Abstract

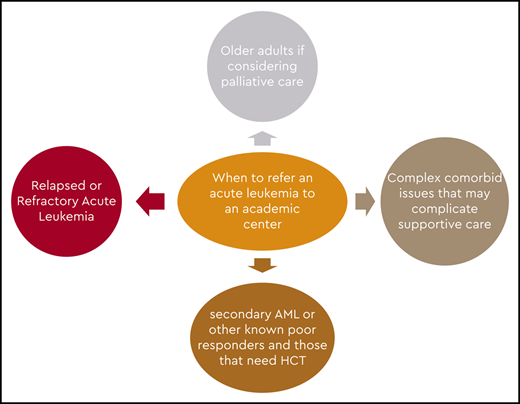

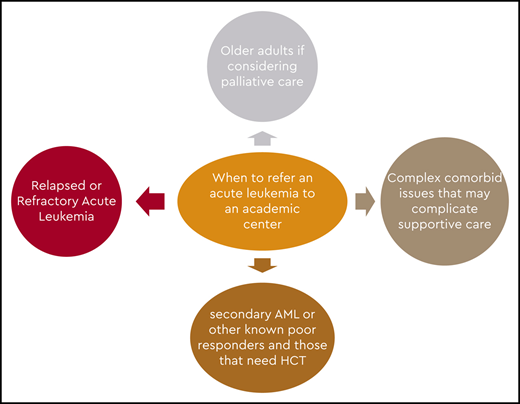

Treatment of acute leukemia has been delivered predominantly in academic and larger leukemia treatment centers with the infrastructure and staff needed to manage patients receiving complex therapeutic regimens and supportive care. However, in recent years, several oral agents and less-myelosuppressive regimens were approved, making it possible for these patients to receive therapy in smaller community hospitals and oncology office practices. In this review, we discuss the optimum community setting, type of patient who can be treated, agents that can be applied, and an appropriate clinical circumstance in which a referral to a tertiary center should be made.

Learning Objectives

Manage acute leukemia in the community setting

Understand the barriers to treatment of leukemia outside of academic centers

Introduction

The incidence of leukemia in adults in the United States is 6.9 per 100 000 per year (from 1973 through 2014), and the lifetime risk of developing leukemia is 1.5%.1 Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is the most common type of acute leukemia in adults and accounts for 80% of all leukemias.2 The goal in younger patients with no comorbid conditions is a curative approach using intensive chemotherapy with or without targeted agents. This approach might be followed by bone marrow transplant on the basis of risk stratification and donor availability. For older patients and young patients with comorbid conditions, the use of curative intensive therapy is precluded, and the expectations are palliative, with an approach intended to prolong and maintain a reasonable quality of life.

For decades, the available agents for intensive induction have been “7 + 3” (anthracycline and infusional cytarabine).3 This treatment was most frequently within the purview of academic teaching hospitals and larger community hospitals with programs to treat patients with acute leukemia. Alternatively, if the patient was incapable of tolerating intensive chemotherapy, other available options were hydroxyurea or low-dose cytarabine (LDAC).4

In the last 10 years, several new agents have been approved for AML, for both oral and parenteral use, offering additional options for older patients and making therapy of AML feasible in the community setting for most patients. Some of the newer agents are hypomethylating agents (HMAs), targeted agents such as FLT3 inhibitors, isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) inhibitors, hedgehog inhibitors, gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO), and venetoclax.5-13 Smaller community health care facilities and office-based private practices are increasingly treating patients with AML with some of the recently approved novel agents.

Because this is a recent paradigm, there is inadequate published literature on treating acute leukemia in the community. Hence, several of the topics discussed in this article and the recommendations suggested are derived from our own experience in developing and supporting a hematologic malignancy network in our catchment area (Table 1).

Our experience in engaging our community

For almost 25 years, our team has worked at developing a network of community hospitals and office-based practices in a catchment area comprising a population of 3.5 million. The catchment area is a patient referral base for the Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University (Augusta, GA). Subsequently, we used this network to implement a clinical trial in the management of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). The cure rate and long-term survival for APL in clinical trials is >90%, although this is not true in the general population.14-17 The induction mortality or early deaths (EDs) in APL is ∼30%, and the long-term survival of all patients with this diagnosis is in the 65% range.18-20 We conducted a study by developing a network of leukemia treatment centers in Georgia, South Carolina, and neighboring states. The study design provided a simplified 2-page treatment algorithm that emphasized quick diagnosis, prompt initiation of therapy, and proactive and aggressive management of the major causes of death during induction. APL expert support was available 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, to the treating physician very early in the diagnosis and was maintained until the completion of induction. As a result, patients were treated in local community hospitals by local oncologists rather than being transferred to a tertiary center. An aggressive outreach effort was made before initiating the trial by visiting most of the leukemia treatment centers to make our community partners aware of the availability of this program and educate treating physicians about ED in APL. A total of 120 patients were enrolled with no exclusion criteria at 5 large leukemia centers (n = 54 [45%]) and 18 community hospitals (n = 66). There were 12 EDs, one of which was in a Jehovah’s Witness who declined transfusions and one in a patient who enrolled 12 days after diagnosis while already in multiorgan failure. The incidence of EDs was 10 (8.5%) of 118. With a median follow-up of 320 days, overall survival was 87%. This prospective trial showed that a simplified treatment algorithm along with support from experts and comanagement with treating physicians in the community decreased induction mortality and improved survival.21 Although there was no control arm in this study and historical data were used for comparison, it is our impression that the process used and the academic–community partnership resulted in an improved outcome. This pilot study subsequently paved the way for activation of the ECOG-ACRIN 9131 trial to decrease induction mortality in APL using the same methodology. The trial is currently accruing patients nationally. Our experience and study demonstrate the possibility of improved outcomes with academic–community partnerships.

From the above study and experience, we learned the following to enhance community–academic partnership and collaboration:

Initially, the community physicians did not think EDs were a problem in APL, but with time, support for the trial became stronger.

It helps for referring physicians to have direct and easy access to academic physicians, such as through direct office and cell phone numbers.

Physically visiting the community practices and developing a relationship with the physicians and staff are very effective.

Participating in state and regional meetings attended by community physicians results in strengthening the collaboration.

Meticulous communication and articulating the postdischarge plans in a written note and transmitting them to the referral practice create dependability.

Hospital diversion and nonavailability of beds at the academic center can be a frustrating problem for community oncologists.

Having the necessary support staff in an academic center to carry out the above functions is important.

General treatment of leukemias

Treatment centers

Before we proceed to how we manage patients in a community setting, it would be worthwhile to define what constitutes a community leukemia-treating center. Some data are available on where leukemia patients are treated in the United States. The majority of patients are treated in university teaching hospitals and larger leukemia-treating community hospitals. In a study by Zeidan et al22 of 6442 patients with AML treated with induction chemotherapy, 95.6% of patients were treated in urban areas, 59.5% in teaching hospitals, and 55.5% in large hospitals with >500 beds. For instance, in the state of Georgia, with a population of 10.5 million, there are 134 hospitals, 20 of which treat patients with acute leukemia. Two of the 20 hospitals are university teaching hospitals, and the others are large community hospitals.23 The large hospitals are of varying complexity, with one of them being a referral hospital that has a large leukemia service as well as a Foundation for the Accreditation of Cellular Therapy–accredited hematopoietic cell therapy (HCT) program. This might be true in other states as well. Some of the newer, less intense drugs can be administered in smaller community non–leukemia-treating hospitals as well as in private offices. As such, in general, there are 3 types of health care institutions that could provide care to patients with acute leukemia: (1) university teaching hospitals, (2) larger community hospitals, and (3) smaller community hospitals and private offices.

Do community centers want to treat patients with AML?

Obviously, community hospitals, private practices, and physicians would like to provide the whole spectrum of cancer care and keep their patients in the community. Leukemias account for <3% of all cancers, and treating them requires familiarity with treating the disease and inpatient units with trained and dedicated nursing staff and oncology pharmacists. Blood bank support and availability of blood products are key to successful management. Treating these complicated patients adds a certain level of complexity to the hospital and practice site. The physicians may want to continue treating hematologic malignancies in order to maintain their leukemia treatment skills. An AML-specific quality-of-life questionnaire administered to 82 patients undergoing active treatment revealed that family support, friends, and community were the most important patient support systems.24 As such, the added advantage is preventing inconvenience and travel hardship for patients and their families and thus would be attractive to both parties. Another reason for providing care to this patient population is a financial incentive and would be to the advantage of the smaller hospitals, private practices, and providers.

Workup

Guidelines for workup of patients with AML are available, and a comprehensive evaluation should be performed at diagnosis to make the best treatment decisions.25,26 In our setting, if leukemia is a strong consideration, we suggest that the referring physician not perform the bone marrow biopsy but transfer the patient so that the procedure can be carried out in an academic hospital. This would also give the academic center an opportunity to conduct a comprehensive evaluation to help guide therapy and eliminate undue discomfort in the patient and duplication of the testing. Also, it offers the opportunity to screen and enroll the patient in a clinical trial if available or appropriate.

Fit and unfit patients

The treatment of AML is obviously going to be different in young, fit patients with no comorbid conditions. Similarly, older patients (aged >60 to 65 years) who are fit with no comorbid conditions may be treated like the previous group, aiming for cure and considered for stem cell transplant if applicable. Younger patients with severe comorbid conditions who are deemed unfit and older patients who are perceived to be ineligible for intensive treatment will be treated in a more palliative mode. Such patients can be treated in the community setting to allow patients to be closer to home and loved ones.

Treatment of AML in young and older fit patients

Treatment of young and older fit patients depends, for the most part, on the patient’s goals and where the diagnosis is made. If the patient is diagnosed at an academic teaching hospital, management will be provided most likely at the diagnosing center. This would include the whole array of services, such as state-of-the-art diagnosis, induction, subsequent therapies as appropriate, and possibly enrollment in a clinical trial.

If patients are treated in community leukemia-treating centers, the programs are very capable of giving induction and consolidation, and some may also have access to cooperative group and industry-sponsored trials. But these centers, for the most part, do not treat many patients in any given year and generally seek advice in managing them. The centers tend to contact an academic center before initiating therapy to discuss what might be the ideal induction and consolidation regimens, as well as to seek advice should the patient have residual disease on a day 14 bone marrow biopsy or at the time of count recovery. In addition, they tend to refer patients to an academic center for evaluation for HCT, most probably at the end of leukemia induction, and for clinical trials in the event of failure of conventional treatment.

If the patient is diagnosed in a non–leukemia-treating center or private practice office, more likely than not the patient will be referred to an academic center. Given the distance and the constraints it places, these patients will receive their induction and consolidation most likely in the academic center. Due to the inconvenience distance causes to the patient and the family, we administer the consolidation at our facility but have the recovery laboratory tests, blood transfusions, and supportive care done at the local facility. There is a practical disadvantage to this approach should the patient develop a complication such as neutropenic fever or sepsis during the recovery time. The smaller hospitals may not have the infrastructure needed to manage complications, and the time it takes to get these patients to a larger center could be deleterious and compromise patient outcome. However, there is published data that supports this approach and reduces the burden of patient travel without compromising outcome.27

In the case of resistant disease, one option would be to coordinate with the non–leukemia-treating facility for the administration of an HMA along with targeted oral agents such as FLT3 inhibitors, IDH inhibitors, and venetoclax when appropriate.28,29 However, it would help to discuss the toxicities associated with these drugs, such as cytopenias and differentiation syndrome, and also to discuss appropriate doses.30

In essence, for a fit patient, the options are treatment at an academic center or a community leukemia treatment center. Close collaboration between an academic center and community leukemia treatment center is essential. This facilitates enrollment of patients in clinical trials and management of resistant disease effectively and efficiently, and it helps in making the transition to HCT seamlessly if that is required.

Elderly and unfit patients

On the basis of available data, acute leukemia is seen in 1.3 per 100 000 people younger than age 65 years and in 12.2 per 100 000 older than 65 years of age.31 The median age at diagnosis of AML is 66 years, and the incidence increases with age, with over half of the patients diagnosed at age 65 years or older. The prognosis in patients older than 65 is poor, with a median survival of 3 months. Further breakdown shows that the survival is slightly higher for patients aged 66 to 75 years (6 months) and is 2.5 months for patients aged 76 to 89 years. Merely 5% of patients older than 65 years of age are alive 5 years after their initial diagnosis.1,32 Given these data, only half of Americans aged >65 years with newly diagnosed AML, and only 10% to 20% aged >80 years, receive AML-specific therapy.33,34

Older patients also have comorbid conditions that make them both older and unfit, and the general perception is that they are unlikely candidates for intensive therapy. Patients with comorbid conditions tend to be taking multiple medications (polypharmacy) that can cause drug–drug interactions, poor tolerance of chemotherapy, and a negative impact on overall survival.35 However, data from the Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry showed that a certain subset of patients would benefit from intensive therapy at diagnosis. Similar results were also found in a population-based study in the United States.33,36

Because there is evidence to suggest that some of these patients may benefit from intensive treatment, it is reasonable to see patients aged <80 years at least once in an academic center to make a determination about whether such therapy would be appropriate. Applying one of the available tools for complete assessment of comorbidities, such as the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation–Comorbidity Index or a geriatric assessment tool, would be reasonable and would provide a more precise prediction of induction mortality.37,38 In addition, the academic center has the opportunity to perform a thorough pathologic evaluation to include molecular markers and next-generation sequencing before making a therapeutic decision. In patients with a lower white blood cell count, waiting for the cytogenetic and molecular results is not detrimental before initiating any form of therapy and offers valuable information that may influence treatment options and prognosis, so it should be encouraged for all patients. Those with very proliferative disease may be managed transitorily with hydroxyurea and aggressive supportive care while awaiting test results.39 In older patients with a high comorbidity index, treatment-related mortality from intensive induction would be unacceptably high. Patients with secondary leukemia and high-risk cytogenetics are less likely to respond to intensive therapy. Hence, patients with a high risk of induction mortality and patients unlikely to respond would be the most likely groups to receive treatment in a community hospital or a private practice office. Still, support from an academic center would be valuable because treatment options such as glasdegib + LDAC or venetoclax plus either HMAs or LDAC may offer a survival benefit. Because of the intricacies of these regimens, optimal management is required to optimize benefit and minimize risks. Guiding the continuation of therapy in patients with glasdegib + LDAC that may require up to 6 cycles to demonstrate its best outcome, or deciding when to interrupt therapy with venetoclax or to start the next cycle, or when to adjust the dose of venetoclax may benefit from discussion with academic colleagues with significant experience with these regimens. In general, single-agent and combination low-intensity treatments would be considered for these patients.

Extreme elderly patients >80 years of age

This group, given their advanced age and comorbid conditions, tends to do poorly, with a median survival in the 2- to 3-month range. However, a carefully selected group of octogenarians may benefit from therapy.40 Academic centers are frequently asked to render an expert second opinion, more so upon the insistence of family members, so that all the available options can be considered. These patients should be evaluated carefully, and the patient and the family should be engaged in an honest discussion regarding the prognosis, outcome, and, more important, the commitment required to undergo such therapy, as well as the real expectations with new therapies available for patients unfit for standard therapy. Patients and their families, for the most part, have not been through such circumstances previously, and this is uncharted territory. The visit could be used as an opportunity to educate the patient and family regarding the treatment, benefits, toxicity, and, more important, the need for multiple visits to the office and admissions to the hospital. Such honest engagement from an expert sets the expectations and has the potential to make it easier for the oncologist in the community.

Community options available for older unfit patients

LDAC

The Medical Research Council’s AML-14 trial compared LDAC with the best supportive care for patients with untreated AML. This study showed that patients who received LDAC had a response rate of 18% vs 1% for best supportive care, leading to improved survival.41 It should be mentioned that the group which had a response had a survival advantage. This continues to be the standard of care and could be applied to patients with minimal toxicity in the community. The possibility of self-administration may be attractive to some patients.

HMAs

Since their approval in 2004 and 2008, azacitidine and decitabine, respectively, have found increasing application in the treatment of unfit patients with AML. It is fair to say that the availability of these agents over the last 10 to 15 years has set the stage for a gradual transition of leukemia care in the community, and the recent approval of the oral combination of decitabine and cedazuridine may only strengthen this. In the AZA-AML-001 trial, older patients with AML with >30% leukemia cells in the bone marrow were randomized to receive either azacitidine or conventional care regimens. Median overall survival in the azacitidine arm was 10.4 months compared with 6.5 months in the conventional care arm. Similarly, the DACO-016 study compared the efficacy and safety of decitabine with best supportive care or LDAC in older patients ineligible for intensive chemotherapy. This study also showed an improvement in the median overall survival (7.7 months vs 5 months).5,6 This is by far the most commonly applied treatment in older unfit patients in the community. Patients with AML with certain mutations, such as DNMT3A, TE T2, and TP53, are more likely to respond to the HMAs, and pointing this out to practitioners in the community may be valuable. Importantly, the clinical benefit of HMAs may take 4 to 6 cycles to be observed.

FLT3 inhibitors

The currently approved drugs for AML are midostaurin and gilteritinib.7,8 In younger patients, the addition of midostaurin to chemotherapy improved survival compared with chemotherapy alone. The benefits of combining this agent with azacitidine and decitabine are currently being studied.42 Gilteritinib is also approved for relapsed refractory AML and is a very potent inhibitor of FLT3 internal tandem duplication and FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain. Both of these are oral agents and can be safely administered in community- and office-based practices, but careful attention to possible risks such as tumor lysis syndrome and liver toxicity, as well as adequate prophylaxis and management of infectious complications, is required. There are several other agents in this class being tested that could be available options in the future.

IDH inhibitors

Both the IDH1 and IDH2 inhibitors are now approved for treatment of AML.9,10 Enasidenib and ivosidenib are currently being studied in combination with chemotherapy and other agents in AML. The key to use of these agents is to test patients for the expression of these markers. Early recognition of differentiation syndrome is required. It is also important to understand the need for continuation of therapy to obtain the greatest benefit even for patients with only stable disease.

GO

The CD33 antibody has somewhat of a checkered history. GO is the CD33 antibody most studied. Pooled data from several studies showed that it produced a survival advantage, and it was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in the United States in 2000. However, it was withdrawn from the market in 2010 after one randomized study of GO showed that the toxicity was excessive and survival inferior compared with standard chemotherapy alone. The drug was reinstated in 2017 when subsequent control trials of GO combined with chemotherapy showed a benefit in event-free survival and overall survival.43 Gemtuzumab has been studied in combination with chemotherapy and HMAs, but administration of the drug requires close monitoring, given its tendency to cause both cytopenias and veno-occlusive disease. Practitioners in the community should be cautioned regarding its toxicity, and support should be offered in managing the appropriate doses.

Venetoclax

This BCL-2 inhibitor was found to be active in combination with other drugs in treating AML. When combined with an HMA or LDAC, high rate of responses have made them standard treatment for patients unfit for standard chemotherapy. The use of this option causes severe myelotoxicity and requires proper supportive care, including antimicrobial prophylaxis, optimal management of dosing and scheduling, and management of drug–drug interactions, with close communication with someone who has significant expertise that would be valuable if the patient is being treated in the community.44

Participation in clinical trials

This is an area where collaboration between community practices and academic centers could be of greatest benefit. Patients should be presented with options for clinical trials in most instances because the outcome with standard therapy, despite recent advances, remains poor. Studies conducted in rural and community settings have shown that accrual in clinical trials is <5%. Some of the reasons for poor accrual in the community include unavailability of trials, ineligibility, age, comorbid conditions, physician preference, distance, and financial considerations.45,46 Academic centers have the potential to fill this need and also have the potential for biobanking, which should be encouraged whenever possible. This can be done at various stages of treatment to include pretreated samples and samples obtained in remission and at the time of relapse and resistance. Biobanking offers the opportunity to study the samples and understand response and resistance mechanisms. Additional areas of trial recruitment would include upfront trials for newly diagnosed patients, trials for resistant disease, and trials during and after bone marrow transplant. These can be made possible by encouraging community oncology programs to consider joining national community oncology research programs. This allows them to enroll patients in the cooperative group trial programs.

Commitment from academic centers

In order to optimize management of AML in the community, there has to be collaboration in several areas between the community practices and academic oncologists. It would be valuable to conduct periodic symposia to update the community regarding available resources at the academic center. These would serve as a platform for the academic providers, such as physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and advanced practice providers, to meet with their counterparts in the community. Academic centers not only should function as a resource in clinical care but also should show leadership in other areas, such as nursing, when new therapies become available. Being a resource to pharmacists in the community and exchanging information as well as periodic visits will benefit both groups. Administrative collaboration to discuss topics such as coding, billing, and collection is constructive and advantageous to both entities.

For the practitioner in the community, easy access to an academic leukemia expert is of paramount importance. It is common knowledge that providers in an academic center are often called on a Friday afternoon or on long holiday weekends with questions regarding sick patients who have to be sent to a tertiary center. A core group of experts from the academic center should be available as a resource to answer questions and be of assistance. With the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and the challenges it poses, along with the widespread use of telemedicine, quick consultation could possibly become easier. A process to transfer acutely ill patients and to execute this quickly should be present. In many of the smaller hospitals, however, little can be done for the patient with acute leukemia. Hospital diversion and unavailability of beds are stressors to community oncologists and cause undue pressure from patients and family members. This requires a commitment from the academic center to provide that support and to earn the trust of the referring physicians and community doctors. It also has to be emphasized that academic leukemia practices cannot survive without the support of the community practices. This partnership is crucial and benefits both parties equally. To fulfill the academic mission of patient care, research, and education, this concept has to be appreciated and not ignored or forgotten. In the end, the patients and their families benefit from this arrangement.

Correspondence

Anand P. Jillella, Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University, 1120 15th St, CN 5335, Augusta, GA 30912; e-mail: ajillella@augusta.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.P.J. declares no conflicts of interest. J.E.C. consults with or has an advisory role with Amphivena Therapeutics, Astellas Pharma, Bio-Path Holdings Inc., BiolineRx, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pfizer,Takeda, and received research funding from Astellas Pharma (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), Immunogen (Inst), Jazz Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Merus (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Sun Pharma (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Tolero Pharmaceuticals (Inst), and Trovagene (Inst). V.K.K. has provided consultancy or in an advisory board role for Novartis and Pfizer.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.