Abstract

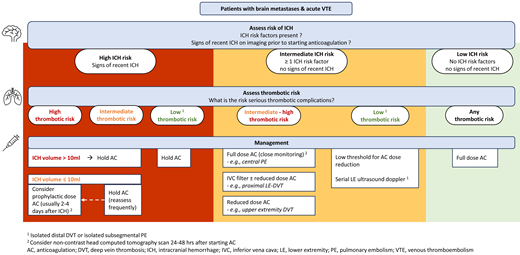

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a prevalent and serious complication among cancer patients, necessitating therapeutic anticoagulation for many individuals with brain metastases. Simultaneously, patients with brain metastases, particularly those with high-risk primary tumors, have an increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). Managing anticoagulation in these patients presents a dual challenge: preventing thromboembolism while avoiding hemorrhagic events. Here, we present our approach to anticoagulation for acute VTE in patients with brain metastases, based on the available evidence. We review potential risk factors for anticoagulation-associated ICH in this population and discuss strategies for managing acute VTE in patients with and without ICH.

Learning Objectives

Understand the incidence and risk factors for ICH in patients with brain metastases

Select the optimal type of anticoagulant in patients with brain metastases and acute VTE

Manage acute VTE in patients with brain metastases and high ICH risk that precludes therapeutic dose anticoagulation

Introduction

Cardiovascular complications are prevalent in cancer patients.1,2 Acute venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a common complication in cancer patients, with an estimated incidence rate of up to 30% in patients with brain metastases, depending on the primary tumor type.1,2 VTE is considered an independent predictor of mortality in this patient population, underlining the necessity to optimize prevention and treatment. The mechanisms driving thrombosis in this population are complex and multifactorial, with involvement of prothrombotic factors from tumor cells, immune system activation, various clinical factors, and anticancer treatments.3-5 Due to the high thrombotic risks, many patients with brain metastases have VTE and thus an indication for therapeutic anticoagulation for at least 3 to 6 months.6,7 Concurrently, spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is a significant and frequent complication in this population, particularly in those with high-risk primary tumors, such as renal cell carcinoma and melanoma.8-10 Of note, the ICH events in these patients are primarily intratumoral.11 Managing anticoagulation in these patients therefore presents a dual challenge: preventing thromboembolism while avoiding hemorrhagic events.

High-quality evidence supports the use of either low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) as anticoagulant therapy for acute VTE in cancer patients.12-17 However, only a minority of patients with known/reported brain metastases were included across the landmark trials.12,13,15-17 While most studies did not exclude patients with known brain metastases, the largest reported number of patients with brain metastases was 29 out of 330 patients in the DOAC arm and 27 out of 308 in the LMWH group of the CANVAS study,17 but major bleeding was not reported in this subgroup. In the HOKUSAI cancer study, major bleeding in patients with brain metastases or primary brain tumors occurred in 2 out of 31 and 4 out of 43 patients in the edoxaban and dalteparin arms, respectively.12 Consequently, the limited existing data on anticoagulation-associated ICH risks and clinical decision-making in this setting stem mainly from small retrospective studies including primarily LMWH-treated patients. Additionally, current leading guidelines on the management of VTE in patients with cancer lack formal evidence-based recommendations in patients with brain tumors.6,7

This review focuses on various aspects in the treatment of acute VTE in patients with brain metastases, exploring the risk factors for anticoagulation-associated ICH and its management. The management of anticoagulation prescribed for atrial fibrillation is beyond the scope of this review.

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 61-year-old woman with no prior medical history presented with dizziness and nausea. She was diagnosed with stage IV non–small cell lung cancer (epidermal growth factor receptor exon 17 deletion) with brain metastases and no evidence of ICH (Figure 1). Osimertinib was initiated as first-line therapy. One week after starting osimertinib, she developed right leg edema. Bilateral lower-extremity venous Doppler confirmed a new right calf DVT. Platelets, renal and hepatic function, partial thromboplastin time, and prothrombin time were normal.

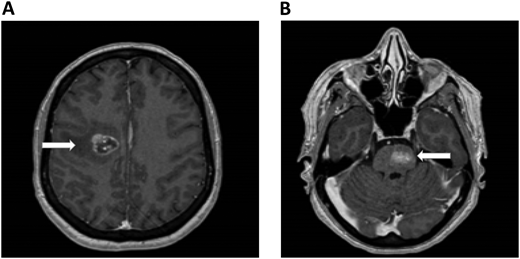

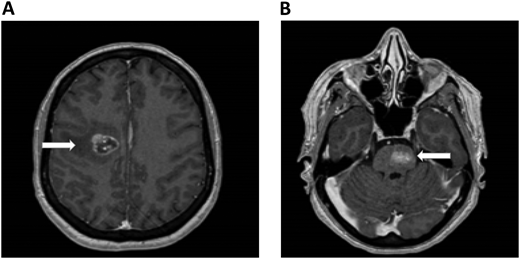

Brain MRI in a patient with non–small cell lung cancer and brain metastases. An axial section of a T1 image with contrast shows right frontal metastases (Panel A) and brain stem metastases (Panel B). The white arrows denote these findings.

Brain MRI in a patient with non–small cell lung cancer and brain metastases. An axial section of a T1 image with contrast shows right frontal metastases (Panel A) and brain stem metastases (Panel B). The white arrows denote these findings.

Hematology was consulted to evaluate whether therapeutic- dose anticoagulation can be given in a patient with newly diagnosed brain metastases. Since her previous brain imaging was 3 weeks earlier, a repeat brain noncontrast CT scan was performed, showing a mild decrease in the size of the brain metastases with no evidence of active bleeding. Her distal DVT was considered to carry a low-intermediate thrombotic risk, potentially enabling reduced-dose anticoagulation if needed. On the other hand, the patient was assessed to have a standard ICH risk, meaning that anticoagulation would likely not lead to a clinically meaningful increase in ICH risk in this setting. Therefore, therapeutic-dose anticoagulation was started with apixaban at 10 mg twice daily for 1 week, followed by 5 mg twice daily. She also continued her anticancer therapy. In this case we did not recommend a routine surveillance brain computed tomography (CT) to assess for ICH after starting anticoagulation.

Anticoagulation in patients with brain metastases

Using anticoagulation in patients with brain metastases presents unique challenges. Acute VTE warrants therapeutic anticoagulation given the associated high mortality rates if left untreated in cancer patients.18 However, ICH is common, complicating patient-tailored decisions on starting anticoagulation, choosing the type of anticoagulation, and deciding on the dose and treatment duration, as well as monitoring for complications. Of note, retrospective cohort studies (and their meta-analyses) have consistently failed to demonstrate a numerical or statistically significant increase in this risk in patients receiving anticoagulation.10Table 1 details the incidence of ICH in patients with brain metastases in meta-analyses of observational studies, without and with different anticoagulants.

Current guidance statements recommend LMWH for patients with brain metastases but suggest that DOACS can be considered.6,7 Several small retrospective studies explored the risk of ICH per type of anticoagulation and indicated DOACs to possibly be a safe alternative to LMWH in this setting.19-21 A recent meta-analysis of the accumulating data confirmed these findings; in 979 patients with brain metastases treated with anticoagulation for the indication VTE or atrial fibrillation, no difference in the risk of ICH associated with the type of anticoagulation was observed (relative risk [RR], 1.05; 95% CI, 0.71-1.56).22 Accordingly, we consider both DOACs and LMWH as acceptable treatment options in patients with brain metastases and acute VTE. We assess relevant drug-drug interactions (ie, carbamazepine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital) and are vigilant of interactions between DOACs and antiseizure medications, which may induce cytochrome P-450 and/or p-glycoprotein, leading to lower DOAC levels. Antiseizure medication such as levetiracetam and lacosamide appear to be acceptable for concurrent use with DOACs.23,24

Risk factors for ICH

No validated ICH risk-assessment models are available to inform the management of patients with brain metastases receiving anticoagulation. We therefore consider the individual risk factors, as detailed below, and recognize that risk factors may be additive or even synergistic. We have focused on cancer-specific risk factors since the vast majority of anticoagulation-associated ICH is intratumoral.21 General risk factors for ICH, such as hypertension, should also be considered and managed (if modifiable) when assessing the risk for ICH, in line with recent guidelines on the management of patients with spontaneous ICH.25

Primary tumor type

The risk of ICH differs greatly between primary tumor types, and renal cell carcinoma and melanoma in particular have consistently been associated with an increased risk of ICH.8,21 The highest rates of ICH, both symptomatic and asymptomatic, have been observed in patients with brain metastases from melanoma (15%-45%),26-28 thyroid cancer (60%),29 and renal cell carcinoma.30,31 The incidence rate of ICH in patients with metastatic brain cancer on anticoagulation is approximately 15% in a meta-analysis of studies with variable follow-up durations, most commonly 6 to 12 months.10 For example, Hamulyák et al reported a 12-month cumulative ICH incidence of 10.1% with DOACs and 12.9% with LMWH treatment.21 Meta-analyses of retrospective data suggest that the risk of ICH is similar whether or not patients are on anticoagulation (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.71-1.56).22 In a matched, retrospective cohort study of 293 patients with brain metastases, the risk of ICH was 4-fold higher in patients with melanoma or renal cell carcinoma (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 3.98; 90% CI, 2.41-6.5) in comparison with lung cancer patients.8 In these patients, the 1-year cumulative incidence of ICH was similar with enoxaparin (35%) and without enoxaparin (34%).8 Importantly, since prospective studies evaluating the risk of ICH in patients with brain metastases are currently lacking, an increased risk associated with anticoagulation cannot be fully ruled out. Nonetheless, since studies using the same methodology have identified a clear increased risk in patients with high-grade glioma and not in those with brain metastases,22,32 we hypothesize that any additive RR risk is likely to be modest. We recognize that in the setting of a high-baseline ICH risk (such as melanoma or renal cell carcinoma), any additional risk factors for bleeding (eg, renal or liver dysfunction, concurrent antiplatelet therapy) may lead to a clinically relevant absolute increase in ICH risk.

Concomitant medication

Antiplatelet agents, including aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors, are frequently prescribed in patients with brain metastases due to coexisting coronary disease, peripheral artery disease, and neurovascular disease.33-35 Although these agents are associated with an increased risk of mainly gastrointestinal bleeding, an association with ICH has not yet been demonstrated in the general population.36 A recent matched cohort study of 392 patients with brain metastases reported a 1-year cumulative incidence of ICH of 22.5% (95% CI, 15.2-29.8) in 134 patients receiving any kind of antiplatelet regimen vs 19.3% (95% CI, 14.1-24.4) in 258 controls receiving no antiplatelet agents.37 In the 31 (23.1%) patients receiving a combination of antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation, the risk of ICH was not increased compared with the use of antiplatelet therapy alone (HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.05-3.25) or no antithrombotic therapy at all (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.34-2.42).37 While these findings are somewhat reassuring, due to the retrospective nature and relatively small sample size of this study caution is warranted with antiplatelet therapy, especially in the presence of other risk factors for bleeding.

Medical anticancer treatment with vascular endothelial growth (VEGF) inhibitors is associated with an increased risk of systemic bleeding and thrombosis.38 Bevacizumab combined with anticoagulation has been associated with an increased risk of ICH in glioblastoma patients,39 but a large meta-analysis did not reveal an increased risk of ICH in patients with breast cancer and brain metastases.38 Given that, even in the absence of anticoagulation, the risk of ICH in patients with brain metastases is high, the use of VEGF inhibitors should be considered in a bleeding-risk evaluation prior to the initiation of anticoagulation.

In addition to the pharmacodynamic interaction attributed to VEGF inhibitors, pharmacokinetic interactions between cytochrome P450 3A4/5 or P-glycoprotein inhibitors with DOACs may theoretically increase the risk of anticoagulation- associated bleeding. In the general population, some studies suggest an increased risk of bleeding with such interactions,40 but the evidence in the context of cancer is limited and pools different drugs as well as pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetics interactions.41,42 Furthermore, whether these interactions increase the risk of clinically relevant bleeding remains debated and likely depends on the individual drug. When the literature and online resources suggest a potential interaction, we consult with a clinical pharmacist/pharmacologist and take additional bleeding-risk factors into account when deciding whether LMWH should be preferred over a DOAC.

Stereotactic radiosurgery

In theory, the treatment of brain metastases with systemic therapy or anatomical therapy such as stereotactic radiosurgery would be expected to decrease the risk of ICH. Some data, however, primarily in patients with melanoma, suggest that there may be a short-term increase in ICH risk after stereotactic radiosurgery in patients with and without anticoagulation.27,28 We recognize that the cohorts are small and that there remains uncertainty regarding this association with conflicting data,43 but generally, consider stereotactic radiosurgery as a possible short-term risk factor for ICH in this setting.

ICH risk factors on brain imaging

A large cross-sectional study of 1030 patients with atrial fibrillation but without brain malignancy reported an association between medium-to-high severity small vessel disease on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and anticoagulation-associated ICH.44 Accordingly, it has been hypothesized that small vessel disease is contributory and possibly causal to anticoagulation-associated ICH. Further evaluation of small vessel disease as a risk factor for ICH in the setting of brain metastases is needed, particularly as anticoagulation is commonly prescribed to these patients, who may have shared risk factors for small vessel disease.

Intratumoral siderosis in brain metastases represents evidence of prior, often subclinical, ICH, but whether this is an independent ICH risk factor remains to be determined. While some studies have supported preexisting intratumoral hemorrhage as a risk factor for recurrent ICH in patients with brain metastases,43,45 the ICH incidence was low in a cohort of patients with brain metastases and intratumoral hemosiderin residues who resumed anticoagulation.46 Among patients with evidence of recent ICH (eg, within 30 days), we generally consider a conservative volume cutoff of more than 10 mL as a potential risk factor for tumor-associated ICH expansion. This is based upon a small retrospective cohort study demonstrating a 14.5% (95% CI, 2.1-38.35) cumulative incidence of recurrent ICH among 16 patients with brain tumors and an ICH volume of more than 10 mL who restarted anticoagulation, compared to 2.6% (95% CI, 0.2%-12.0%) in 38 patients with smaller ICH volumes (including hemosiderin residues alone).46 We routinely review imaging with a neuroradiologist, and information from this review often informs our management decisions.

Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia is a frequently observed complication in cancer patients, either due to the underlying malignancy or induced by anticancer treatment. This is highlighted by a recent cohort study of patients with malignancy and acute VTE that demonstrated a platelet count of less than 100 000/µL in 22% (95% CI, 21%-24%) of patients with a solid malignancy within 2 weeks before or after the VTE and a platelet count of less than 50 000/µL in 7% (95% CI, 6%-8%).47

Full-dose anticoagulation is not recommended in patients with a platelet count of less than 50 000/µL.6,7 A recent post-hoc analysis of the HOKUSAI VTE Cancer study, which included patients treated with anticoagulation for cancer-associated VTE, demonstrated that the risk of bleeding may by increased even at higher platelet counts.48 In this study, patients with platelet counts equal to or lower than 100 000/µL at baseline, 1 month, or 3 months had an increased risk of major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding compared to patients with platelet counts greater than 100 000/µL at these time points.48 In addition, a small prospective cohort study of 134 patients with spontaneous ICH reported mild thrombocytopenia, defined as a platelet count of 100 000 to 150 000/µL, to be a risk factor for hematoma expansion (odds ratio, 8.15; 95% CI, 1.26-52.7).49

CLINICAL CASE 2

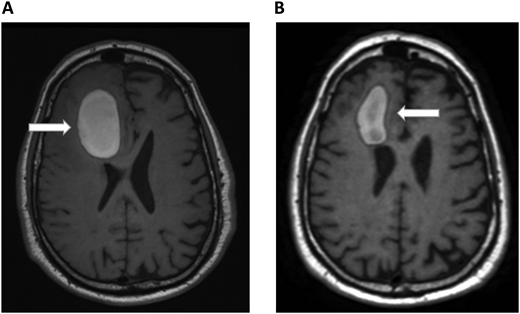

A 72-year-old man with a history of metastatic melanoma presented to the emergency room with new confusion and aphasia. He had been treated with ipilimumab and nivolumab 1 year earlier with complete remission and had known brain metastases treated previously with stereotactic radiosurgery. A brain MRI scan revealed significant frontal intraparenchymal bleeding with surrounding edema, consistent with bleeding brain metastases (Figure 2A). He was admitted to the oncology ward and showed gradual clinical improvement with conservative management. Positron emission tomography CT revealed relapsed systemic disease with liver metastases. Pneumatic graduated compression stockings were used for DVT prophylaxis. On the seventh day of admission, he developed dyspnea. His vital signs were notable for the following: blood pressure, 140/70 mm Hg; pulse, 120 beats/min; respiratory rate, 28 breaths/min; and pulse oximetry, 88% on room air. CT chest PE protocol revealed a new left lobar and segmental pulmonary embolus. His platelets, renal and hepatic function, and partial thromboplastin time and prothrombin time were normal. Echocardiogram did not show right heart strain. Hematology was consulted on the management of a patient with bleeding brain metastases and acute PE. He underwent repeated brain MRI scans that showed improvement in the size of the bleeding and mass effect (Figure 2B). Since the ICH volume was greater than 10 mL, we considered him to be at high risk of ICH expansion and did not consider him to be a candidate for therapeutic-dose anticoagulation in the foreseeable future. We therefore recommended placement of an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter. Because his ICH was 7 days early and was improving clinically and on imaging, we recommended prophylactic-dose enoxaparin. The decision to allow prophylactic-dose anticoagulation is extrapolated from the spontaneous ICH literature that suggests that prophylactic dosing of unfractionated heparin or LMWH can be safely administered within several days of ICH diagnosis.25 For example, retrospective studies demonstrated the safety of initiating LMWH prophylaxis within 48 hours of admission for ICH.49,50 Therefore, when indicated, we consider prophylactic dosing of either unfractionated heparin or LMWH within 2 to 4 days following the diagnosis of ICH. The rationale for prophylactic-dose anticoagulation in this patient is to prevent IVC filter thrombosis and PE progression.

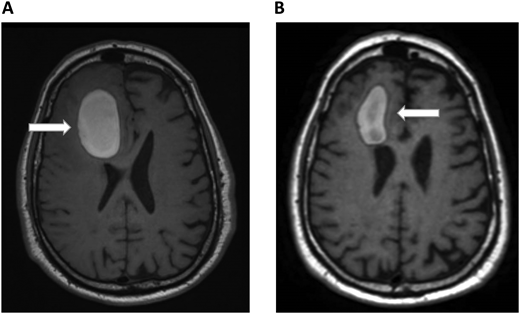

Brain MRI in a patient with melanoma and hemorrhagic brain metastases. In Panel A, an axial section of a T1 image without contrast shows a right frontal hemorrhage (5 cm × 3 cm) with mass effect. In Panel B, a T1 image with contrast demonstrates improvement in the right frontal hemorrhage (3.5 cm × 2 cm) and its mass effect. The white arrows denote these findings.

Brain MRI in a patient with melanoma and hemorrhagic brain metastases. In Panel A, an axial section of a T1 image without contrast shows a right frontal hemorrhage (5 cm × 3 cm) with mass effect. In Panel B, a T1 image with contrast demonstrates improvement in the right frontal hemorrhage (3.5 cm × 2 cm) and its mass effect. The white arrows denote these findings.

Management based on thrombotic risk

When the ICH risk potentially precludes therapeutic-dose anticoagulation in the setting of acute VTE, we adapt our approach according to the risk of thromboembolic complications.

Low-intermediate thrombotic risk

Two well-documented examples of potentially lower-risk VTEs are isolated distal DVT (ie, DVT in the calf veins only, without known radiological evidence of PE) or isolated subsegmental PE (ie, lower-extremity DVT ruled out by screening ultrasound Doppler). In the general population, the rate of extension of an isolated distal DVT in the absence of anticoagulation is between 10% and 20%,51 and anticoagulation primarily reduces recurrent DVT but not PE. Importantly, the relatively favorable outcomes among the general population, even without anticoagulation, may not be generalizable to patients with cancer.52,53

In the RIETE Registry, the rates of recurrent VTE on anticoagulation were similar in cancer patients with isolated distal DVT and proximal DVT.54 However, fatal PE occurred in 19 patients with proximal DVT compared with none in the isolated distal DVT group. While the recurrent VTE risk may nonetheless be similar among cancer patients with proximal DVT and isolated distal DVT,55 the lower risk of PE supports the decision to initially withhold anticoagulation in patients with isolated distal DVT at high ICH risk.

Among patients with isolated subsegmental PE, the risk of recurrent VTE without anticoagulation is fairly modest, with a 90-day cumulative VTE incidence of 3.1% (95% CI, 1.6%-6.1%) in a recent prospective cohort study of 266 patients (without active cancer) not treated with anticoagulation.53 In another observational study of patients with isolated subsegmental PE, including 44% with active cancer, only 1 of 41 patients who did not receive anticoagulation developed recurrent VTE at 1 year.56 We perform baseline and repeat lower-extremity screening ultrasound Doppler in patients with subsegmental PE without known DVT when not receiving full-dose anticoagulation since lower-extremity DVT may be identified in up to 10% of patients within 1 week.57

Taken together, while we generally consider cancer- associated isolated distal DVT, isolated subsegmental PE, and other lower-risk VTEs to have a clinically relevant risk of progression, the sites and nature of recurrence are less commonly life-threatening. On the other hand, the ICH rates are at least comparable in some brain cancer patients and may have serious clinical consequences. Accordingly, we often hold anticoagulation or recommend dose-reduced anticoagulation in patients with brain metastases and higher ICH risk in the setting of acute isolated distal DVT or isolated subsegmental PE but aim to gradually dose escalate anticoagulation if feasible. When anticoagulation is held in this setting, we usually do not place an IVC filter and use surveillance lower-extremity ultrasound dopplers to assess for proximal DVT.

Standard/high thrombotic risk

In patients with acute VTE and an absolute contraindication for therapeutic anticoagulation, placement of an IVC filter is a potential therapeutic option. Both the safety and efficacy of IVC filters in patients with cancer are an ongoing topic of debate, consequently leading to variation in clinical practice. A recent population-based cohort study of 88 585 patients with cancer, acute lower-extremity DVT, and bleeding-risk factors (such as upper gastrointestinal bleeding, ICH, coagulopathy) reported a significant improvement of PE-free survival in patients who had IVC filter placement compared to those who did not (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.64-0.75).58 In the subgroup of patients with brain cancer, brain metastases were not separately defined, and the rate of PE in 1450 patients with IVC filters was 4.3%, compared to 5.6% in 3071 patients without IVC filters.58 A matched cohort analysis of cancer patients with PE and/or lower-extremity DVT enrolled in the RIETE Registry compared the rates of PE-related mortality between those with IVC filter placement due to contraindications for anticoagulation and those without IVC filters. In the matched subgroups of patients with PE with or without lower-extremity DVT, IVC filter placement was associated with a lower PE-related mortality rate (0.7% vs 4.9%; odds ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.02-1.13; P = .07). Among patients with PE and IVC filter placement in this study, only 50 out of 156 (32%) had signs of lower-extremity DVT and 41 had proven DVT. Extrapolating from the above, we consider placement of an IVC filter a reasonable option in patients with brain metastases and acute proximal lower-extremity DVT or PE with or without concomitant lower-extremity DVT (excluding isolated subsegmental PE) who have a very high risk of anticoagulation-associated ICH or recent ICH precluding full-dose anticoagulation.59

Management and outcomes of anticoagulant-associated ICH

The overall outcomes associated with anticoagulation- related ICH appear poor, characterized by high rates of recurrent thrombosis and mortality, which is mostly cancer related and not due to fatal ICH.21,46 In patients with ICH (not including hemosiderin residues), management typically involves holding anticoagulation therapy. In a recent large cohort study including 505 patients with brain metastases, most patients with ICH (including some with hemosiderin residues only) continued or resumed anticoagulation after ICH.21 In 19 of 42 patients who had anticoagulation-associated ICH, anticoagulation was continued immediately after the occurrence of ICH. In the 23 of 42 patients in whom anticoagulation was initially held, the majority had a mild clinical presentation and resumed anticoagulation within 90 days of the ICH event.21 Another study involving 79 patients with primary brain tumors and brain metastases reported a 14.5% (95% CI, 2.1%-38.35%) 1-year cumulative incidence of recurrent ICH after reintroduction of anticoagulation in 16 out of 31 patients with initial major ICH (defined as an ICH >10 mL in size, causing symptoms or requiring intervention).46 In this study, the recurrent ICH incidence at 1 year was much lower in 38 out of 48 patients with a smaller (ie, trace or measurable) initial ICH (2.6%; 95% CI, 0.2%-12.0%).

The difference in recurrent ICH between these cohorts may be related to patient characteristics and/or management and emphasizes the need for case-by-case management. These data also suggest that ICH size and clinical presentation may be associated with the risk of recurrent ICH. Our default is to hold anticoagulation while assessing the ICH-specific and general bleeding-risk factors, balanced against the risk of recurrent thrombosis, and taking the prognosis and goals of care into account. We then decide whether, how, and when to continue anticoagulation.

Knowledge gaps

Future studies should aim to develop predictive models for ICH, incorporating factors such as primary tumor type, concomitant medications, and a previous history of ICH. Additionally, evidence is needed on the use of reversal agents and the optimal timing for resumption of anticoagulation in this setting, and their association with patient outcomes. There is also a need for prospective data on the use of DOACs in this setting. These efforts could lead to more tailored and effective management strategies for anticoagulation in patients with brain metastases, ultimately improving their prognosis and quality of life.

Conclusions

Spontaneous ICH is a critical concern for patients with brain metastases requiring anticoagulation. Despite the complexities and risks associated with anticoagulation therapy, recent studies suggest that DOACs may offer a safety profile comparable to LMWH. Individualized treatment plans, considering patient-specific risk factors, are essential to optimize outcomes. Future research should focus on developing predictive models for ICH and refining management guidelines to better address the needs of this vulnerable population. By advancing our understanding of the interplay between anticoagulation and hemorrhage, we can improve patient care and outcomes in this challenging clinical scenario.

Acknowledgments

Avi Leader is part funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Eva. N. Hamulyák: no competing financial interests to declare.

Shlomit Yust-Katz: no competing financial interests to declare.

Avi Leader: honoraria: Leo-Pharma.

Off-label drug use

Eva. N. Hamulyák: No off-label drug use to disclose.

Shlomit Yust-Katz: No off-label drug use to disclose.

Avi Leader: No off-label drug use to disclose.