Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT) remains a cornerstone in the treatment of high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), yet optimal patient selection is challenging in the era of rapidly changing modern therapy. Refined molecular characterization allows for better risk assessment, sparing low-risk patients from allo-HCT toxicity while identifying those who may benefit from intensified approaches. Measurable residual disease (MRD) has emerged as a powerful predictor of relapse irrespective of treatment strategy, challenging the necessity of transplant in MRD-negative patients. Further, expanded donor options, particularly haploidentical transplantation coupled with reduced intensity conditioning, have extended the applicability of allo-HCT to a broader range of patients. Finally, immunotherapies and targeted treatments are increasingly integrated into both initial and relapsed treatment protocols yielding deep remission and allowing for successful transplant in patients with a history of advanced disease. In this review, we provide an overview of the contemporary role of transplant in adult patients with ALL, focusing on indications for allo-HCT in first remission, optimal sequencing of transplant with novel therapies, and advancements in donor selection and conditioning regimens.

Learning Objectives

Identify indications for transplant in first complete remission in adult patients with ALL

Recognize the increased availability of donors with the use of post-transplant cyclophosphamide

Review optimal sequencing for transplant in the setting of novel immunotherapies in relapsed/refractory ALL

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 25-year-old Hispanic man, otherwise well, presents with fevers and ultimately is diagnosed with Philadelphia chromosome (Ph)-negative B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) detects an IGH::CRLF2 gene fusion consistent with Ph-like ALL. He receives hyper-CVAD induction (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone) and achieves an MRD-negative complete remission. No matched unrelated donor is identified, and his brother is an HLA-haploidentical match.

Refinement of ALL disease risk by molecular genetic profile

Allo-HCT has long been used as a strategy to minimize relapse risk in patients with high-risk ALL. What constitutes “high risk” and merits the risk of allo-HCT continues to evolve in the era of modern therapy and an increasingly complex genomic landscape of ALL. Recurring molecular genetic features of ALL and their prognosis are reviewed in detail in the fifth edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues (Table 1).1 Herein, we focus on several key subtypes of ALL for consideration of transplant in first complete remission (CR1) and highlight recent advancements in conditioning and donor selection.

High-risk subtypes of acute lymphoblastic leukemia

| Disease entity . | Genetic testing . | Additional genetic changes . | Frequency . | Prognostic relevance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypodiploid Near-haploid (24-31 chromosomes) Low-hypodiploid (32-39 chromosomes) High-hypodiploid (40-43 chromosomes) | Karyotyping/FISH | RTK and RAS pathway mutations (NF1), IKZF3 deletion in near-haploid. RB1, CDKN2A/B, IKZF2 deletions, TP53 mutations (up to 50% TP53 mutations are germline) in low-hypodiploidy | Approximately 2% of childhood, rare in adults are near-haploid; approximately 1% of childhood, 10% of adult are low hypodiploid | Unfavorable for near-haploid and low-hypodiploid |

| iAMP21 | FISH for ETV6::RUNX1 used to identify iAMP21 | Defined by 5 copies of RUNX1 per cell, with ≥3 copies on a single abnormal chromosome 21 | 1%–2% in children, rare in adults | Unfavorable; outcomes improve with intensive chemotherapy |

| BCR::ABL1rearranged | Karyotyping/FISH/ PCR/RNA-seq for detection of BCR::ABL1 fusion | IKZF1 deletions (80%) co-occurring with deletions of PAX5 and CDKN2A/B, EBF1 mutations in 14% | 2%–5% in children, 6% in adolescents and young adults, and >25% in adults | Unfavorable; incorporation of TKI targeted therapy has improved outcomes. IKZF1-rearranged unfavorable |

| BCR::ABL1-like (Ph-like) | Whole transcriptome or targeted RNA-seq. When unavailable, derivative methods like TaqMan low-density arrays, multiplex PCR, and FISH panels using break-apart probes may be used | a. ABL-class fusions: Fusions involving ABL1, ABL2, CSF1R, LYN, PDGFRA, PDGFRB b. JAK/STAT abnormalities: These include enhancer hijacking of promoter regions (IGH::CRLF2, P2RY8::CRLF2), fusions and mutations (eg, JAK2 R683G or JAK1 V658F) c. Miscellaneous fusions involving FGFR1, NTRK3, etc. in JAK1/JAK2/JAK3 genes and fusions/truncating deletions of EPOR (eg, EPOR::IGH) frequently associated with IKZF1 deletions and copy number alterations in B-lymphoid transcription factors. Activating mutations involving cytokine receptors (eg, IL7R and CRLF2) also constitute an underlying genetic abnormality | Frequency increases with age: 10%–15% of children, 20%–25% of adult, 50%–60% of patients with Down syndrome | Unfavorable; associated with high minimal residual disease positivity rates. Targeting the underlying genetic abnormality may improve survival rates |

| KMT2Arearranged | Karyotyping/FISH/ Global or targeted RNA sequencing | More than 90 partners of KMT2A described of which AF4, MLLT3, MLLT1, MLLT10, and MLLT6 are common | 70%–85% of infant, 2% of childhood and adult | Unfavorable |

| ETV6::RUNX1-like | Whole transcriptome or targeted RNA sequencing. Increased frequency of ETV6-like B-ALL may be seen in patients with germline ETV6 mutation | Fusions or copy number alterations involving ETV6, ERG, FLI1, IKZF, or TCF3 are common | 3% of childhood, uncommon in adults | Possibly unfavorable |

| TCF3::HLF | Global or targeted RNA sequencing for uncommon partners | Accompanying genetic lesions, including deletion of B-cell differentiation genes (PAX5, VPREB1, or BTG1), deletions of CDKN2A/B, and mutations in signaling pathways driving proliferation are frequently observed | <1% of childhood B-ALL; rare in adults | TCF3::HLF has a universally dismal prognosis |

| MEF2Drearranged | MEF2D::BCL9 can be detected by FISH. Whole transcriptome or targeted RNA sequencing is more reliable for diagnosis as it detects other MEF2D partners | BCL9 is the most common translocation partner. Others include HNRNPUL1, DAZAP1, CSF1R, SS18, FOXJ2, and DAZAP1 | 4% of childhood and 10% of adult | Unfavorable |

| ZNF384rearranged | FISH, whole transcriptome or targeted RNA sequencing | Numerous partners (EP300, EWSR1, TAF15, TCF3) were reported, either transcription partners or chromatin modifiers. FLT3 overexpression also described | 5% of childhood and 10% of adults B-ALL; 48% MPAL, B/Myeloid | EP300::ZNF384 favorable; TCF3::ZNF384 unfavorable |

| PAX5alt | FISH, whole transcriptome, GEP or targeted RNA sequencing | Numerous fusion partners, copy number alterations are common | 7% | Intermediate for PAX5alt in children and unfavorable in adults |

| PAX5p.P80R | Whole transcriptome or targeted RNA sequencing | PAX5 p.P80R, an inactivating mutation with distinct expression profile, is commonly associated with deletion of alternate allele or copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity | 3% | Favorable in adults; unfavorable in children |

| IG::MYCrearranged | Karyotyping/FISH. Genetic and epigenetic profile distinct from Burkitt lymphoma | Frequent mutations in genes involving RAS pathway, 1q gain | Rare in children; approximately 2% of adult | Unfavorable |

| Complex karyotype (≥5 alterations) | Karyotyping/FISH | TP53 mutations are common | 5% | Unfavorable |

| ETP-ALL | Flow cytometry immunophenotyping | Numerous alterations described. Lower incidence of NOTCH1, FBXW7 mutations than non-ETP-ALL. More frequent mutations in FLT3, DNMT3A, NRAS | 11%–16% of pediatric T-ALL; 7%–17% of adult T-ALL | Unfavorable |

| Disease entity . | Genetic testing . | Additional genetic changes . | Frequency . | Prognostic relevance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypodiploid Near-haploid (24-31 chromosomes) Low-hypodiploid (32-39 chromosomes) High-hypodiploid (40-43 chromosomes) | Karyotyping/FISH | RTK and RAS pathway mutations (NF1), IKZF3 deletion in near-haploid. RB1, CDKN2A/B, IKZF2 deletions, TP53 mutations (up to 50% TP53 mutations are germline) in low-hypodiploidy | Approximately 2% of childhood, rare in adults are near-haploid; approximately 1% of childhood, 10% of adult are low hypodiploid | Unfavorable for near-haploid and low-hypodiploid |

| iAMP21 | FISH for ETV6::RUNX1 used to identify iAMP21 | Defined by 5 copies of RUNX1 per cell, with ≥3 copies on a single abnormal chromosome 21 | 1%–2% in children, rare in adults | Unfavorable; outcomes improve with intensive chemotherapy |

| BCR::ABL1rearranged | Karyotyping/FISH/ PCR/RNA-seq for detection of BCR::ABL1 fusion | IKZF1 deletions (80%) co-occurring with deletions of PAX5 and CDKN2A/B, EBF1 mutations in 14% | 2%–5% in children, 6% in adolescents and young adults, and >25% in adults | Unfavorable; incorporation of TKI targeted therapy has improved outcomes. IKZF1-rearranged unfavorable |

| BCR::ABL1-like (Ph-like) | Whole transcriptome or targeted RNA-seq. When unavailable, derivative methods like TaqMan low-density arrays, multiplex PCR, and FISH panels using break-apart probes may be used | a. ABL-class fusions: Fusions involving ABL1, ABL2, CSF1R, LYN, PDGFRA, PDGFRB b. JAK/STAT abnormalities: These include enhancer hijacking of promoter regions (IGH::CRLF2, P2RY8::CRLF2), fusions and mutations (eg, JAK2 R683G or JAK1 V658F) c. Miscellaneous fusions involving FGFR1, NTRK3, etc. in JAK1/JAK2/JAK3 genes and fusions/truncating deletions of EPOR (eg, EPOR::IGH) frequently associated with IKZF1 deletions and copy number alterations in B-lymphoid transcription factors. Activating mutations involving cytokine receptors (eg, IL7R and CRLF2) also constitute an underlying genetic abnormality | Frequency increases with age: 10%–15% of children, 20%–25% of adult, 50%–60% of patients with Down syndrome | Unfavorable; associated with high minimal residual disease positivity rates. Targeting the underlying genetic abnormality may improve survival rates |

| KMT2Arearranged | Karyotyping/FISH/ Global or targeted RNA sequencing | More than 90 partners of KMT2A described of which AF4, MLLT3, MLLT1, MLLT10, and MLLT6 are common | 70%–85% of infant, 2% of childhood and adult | Unfavorable |

| ETV6::RUNX1-like | Whole transcriptome or targeted RNA sequencing. Increased frequency of ETV6-like B-ALL may be seen in patients with germline ETV6 mutation | Fusions or copy number alterations involving ETV6, ERG, FLI1, IKZF, or TCF3 are common | 3% of childhood, uncommon in adults | Possibly unfavorable |

| TCF3::HLF | Global or targeted RNA sequencing for uncommon partners | Accompanying genetic lesions, including deletion of B-cell differentiation genes (PAX5, VPREB1, or BTG1), deletions of CDKN2A/B, and mutations in signaling pathways driving proliferation are frequently observed | <1% of childhood B-ALL; rare in adults | TCF3::HLF has a universally dismal prognosis |

| MEF2Drearranged | MEF2D::BCL9 can be detected by FISH. Whole transcriptome or targeted RNA sequencing is more reliable for diagnosis as it detects other MEF2D partners | BCL9 is the most common translocation partner. Others include HNRNPUL1, DAZAP1, CSF1R, SS18, FOXJ2, and DAZAP1 | 4% of childhood and 10% of adult | Unfavorable |

| ZNF384rearranged | FISH, whole transcriptome or targeted RNA sequencing | Numerous partners (EP300, EWSR1, TAF15, TCF3) were reported, either transcription partners or chromatin modifiers. FLT3 overexpression also described | 5% of childhood and 10% of adults B-ALL; 48% MPAL, B/Myeloid | EP300::ZNF384 favorable; TCF3::ZNF384 unfavorable |

| PAX5alt | FISH, whole transcriptome, GEP or targeted RNA sequencing | Numerous fusion partners, copy number alterations are common | 7% | Intermediate for PAX5alt in children and unfavorable in adults |

| PAX5p.P80R | Whole transcriptome or targeted RNA sequencing | PAX5 p.P80R, an inactivating mutation with distinct expression profile, is commonly associated with deletion of alternate allele or copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity | 3% | Favorable in adults; unfavorable in children |

| IG::MYCrearranged | Karyotyping/FISH. Genetic and epigenetic profile distinct from Burkitt lymphoma | Frequent mutations in genes involving RAS pathway, 1q gain | Rare in children; approximately 2% of adult | Unfavorable |

| Complex karyotype (≥5 alterations) | Karyotyping/FISH | TP53 mutations are common | 5% | Unfavorable |

| ETP-ALL | Flow cytometry immunophenotyping | Numerous alterations described. Lower incidence of NOTCH1, FBXW7 mutations than non-ETP-ALL. More frequent mutations in FLT3, DNMT3A, NRAS | 11%–16% of pediatric T-ALL; 7%–17% of adult T-ALL | Unfavorable |

Table modified from Choi et al.1

Ph-like ALL

Ph-like ALL, a high-risk subset of Ph-negative B-ALL, shares a gene expression profile with BCR::ABL1-positive ALL yet lacks a BCR::ABL1 gene fusion. Initially observed in children, it is now recognized as high risk in both pediatric and adult populations, affecting approximately 20% to 30% of adults in the United States newly diagnosed with B-ALL.2 Given its chemoresistant nature, patients with Ph-like ALL often undergo allo-HCT due to poor early treatment response. In the GIMEMA LAL1913 trial using a pediatric- oriented protocol in adults, CR rates were lower in patients with Ph-like vs non-Ph-like B-ALL (74.1% vs 91.5%, respectively), with 40% of Ph-like and 11% of non-Ph-like patients undergoing allo-HCT based on MRD.3 Among MRD-positive patients undergoing allo-HCT, no relapses occurred, while 80% of MRD+ Ph-like patients relapsed with chemotherapy alone.

A large single center study found similar outcomes between patients with Ph-like and non-Ph-like ALL undergoing allo-HCT in CR, with Ph-like ALL patients achieving a 3-year overall survival (OS) of 68%.4 Similarly, a South Korean study showed non-inferior outcomes for adults with Ph-like ALL post-transplant compared to standard-risk non-Ph-like ALL, with improved survival compared to high-risk non-Ph-like ALL.5 A single center report from MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) showed favorable outcomes (2-year OS 56%) for patients with CRLF2 overexpressed ALL undergoing allo-HCT6 compared to an earlier study where few received transplant (5-year OS <20%).7 Finally, a recent multicenter analysis of patients with Ph-like ALL undergoing allo-HCT in CR1 (N = 83) demonstrated comparable outcomes to other Ph-negative subtypes.8 In this study, Ph-like ALL patients had higher rates of induction failure but were more likely to achieve MRD negativity with the use of blinatumomab pre-transplant.

Transplant may mitigate relapse risk in Ph-like ALL, but the role of MRD and the differential risk associated with various Ph-like molecular subtypes needs further investigation. While we await further studies, we consider eligible Ph-like ALL patients for allo-HCT in CR1.

Early T-cell precursor ALL

Early T-cell precursor ALL (ETP-ALL) is a subtype of T-ALL with distinct immunophenotype and poor outcomes with conventional chemotherapy in children9 and adults.10 In the NOPHO ALL2008 study of patients (aged 1-45 years) with T-ALL, those with ETP-ALL (N = 37) had inferior early MRD responses, with most subsequently assigned to high-risk chemotherapy or allo-HCT as per protocol.11 Despite initial chemoresistance, relapse risk (RR) and OS were similar in patients with ETP and non-ETP-ALL. Further, an analysis of 47 adult ETP-ALL patients enrolled in the 2003 and 2005 GRAALL (Group for Research on Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) studies demonstrated a survival benefit with allo-HCT in CR1.12 Those with ETP phenotype were not immediately eligible for allo-HCT, yet 49% received allo-HCT related to poor response. Despite early treatment resistance in the ETP cohort, 5-year OS was 60% and not statistically different from other T-ALL subtypes. Although these studies offer indirect evidence supporting the role of allo-HCT in ETP-ALL, the rarity of this disease makes large-scale transplant studies in adult patients unlikely to be undertaken.

KMT2A-rearranged ALL

KMT2A-rearranged (KMT2A-r) B-ALL is a widely recognized high-risk subtype of B-ALL accounting for approximately 5% to 10% of adult ALL cases and involving numerous translocation partner genes.13 MDACC reported outcomes of 50 adult patients with KMT2A-rearranged ALL over three decades, with a 5-year OS of 39% with consolidative allo-HCT post-2010 compared to no survivors beyond 4 years without allo-HCT.14 The benefit of allo-HCT is challenging to discern from clinical trials because nearly all adult protocols rely on consolidation with transplant for KMT2A-r patients. The GRAALL recently published an extensive analysis of 141 adult patients with KMT2A-r ALL treated on their pediatric- inspired protocols.15 Molecular profiling and MRD enabled risk stratification, highlighting worse outcomes for those with additional genetic alterations in TP53, IKZF1, or persistent MRD-positivity by KMT2A genomic fusion assay (gKMT2A). Patients achieving an early MRD-negative CR without high-risk genetics (14/41 with available gKMT2A-MRD) showed a 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse and OS of 7% and 93%, respectively. Notably, one of the included study protocols (GRAALL-2014) did not mandate KMT2A-r patients proceed to transplant if they were MRD negative, and the authors were able to identify a considerable proportion of good responders with excellent outcomes in the absence of transplant (N = 13/14). Extending these findings to less intensively treated patients, older adults, or novel targeted therapies16 requires further validation. Additionally, KMT2A-r leukemias can undergo lineage switching at relapse, leading to dismal outcomes. The increasing use of lineage-specific therapies like CAR-T and blinatumomab in earlier treatment lines may exacerbate this phenomenon.17 Until standardized risk assessment tools are available, we consider consolidative allo-HCT for KMT2A-r patients in CR1.

Ph-positive B-ALL

Treatment of Ph-positive B-ALL in the modern era, given the evolving role of allo-HCT, is discussed in a separate review in this series. In brief, allo-HCT should be considered in patients failing to achieve early molecular responses or those with high-risk features (eg, complex karyotype, IKZF1+). Importantly, long-term data published from the GIMEMA LAL2116, D-ALBA trial18 further demonstrates that even if patients achieve a molecular response following a “chemotherapy-free” induction, HCT consolidation may be omitted for MRD-negative patients; there was a trend toward better disease-free survival in patients who underwent transplants [81.6% (95% CI, 66.7-99.9) vs 69.6% (95% CI, 56.8-85.3)], but survival was similar [80.5% (95% CI, 65-99.9) vs 76.1% (95% CI, 64.3-90.2)]. The excellent long-term outcome for the transplant group enriched for MRD-positive patients (54%) was in part due to a low transplant-related mortality (TRM) rate of just 12.5%, despite the majority of patients (88%) receiving myeloablative conditioning. Less intensive up-front regimens may lower transplant related morbidity and mortality, potentially improving outcomes for subsequent allo-HCT when indicated.

While RT-PCR for BCR::ABL1 is commonly used for MRD detection, next-generation sequencing (NGS)-MRD has emerged as a more sensitive technique,19,20 capable of identifying low-risk patients and those with “CML-like” disease where detectable BCR-ABL1 may not reflect residual ALL.19 In a study of Ph-positive ALL patients with prospectively collected MRD samples, those who achieved NGS-MRD negativity despite being PCR positive (PCR+/NGS−) had no relapses, and those with PCR+/NGS− had similar relapse-free survival and OS to PCR-MRD−/NGS-MRD− patients.19 We assess PCR-MRD and NGS-MRD at regular timepoints throughout frontline treatment and consider allo-HCT for those failing to achieve early milestones. The ideal timing for ultrasensitive NGS-MRD assessment to guide preemptive strategies is uncertain, as is the optimal therapeutic approach for NSG-MRD-positivity (eg, allo-HCT, switching to ponatinib, novel immunotherapies).

TBI- vs non-TBI-based conditioning

Total body irradiation (TBI)-based conditioning regimens have long been standard in patients undergoing allo-HCT for ALL given penetration in sanctuary sites, including the central nervous system, where chemotherapy's efficacy is limited (Figure 1). In pediatric patients, myeloablative TBI-based conditioning is supported by a randomized phase 3 trial showing improved OS and lower relapse rates following TBI (total 12 Gy) plus etoposide compared to chemoconditioning.21 No definitive evidence exists for adults, where there has been interest in avoiding the known toxicities of TBI; however, registry studies and meta-analyses offer insights. A Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research study of ALL patients aged 18-60 years found no OS difference between TBI- and busulfan-based conditioning, though busulfan regimens showed higher relapse rates with lower TRM and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).22 Similarly, an European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) analysis showed comparable OS but higher RR with myeloablative thiotepa compared to TBI-based regimens.23 A meta-analysis of >5000 patients comparing chemotherapy to TBI-based conditioning found TBI regimens improved relapse risk, progression-free survival (PFS), and OS but had higher rates of grade III-IV acute GVHD, with no difference in chronic GVHD or TRM.24 The only randomized trial in adults (median age 26-27, range 14-61) comparing myeloablative TBI-based conditioning to chemotherapy-only for standard-risk B-ALL in CR1 found non-inferior 2-year OS with busulfan and cyclophosphamide (76.6% vs 79.4%), with no differences in NRM or GVHD.25 Notably, the TBI dosage was 9 Gy (2 fractions of 4.5 Gy), differing from the ≥12 Gy typically used in myeloablative allo-HCT for ALL. Taken together, we believe that chemotherapy-only myeloablative conditioning regimens may provide a non-inferior survival for adult patients undergoing transplant, and thus both approaches are reasonable to consider.

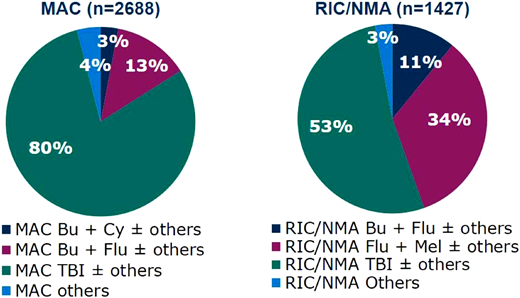

Commonly used myeloablative and reduced intensity conditioning regimens in acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the US, 2019–2022.67 MAC, myeloablative conditioning; RIC/NMA, reduced intensity conditioning/non-myeloablative regimen; Bu, busulfan; Cy, cyclophosphamide; Flu, fludarabine; Mel, melphalan; TBI, total body irradiation.

Commonly used myeloablative and reduced intensity conditioning regimens in acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the US, 2019–2022.67 MAC, myeloablative conditioning; RIC/NMA, reduced intensity conditioning/non-myeloablative regimen; Bu, busulfan; Cy, cyclophosphamide; Flu, fludarabine; Mel, melphalan; TBI, total body irradiation.

Alternative donor allo-HCT in ALL

Optimized GVHD prophylaxis now allows the safe use of alternative donor options, notably haploidentical donors (Figure 2), which considerably increased the donor pool, particularly for racially and ethnically diverse patients who often lack HLA-matched donors.26 A Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research analysis demonstrated that haploidentical allo-HCT with post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) in adults with ALL is associated with similar OS as matched sibling donor (MSD) and matched-unrelated donor (MUD) allo-HCT with less GVHD.27 Furthermore, haploidentical transplant showed superior OS compared to 7/8 MUD and umbilical cord blood allo-HCT due to lower rates of NRM related to less severe acute and chronic GVHD. Further large registry studies supported these findings, demonstrating similar outcomes in ALL patients who received haploidentical transplant with PTCy vs unrelated donor allo-HCT with conventional GVHD prophylaxis.28,29 A prospective genetically randomized trial in MRD-positive patients with ALL demonstrated superior anti-leukemic activity of haploidentical compared to MSD allo-HCT leading to improved OS.30 While these studies precede PTCy's broader application outside of haploidentical allo-HCT, recent EBMT analysis indicates comparable outcomes across haploidentical, MSD, and MUD settings when utilizing PTCy-based prophylaxis in ALL patients in CR1, marked by notably low incidences of acute and chronic extensive GVHD across all donor types.31 Finally, a EBMT analysis done in 2023 found a lower risk of severe chronic GVHD but inferior leukemia free survival with rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) compared to PTCy-based prophylaxis in MUD allo-HCT for ALL in CR1.32 Taken together, haploidentical allo-HCT with PTCy offers a safe and effective approach for ALL patients without matched donors, with outcomes comparable to matched donor transplants, making it the preferred alternative donor option in ALL.

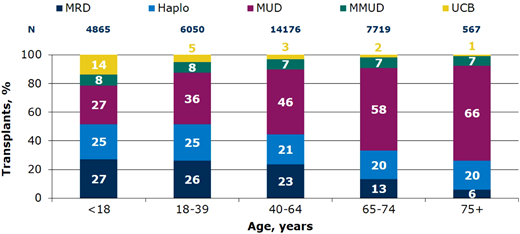

Relative proportion of allo-HCT by donor types in the US by recipient age, 2019-2022.67 Haplo, ≥2 HLA antigen mismatch; MMUD, mismatched unrelated donor ≤7/8 HLA allele match; MRD, matched relate donor; MUD, matched unrelated donor; UCB, umbilical cord blood.

Relative proportion of allo-HCT by donor types in the US by recipient age, 2019-2022.67 Haplo, ≥2 HLA antigen mismatch; MMUD, mismatched unrelated donor ≤7/8 HLA allele match; MRD, matched relate donor; MUD, matched unrelated donor; UCB, umbilical cord blood.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 45-year-old woman is diagnosed with Ph-negative ALL without high-risk features. She undergoes induction with hyper-CVAD and achieves an MRD-negative CR1. She relapses approximately 1 year after diagnosis and receives salvage mini-hyper-CVD, inotuzumab and blinatumomab on trial, achieving an MRD+ CR2, then quickly develops overt relapse. She receives commercial CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy and is now in an MRD-negative CR.

Consolidative vs pre-emptive allo-HCT following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy

CD-19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy effectively induces MRD-negative CR in pediatric and adult patients with relapsed and refractory B-ALL, yet the curative potential of standalone CAR-T in adults with ALL remains uncertain. Our current understanding of preemptive allo-HCT following CAR-T comes from small studies not designed to address the role of transplant consolidation (Table 2). In both the ZUMA-333 and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center trials,34 patients achieving CR after CAR T-cell therapy had similar outcomes regardless of allo-HCT status. Conversely, the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center demonstrated improved event-free survival (EFS) with allo-HCT after CAR-T in adults achieving MRD-negative CR,35 and there were no relapses in the 11 pediatric and AYA patients that underwent consolidative allo-HCT on the ELIANA trial.36 CAR-T product, age, disease risk,37 treatment history including prior allo-HCT,38 and timing of transplant,39,40 among other factors, may account for variability in outcomes across studies.

Characteristics and outcomes across select CD19-directed CAR T-cell trial of adults with B-ALL with consolidative allo-HCT

| Study . | Phase . | Co-stimulatory domain . | N . | Age in years, median (range) . | CR/CRi (%) . | Outcomes (EFS/RFS/LFS/OS) . | Allo-HCT in CR . | Outcomes post-HCT vs no HCT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maude et al., 201862 and Laetsch et al., 202336 NCT02435849 | 2 | 4-1BB | 79 | 11 (3–23) | 82 | 3-year RFS of 44% 3-year OS of 63% | 11 | HCT: 8/8 alive in CR No HCT: not reported |

| Shah et al., 202147 and Shah et al., 202233 NCT02614066 | 2 | CD28 | 55 | 40 (28–52) | 71 | 6-month RFS of 58% Median OS 25.4 months | 10 | HCT: 6/10 alive in CR No HCT: 6/29 alive in CR median DOR unchanged by allo-HCT in sensitivity analysis |

| Shah NN et al., 202163 NCT01593696 | 1 | CD28 | 50 | 14 (4–30) | 62 | Median OS of 10.5 months 6-months EFS of 38% | 21 | HCT: 12/21 alive in CR No HCT: 0/7 alive in CR |

| Park et al., 201834 NCT01044069 | 1 | CD28 | 53 | 44 (23–74) | 83 | Median OS 12.9 months Median EFS 6.1 months | 17 | HCT: 5/17 alive in CR No HCT: 9/26 alive in CR no diff in EFS/OS in MRD- CR |

| Hay et al., 201935 NCT01865617 | 1/2 | 4-1BB | 53 | 39 (20-76) | 85 | Median OS 20 months in responders Median EFS 7.6 months in responders | 18 | HCT: 11/18 alive in CR No HCT: 5/27 alive in CR allo-HCT associated with improved EFS (HR = 0.29) with MRD- CR |

| Frey et al., 202064 NCT01029366 NCT02030847 | 1/2 | 4-1BB | 35 | 34 (21–70) | 69 | Median OS 19.1 months Median EFS 5.6 months | 9 | HCT: not reported No HCT: not reported allo-HCT associated with improved EFS and nonsignificant improved OS |

| Roddie et al., 202165 NCT02935257 | 1 | 4-IBB | 20 | 42 (18–62) | 85 | 2-year OS 58% 2-year EFS 48.3% | 3 | HCT: not reported No HCT: not reported |

| Gu et al., 202066 NCT02975687 | 1 | 4-1BB | 20 | 18 (3–52) | 90 | Median OS 12.9 months Median RFS 6.9 months | 14 | HCT: 7/14 alive in CR No HCT: 0/4 alive in CR |

| Zhang et al., 202037 NCT03173417 | 1/2 | 4-1BB/CD28 | 110 | 12 (2–61) | 93 | 1-year OS 64% 1-year LFS 58% | 75 | HCT: 10/75 relapsed No HCT: 13/27 relapsed allo-HCT associated with improved OS and LFS |

| Study . | Phase . | Co-stimulatory domain . | N . | Age in years, median (range) . | CR/CRi (%) . | Outcomes (EFS/RFS/LFS/OS) . | Allo-HCT in CR . | Outcomes post-HCT vs no HCT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maude et al., 201862 and Laetsch et al., 202336 NCT02435849 | 2 | 4-1BB | 79 | 11 (3–23) | 82 | 3-year RFS of 44% 3-year OS of 63% | 11 | HCT: 8/8 alive in CR No HCT: not reported |

| Shah et al., 202147 and Shah et al., 202233 NCT02614066 | 2 | CD28 | 55 | 40 (28–52) | 71 | 6-month RFS of 58% Median OS 25.4 months | 10 | HCT: 6/10 alive in CR No HCT: 6/29 alive in CR median DOR unchanged by allo-HCT in sensitivity analysis |

| Shah NN et al., 202163 NCT01593696 | 1 | CD28 | 50 | 14 (4–30) | 62 | Median OS of 10.5 months 6-months EFS of 38% | 21 | HCT: 12/21 alive in CR No HCT: 0/7 alive in CR |

| Park et al., 201834 NCT01044069 | 1 | CD28 | 53 | 44 (23–74) | 83 | Median OS 12.9 months Median EFS 6.1 months | 17 | HCT: 5/17 alive in CR No HCT: 9/26 alive in CR no diff in EFS/OS in MRD- CR |

| Hay et al., 201935 NCT01865617 | 1/2 | 4-1BB | 53 | 39 (20-76) | 85 | Median OS 20 months in responders Median EFS 7.6 months in responders | 18 | HCT: 11/18 alive in CR No HCT: 5/27 alive in CR allo-HCT associated with improved EFS (HR = 0.29) with MRD- CR |

| Frey et al., 202064 NCT01029366 NCT02030847 | 1/2 | 4-1BB | 35 | 34 (21–70) | 69 | Median OS 19.1 months Median EFS 5.6 months | 9 | HCT: not reported No HCT: not reported allo-HCT associated with improved EFS and nonsignificant improved OS |

| Roddie et al., 202165 NCT02935257 | 1 | 4-IBB | 20 | 42 (18–62) | 85 | 2-year OS 58% 2-year EFS 48.3% | 3 | HCT: not reported No HCT: not reported |

| Gu et al., 202066 NCT02975687 | 1 | 4-1BB | 20 | 18 (3–52) | 90 | Median OS 12.9 months Median RFS 6.9 months | 14 | HCT: 7/14 alive in CR No HCT: 0/4 alive in CR |

| Zhang et al., 202037 NCT03173417 | 1/2 | 4-1BB/CD28 | 110 | 12 (2–61) | 93 | 1-year OS 64% 1-year LFS 58% | 75 | HCT: 10/75 relapsed No HCT: 13/27 relapsed allo-HCT associated with improved OS and LFS |

Identifying high-risk subsets for relapse post-CAR-T is crucial, with emerging risk factors including disease burden41,42 and prior blinatumomab response,42 while genetic alterations lack clear association with relapse risk.43 Post-CAR T-cell therapy, monitoring for B-cell aplasia (BCA) serves as a marker for functional CAR-T cell persistence, with early loss associated with high relapse rates. However, relying solely on BCA monitoring is insufficient, as CD19-negative relapses occur despite CAR-T persistence.44 Moreover, the predictive value of BCA diminishes over time,44 and the optimal duration of CAR-T persistence remains uncertain. Loss of BCA within ≤6 months from infusion of 4-1BB anti-CD19 CAR T-cell products (eg, tisagenlecleucel) is associated with high relapse rates,44-46 whereas long-term persistence of CD28-containing products (eg, brexucabtagene) may not be necessary for durable remissions.47 Overcoming these limitations, bone marrow NGS-MRD is the most sensitive biomarker for post-CAR-T relapse,44 capable of early detection of both CD19-positive and CD19-negative relapses, thereby enabling timely intervention strategies such as allo-HCT.

In summary, while anti-CD19 CAR-T cells induce deep remissions, many patients experience relapse. Identifying high-risk patients for preemptive allo-HCT remains challenging, necessitating improved risk stratification. Prospective studies are crucial to standardize risk assessment and relapse mitigation post-CAR-T. Until more definitive studies are available, routine MRD (ideally NGS-MRD) monitoring post-CAR T-cell therapy is vital, and we reserve allo-HCT for MRD-positive patients and consider it on a case-by-case basis for patients with high-risk features and those with extensive prior treatment.

Reduced intensity conditioning in allo-HCT for ALL

No prospective randomized trials have directly compared myeloablative conditioning (MAC) to reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens in allo-HCT for ALL. Retrospective registry studies support the efficacy of RIC allo-HCT, showing higher relapse rates but similar survival,48-50 establishing RIC as a therapeutic option for adults ineligible for myeloablative therapy. While the optimal RIC regimen is unknown, an EBMT analysis showed favorable outcomes for RIC allo-HCT in adults aged >45 years, with a 2-year OS of 50% to 60% across commonly used regimens (Flu/Bu, Flu/Mel, or Flu/low-dose TBI)51 and no difference in outcomes between groups. Similarly, thiotepa- and TBI(4-6 Gy)-based regimens are acceptable alternatives to MAC.52

More recently, a registry-based study showed no difference in outcomes when comparing adult patients with ALL who underwent transplants in CR1 following conditioning with fludarabine and either 8-Gy or 12-Gy TBI, despite older age in the 8-Gy cohort (median 56 vs 40 years, respectively).53 Whether these findings apply to patients with higher-risk disease, younger adults, or when TBI is combined with cyclophosphamide is unclear. Finally, in the prospective UKALL14 trial of patients with ALL aged 25-65 years, patients >40 years of age received post-consolidation therapy with fludarabine, melphalan, and alemtuzumab reduced intensity conditioning.54 EFS and OS at four years was 47% and 55%, respectively, with a 4-year cumulative incidence of relapse of 34% and 4-year TRM of 20% in this high risk, older (median age 50) patient population. Though myeloablative regimens are favored in those eligible, RIC remains an effective strategy for select patients to minimize toxicity.

Given the evolving landscape of ALL therapies and increasing use of immunotherapies, several additional factors for allo-HCT may become increasingly relevant. Inotuzumab (InO) carries a veno-occlusive disease (VOD) risk post-allo-HCT,55 necessitating optimized transplant practices in exposed patients.56 Notably, no significant increase in VOD incidence was noted among InO-treated patients at MDACC, likely due to reduced InO dose and fractionation.57,58 Extramedullary failure is a concern with blinatumomab,59 and TBI-based conditioning may be important in mitigating the risk of extramedullary relapse, though this remains speculative. As immunotherapies are used early in treatment, the prognostic value of conventional risk factors will need to be reevaluated. Deep responses from frontline immunotherapies will likely alter the transplant patient population, with more transplants in advanced remission states. Novel approaches to reduced transplant toxicity and mitigate relapse risk, including post-transplant maintenance therapies,60,61 must be studied within shifting transplant demographics and evolving indications. Finally, the feasibility of reducing conditioning intensity and toxicity without impacting relapse rates in patients achieving MRD-negative remissions using ultrasensitive NGS before transplant remains uncertain.

Summary

The decision to transplant a patent with ALL is based on risk stratification and informed by disease phenotype and, importantly, response to treatment (Table 3). With increasingly sensitive MRD testing, it is unclear if genotypic abnormalities will continue to independently influence outcomes or if integrated risk models combining MRD, genetic abnormalities, and clinical variables will outperform any single measure of relapse risk. The necessity of allo-HCT in high-risk genetic anomaly patients achieving early MRD-negative remissions is uncertain, as is the reliability of specific MRD depth or timing in predicting relapse for these individuals. Early referral to a transplant center is essential for personalized and collaborative decision-making in high-risk patients. Effective therapeutics, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitor, have changed the disease trajectory of Ph+ ALL patients, previously considered very high risk, such that these patients no longer warrant transplant for consolidation if induced into molecular remission with induction therapy. Furthermore, active immunotherapies induce greater numbers of relapsed ALL patients into remission, resulting in successful transplants for patients with advanced disease. Finally, improvements in GVHD prophylaxis allow for greater donor availability and access to transplant when indicated.

Summary of recommendations for transplant consolidation in adult ALL

| Indication for transplant* . | |

|---|---|

| *Early referral of high-risk patients for prompt donor search and personalized/collaborative decision-making is critical | |

| Immunophenotype | Early T-cell precursor |

| Karyotype | Complex karyotype; low hypodiploid (32–39 chromosomes); near haploid (24–31 chromosomes) |

| Unfavorable molecular genetic profile | IKZF1; BCR::ABL1-like (Ph-like); KMT2A rearranged; MEF2D rearranged; MYC rearranged; TP53; iAMP21 |

| Slow response to therapy | Time to morphologic CR >4 weeks |

| Persistent MRD post-induction using flow or NGS | |

| No added benefit to transplant consolidation . | |

| BCR::ABL1 rearranged (Ph+) • With incorporation of TKI therapy, studies suggest no benefit to HCT in patients who develop prompt, deep response AND have no evidence for unfavorable molecular features. | |

| Absence of high-risk molecular genetic features AND prompt, deep response to induction therapy. | |

| Role of transplant consolidation not clear . | |

| Consolidation post-CAR-T therapy • Patients with very high risk features and patients with evidence for MRD following CAR-T likely benefit from HCT consolidation; toxicity from extensive prior therapy may result in adverse survival in other patients. | |

| Indication for transplant* . | |

|---|---|

| *Early referral of high-risk patients for prompt donor search and personalized/collaborative decision-making is critical | |

| Immunophenotype | Early T-cell precursor |

| Karyotype | Complex karyotype; low hypodiploid (32–39 chromosomes); near haploid (24–31 chromosomes) |

| Unfavorable molecular genetic profile | IKZF1; BCR::ABL1-like (Ph-like); KMT2A rearranged; MEF2D rearranged; MYC rearranged; TP53; iAMP21 |

| Slow response to therapy | Time to morphologic CR >4 weeks |

| Persistent MRD post-induction using flow or NGS | |

| No added benefit to transplant consolidation . | |

| BCR::ABL1 rearranged (Ph+) • With incorporation of TKI therapy, studies suggest no benefit to HCT in patients who develop prompt, deep response AND have no evidence for unfavorable molecular features. | |

| Absence of high-risk molecular genetic features AND prompt, deep response to induction therapy. | |

| Role of transplant consolidation not clear . | |

| Consolidation post-CAR-T therapy • Patients with very high risk features and patients with evidence for MRD following CAR-T likely benefit from HCT consolidation; toxicity from extensive prior therapy may result in adverse survival in other patients. | |

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Curtis Marcoux: honoraria from Amgen and Kite.

Partow Kebriaei: consultancy from Jazz, Pfizer, and Kite.

Off-label drug use

Curtis Marcoux: None.

Partow Kebriaei: None.