The ideal maintenance agent should have some desirable characteristics. It should be tolerable in the context of multiple drug use, be active against AML, should not be myelotoxic (or with tolerable myelotoxicity), and therefore be easy to administer early after transplant. In addition, it should influence donor cells favorably (does not promote GVHD, and does not inhibit the graft-versus-leukemia effect), and ideally, increase immunogenicity of malignant cells.

Considering the potential risks of post-HSCT treatments,51 2 general approaches have been investigated. One is based on relapse risk determination made prior to HSCT, with intention to start maintenance therapy in a predetermined time frame, whereas another approach is triggered by presence or reappearance of a MRD marker, such as flow cytometry showing clonal myeloblast populations in the marrow or peripheral blood. The former may potentially expose more patients that are already cured to an unnecessary treatment, whereas the latter, although more “selective” an approach, assumes that current MRD measurements are efficacious, widely available and done frequently, before evidence of hematologic relapse is found. It is largely unclear if one strategy is superior. Dosing drugs in the context of early post-HSCT scenario is complex and should only be proposed in prospective studies. In addition, proving activity of the treatment is not a trivial pursuit, and ultimately randomization will have to be performed.3,4

We have had limited success in separating GVHD from the GVL effect. Post-HSCT research has focused mostly at preventing GVHD while attempting to preserve the anti-cancer activity. Recently, availability of new small molecules and monoclonal antibodies is providing investigators with a larger repertoire of options to prevent AML recurrence post-transplant. This is an important endeavor, given that, as a matter of fact, there is a trend toward higher relapse rates than in the past, a likely result of increased early survival rates, and of the use of allogeneic HSCT to treat older patients.

The only drug currently undergoing phase III, randomized maintenance evaluation is the DNA methyl transferase inhibitor azacitidine. We originally hypothesized that low doses of this agent would decrease relapse rates after HSCT based on previous knowledge generated in the 1980s and early 1990s demonstrating higher tumor antigen and HLA molecules expression in leukemia cells in vitro after exposure to hypomethylating agents. We then observed that low doses of the drug (16-40 mg/m2 for 5 days) were capable of inducing remission in a minority of AML patients relapsing after allogeneic HSCT. The dose of 32 mg/m2 daily for 5 days was well tolerated in a phase I maintenance study which also suggested that chronic GVHD incidence was decreased, raising the intriguing hypothesis that hypomethylating agents may modulate GVL and GVHD.52 Subsequent murine experiments performed by others showed that decitabine or azacitidine could induce immunologic tolerance, possibly by increasing the numbers of Tregs lymphocytes.53,54 Interestingly, a multicenter British study that investigated low-dose azacitidine after T-cell depleted HSCT also found an increase in tumor antigen CD8+ T-cell responses, in parallel with increased reconstitution of Tregs.55 The feasibility of low dose azacitidine maintenance was illustrated by the CALGB 100801 (Alliance) study, which aimed at determining the feasibility of pharmacokinetic adjustment of busulfan in the preparative regimen, and of administering up to 6 cycles of low-dose azacitidine 32 mg/m2 daily for 5 days, in 28 day cycles after HSCT. This multicenter study confirmed that a majority of patients are able to receive azacitidine (66%).56 A phase III study comparing 1 year of low-dose azacitidine maintenance versus standard of care (ie, no maintenance) is ongoing at MD Anderson Cancer Center. The study investigates if azacitidine will improve EFS of AML or high-risk MDS patients receiving T-cell replete allogeneic HSCT.

Given the paucity of randomized studies, several questions remain. One question relates to the issue of sustainability of the effect. Is the intermittent administration of a drug enough to induce a sustained effect on donor cells, and to eradicate leukemia stem cells? Preclinical models would indicate that epigenetic effects do not persist after pharmacologic intervention is stopped, for example. If one effect of low dose azacitidine is to induce tolerance and, inhibitory, regulatory T cells, could we actually increase the risk of relapse? Although preliminarily this does not seem to be the case, it reinforces the need for controlled, randomized studies given the multiple confounding effects involved here. Another unanswered question is duration of maintenance therapy. Logistics, patient tolerance, and “treatment fatigue” are major issues here, which can decisively affect compliance and our ability to monitor treatment. We have arbitrarily proposed 1-2 year duration, under the rationale that most relapses tend to occur during that time frame, but trials have been designed in even shorter time frames solely due to logistic reasons.

In view of the preliminary positive outcomes using low dose parenteral azacitidine, a Phase I maintenance study utilizing the oral epigenetic modifier drug CC-486 is ongoing in AML and MDS patients post-allogeneic HSCT. It is possible that prolonged “metronomic” exposure to lower doses of the agent may improve outcomes. In addition, oral administration may improve compliance. The AUC range for oral CC-486 is ∼10% of that seen with subcutaneous azacitidine administered at 75 mg/m2. Administration for 7 days of each 28 days is safe and relatively well tolerated, and 14 day administration schedules are currently being investigated.57

FLT-3 tyrosine kinase inhibitors are also under active investigation as maintenance therapy after HSCT (Table 4). The central hypothesis borrows from the non-HSCT treatment of FLT-3–positive AML. Patients bearing the ITD mutation have a higher likelihood of relapse, and it is possible that maintenance therapy with FLT-3 inhibitors will reduce recurrence rates. One such agent is quizartinib (AC220), an oral FLT3 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. A multicenter phase I study examined quizartinib maintenance therapy in FLT3+ AML patients in CR after allogeneic HSCT. Two dose levels were tested: 40 mg (n = 7) and 60 mg (n = 6) given daily in 28 day cycles. Thirteen patients with a median age of 43 years were treated. Toxicities were manageable, and 77% of the patients received quizartinib for >1 year. Only 1 patient relapsed, suggesting a lower than expected relapse rate. Although the study did not investigate higher doses, 60 mg daily is the recommended dose given also emerging data outside the HSCT realm.58 A phase I study led by the Massachusetts General Hospital team investigated the oral inhibitor tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib. FLT3+ AML patients (n = 22) received the drug after myeloablative (n = 12) or reduced intensity (n=10) HSCT. Donors were matched related (n = 18), unrelated (n = 2), haploidentical (n = 1), or double-umbilical cord blood (n = 1). The drug was started between HSCT days 45 and 120, and administered continuously for twelve 28-day cycles. Disease status at HSCT was first CR (n = 16), second CR (n = 3), or refractory (n = 3). The maximum tolerated dose was 400 mg twice daily. Common toxicities included skin rash and gastrointestinal symptoms. There were no indications of effects on GVHD rates (incidence of chronic GVHD was 42%). After a median follow-up of 14.5 months, 1 year progression-free and overall survival was 84% and 95%. These very promising results clearly deserve further evaluation, hopefully in a randomized controlled fashion.59

Investigators in Germany are studying the deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat to prevent recurrence of AML or MDS after HSCT, hoping to take advantage of panobinostat's immunomodulatory effects, as well as the inhibitory effect of histone deacetylase inhibitors on survival and proliferation pathways of leukemic stem and progenitor cells. The reported maximum tolerated dose is 20 mg in 3 weekly doses, with treatment started at day 60 after HSCT. The dose-limiting toxicity was colitis and nausea at the 30 mg dose.60

The small molecule hedgehog inhibitor PF-04449913 is also under investigation as maintenance of remission agent. It appears that survival of leukemia stem cells is favored by abnormal hedgehog signaling, and the hypothesis that inhibition of this pathway may decrease relapse rates after allogeneic HSCT is being tested in an ongoing US phase II study (Table 4).

The possibility that newer pharmacologic interventions could have an additive effect with cellular treatments post-HCT is fascinating and opens a wide array of investigations, as discussed in previous sections of this review. Conceivably, antigen-specific or nonspecific cellular maintenance strategies could be magnified by concomitant administration of drugs that might enhance the effects of cellular therapy. Several groups are currently investigating this possibility.

Conclusions

The post-transplant milieu, once the realm of GVHD studies, may provide an ideal arena to improve disease control now that newer therapies (cellular and otherwise) are available. We are likely to see the distinction between HSCT and non-transplant treatments' fade, as we enter an era of combined cellular and pharmacologic therapies for AML and other diseases.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the following colleagues for their input: Jean Khoury, Steven Devine, Sergio Giralt, and Richard Champlin.

Correspondence

Marcos de Lima, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, 11100 Euclid Ave, LKS 5079, Cleveland, OH 44106; Phone: 216-983-3276; Fax: 216-201-5451; e-mail: marcos.delima@uhhospitals.org.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has consulted for Celgene and Seattle Genetics.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: Most drugs used in transplantation do not carry a label for that indication.