Abstract

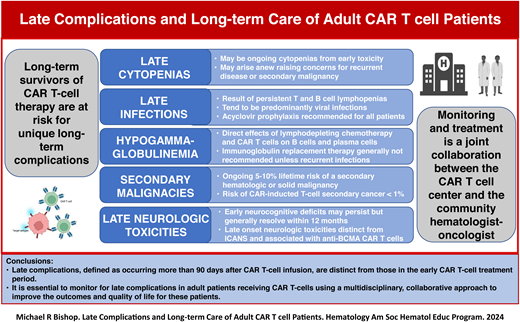

The success of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in adult patients with hematologic malignancies has resulted in a large number of long-term survivors who may experience late complications distinct from those in the early CAR T-cell treatment period. These late complications, defined as occurring more than 90 days after CAR T-cell infusion, include cytopenias, infections, secondary malignancies, and delayed neurotoxicities. Late cytopenias may be from prolonged recovery after lymphodepleting (LD) chemotherapy or arise anew, raising concerns for recurrent primary disease or a secondary malignancy. Cytopenias are treated with supportive care, hematopoietic cytokines, and, occasionally, hematopoietic stem cell support. LD chemotherapy profoundly affects B, T, and natural killer cells. CD19 and B-cell maturation antigen are expressed on normal B cells and plasma cells, respectively, and the targeting of these structures by CAR T-cell products can result in prolonged lymphopenias and hypogammaglobulinemia, making infection an ongoing risk. Late infections are predominantly due to respiratory viruses, reactivation of herpes viruses, and Pneumocystis jirovecii. Patients may require ongoing prophylaxis and immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Although responses may be blunted, vaccinations are generally recommended for most adult CAR T-cell patients. Both hematologic and solid secondary malignancies are a known risk of CAR T-cell therapy; retroviruses used to produce CAR T-cell products have resulted in T-cell cancers secondary to insertional oncogenesis. It is essential to monitor for late complications in adult patients receiving CAR T-cells by using a multidisciplinary approach between referring hematologist oncologists and cell therapy centers to improve the outcomes and quality of life for these patients.

Learning Objectives

Understand that adult CAR T-cell patients are at risk for a number of late complications (eg, infections, cytopenias) that can be life-threating and require continued monitoring and treatment.

Recognize unique long-term CAR T-cell therapy complications in adults such as delayed neurotoxicity and secondary malignancies.

Develop a multidisciplinary plan between cell therapy centers and referring hematologist oncologists to monitor and manage long-term complications in adult patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy.

CLINICAL CASE (Part 1)

A 56-year-old female was diagnosed with stage IIIB double-hit diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and received dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab (DA-EPOCH-R), as initial therapy. An interim PET-CT demonstrated significant decrease in the size and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avidity of her lymphadenopathy; however, a posttreatment assessment after 6 cycles of DA-EPOCH-R demonstrated progressive disease. She was referred to an academic medical center for treatment options. The patient did not have any significant comorbidities. She had good renal and hepatic functions; however, she had mild neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count [ANC] = 0.9 x 103/µL) and thrombocytopenia (platelets = 118 x 103/µL) secondary to recent chemotherapy. The consulting physician recommended chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel). She underwent successful leukapheresis and generation of her CAR T-cell product. She received lymphodepleting (LD) chemotherapy consisting of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide. Following axi-cel infusion, the patient experienced grade 2 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) that was successfully treated with tocilizumab, and she subsequently developed grade 1 immune effector cell– associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) that was successfully treated with a single dose of dexamethasone. She experienced prolonged grade 3 neutropenia that required supplemental granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) to maintain her ANC above 1.0 x 103/µL. PET-CT performed 30 days after infusion demonstrated near complete resolution of all FDG-avid lymphadenopathy. She required intermittent G-CSF to keep her ANC above 1.0 x 103/µL. Her 3-month post–CAR T-cell infusion evaluation demonstrated a complete remission without any FDG-avidity (1 on Deauville scale). Laboratory studies performed at this time demonstrated ANC = 1.1 x 103/µL, platelets = 42 x 103/µL, and serum IgG = 393 mg/dL; all other laboratory results were normal.

Introduction

CAR T-cell therapy has become an accepted treatment option resulting in improved progression-free and overall survival in a number of relapsed and refractory adult hematologic malignancies, and its use is expanding into solid tumors and nonmalignant disorders.1 The acute toxicities of CAR T-cell therapy, particularly CRS and ICANS, have been extensively described.2-5 However, as indications and use of CAR T-cell therapy have increased, so have reports of long-term survivors, and it has become increasingly apparent that there are a number of clinically significant, long-term complications that may affect this group of patients.6-8 Early recognition and knowledge of these long-term complications are important in patient selection, counseling, and management. Management of long-term complications in pediatric and young adults has been expertly reviewed.9 This paper will attempt to concisely review and provide guidelines for the monitoring and treatment of long-term complications after CAR T-cell therapy in adult patients.

Acute and medium-term toxicities

Acute toxicities related to CAR T-cell therapy are generally defined as occurring before and up to 28 days after the infusion of the CAR T-cell product. These toxicities may include, but are not limited to, toxicities related to bridging therapy, LD chemotherapy, tumor lysis syndrome, CRS, ICANS, immune effector cell–associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis–like syndrome (IEC-HS), and infections, which are predominantly bacterial.10,11 Subacute or medium-term complications are generally defined as occurring between 29 to 100 days after infusion.12 Intermediate-term toxicities may include infections (primarily viral), delayed-onset ICANS and IEC-HS, ongoing and new-onset cytopenias, and persistent lymphopenia with hypogammaglobulinemia.

Long-term complications

Long-term complications are generally characterized as occurring beyond 100 days after CAR T-cell infusion. The most common complications occurring during this time can include ongoing or new-onset cytopenias, persistent lymphopenias with hypogammaglobulinemia and resulting infections, secondary malignancies, and recurrence of the patient's primary malignancy. Although less frequent, late neurologic complications are a growing clinical concern.13 The majority of these complications will be observed by the referring hematologist oncologist and managed in collaboration with the cell therapy center.14

Late cytopenias

Cytopenias following CAR T-cell therapy, now termed immune effector cell–associated hematotoxicity (ICAHT), are commonly observed and may occur at any point after CAR T-cell treatment.15 A significant minority of patients have cytopenias that existed even before starting LD chemotherapy. Baird et al noted that 46.3% of patients had an absolute lymphocyte count less than 0.5 x 103/µL and 4.9% had an ANC less than 1.0 x 103/µL prior to starting LD chemotherapy.16 ICAHT is described as occurring in 3 phases: early (<30 days after infusion); prolonged (30-90 days after infusion); or late (>90 days after infusion).4,17 The majority of cytopenias resolve by the 90th day after infusion; however, it has been observed that late cytopenias have sometimes lasted several months and, in rare cases, beyond a year. The duration and severity of late cytopenias vary between CAR T-cell products and indications in adults. The incidences of late cytopenias have been reported to be 5%-16% for neutropenia, 7%-22% for thrombocytopenia, and 2%-3% for anemia.17 The majority of late cytopenias are the result of persistent earlier ICAHT. Higher grades of CRS and related cytokines (eg, IL-6) have been implicated in delayed hematologic recovery following CAR T-cell therapy.18 However, late cytopenias may also arise after having normal hematopoietic recovery in the early post–CAR T-cell period. The later development of cytopenias raises concerns for etiologies not typically observed with earlier ICAHT, particularly recurrent or secondary malignancy. The workup for late cytopenias includes assessment of medications capable of marrow suppression and for possible infection, particularly viral (cytomegalovirus [CMV], human herpesvirus 6, parvovirus B19). It is essential to perform a bone marrow examination to assess marrow cellularity and lineage function, assist in the evaluation of an infectious etiology, and determine if there is recurrence of original disease or a secondary malignancy. In cases of a paucity or lack of maturation in lineage-specific cells, a trial of lineage-specific cytokines should be entertained.19 General supportive measures, such as red blood cell and platelet transfusions, should be considered in all patients with late cytopenias. In cytopenias that are unresponsive to hematopoietic cytokines or in cases of marrow aplasia, a stem cell “boost” can be considered if the patient had previously undergone a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). For patients who underwent an autologous HSCT, this is only an option if they have cells in storage; for patients who have undergone prior allogeneic HSCT, it requires procuring new cells from the donor. In this latter situation, evidence of donor chimerism is required, and a method of CD34+ cell selection is recommended to avoid the risk of graft-versus-host disease. In patients with severe cytopenias unresponsive to all other interventions, an allogeneic HSCT can be considered.

Late infections

Infections are one of the most common causes of late morbidity and mortality in adult patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy. Similar to cytopenias, infections after CAR T-cell therapy have been described in 3 phases: the acute phase (0-28 days after infusion) is associated with severe neutropenia and lymphopenia; the delayed phase (29-90 days after infusion) is associated with impaired cellular and humoral immunity; and the late phase (>90 days after infusion) is associated with persistent B-cell aplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, and protracted CD4+ T cell recovery.16,20 The causes of infection can be multifactorial; these infections have been associated with underlying malignant disease, CAR T-cell product, patient age, and immune status and treatments prior to CAR T-cell infusion.12,21 Lymphodepleting chemotherapy results in near ablation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and natural killer cells, which can be prolonged.16 Additionally, CAR T-cell therapy, both anti-CD19 and anti–B-cell maturation antigen (anti-BCMA), can result in further B-cell aplasia and concomitant hypogammaglobulinemia. CD19 is expressed nearly universally on early lineage B cells but minimally on plasma cells, while BCMA is highly expressed by plasma cells.22 As such, anti-BCMA CAR-T cells may significantly impact preexisting pathogen-specific immunity while sparing naive and memory B-cell cells. These differences have been associated with differences in the types and the timing of infections, with a higher incidence of viral infections and more late infections with anti-BCMA CAR-T cells.

Late infections are predominantly respiratory viral infections, reactivation of herpes viruses, and Pneumocystis jirovecii infections, although both bacterial and fungal infections have been documented during this period. Respiratory viral infections occurring in the late phase are usually mild to moderate in severity and only rarely requiring treatment in an intensive care unit. Delayed reactivation of herpes viruses, including CMV, have been documented, although it is rare for patients to develop clinical CMV disease. However, the true incidences of CMV viremia and infection after CAR T-cell therapy are not established because routine CMV surveillance is inconsistent between centers. Another late infection of note is COVID-19, caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2. CAR T-cell patients are among groups at highest risk for COVID-19 infections, which are often severe and having prolonged viral clearance.21 The degree of lymphopenia independently correlates with COVID-19 clinical severity, and COVID-19-related mortality has been reported to be as high as 50%.23

Institutional and societal guidelines regarding infection prevention, prophylaxis, and vaccinations after CAR T-cell therapy are becoming increasingly available.12,13,20,23-25 However, there currently remains no consensus on prophylactic recommendations, which are largely based on expert opinion and extrapolated from evidence in other high-risk groups (Table 1). In terms of bacterial prophylaxis, most guidelines recommend a fluoroquinolone for a prolonged ANC <0.5 x 103/µL. Herpes simplex virus and varizell zoster virus (VZV) antiviral prophylaxis with either oral acyclovir (400 mg twice a day) or valacyclovir (500 mg twice a day) is almost universally recommended for at least 6 months and up to 12 months after infusion. Similarly, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) is generally recommended for Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis for a minimum of 6 months or until the CD4+ T-cell count is >200 cells/mL. A suggested regimen is oral double-strength TMP-SMX given 3 times a week. Alternatives for patients with a sulfa allergy or prolonged cytopenias include dapsone 100 mg orally daily, and if patients have a G6PD-deficiency, they may take oral atovaquone 1500 mg daily or aerosolized pentamidine monthly. There is no consensus about the optimal choice and duration of antifungal prophylaxis after CAR T-cell therapy. Guidelines suggest fluconazole 200-400 mg orally daily for patients with prolonged neutropenia (<0.5x 103/µL). A mold-active azole (eg, posaconazole) has been suggested as prophylaxis for higher-risk patients, including those who had prior allogeneic HSCT, those who had prior invasive aspergillosis, and those receiving corticosteroids.

Although prolonged lymphopenia and hypogammaglobulinemia after CAR T-cell therapy are thought to result in low responses to vaccines, the majority opinion is that vaccinations may still provide some protection and reduce the rates and severity of infections (Table 2).26,27 Inactivated vaccines should be administered at least 3 to 6 months after CAR T-cell infusion, and live vaccines are typically recommended ≥12 months after infusion. The use of B-cell, T-cell, and immunoglobulin levels to guide the timing of vaccination is logical, but there are minimal data to support this approach at present.20

The exceptions, for which early vaccination after CAR T-cell therapy is indicated, are influenza and COVID-19.27 Studies have shown that de novo antibody formation to COVID-19 was poor following early vaccination after a CAR T-cell infusion; however, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to COVID-19 were observed.28 Currently, American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT)/ASH guidelines recommend a complete series of mRNA-based COVID19 vaccines including a booster starting at 3 months after CAR T-cell therapy.29

Hypogammaglobulinemia and immunoglobulin replacement therapy

The incidence and severity of hypogammaglobulinemia can vary significantly, depending on the CAR T-cell product, with hypogammaglobulinemia rates of 46%-62% and 53%-75% at 12 months in patients receiving anti-CD19 and anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy, respectively.12 Immunoglobulin replacement therapy is a relatively standard practice among pediatric CAR T-cell programs; however, this practice has not been generally accepted in adult programs, nor is there consensus on recommendations for adult patients with severe hypogammaglobulinema.30,31 There is general agreement for immunoglobulin replacement therapy for adult patients with IgG levels less than 400 mg/dL and recurrent infections. However, the use of prophylactic immunoglobulin replacement for asymptomatic hypogammaglobulinemia is highly debated due to the lack of data on its efficacy and the associated side effects, costs, and logistical challenges with its administration. Most recommendations aim to maintain serum immunoglobulin levels above 400-500 mg/dL. Intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs) are usually given every 4 to 8 weeks at 0.4-0.5 gm/kg body weight, depending on the IVIG product. Alternatively, immunoglobulins may be given subcutaneously weekly at doses of 0.10-0.15 gm/kg. Cessation of immunoglobulin replacement should be guided by sustained IgG levels and functional B-cell recovery.

Secondary malignancies

Secondary malignancies have always been a concern with CAR T-cell therapy due to the potential risk of insertional oncogenesis by the retroviruses used to produce CAR T-cell products. This led regulators, such the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to mandate long-term surveillance of secondary malignancies for up to 15 years after cell infusion. Fortunately, these concerns have not been substantiated because, to date, an excessive incidence of secondary malignancies has not been observed with CAR-T cell therapy. The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research reported on 11 345 patients who received commercial CAR-T cells, of whom 8060 were enrolled in postauthorization safety studies aimed specifically to detect secondary malignancies.32 At a median follow-up time of 13 months, 565 (5.0%) secondary or subsequent malignancies were reported in 485 (4.3%) patients who had received commercial CAR-T cells, and 420 (5.2%) secondary or subsequent malignancies were identified in 357 (4.4%) patients from the postauthorization studies. However, as of December 31, 2023, the FDA had been notified of 22 cases of T-cell cancers that developed after treatment with a variety of CAR T-cell products.33 In 3 cases for which genetic sequencing had been performed, the CAR transgene was detected in the malignant clone. Among the more than 27 000 doses of the 6 approved CAR T-cell products administered in the United States, the overall incidence of T-cell cancers is approximately 0.1%. However, the true incidence of secondary T-cell malignancies may be underestimated, as there may be cases that were not reported or assumed to be recurrent B-cell lymphoma or myeloma and not biopsied when FDG-avid lesions were detected on PET-CT. The majority of secondary hematologic malignancies after CAR T-cell therapy are myeloid malignancies, while secondary solid malignances can be quite variable (eg, sarcomas, carcinomas) when nonmelanomatous skin cancers are excluded. Ghilardi et al assessed the overall risk of secondary malignancies in 449 patients who received commercial anti-CD19 or anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy at the University of Pennsylvania.34 At a median follow-up of 10.3 months, 16 patients (3.6%) were found to have secondary malignancies. The projected 5-year cumulative incidences were 15.2% for solid and 2.3% for hematological secondary malignancies, respectively.

The FDA subsequently stated that although the overall benefits of CAR T-cell products continue to outweigh their potential risks, patients on clinical trials receiving treatment with CAR T-cell products should be continuously monitored for new malignancies for the remainder of their lives. Leaders in the field and of various professional organizations and societies have stated their opinion that the benefits of CAR-T therapy continue to outweigh the potential risks in the vast majority of cases, and they encouraged cell therapy centers to support long-term follow-up recommendations by the FDA.32

Late neurologic toxicities

The overwhelming majority of neurologic toxicities occur and resolve within the first 30 days after CAR T-cell infusion. A small percentage of patients have subtle but persisting deterioration in neurocognitive performance occurring between days 30 and 90 with eventual recovery by 12 months.35 Additionally, there have been anecdotal reports of late onset ICANS.36,37 Ursu et al prospectively evaluated long-term neurologic toxicities in 65 adult patients who received anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy for non–Hodgkin lymphoma.38 Two years after treatment, no episodic disorders were noted, neuropsychological tests did not show any cognitive differences, and magnetic resonance images taken 2 years after infusion were similar to those at baseline.

Unique manifestations of late-onset neurotoxicity, distinct from ICANS, have been observed following anti-BCMA CAR-T cell therapy for multiple myeloma. A movement and neurocognitive disorder with features of Parkinsonism was reported in 5% of patients treated with ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel) in the CARTITUDE-1 trial.39 The disorder was described as occurring at a median of 17 days (range, 3-94 days) following recovery from CRS and ICANS, not responding to immunosuppressive and dopaminergic agents, and having a progressive and occasionally fatal course. The cause of this disorder in not completely understood, but it is thought to possibly be on-target, off-tumor toxicity against BCMA-expressing neurons and astrocytes in the basal ganglia. Risk factors associated with the disorder include high tumor burden, severe CRS or ICANS, and higher CAR-T cell expansion and persistence. As a result, it is recommended that patients receiving anti-BCMA CAR-T cell therapy undergo extended neurologic monitoring until at least 12 months after infusion.

Late psychosocial issues

Long-term survivors of CAR-T cell therapy have been found to have self-reported data regarding mental health, fatigue, and social function similar to those of the general population. Ruark et al used patient-reported outcomes, including Patient- Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) measures, to assess neuropsychiatric and other patient- reported outcomes in 40 patients 1 to 5 years after anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy.40 The mean T scores of PROMIS domains of global mental health, global physical health, social function, anxiety, depression, fatigue, pain, and sleep disturbance were not clinically different from the mean in the general US population. However, 19 patients (47.5%) reported at least 1 cognitive difficulty or clinically meaningful depression or anxiety, and 7 patients (17.5%) scored ≤40 in global mental health. Fifteen patients (37.5%) reported cognitive difficulties after CAR T-cell therapy, and there was a trend for an association between acute neurotoxicity and self-reported cognitive difficulties after CAR T-cell therapy (P = .08). The authors concluded that although overall neuropsychiatric outcomes were good in the majority of long-term survivors after CAR T-cell therapy, there was still a significant number that would likely benefit from mental health services. Although larger studies are needed to confirm these findings, the screening and support for mental health disorders should be an essential part of long-term follow-up care of CAR T-cell recipients.

Conclusions

After CAR T-cell therapy, the majority of long-term survivors will fortunately have full resolution of prior toxicities and enjoy a relative high quality of life; however, a significant minority will experience late toxicities, which can be life-threatening. Indeed, the incidence of nonrelapse mortality has been to be reported as high as 16%, primarily from late infections and secondary malignancies.41,42 To identify and manage late CAR T-cell toxicities, it is necessary to establish a monitoring plan through a strong collaboration with a community hematologist oncologist and a cell therapy center (Table 3). The cell therapy center optimally should have a multidisciplinary long-term follow-up clinic for CAR T-cell patients with staff and resources capable of addressing late complications, such as secondary malignancies and psychological health, as well as documenting patient-reported outcomes. The referring hematologist oncologist needs to be aware of these resources, and a joint long-term follow-up plan needs to be established. This joint collaboration will lead to improved outcomes and quality of life for patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Michael R. Bishop: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Michael R. Bishop: nothing to disclose.