Abstract

A 45-year-old woman with a history of uterine fibroids and abnormal uterine bleeding presents to the emergency department (ED) with presyncope and weakness. A gynecology consultation for definitive management was requested. The complete blood count demonstrates a hemoglobin (Hb) of 6.5 g/dL and a mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of 65 fL. What is the role of IV iron in managing iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) presenting to the ED/urgent care?

Learning Objectives

Identify the impact of IV iron on red blood cell utilization, health care utilization, and patient outcomes in managing iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) presenting to the emergency department (ED)

Manage a hemodynamically stable patient with IDA presenting to the ED

Discussion

IDA is estimated to affect over 1 billion children and adults worldwide,1 making iron deficiency the largest contributor to the global anemia burden.2 IDA disproportionately affects children and women of childbearing age regardless of socioeconomic status or geographic boundaries. IDA negatively impacts physical, functional, cognitive, and emotional health.3,4 The number of ED visits resulting from IDA is unknown, and there are no formal guidelines to direct management. In a retrospective chart review of ED visits to a large tertiary care hospital, 49 patients were identified as having IDA by the ED physician over a 3-month period.5 Of patients with an identified cause for their IDA, gynecologic followed by gastrointestinal (GI) sources of blood loss were most common. Nineteen of 49 patients were transfused with red blood cells (RBCs); only 53% of the transfusions were deemed appropriate for both indications and number of units, suggesting RBC transfusion is overutilized in management of IDA in the ED. IDA in women and girls with gynecologic bleeding results in significant adverse symptoms and health care utilization. In a study of 107 adolescent girls with heavy menstrual bleeding and IDA, more than half initially sought urgent attention for their symptoms, with 72 patients (67%) presenting to the ED with a mean Hb of 7.4 g/dL; 50% of these patients required hospital admission.6

Optimal oral iron therapy7 and the availability of newer, safer, effective, and well-tolerated IV iron formulations8 have contributed significant advances to the treatment of IDA in adults. Although fewer formulations have approval for use in pediatric populations, a recent large retrospective study of over 1000 IV iron doses in children found no serious reactions.9 Yet, a study in children found that one-third of patients presenting with pediatric IDA in the ED received RBC transfusion.10 Every unit of transfused RBCs carries potential infectious, immune, inflammatory, and volume-related risks.11 The American Association of Blood Banks’ Choosing Wisely campaign recommends against RBC transfusion in the hemodynamically stable patient with IDA.12 For IDA in the ED, the use of IV iron to rapidly replete iron and support erythropoiesis has potential to reduce exposure to RBC transfusions, reduce health care utilization, and improve patient outcomes.

Methods

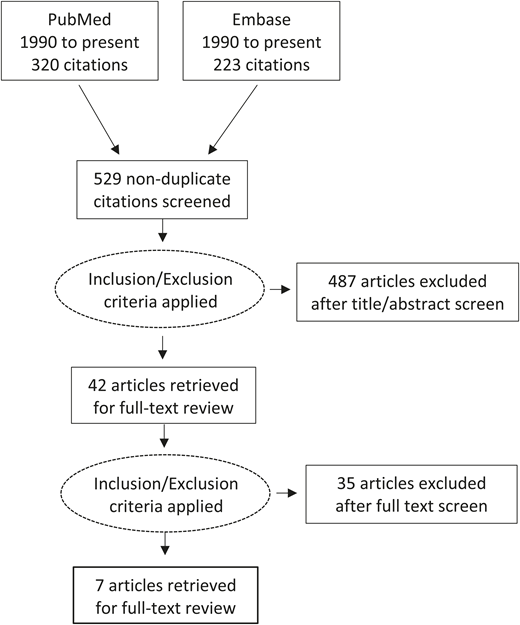

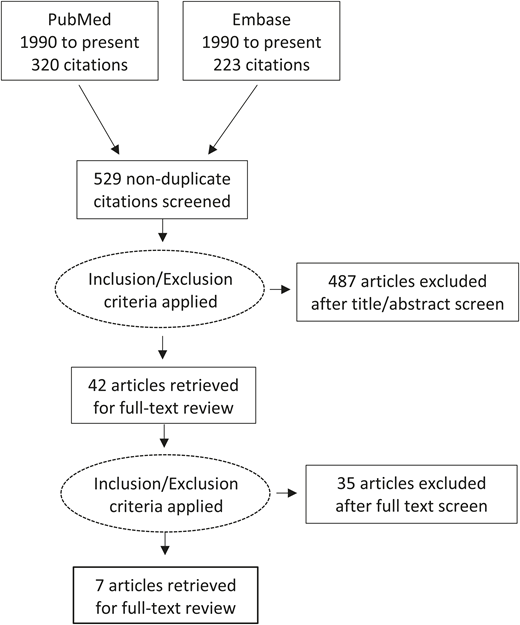

A systematic search of PubMed and Embase from 1990 to 30 May 2019 was performed. The search was limited to 1990 onward in order to focus on interventions with new, more well-tolerated IV iron formulations. The systematic search strategy for PubMed included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords. References of narrative reviews were screened. Risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale13 ; certainty of evidence was assessed according to Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE; www.gradeworkinggroup.org).

Results

Figure 1 illustrates the study selection. There were 543 articles, with 529 nonduplicate titles and abstracts returned from the 2 databases. Articles were excluded that did not include the target population, an intervention with IV iron compared with control, standard of care, or placebo, or the target outcomes of RBC transfusion, health care utilization, or other patient-important outcome. There were 522 articles excluded at completion of initial screen and full text review: 345 were not studies of patients with IDA in the ED or urgent care setting, 107 did not include an intervention with IV iron, 6 did not report on the target outcomes, 12 were editorial or opinion pieces, 9 were review articles, 3 articles were not studies in humans, and 40 were case series of 10 or fewer individuals. Seven papers underwent full text review and data extraction; these included 4 pre–post studies,14-17 1 retrospective cohort study,18 1 retrospective cost study,19 and 1 quality improvement study.20

Impact of IV iron on RBC transfusion

Three papers reported on RBC transfusion outcomes after an intervention with IV iron for management of IDA in the ED. Two papers were pre–post studies and 1 was a quality improvement study; none included control cohorts. The quality improvement study20 selected achievement of >80% appropriateness of RBC transfusion as their study outcome. The study involved treatment of 211 patients following education sessions to ED physicians, according to an ED IDA management algorithm that included use of IV iron. From a historical average of 53%, the appropriateness of RBC transfusion improved to median percentage appropriateness of 91% sustained over a 2-year follow-up period. Two other studies, both published as conference abstracts, reported reduction in overall number of transfused RBC units after the implementation of their interventions, which included IV iron in addition to other measures (Table 1). One of the studies15 reported statistical testing of the absolute reduction in yearly RBCs, which they found to be significant.

Impact of IV iron on health care utilization

Two studies addressed the impact of IV iron on an outcome related to health care utilization.18,19 One, a retrospective cohort study,18 reviewed 2844 patients with GI sources of blood loss who were treated with IV iron compared with oral iron after an initial presentation for IDA. The initial visits were subcategorized into elective or emergency initial presentation. The primary outcome was reattendance to either elective or ED within 30 days of initial presentation. In the subgroup of patients presenting to the ED with IDA, 64 received IV iron and 1037 received oral iron. The authors report that patients treated with oral iron during their initial ED visit were more likely to return to the ED (Table 2). A second study undertook a retrospective cost analysis for management of IDA diagnosed in the ED via an expedited, fast-track anemia clinic using IV iron compared with the theoretical cost of the same cohort managed in a standard care pathway (SCP).19 They evaluated fixed and variable costs related to IV iron and RBC transfusion and found a savings of 73 euros per patient with the intervention of IV iron in a fast-track clinic, an 11.6% reduction of the projected cost in SCP.

Impact of IV iron on hematologic outcomes

Two studies, both pre–post study design, reported improvement in hematologic variables related to IDA, including Hb, MCV, and iron indices over follow-up periods of 4 weeks17 and 3 months,16 after treatment with mean 1500 mg and 1144 mg, respectively. In both studies, the mean Hb, MCV, and ferritin increased after treatment with statistical significance reported (Table 3). Interestingly, in 1 study, the mean Hb posttreatment remained within anemic range (mean Hb, 11.6 g/dL) at 3-month follow up, despite a report of a statistically significant rise from pretreatment baseline.16

Limitations

Duration of follow-up and outcome reporting were variable among the studies. Additionally, the available studies are observational consisting of pre–post study designs and 2 retrospective cohort studies, yielding a body of evidence that is of overall low quality. In the studies with RBC utilization outcomes,15 hospital readmission outcomes,18 and efficacy outcomes,17 some had significant risk of bias. For each of the outcomes analyzed, our conclusion was an overall low certainty of evidence. Although the conclusions of this review are therefore limited, we can make the following observations: IV iron as part of an algorithm for IDA management in the ED improves appropriateness of RBC transfusion and decreases RBC utilization. Further robust controlled studies are needed to test these outcomes. Compared with oral iron, IV iron improves subsequent readmission rates for patients with IDA from a GI cause; generalizing these findings to patients with IDA from other causes requires further study. Compared with SCP, a dedicated fast-track anemia clinic using IV iron for treatment of IDA presenting to the ED offered lower direct costs than RBC transfusion. The use of IV iron for management of IDA presenting to the ED improved absolute Hb, MCV, and iron indices.

This review did not address the importance of identifying and managing the underlying etiology of IDA. Iron repletion is only 1 part of managing IDA; thorough investigation through clinical history, physical and laboratory findings, and diagnostic imaging is often required to identify the cause of iron deficiency. Once the cause is identified, appropriate treatment options must be offered/pursued where applicable.

Conclusion

In summary, strong recommendations cannot be generated based on limited observational studies, lack of controls, variable outcomes, risk of bias, and low certainty of evidence. However, in considering the prevalence and severity of IDA, significant sequelae of anemia, risks inherent in RBC transfusion, safety and efficacy of IV iron, resources and cost of both RBC transfusion and IV iron, acceptability to stakeholders, and feasibility of the proposed intervention, we have generated the following conditional recommendations.

Conditional recommendations

In the hemodynamically stable patient with IDA presenting to the ED, we suggest considering the use of IV iron over RBC transfusion.

In the hemodynamically stable patient with IDA presenting to the ED, we suggest considering the use of IV iron over oral iron.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Bram Rochwerg for guidance on GRADE methodology.

Correspondence

Michelle P. Zeller, McMaster University, 1200 Main St W, HSC 3H54, Hamilton, ON L8N 3Z5, Canada; e-mail: zeller@mcmaster.ca.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.P.Z. has participated in Pfizer advisory boards and received research funding from Canadian Blood Services (CBS). McMaster Centre for Transfusion Research receives partial infrastructure funding from CBS and Health Canada. J.G.R. declares no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.