Abstract

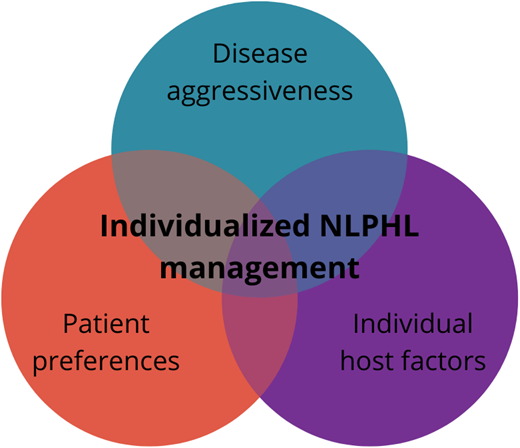

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) is a rare lymphoma that has traditionally been considered a subgroup of Hodgkin lymphoma. However, morphology, surface marker expression, genetics, and clinical course are different from classic Hodgkin lymphoma. While most patients experience indolent disease with slow progression, some patients can also have more aggressive disease. Nevertheless, outcomes are excellent, and excess mortality due to NLPHL is at most very low. The treatment of newly diagnosed NLPHL has historically mirrored that of classic Hodgkin lymphoma. However, evidence for deviations from that approach has emerged over time and is discussed herein. Less evidence is available for the optimal management of relapsed patients. So-called variant histology has recently emerged as a biological risk factor, providing at least a partial explanation for the observed heterogeneity of NLPHL. Considering variant histology together with other risk factors and careful observation of the clinical course of the disease in each patient can help to assess individual disease aggressiveness. Also important in this mostly indolent disease are the preferences of the patient and host factors, such as individual susceptibility to specific treatment side effects. Considering all this together can guide individualized treatment recommendations, which are paramount in this rare disease.

Learning Objectives

Understand treatment concepts and available evidence for the management of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL)

Understand the heterogeneity of presentation and clinical course of NLPHL

Use current concepts such as variant histology to guide patient management

Value the importance of individualized patient care in NLPHL

Introduction

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) has traditionally been viewed as a subgroup of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), accounting for about 5% of HL cases.1 However, NLPHL is distinctively different from other subgroups of HL (classic HL [cHL]), with regard to morphology and almost universal CD20 expression while lacking CD30 expression.2 Biologically, NLPHL exhibits similarities to T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma.3 Apart from typical cases, about 25% of cases have a different growth pattern, termed variant histology, associated with more aggressive disease and worse outcome.4-7

NLPHL has predominantly an indolent course.1 About 80% of patients present with early-stage disease. Peripheral lymph nodes are most often affected. Compared with cHL, B-symptoms, extranodal disease, and mediastinal disease are very rare and could suggest transformation into aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Overall, outcome is excellent, and a diagnosis of NLPHL does not increase mortality compared with the general population.8,9 Despite that, cases with a more aggressive disease course exist, and transformation into aggressive B-cell lymphoma is a clinical challenge.

In this review, I present 2 cases of NLPHL and use them to discuss treatment of clinical stage IA NLPHL, other early stages, advanced stages, and finally relapsed disease. I also briefly cover transformation into aggressive B-cell lymphoma.

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 29-year-old man (patient 1) with no relevant comorbidities presented with an enlarged left inguinal lymph node. He noticed the lymph node approximately 4 months before the initial consultation. Other than the enlarged lymph node, he experienced no clinical symptoms. Resection of the lymph node, which measured approximately 1.5 cm in diameter, revealed the diagnosis of NLPHL after review by an expert hematopathologist. Staging by sonography, bone marrow biopsy, and computed tomography showed no other disease locations. It was concluded that the patient had clinical stage IA NLPHL at diagnosis. Patient 1 opted, after being informed of treatment options, for active surveillance.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 37-year-old man (patient 2) presented with a single enlarged lymph node in his left axilla. The patient had no relevant comorbidities and no clinical symptoms apart from the single enlarged lymph node resulting in stage IA disease. He was initially treated with 2 cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) +20 Gy radiation, although radiation alone would nowadays be the preferred treatment for this patient.

Treatment of clinical stage IA NLPHL

In managing NLPHL, it is useful to differentiate clinical stage IA disease from other stage I/II cases. Clinical stage IA disease is mostly treated with local radiotherapy only, which has consistently been shown to be noninferior to a combined-modality treatment regarding outcome while sparing patients the toxicity of chemotherapy.10-13 More recent work has shown that shrinking the radiotherapy field in the treatment of stage IA NLPHL is possible, and involved-site radiotherapy is likely sufficient, although follow-up is still limited for these studies.14 The expected outcome of clinical stage IA patients with radiotherapy only is a 10-year progression-free survival (PFS) of over 85% with very little if any mortality due to NLPHL.10-13

An alternative approach that can be considered in patients not wanting radiotherapy is treating patients with an anti-CD20 antibody, such as rituximab.15 Disease control with a short course of 4 weekly doses of rituximab is excellent, with all patients responding in 1 study. However, patients tend to relapse over time, with a 10-year PFS of 51.1%,16 although these relapses can be easily salvaged in most cases, either by rituximab retreatment or radio- or chemotherapy. However, rituximab is clearly less effective than radiotherapy in stage IA disease.

Evidence for active surveillance—specifically in the situation of stage IA disease, in which the affected lymph node was completely excised—comes from a pediatric study, which reported a 5-year event-free survival of 77.1% and no deaths.17 Thus, active surveillance can be considered in stage I patients. Relapse risk is higher, but treatment might be avoided in a proportion of cases.

Treatment of clinical stage IB and II early-stage NLPHL

Most treatment approaches for clinical stage IB and II early-stage NLPHL have been extrapolated from the treatment of cHL. Given the distinct differences between NLPHL and cHL,2 this is far from ideal. For example, risk factors derived in cHL have been extrapolated to NLPHL but might not apply in the same way.

It is useful to first think in the broader categories of recommending radiotherapy only vs chemotherapy only vs combined modality as some evidence exists to help decide between these options. Studies have shown that long-term PFS is likely worse with radiotherapy only compared with combined modality when excluding stage IA.9,10,13,18 Similarly, chemotherapy only is likely worse.9,10,13,18 Thus, when optimizing long-term remission rate and cure likelihood is the primary treatment goal, combined-modality treatment is preferred in clinical stage IB and II early-stage NLPHL.

This leads directly to the question of the right chemotherapy regimen. Good evidence exists for ABVD followed by radiotherapy. The German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) has published large NLPHL cohorts treated with this approach using the GHSG risk groups and factors (Table 1) derived from cHL to decide which patients can be classified as early-stage favorable and thus should receive 2 cycles of ABVD followed by 20 Gy radiotherapy and which patients are classified as early-stage unfavorable und thus should receive 4 cycles of ABVD followed by 30 Gy radiotherapy.9 Even after long follow-up, outcomes were excellent. Ten-year PFS was 75% and 72%, and overall survival (OS) was 92% and 96% in early-stage favorable and unfavorable NLPHL, respectively.9 Thus, 2 to 4 cycles of ABVD followed by 20 to 30 Gy of involved-site or involved-field radiotherapy is a reasonable approach for clinical stage IB and II early-stage NLPHL.

The addition of rituximab to chemotherapy when using combined-modality treatment seems reasonable,19,20 as does the use of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) in clinical stage IB and II early-stage NLPHL, although published evidence relies on small patient numbers.21

In selected patients, a radiotherapy-only or chemotherapy-only approach might still be reasonable, depending on the individual patient. Like in stage IA NLPHL, a short course of rituximab or another anti-CD20 antibody can be used to reliably induce remissions with low toxicity, but relapse risk is higher than with combined-modality treatment.15,16 Active surveillance can also be an option. While many patients managed with active surveillance will ultimately progress and need treatment, it has been shown that an initial period of active surveillance does not seem to diminish the efficacy of the first active treatment and is associated with a very low risk of transformation and NLPHL mortality.22

Treatment of advanced-stage NLPHL

Like in early-stage NLPHL, treatment approaches developed in cHL have been extrapolated to advanced, clinical stage III/IV NLPHL. Therefore, both ABVD and BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone) variants can be considered reasonable treatment options for advanced-stage NLPHL. While using BEACOPP variants for NLPHL treatment constitutes using an intensive treatment regimen for a mostly nonaggressive disease, long-term disease control rates have been very good in large analyses. The GHSG recently reported on patients with advanced-stage NLPHL treated within the HD18 study, in which patients received positron emission tomography (PET)–guided treatment. Patients who achieved a negative PET scan after 2 cycles received 4 cycles of escalated BEACOPP and had a 5-year PFS of 90%, whereas those who had a positive PET scan after 2 cycles received 6 cycles of escalated BEACOPP and had a 5-year PFS of 70%. Across all patients, this PET-guided strategy resulted in a 5-year PFS of 82% with no deaths due to lymphoma reported.23

ABVD results in substantially worse outcomes, with 1 analysis reporting a 10-year PFS of only about 40%, although with good OS at 10 years of 84%.24 Although reported patient numbers are small, R-CHOP is probably a better option than ABVD in advanced NLPHL, with a 10-year PFS of 86% reported in 1 analysis.21 In this analysis, all patients responded to R-CHOP.21 It is difficult to say how R-CHOP compares to escalated BEACOPP regarding efficacy based on available data, but the limited data available for R-CHOP point to an efficacy similar to escalated BEACOPP with a less toxic regimen, making R-CHOP a very reasonable choice in this situation. This holds especially true when BEACOPP is seldom used and experience with this regimen is low. Alternative chemotherapy regimens that have been evaluated in few patients include BR (bendamustine, rituximab)25 and R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone).26 Both regimens can be considered in patients with contraindications to BEACOPP or R-CHOP.

Similar to early-stage NLPHL, active surveillance22 or treatment with an anti-CD20 antibody such as rituximab27 are reasonable options that often require other treatments later in the management of this particular patient but are unlikely to worsen long-term outcomes. They are good options for patients who have little disease burden, have no symptoms, and do not want to undergo more intense treatment right now.

Table 2 provides an overview of treatment options in NLPHL based on the patient's risk group.

CLINICAL CASE 1 (Continued)

Despite no active treatment beyond initial excision, patient 1 experienced 12 years of remission without any evidence of recurrence. However, ultimately, multiple small but enlarged lymph nodes became apparent and were progressing while the patient was still completely asymptomatic. A repeat biopsy specimen confirmed NLPHL, and the patient had clinical stage IIIA disease. The patient ultimately decided to undergo R-CHOP chemotherapy as the first active treatment for his disease and has been in complete remission for 3 years now.

Treatment of relapsed NLPHL

Evidence for the optimal treatment of relapsed NLPHL is scarce. In general, 4 approaches can be considered, ordered from least intense to most intense: active surveillance, anti-CD20 antibody treatment, conventional chemotherapy, and high-dose chemotherapy (HDCT) followed by autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). In general, rebiopsy is recommended to rule out transformation. Radiotherapy should be considered in addition to the abovementioned options when reasonable fields can be identified.28 Sometimes, even radiotherapy alone can be a good option for localized relapses. A recent study has evaluated ibrutinib in relapsed NLPHL, but 18-month PFS was disappointing at 56%.29 Options for relapsed NLPHL are summarized in Table 3.

In a GHSG analysis, patients treated with an anti-CD20 antibody or radiotherapy alone achieved a 5-year PFS and OS of 74% and 97%, respectively. Patients treated with conventional chemotherapy (± anti-CD20 antibody and ± radiotherapy) had a 5-year PFS and OS of 68% and 78%, respectively.28 A prospective study evaluating rituximab in relapsed NLPHL given for a short 4-week course showed a response rate of 94%.30 A study of another anti-CD20 antibody, ofatumumab, given for 8 weeks, resulted in a similar response rate of 96%.31 Recently, a registry analysis of HDCT + ASCT including 60 patients was published, showing that a 5-year PFS and OS of 66% and 87%, respectively, can be achieved with HDCT + ASCT in relapsed NLPHL.32 For most of these data, it is important to consider that patients were likely assigned to treatment based on their physician's assessment of disease severity at relapse, which could result in more aggressive treatments appearing worse because of selecting high-risk patients for them.

In relapsed patients, some information on the aggressiveness of an individual case is available in the form of time to relapse. This can be a good indicator to judge what might a good option for an individual patient. Other factors favoring less aggressive approaches are low disease and symptom burden and individual patient choice. In practice, patients with relapsed NLPHL can present in many ways, often with indolent lymphoma but sometimes also with more aggressive lymphoma.

CLINICAL CASE 2 (Continued)

After being in complete remission for 5 years, patient 2 experienced a disseminated relapse with lesions in the liver, spleen, vertebral bones, right shoulder blade, pelvic bones, and affected lymph nodes on both sides of the neck and in both axillae, in addition to periportal and celiac lymph nodes. Furthermore, the patient suffered from B-symptoms. A biopsy of a liver lesion was performed and revealed a relapse of NLPHL, despite the aggressive presentation being highly suggestive of transformation. This is also the reason why a more invasive liver biopsy was preferred in this case compared with a biopsy of a lymph node in the neck or axilla. NLPHL can present with occult transformation that might not be detectable in a peripheral, easily accessible lymph node. Therefore, it might be advisable to biopsy a bulky or intra-abdominal mass or an organ manifestation, all of which are unusual in NLPHL. Such a biopsy might be more likely to reveal transformation, if present. Because of the fulminant relapse resulting in stage IVB disease, it was decided together with the patient that aggressive treatment was warranted, and the patient underwent 6 courses of escalated BEACOPP, followed by 30 Gy radiation to liver lesions.

Unfortunately, the patient experienced another relapse after only 6 months, with progressive lesions in liver and spleen, abdominal lymph nodes, and multiple new osseous lesions. An experimental treatment with 7 cycles of the aPD-1 antibody nivolumab was tried based on its high efficacy in cHL33 but was not successful. Another rebiopsy ruled out transformation, which was again suspected based on the aggressive disease course. The patient then received 2 cycles of R-ICE (rituximab, ifospfamide, carboplatin, etoposide), followed by HDCT, using the BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) protocol followed by ASCT. This treatment led to a complete remission in patient 2 that is ongoing at 2 years of follow-up.

Treatment of transformation into aggressive B-NHL

Transformation into aggressive B-NHL is an important problem in the management of NLPHL, turning it into a disease with substantial mortality with a 10-year OS from the time of transformation of around 60% in 2 studies. Transformation rates have been reported at 7% to 12% after 10 years of follow-up in various studies.34,35 Treatment is individualized with both R-CHOP and high-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT being good options. Choice mainly depends on already received treatment and individual patient factors such as age and comorbidities. Other emerging options for the treatment of aggressive B-NHL such as immunotoxins or CART-T (chimeric antigen receptor T) cells36 can be explored as well in individual cases.

How to choose optimal management in the individual patient

Compared with cHL, evidence for the optimal treatment of NLPHL is limited. In general, it is important to consider that NLPHL is a mostly indolent disease, and treatment does not need to be rushed in most cases. Having said that, a few cases can present more aggressively, such as the case of patient 2 discussed here, and warrant more intense treatment. Apart from clinical features such as disease burden, local and systemic symptoms, and rate of progression over time, biological risk factors are emerging and can be considered. One of the most important biological risk factors emerging lately is variant histology.4-7 Fan et al4 described 6 distinct immunoarchitectural patterns, “classic” B-cell-rich nodular (pattern A), serpiginous nodular (pattern B), nodular with prominent extranodular L&H (lymphocytic and/or histiocytic cells) cells (pattern C), T-cell-rich nodular (pattern D), diffuse (TCRBCL [T cell rich B cell lymphoma]-like) (pattern E), and diffuse with a B-cell-rich background (pattern F). Sometimes, 2 or more patterns can be present in a case. Prognostically, patterns A and B (typical NLPHL) are associated with a better prognosis than patterns C to F (variant histology). In a large analysis of over 400 cases from GHSG trials, variant histology was present in 25% of cases and associated with a roughly 3-fold increased risk for relapse.5 In absolute numbers, this meant that only 7% of patients without experienced relapse after 5 years compared with 18% with variant histology.5 Other recent analyses have largely confirmed the negative impact of variant histology.4-7 In addition to variant histology, male sex and low serum albumin have been identified as risk factors in newly diagnosed NLPHL.5 Low serum albumin is an established negative prognostic marker in lymphoma in general, and its correlation with, for example, the International Prognostic Index (IPI) in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma shows that it can be seen as a marker of how much the host is affected by the lymphoma and thus its aggressiveness and spread.37

Another important aspect to consider is the likelihood of occult transformation. It has been reported that involvement of the spleen, liver, or intraabdominal lymph nodes can be indicative of occult transformation, meaning transformation into aggressive B-NHL is present but not detected in the biopsy specimen.27,35,38 If this is suspected, another biopsy, preferably of such a high-risk lesion, might be warranted. Also, a treatment approach that uses a regimen that has been proven to be effective in aggressive B-NHL, such as R-CHOP, should be considered in such cases.

Considering all this, I would recommend obtaining an expert histopathologic opinion, including assessment of variant histology, whenever possible and carefully examining disease and symptom burden in each patient as well as standard laboratory parameters. An initial period of observation can in certain cases be helpful to understand the natural rate of progression in a case. Taking all this information into account, either more or less aggressive treatment can be recommended from a disease point of view. Presence of variant histology should be recognized as an important risk factor and could justify more intensive treatment, although prospective evidence for such an approach is lacking in this rare disease. For stage IB/II disease with the presence of variant histology, combined modality treatment with radio- and chemotherapy might be even more warranted than in cases of typical NLPHL. For advanced-stage NLPHL with the presence of variant histology, R-CHOP, which also addresses possibly undetected (occult) transformation, might be a better option than a less intense regimen.

Other aspects that are important to consider are the patient's preference and individual host factors. Some patients will be happy to have their disease managed as a low-risk, more chronic condition and might not want burdensome, more aggressive treatment right now or have, for example, individual risk factors for late side effects of chemo- or radiotherapy. Other patients will want definitive, more aggressive treatment upfront, maximizing their individual chance of cure or at least very long-term remissions and accept necessary side effects.

Acknowledgment

I thank Dennis Eichenauer for the extremely helpful discussion of the cases presented here.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Sven Borchmann is a current holder of individual stocks in a privately held company and has membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees for Liqomics and is a consultant for Galapagos. These conflicts of interest are not related to this manuscript.

Off-label drug use

Sven Borchmann: nothing to disclose.