Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a significant public health concern in sub-Saharan Africa, where it is the most prevalent genetic disorder, presenting numerous health care and sociocultural challenges. A case study of a young girl from Ghana's Ashanti region illustrates the stigma surrounding SCD, driven by traditional beliefs and misconceptions that perceive SCD as a spiritual affliction. This stigma results in social ostracism and discrimination, impacting affected individuals and their families. Despite the severe and unpredictable pain associated with SCD, effective management is often hampered by limited health care resources and infrastructure. In Ghana and other African countries, inadequate pain relief and a lack of specialized care worsen the suffering of people with SCD. Health care providers' responses vary from empathy to dismissal, reflecting broader systemic issues in care delivery. Stigma has extensive effects, including social exclusion, psychological distress, and educational setbacks. The case study underscores the vital role of community education and support networks, such as those provided by the Sickle Cell Foundation of Ghana and Sickle Cell Association of Ghana, in reducing humiliation and enhancing the lives of those affected by SCD. Addressing the complex challenges of SCD in Africa requires comprehensive strategies. Improving the health care infrastructure, promoting community education, and establishing robust support systems are crucial to alleviating the burden of SCD, with the involvement of both government and nongovernmental organizations. These measures help create a more inclusive and understanding environment for individuals living with this chronic condition, enhancing their quality of life and overall well-being.

Learning Objectives

Identify the cultural beliefs and misconceptions contributing to the stigma associated with sickle cell disease and pain

Understand the psychosocial impact of sickle cell disease on patients and families, including social exclusion and emotional distress

Introduction

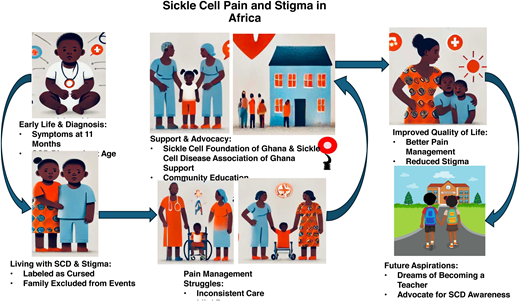

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most prevalent genetic disorder worldwide. Recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations, it stands as a significant public health challenge in sub-Saharan Africa.1,2 Approximately 75% of the 305 000 annual global SCD births occur in this region.3 SCD poses a critical health burden, impacting both mortality and morbidity. Clinical symptoms of SCD include anemia, infections, and complications from vaso-occlusion (blood vessel blockage) and hemolysis. Vaso-occlusion restricts the oxygen supply to tissues, causing acute painful episodes, a key feature of SCD. Furthermore, both vaso-occlusion and hemolysis can lead to other complications, such as stroke, acute chest syndrome, priapism, leg ulcers, and chronic organ failure. Notably, sickle cell pain is deeply ingrained in certain cultures in Africa; for instance, among the Twi-speaking people in Ghana it is referred to as “Ahututuo” (body pinching).4 Beyond physical health, SCD exerts a significant psychosocial impact due to daily symptoms, pain, chronic complications, and societal attitudes toward affected individuals (Figure 1). The term “stigma” originated in ancient Greece, where it referred to symbols burned or tattooed into the skin to identify criminals, slaves, or traitors.5 Social stigma manifests as strong disapproval of a person or group based on perceived characteristics that set them apart from societal and cultural norms. In Africa, cultural factors intersect with SCD- related beliefs and practices, leading to feelings of shame and guilt among those affected.6-9

Case study: a child with sickle cell disease

Early life and diagnosis

A girl was born into a close-knit community in a rural village in the Ashanti region of Ghana. Her parents were farmers with limited formal education. She was their third child, and unlike her older siblings, she exhibited signs of illness from a young age. The onset of symptoms was noticeable from around 11 months of age, when she began experiencing frequent bouts of fever and unexplained pain. At the age of 2, she experienced painful swelling in her hands and feet, which puzzled her parents. Feeling concerned, her parents took her to the nearest community health post, from where she was then referred to the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi. The child was eventually diagnosed with SCD and enrolled in the sickle cell clinic. This diagnosis was met with confusion and fear as her parents had never heard of SCD. Nonetheless, when an experienced pediatrician at the sickle cell clinic explained in the local language, Twi, that this was “Ahotutuo,” her parents remarked that this illness is attributed to spiritual causes and divine retribution.

Living with SCD and early stigma

As this child grew older, the community's reaction to her condition became more pronounced. Traditional beliefs and misconceptions about SCD led to her being labeled as cursed or bewitched. Neighbors whispered that her family must have offended the spirits, leading to her suffering. Social stigma affected her entire family, often leading to their exclusion from social events and community activities. Despite these challenges, her parents were committed to giving her a normal life. They made sure she attended school and did their best to protect her from harsh comments and social ostracism. Nevertheless, her frequent absences due to pain crises and hospital visits made it difficult for her to keep up with her peers academically. On average, she missed school about once or twice a week due to her condition.

Pain-management struggles

The child's pain crises were unpredictable and excruciating. The local health post had limited resources and often only provided basic pain relief like paracetamol, which was insufficient for her severe pain. During more intense episodes, she had to be transported to the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, a 300-mile journey that was both physically taxing due to poor road conditions and financially burdensome for her family. These severe pain episodes occurred about once a month. At the hospital her experiences varied. Some doctors and nurses were compassionate and did their best to manage her pain within the constraints of available resources. Others, however, were dismissive, attributing her pain to psychological factors or accusing her of exaggerating her symptoms (Table 1). This inconsistent care further contributed to her anxiety and feelings of hopelessness.

Case study summary of a young girl with SCD from Ghana

| Aspect . | Details . |

|---|---|

| Early life and diagnosis | Diagnosed at age 2; frequent fevers, pain, and swelling; family unaware of SCD |

| Stigma and community reaction | Viewed as cursed or bewitched; family faced social exclusion and whispers in the community |

| Pain management struggles | Basic pain relief (paracetamol) often insufficient; mixed responses from health care providers |

| Social and educational impact | Bullying and isolation in school; academic performance affected; found solace in reading |

| Psychological impact | Feelings of worthlessness and depression; parents felt guilt and emotional strain |

| Support and advocacy | Received support from SCFG and SCD Association of Ghana; improved community attitudes |

| Future aspirations | Determined to become a teacher; inspired to advocate for inclusive environments for children with SCD |

| Aspect . | Details . |

|---|---|

| Early life and diagnosis | Diagnosed at age 2; frequent fevers, pain, and swelling; family unaware of SCD |

| Stigma and community reaction | Viewed as cursed or bewitched; family faced social exclusion and whispers in the community |

| Pain management struggles | Basic pain relief (paracetamol) often insufficient; mixed responses from health care providers |

| Social and educational impact | Bullying and isolation in school; academic performance affected; found solace in reading |

| Psychological impact | Feelings of worthlessness and depression; parents felt guilt and emotional strain |

| Support and advocacy | Received support from SCFG and SCD Association of Ghana; improved community attitudes |

| Future aspirations | Determined to become a teacher; inspired to advocate for inclusive environments for children with SCD |

Support and advocacy

A turning point occurred when the child and her family met staff from the Sickle Cell Foundation of Ghana (SCFG) at the sickle cell clinic in the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital. SCFG, dedicated to newborn screening, SCD awareness, and training, organized community education sessions to dispel myths about SCD and provide accurate information. It also trained community nurses in effective pain-management techniques and provided resources for better care. Through SCFG, the family received counseling and support. They were also introduced to the Sickle Cell Association of Ghana, a patient and caregiver support group. For the first time, the child met other children with SCD, which helped her feel less isolated. Additionally, this allowed her parents to share their experiences and learn from others facing similar challenges.

Improved pain management and quality of life

The child's pain management improved significantly. She received better analgesia, including a combination of paracetamol, stronger medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and occasionally opioids at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital when necessary. Her parents were educated on how to manage her condition at home. Regular checkups and a more supportive health care environment made a noticeable difference in her overall health and psychological well-being. Additionally, nonpharmacologic interventions such as warm baths and relaxation techniques were introduced.

The community's attitude toward the family also began to change with improved knowledge and understanding about SCD, and the stigma gradually decreased. The child‘s peers started including her in activities, and her teachers, now better educated about SCD, provided her with the support she needed to catch up academically. Her teachers received education through workshops conducted by health care professionals from the SCFG.

Future aspirations

This child became more hopeful about her future. She continued to face challenges; however, with family support, SCFG, and a more informed community, she was better equipped to manage her condition. She remained determined to become a teacher and advocate for children with SCD, aiming to create a more inclusive and compassionate environment for future generations.

Discussion

SCD is a major public health concern in Africa and is especially prevalent in the sub-Saharan regions, where it occurs at the highest rates worldwide. The case study of a young girl from Ghana's Ashanti region offers valuable insights into the broader challenges related to SCD in Africa, including health care accessibility, cultural beliefs, and societal impacts. Addressing these complex and interrelated issues is essential for enhancing the quality of life for those affected by SCD across the continent.

Pain management in SCD

Pain is the most common and debilitating symptom of SCD, often described as unpredictable and severe. In many African settings, the management of SCD pain is hampered by limited resources and an inadequate health care infrastructure. Similar to the child's experience in Ghana, other African countries face significant challenges in managing SCD pain due to resource constraints (Table 2). For example, in Mali and Nigeria many patients with SCD do not receive adequate pain relief during crises due to the unavailability of analgesics for severe pain and trained health care professionals.10,11 Moreover, pain management for children frequently deviates from WHO guidelines. These guidelines recommend a stepwise approach, beginning with nonopioid analgesics such as paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and escalating to opioids for severe pain. Unfortunately, reliance on over-the-counter medications often proves inadequate for severe pain management. Additionally, health professionals' reluctance to prescribe opioids due to addiction concerns exacerbates the situation, leading to unused opioid stocks in many African countries.

Summary of stigma and pain-management issues in SCD across African countries

| Country . | Stigma-related beliefs . | Pain-management challenges . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana | Illness attributed to spiritual causes; social ostracism | Limited access to opioids; inconsistent provider attitudes | Manuscript case study; Dennis-Antwi et al7 |

| Nigeria | SCD perceived as a curse or ancestral sin | Rural areas lack access to specialized care | Oshikoya et al11 Munung et al14 |

| Mali | SCD sometimes viewed as a supernatural condition | Inadequate availability of strong analgesics | Diallo et al10 |

| Kenya | SCD seen as a maternal inheritance only | Children not treated adequately | Marsh et al9 |

| Cameroon | SCD attributed to breaking taboos or spiritual punishment | Lack of trained health care professionals | Munung et al14 |

| Country . | Stigma-related beliefs . | Pain-management challenges . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana | Illness attributed to spiritual causes; social ostracism | Limited access to opioids; inconsistent provider attitudes | Manuscript case study; Dennis-Antwi et al7 |

| Nigeria | SCD perceived as a curse or ancestral sin | Rural areas lack access to specialized care | Oshikoya et al11 Munung et al14 |

| Mali | SCD sometimes viewed as a supernatural condition | Inadequate availability of strong analgesics | Diallo et al10 |

| Kenya | SCD seen as a maternal inheritance only | Children not treated adequately | Marsh et al9 |

| Cameroon | SCD attributed to breaking taboos or spiritual punishment | Lack of trained health care professionals | Munung et al14 |

Access to specialized care

The geographical and infrastructural barriers also play a critical role in pain management. In African countries such as Ghana, Nigeria, and Tanzania, a significant proportion of patients with SCD live in rural areas with limited access to tertiary health care facilities equipped to handle complex SCD cases.12 The financial burden and physical strain of such journeys further complicate access to timely and adequate pain management.

Disparities in health care provider attitudes

Health care provider attitudes toward SCD pain can also vary significantly. In some instances, as seen in the Ghanaian case, there is a tendency among health care workers to underestimate the pain or attribute it to psychological factors. Qualitative research in Ghana, Nigeria, and Tanzania revealed that patients with SCD often encounter skepticism from health care providers regarding the severity of their pain, leading to inadequate pain management and increased patient frustration.12 Concerns about potential addiction and misuse often lead to cautious prescribing practices. This cautious approach can sometimes result in inadequate pain management for patients who truly need these medications. Health care professionals often lack training in SCD management and are sometimes dismissive of patients' pain, attributing it to psychological issues rather than recognizing it as a symptom of a chronic condition.13 This is similar to the mixed responses from health care staff described in the case study from Ghana.

Stigma, misconceptions, and traditional beliefs

In many African regions, SCD is often misunderstood and surrounded by myths. For instance, a study across Cameroon, Ghana, and Tanzania revealed that some perceive SCD as a supernatural condition, resulting in stigma and social exclusion.14 Traditional beliefs often attribute SCD to spiritual retribution or curses. Unfortunately, these beliefs result in stigma and discrimination against affected families. Families therefore attribute SCD to a consequence of breaking taboos or divine retribution.14,15 These misconceptions contribute to stigma and social isolation, adversely affecting the quality of life for individuals with SCD and their families (Table 3). Nevertheless, these same beliefs also offer coping mechanisms through rituals and prayers aimed at appeasing spirits or seeking healing. Churches provide emotional and social support to SCD-affected families, including prayers, counseling, and material aid. Their teachings on compassion and communal solidarity help mitigate SCD-related stigma by emphasizing care and empathy. Similarly, mosques play a supportive role, drawing from Islamic teachings on caring for the sick to reduce stigma and offer practical assistance. Regular prayers and guidance from imams strengthen families as they navigate the challenges posed by SCD.

Survey results on perceptions of SCD and stigma in health care providers and community members

| Country . | Respondent group . | Key perceptions and beliefs about SCD . | Stigma level . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana | Health care providers | SCD seen as a manageable condition; mixed attitudes toward pain | Moderate | Dennis-Antwi et al7; manuscript case study |

| Community members | SCD often viewed as a spiritual affliction | High | Anie et al12; manuscript case study | |

| Nigeria | Health care providers | Varied understanding of SCD; some skepticism about pain reports | Moderate to high | Adigwe et al13 |

| Community members | SCD perceived as a curse or result of ancestral sins | High | Anie et al12; Munung et al14 | |

| Mali | Health care providers | Basic understanding of SCD; limited resources for pain management | Low to moderate | Diallo et al10 |

| Congo | Community members | SCD seen as supernatural; leads to social exclusion | High | Lelo et al16 |

| Tanzania | Health care providers | Acknowledgment of SCD's impact but skepticism | Moderate | Munung et al14 |

| Community members | Misconceptions about SCD origins; stigma prevalent | High | Anie et al12; Munung et al14 2024 | |

| Cameroon | Health care providers | Recognition of SCD challenges but limited training | Moderate | Munung et al14 |

| Community members | Beliefs linking SCD to breaking taboos | High | Munung et al14 |

| Country . | Respondent group . | Key perceptions and beliefs about SCD . | Stigma level . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana | Health care providers | SCD seen as a manageable condition; mixed attitudes toward pain | Moderate | Dennis-Antwi et al7; manuscript case study |

| Community members | SCD often viewed as a spiritual affliction | High | Anie et al12; manuscript case study | |

| Nigeria | Health care providers | Varied understanding of SCD; some skepticism about pain reports | Moderate to high | Adigwe et al13 |

| Community members | SCD perceived as a curse or result of ancestral sins | High | Anie et al12; Munung et al14 | |

| Mali | Health care providers | Basic understanding of SCD; limited resources for pain management | Low to moderate | Diallo et al10 |

| Congo | Community members | SCD seen as supernatural; leads to social exclusion | High | Lelo et al16 |

| Tanzania | Health care providers | Acknowledgment of SCD's impact but skepticism | Moderate | Munung et al14 |

| Community members | Misconceptions about SCD origins; stigma prevalent | High | Anie et al12; Munung et al14 2024 | |

| Cameroon | Health care providers | Recognition of SCD challenges but limited training | Moderate | Munung et al14 |

| Community members | Beliefs linking SCD to breaking taboos | High | Munung et al14 |

Social exclusion and discrimination

Stigma can have profound effects on social interactions. Most participants and caregivers in a study in the Congo expressed that society holds negative perceptions, attitudes, and limited knowledge about SCD. Children with SCD often experience marginalization, exclusion, and neglect within both society and educational settings. They encounter various challenges related to health care, disease management, financial constraints, and a lack of psychological support.16 Another study in Ghana revealed that SCD-related stigma in young people is marked by prejudice, negative labeling, and social discrimination.17

Family dynamics and emotional burden

Stigma and misconceptions surrounding SCD also place a significant emotional burden on families. In Ghana's Ashanti region and elsewhere in Africa, these misconceptions lead to mothers unfairly bearing blame. Communities view the mother (as the child-bearer) as having offended spirits or brought a curse upon the family due to the child's condition. Consequently, emotional stress weighs heavily on these mothers, who not only care for their sick children but also endure social ostracism and stigma. Additionally, mothers especially feel guilt over their child's suffering, believing they are solely responsible because SCD inheritance is only maternal. The financial strain of ongoing medical care, coupled with limited health care access, exacerbates feelings of helplessness.

In Kenya, research has shown that mothers of children with SCD are often subjected to blame within their families and social isolation, contributing to feelings of loneliness together with their children.9 This resonates with the case study, in which the parents felt guilt and helplessness, exacerbating family tensions and emotional stress.

Community education and awareness

Educational initiatives are essential for dispelling myths and reducing the stigma around SCD. Efforts by organizations like the SCFG to educate communities about SCD are vital. In many countries in Africa, similar initiatives have shown success in changing community perceptions and improving support for affected individuals.13 These programs often involve collaboration with local leaders and use culturally relevant materials to effectively reach diverse audiences.18-20

Improving health care and pain management

Improving SCD management requires investment in health care infrastructure, especially in rural areas. In Ghana, the Community-Based Health Planning and Services program established in 1999 provides doorstep health care to rural communities, focusing on women and children. The program aims to reduce health disparities and has become Ghana's primary strategy for close-to-client health care delivery, resulting in positive health outcomes.21 In Africa, expanding specialized care through mobile clinics and telemedicine can further bridge the gap for rural communities.

Training and capacity building

Training programs for health care providers on the specifics of SCD and its management are critical. Health care provider training is essential to ensure effective SCD management. In Ghana, several initiatives have bolstered the capacity of health care professionals to manage SCD. Notably, SCFG established the GENECIS Short Course in Genetic Education and Counseling, specifically tailored for health professionals.19,20 This program was later expanded by the West African Genetic Medicine Centre at the University of Ghana and accredited. Additionally, the center introduced a groundbreaking Master of Science in Genetic Counseling program. Collaborations between Nationwide Medical Insurance (a Ghanaian private commercial health insurance company) and Novartis resulted in virtual Continous Professional Development-accredited training for approximately 300 health care professionals. This training focused on preventing and managing vaso-occlusive crises in SCD. Scaling up such training initiatives across Africa holds promise for standardizing care and improving outcomes for patients with SCD.

Clinical trials and disease-modifying therapy

Clinical trials and disease-modifying therapies are vital for advancing SCD treatment. These trials provide crucial data on new treatments' safety and efficacy, improving patient outcomes. Nonetheless, acceptance varies among individuals with SCD, health care providers, caregivers, and society. In many African countries, skepticism persists due to historical mistrust and a lack of understanding. Educating patients and communities about the benefits and safety of clinical trials can enhance participation and trust. Health care providers play a key role in advocating for these trials but often need more training and resources.

Role of African governments and nongovernmental organizations

African governments should develop policies prioritizing SCD newborn screening, diagnosis, and treatment with funding. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) can advocate for policy changes and collaborate with governments. Both entities can play a crucial role in improving health care infrastructure, raising awareness, and ensuring equitable access to care. Furthermore, governments should allocate funding for SCD research while NGOs provide patient support and advocate for patients' rights. Collaborative efforts can address SCD disparities and make a significant impact across the continent. Recently, WHO in the African Region has released guidance to strengthen SCD efforts. The WHO Sickle Package of Interventions for Sickle Cell Disease Management provides comprehensive strategies for managing SCD, tailored to the African context.22

Conclusion

Improving the lives of those affected by SCD in Africa requires addressing health care infrastructure, affordable treatment, cultural beliefs, and social stigma alongside ongoing community education, health care development, and support networks, with crucial roles played by governments, NGOs, and international societies in fostering acceptance and advancing SCD management.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to the family who permitted me to study their case and all other families affected by sickle cell disease at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi, Ghana. I am deeply thankful for my involvement with the Sickle Cell Foundation of Ghana and leadership of the late Kwaku Ohene-Frempong, along with my continued engagement with the Sickle Cell Association of Ghana.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Kofi A. Anie: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Kofi A. Anie: Nothing to disclose.