Abstract

The remarkable improvement in survival among individuals with hematological malignancies receiving chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has highlighted the growing unmet need to incorporate patient-centered assessments in management guidelines for these patients. That CAR T-cell therapy is associated with unique toxicities and relatively high symptom burden in the first few weeks after cell infusion is well known. Magnifying the patient's voice by using patient-reported outcomes (PROs) might support personalized intervention in the acute-care setting, optimize the use of medical resources, improve satisfaction with therapy, and enhance survival benefit. However, various factors impede PRO use in routine patient care: (1) the feasibility of PRO assessment during the acute phase of treatment, especially in patients experiencing neurological toxicities, is not well established; (2) although PROs are widely used in drug- development trials, the assessment tools used in clinical trials primarily inform quality-of-life or safety comparisons among study arms and are rarely the proper tools for assessing and capturing clinically meaningful adverse events that should be monitored in routine patient care; (3) PRO data that could guide how best to monitor and capture the delayed effects of CAR T-cell therapy in long-term survivors are limited. There is a pressing need to overcome these barriers to integrating evidence-based PROs into standard-of-care guidelines for patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy. In this review, we present the current state of PRO utilization in CAR T-cell therapy. We also discuss practical approaches and future directions for successful implementation of PROs in the care of patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy.

Learning Objectives

Review current experience with PROs in patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy for hematological malignancies

Describe the importance of and the difficulties associated with the routine use of PROs for symptom and toxicity monitoring after CAR T-cell therapy

Present practical strategies for implementing PROs in the routine care of patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy

Introduction

The approval of various chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies since 2017 has created a paradigm shift in standard practice for managing several advanced hematological neoplasms, including certain subtypes of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and multiple myeloma. These novel therapies are associated not only with excellent early response but in some cases with durable remission and even potential cure. Despite these positive outcomes, however, CAR T-cell therapy is also associated with unique and potentially serious toxicities, such as cytokine release syndrome (CRS), neurotoxicity, cytopenia, infection, and other immune effector cell (IEC)–associated hyperinflammatory syndromes.

As we now know from drug development efforts and real-world experience in cancer management, there is a pressing need to integrate patient-reported outcomes (PROs) into standard-of-care management algorithms for CAR T-cell therapy.1 Recent efforts have focused on standardizing methods for grading and managing the significant CAR T-cell therapy toxicity-driven symptom burden,2 whereas how best to use PROs to support more efficient patient care remains an important research agenda, in terms of both patient benefit and clinical benefit. For example, the early identification of CAR T-cell therapy–related toxicities is imperative for timely intervention and better outcomes. Moreover, because late toxicities and complications can develop, close monitoring is required for several years to capture any events of interest.

Here, we focus on current research, clinical experience, methodologies, and infrastructure supporting the use of PROs in the care of patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy for hematological neoplasms.

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 54-year-old woman in otherwise good health developed acute-onset lower back pain. She was diagnosed with high-risk immunoglobulin A lambda myeloma with pathological fracture to T12. She underwent standard induction myeloma therapy followed by an autologous stem cell transplant (auto-SCT). She achieved complete response thereafter but relapsed 3 years later while on maintenance therapy. After several lines of subsequent treatment failed, approximately 4.5 years post diagnosis she underwent standard-of-care B-cell maturation antigen–directed CAR T-cell therapy for disease progression. On day 9 after cell infusion, the patient developed grade 1 CRS, which improved with supportive management during hospitalization. The patient was discharged in stable condition on day 14, after which she was monitored in the clinic 2 to 3 times per week. On day 23 she noticed double vision but did not report it to her providers until she was seen in the clinic 3 days later. Her caregiver reported that she also had shaky hands while eating and an unsteady gait while walking. The patient was immediately admitted for further evaluation and expedited management, with plans to rule out progressive disease vs treatment-related toxicities.

Understanding the impact of intense cancer treatment on patients: the symptom science

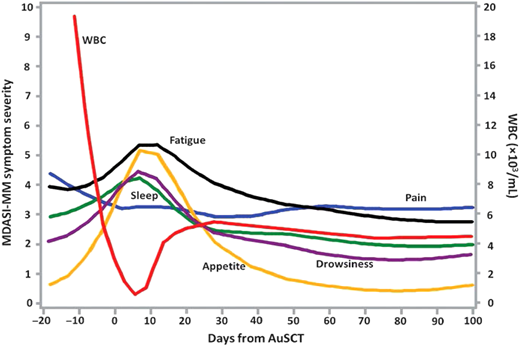

The symptoms experienced by cancer patients and survivors cause significant distress, can affect patient adherence to treatment, and can impair patient functioning, rehabilitation, and recovery.3 Self-reporting of symptom severity and functional impairment could be vital to improving patient care and well-being, especially for those undergoing aggressive cancer treatment. The growing field of symptom science has shown that longitudinal studies using multisymptom assessment tools are both feasible and sensitive to changes in symptom trajectories over time for different cancer treatments. For instance, our group found that even very ill patients undergoing auto-SCT or allogeneic SCT can complete PRO assessments frequently and repeatedly (Figure 1).4,5 In multiple myeloma patients who underwent auto-SCT, 35% had a persistently high symptom burden with severe symptoms 3 to 9 months post transplant, despite having controlled disease.4

Profiles of major symptom burden for the first 100 days after auto-SCT for multiple myeloma. WBC, white blood cell count.

Profiles of major symptom burden for the first 100 days after auto-SCT for multiple myeloma. WBC, white blood cell count.

The utility of PROs in oncology care is further supported by the value of a well-defined symptom burden in predicting poor clinical outcomes. We have shown that the severity of shortness of breath or coughing predicted grade 2-plus radiation pneumonitis after chemoradiotherapy in patients with non–small cell lung cancer and that baseline moderate to severe coughing (rated 4+ on a 0-10 scale) plus poor performance status predicted poorer overall survival.6,7

Acute toxicities of CAR T-cell therapy: a unique symptom burden

Case 1 highlights some of the acute/early unique toxicities associated with CAR T-cell therapy. CAR T-cell expansion can lead to massive cytokine overproduction, which triggers various hyperinflammatory syndromes—eg, CRS, IEC-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), or IEC-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis–like syndrome—during the first few days and weeks after cell infusion.8-11

The symptoms induced by proinflammatory cascade have been well studied in animal models of “sickness behavior” and in humans during the acute phase of aggressive cancer treatment.3 A frequently seen symptom cluster includes fatigue, pain, distress, poor appetite, drowsiness, sleep disturbance, and possibly chills and fever.4 An observational cross-sectional study conducted by our group captured 18 severe symptoms during the first 3 months after CAR T-cell therapy (Table 1).12 A longitudinal symptom study investigating the frequency of PROs rated 7 or greater on a 0 to 10 scale across different time periods (such as within 30 days of infusion and 30-90 days after) is needed to enhance the precision of potential alerts that would trigger the necessary care from professionals. Patients who experience grade 2 to 4 adverse events report substantial symptom burden and frequently require more recovery time (up to several months) after receiving CAR T-cell therapy, highlighting the importance of close monitoring and active care in the outpatient setting for these high-risk patients.

Patient-reported severe symptoms on MDASI-CAR during the 12 months after CAR T-cell therapy

| . | % Severe symptoms on MDASI-CAR (≥7 on a 0-10 scale) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | ≤30 days after infusion . | 31-90 days after infusion . | >90 days after infusion . |

| MDASI-Core itemsa | |||

| Pain | 21.4 | 15.4 | 5.3 |

| Fatigue | 32.1 | 38.5 | 5.3 |

| Nausea | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Disturbed sleep | 14.3 | 15.4 | 10.5 |

| Distress | 3.6 | 7.7 | 0.0 |

| Shortness of breath | 3.6 | 7.7 | 5.3 |

| Difficulty remembering | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Lack of appetite | 14.3 | 30.8 | 0.0 |

| Drowsiness | 17.9 | 38.5 | 10.5 |

| Dry mouth | 21.4 | 23.1 | 0.0 |

| Sadness | 3.6 | 7.7 | 0.0 |

| Vomiting | 0.0 | 7.7 | 0.0 |

| Numbness | 0.0 | 7.7 | 0.0 |

| MDASI-Interference itemsb | |||

| Activity | 25.0 | 15.4 | 10.5 |

| Mood | 7.1 | 7.7 | 10.5 |

| Work | 10.7 | 15.4 | 10.5 |

| Relations with others | 7.1 | 0.0 | 10.5 |

| Walking | 14.3 | 7.7 | 10.5 |

| Enjoyment of life | 14.3 | 15.4 | 10.5 |

| MDASI-CAR Module items (CAR T-cell therapy-related symptoms)a | |||

| Diarrhea | 7.1 | 23.1 | 0.0 |

| Tremors | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Fever or chills | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Headache | 10.7 | 15.4 | 0.0 |

| Balance or falling | 7.1 | 7.7 | 0.0 |

| Dizziness | 3.6 | 23.1 | 0.0 |

| Coughing | 3.6 | 15.4 | 5.3 |

| Change in sexual function | 14.3 | 23.1 | 5.3 |

| Problem with paying attention (concentrating) | 3.6 | 23.1 | 0.0 |

| Difficulty speaking (finding the words) | 3.6 | 7.7 | 5.3 |

| . | % Severe symptoms on MDASI-CAR (≥7 on a 0-10 scale) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | ≤30 days after infusion . | 31-90 days after infusion . | >90 days after infusion . |

| MDASI-Core itemsa | |||

| Pain | 21.4 | 15.4 | 5.3 |

| Fatigue | 32.1 | 38.5 | 5.3 |

| Nausea | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Disturbed sleep | 14.3 | 15.4 | 10.5 |

| Distress | 3.6 | 7.7 | 0.0 |

| Shortness of breath | 3.6 | 7.7 | 5.3 |

| Difficulty remembering | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Lack of appetite | 14.3 | 30.8 | 0.0 |

| Drowsiness | 17.9 | 38.5 | 10.5 |

| Dry mouth | 21.4 | 23.1 | 0.0 |

| Sadness | 3.6 | 7.7 | 0.0 |

| Vomiting | 0.0 | 7.7 | 0.0 |

| Numbness | 0.0 | 7.7 | 0.0 |

| MDASI-Interference itemsb | |||

| Activity | 25.0 | 15.4 | 10.5 |

| Mood | 7.1 | 7.7 | 10.5 |

| Work | 10.7 | 15.4 | 10.5 |

| Relations with others | 7.1 | 0.0 | 10.5 |

| Walking | 14.3 | 7.7 | 10.5 |

| Enjoyment of life | 14.3 | 15.4 | 10.5 |

| MDASI-CAR Module items (CAR T-cell therapy-related symptoms)a | |||

| Diarrhea | 7.1 | 23.1 | 0.0 |

| Tremors | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Fever or chills | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Headache | 10.7 | 15.4 | 0.0 |

| Balance or falling | 7.1 | 7.7 | 0.0 |

| Dizziness | 3.6 | 23.1 | 0.0 |

| Coughing | 3.6 | 15.4 | 5.3 |

| Change in sexual function | 14.3 | 23.1 | 5.3 |

| Problem with paying attention (concentrating) | 3.6 | 23.1 | 0.0 |

| Difficulty speaking (finding the words) | 3.6 | 7.7 | 5.3 |

Symptom items were rated at their worst in the past 24 hours on a 0 to 10 scale: 0 = no symptom; 10 = as bad as you can imagine.

Interference items were rated at their worst in the past 24 hours on a 0 to 10 scale: 0 = no interference; 10 = interfered completely.

Bold indicates that more than 10% of patients reported the symptom as severe (≥7 on a 0-10 scale).

Modified from Wang et al.12

Current outpatient practice after hospital discharge for CAR T-cell therapy patients includes close follow-up in specialized clinics 2 to 3 times per week for the first 30 days after cell infusion. Thereafter, patients are followed less frequently and generally are advised to contact their clinicians or go directly to an urgent/emergency care center if they develop severe symptoms. A more helpful strategy might be frequent electronic PRO (ePRO) monitoring, at least 2 to 3 times weekly in the first 30 days, to identify any early- and intermediate-term toxicities, functional limitations, and/or neuropsychiatric effects. This approach could allow for personalized intervention in the acute-care setting, guarantee more responsive cancer care, and reduce the number of emergency center visits, hospitalizations, and days spent in the hospital.

The development and severity of CRS, ICANS, and other toxicities remain unpredictable despite some correlation with certain pretreatment risk factors and inflammatory markers. Hence, we speculate that frequent PRO assessment early after CAR T-cell therapy has great potential for capturing the earliest toxicity-related symptoms so that timely, effective management can be delivered. Our Clinical Case 1 patient waited 3 days before reporting diplopia and other concerning symptoms that could have indicated serious CAR T-cell therapy–related neurological toxicities. These symptoms could have been captured and reported instantly if ePROs had been implemented at the time. Because early intervention is crucial for better outcomes in CAR T-cell therapy patients, the prospective evaluation of risk-adapted strategies for capturing and reducing patient toxicity profiles while maintaining treatment efficacy should be a clinical and research priority.

Neurocognitive disorders related to CAR T-cell therapy can range from mild cognitive impairment to severe neurotoxicity, representing a special challenge that could hinder PRO implementation in patient care. The clinical utility of PROs among these patients has not been reported. The US Food and Drug Administration has raised concerns about PRO feasibility when patients have significant cognitive impairment.13 Similar concerns exist around missing data in CAR T-cell patients when they develop severe neurotoxicity or CRS.14 Our own pilot study in patients with grade 2 to 4 CRS/ICANS supported using a treatment-specific symptom assessment tool in patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy,12 although this needs to be confirmed in a larger longitudinal study and more importantly in patients with grade 3 to 4 ICANS. Additionally, the proxy reporting of symptom burden by caregivers using the same PRO assessment tool has not been well evaluated in these patients.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 30-year-old man with relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma had a history of anxiety related to his cancer diagnosis but otherwise was in good medical and functional condition. Three lines of previous therapy had failed, and he was referred to our tertiary cancer center for standard-of-care CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy. He was followed closely during the first month after lisocabtagene-maraleucel infusion, during which time he developed minimal toxicities and achieved complete remission. At 12 months, remission was sustained. However, at month 13 the patient's wife contacted our office with concerns that sleep disturbance and a depressed mood were causing her husband to miss work.

Late effects of CAR T-cell therapy: the need for symptom monitoring

As CAR T-cell therapy expands to new disease indications and the number of long-term survivors steadily increases, there is growing recognition of the need to appropriately assess symptom burden and manage the late effects of CAR T-cell therapy. Late effects can be related to persistent and/or new symptoms related to neurotoxicity, prolonged cytopenia, delayed immune reconstitution and recurrent infection, subsequent malignancy, and psychological distress, among others.15,16 In the 3 months after infusion, 10% of patients are at risk for severe neurological and psychiatric morbidity.16,17 Our Clinical Case 2 patient experienced a late-onset sleep disturbance and depressed mood that affected his work performance. These late effects are consistent with our finding that more than 10% of patients experience sleep disturbances and mood changes within 3 months of infusion (Table 1)12; in another study, approximately 50% of long-term survivors reported at least 1 clinically meaningful negative neuropsychiatric outcome (anxiety, depression, cognitive difficulty), suggesting that a significant number of patients would probably benefit from mental health services after CAR T-cell therapy.18 Younger age, pretreatment anxiety or depression, and acute neurotoxicity were identified as possible risk factors for long-term neuropsychiatric problems in this patient population.18

Unfortunately, patients at home frequently do not report symptoms, except in emergency situations.19 Proactive PRO tools would help patients and caregivers report certain nonurgent symptoms, which could have great value in capturing subtle long-term toxicities in a timely manner so that proper interventions can be implemented, thereby improving long-term outcomes and overall patient well-being.

PRO-based clinical research: assessment tools in CAR T-cell therapy

There remains a compelling need for a mechanism that allows patients and caregivers to self-report symptoms to their treatment teams. Studies have shown that using patient- and clinician-friendly PRO assessments can ensure close monitoring of patients at early, actionable times, thereby facilitating symptom-burden control and allowing for faster functional recovery after intense treatment, such as CAR T-cell therapy. To facilitate the use of PROs in clinical care after CAR T-cell therapy,20 an ideal symptom assessment tool must be fit for purpose (ie, tailored to the unique toxicity profile of CAR T-cell therapy during and after treatment), and it must be reliable, valid, and able to detect change within a short recall time frame.21

In August 2018, a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services panel highlighted 4 PRO tools for consideration in CAR T-cell therapy1: (1) the PRO-based version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, which has 114 items designed to measure adverse events in general22; (2) the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 Questionnaire, which has been used as a generic health-related quality-of-life (QOL) tool in phase 3 clinical trials and patient care but has only 8 symptom items that capture acute toxicities23; (3) PROMIS, which has been used to measure patient health-related QOL and health outcomes in a computer-adaptive framework to increase assessment precision24; and (4) the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI),24,25 which assesses multiple cancer-related symptoms and functional impairment. Despite several CAR T-cell therapy clinical trials, reports characterizing specific symptoms driven by CAR T-cell therapy–associated toxicities are limited, and the PRO measures used are often suitable only for measuring QOL outcomes or for safety data reporting. The most-used PRO tools are generic measures, such as the PROMIS-29, the EQ5D, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 Questionnaire, and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy.

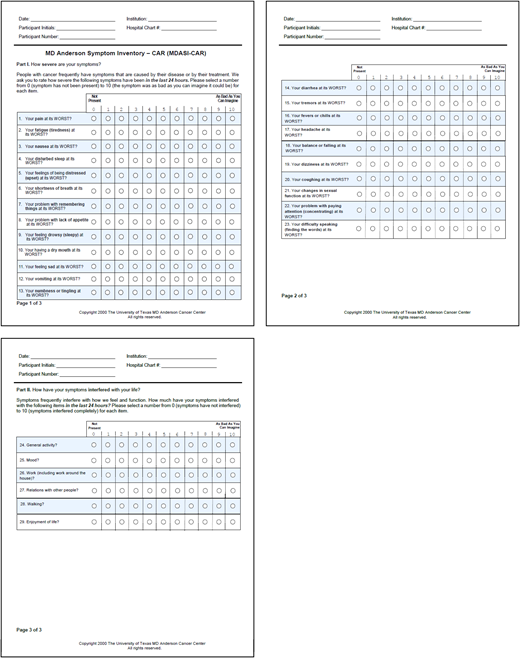

To further explore these shortcomings, we conducted 2 studies,12,26 1 qualitive and 1 quantitative, in patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy. These studies supported the hypothesis that a “one-tool-fits-all” approach based on a QOL measure is insufficient in this patient population. Therefore, we developed and validated a new MDASI module, the MDASI-CAR,27 to assess symptom burden in patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy. The MDASI-CAR comprises the MDASI's 13 core symptom items and 6 symptom interference items, along with 10 CAR T-cell therapy–related symptoms (Figure 2). The MDASI-CAR's 24-hour recall period is sensitive to rapid treatment-related changes in symptom severity and functional status.

The MDASI-CAR, a psychometrically validated multisymptom assessment tool.

Notably, even a comprehensive, concise, validated tool like the MDASI-CAR might be too burdensome for patients during the difficult time immediately after infusion. Therefore, brief, fit-for-purpose, time-sensitive, toxicity-driven PRO scales may be needed during that specific period, not only to improve outpatient care and optimize patient and caregiver support but also to minimize the need for hospitalization and facilitate earlier hospital discharge.

Good clinical practice: considering PROs as outcome measures

Investigators and clinicians are highly interested in using PROs for CAR T-cell therapy in both clinical research and standard practice. Choosing the most appropriate PRO tool can be challenging and relies on several factors, including the tool's primary focus (eg, symptoms, functioning, quality of life), validity (eg, psychometric validity, linguistic validity), and burdensomeness, among others. Researchers exploring clinical outcomes should give special consideration to primary objectives and end points that could translate into meaningful clinical outcomes.

On the other hand, successfully implementing PROs in routine care will require attention to safety, feasibility, quality control, and staff expertise and training and a platform for database setup and interpretation of results. A multidisciplinary team that includes hematologists experienced in CAR T-cell therapy, seasoned PRO experts, and biostatisticians is often helpful. Data supporting the greater reliability and validity of ePROs compared with paper suggest the enhanced utility of electronic platforms for routine PRO monitoring between clinic visits, as ePROs reported during and after treatment can alert clinicians to the earliest symptoms of concern, reduce the severity of symptoms, avoid symptom worsening, improve treatment adherence, and enhance patient satisfaction.28-31 An app on a personal wearable device could improve routine use, especially for tracking high-risk individuals after hospital discharge. Moreover, combining function-related PROs with objective measures (such as counts of walking steps) would provide a comprehensive measure of patient functioning.32

Further methodology and infrastructure considerations for monitoring CAR T-cell therapy–related PROs

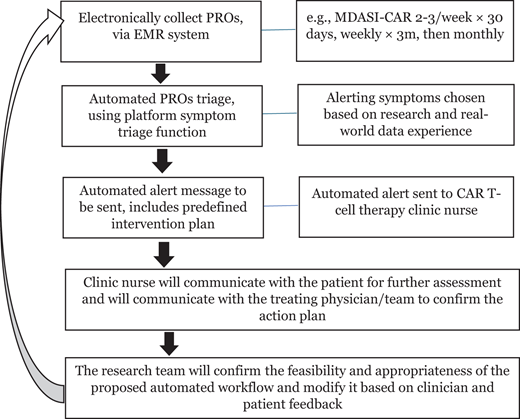

Methodologies for integrating PROs into routine clinical care (ie, ePRO-based pathways with symptom monitoring to capture potential complications and linkage to on-time triage and management) have been investigated in various fields of patient care but have not been adopted for CAR T-cell therapy. Importantly, real-world patient-reported experiences after standard-of-care CAR T-cell therapy may differ from results reported in clinical trials, given the restricted patient-selection criteria in clinical trials. Critical PRO methodological information that should be built into an ePRO pathway includes the following: (1) a brief set of clinically relevant symptom items; (2) evidence-based cut points for certain symptoms to trigger triage and possible intervention; (3) specific professionals responsible for responding to alerts, depending on the phase of treatment in the clinic; and (4) the standard or current consensus management algorithm. Recent research has shown the feasibility, utility, and value of using such well-defined clinically meaningful PROs as parameters for patient care.29,33

The infrastructure required for PROs to be effective has also been discussed.34 Topics under consideration include the following: which methods of PRO data collection (for example, in-hospital or at home via an existing patient portal such as MyChart or through the patient's personal device) will be most convenient and less disruptive for patients in terms of frequency of assessments, data safety, reporter bias, and combining PROs with validated wearable devices (such as for examining postoperative sleep patterns).35

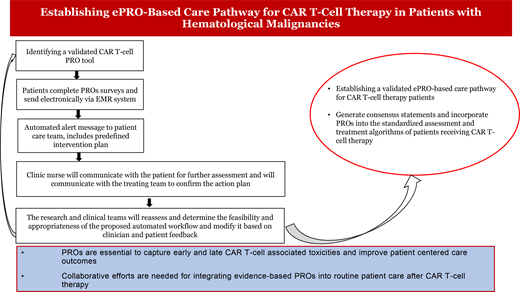

Figure 3 presents a proposed patient care pathway for integrating ePROs into routine patient care. This pathway aims to overcome various barriers that prevent ePRO implementation into practice for CAR T-cell patient care, including lack of a “user manual” with algorithms for interpreting PRO data in a busy clinical setting and lack of knowledge about the ability of cognitively impaired patients with high-grade CRS/ICANS to use PRO instruments.36 Accumulated data would support updating clinical CAR T-cell management guidelines and consensus to account for PROs.8,9,37

ePRO-based patient care pathway for applications in CAR T-cell therapy. EMR, electronic medical record.

ePRO-based patient care pathway for applications in CAR T-cell therapy. EMR, electronic medical record.

Conclusion

The advances made in PRO assessment and the associated improvements in patient outcomes are sufficient to justify rapid PRO implementation in routine patient care for a variety of cancer treatments. In clinical research, PROs contribute to precision, efficiency, standardization, and successful collaboration among study centers. However, more work is needed before PROs can be broadly incorporated into routine patient care in CAR T-cell patients. Proper implementation requires close coordination among clinicians, symptom researchers, and electronic health system designers to capture toxicity development early so that timely interventions can be introduced. The resulting improvements in symptom burden and treatment tolerability will eventually translate into better outcomes—for example. better treatments and interventions, more accurate reflection of the patient's voice and wishes about their care, enhanced patient satisfaction with therapy, better QOL, and, potentially, longer survival.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Xin Shelley Wang: no competing financial interests to declare.

Samer A. Srour: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Xin Shelley Wang: nothing to disclose.

Samer A. Srour: nothing to disclose.