Abstract

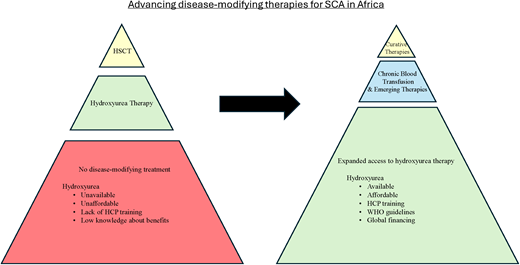

The mortality burden of sickle cell anemia (SCA) is centered in sub-Saharan Africa. In addition to a lack of systematic programs for early diagnosis, access to disease-modifying treatments is limited to only a few urban centers. Providing a safe and adequate blood supply is a major challenge, heightening mortality from SCA-associated complications that require urgent blood transfusion and making the delivery of regular transfusion therapy for stroke prevention nonfeasible. Hydroxyurea therapy with proven clinical benefits for pain episodes, acute chest syndrome, malaria, transfusions, hospitalizations, and stroke prevention is the most feasible treatment for SCA in Africa. Access barriers to hydroxyurea treatment include poor availability, unaffordable costs, health professionals' reluctance to prescribe, a lack of national guidelines, and exaggerated fears about drug toxicities. Strategies for the local manufacture of hydroxyurea combined with the systematic education and training of health professionals using guidelines supported by the World Health Organization can help surmount the access barriers. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as a curative therapy is available in only 7 countries in Africa. The few patients who have suitable sibling donors and can afford a transplant must usually travel out of the country for treatment, returning to their home countries where expertise and resources for posttransplant follow-up are lacking. The recently developed ex-vivo gene therapies are heavily dependent on technical infrastructure to deliver, a daunting challenge for Africa. Future in-vivo gene therapies that bypass myeloablation and ex-vivo processing would be more suitable. However, enthusiasm for pursuing these gene therapies should not overlook strategies to make hydroxyurea universally accessible in Africa.

Learning Objectives

Compare the current state of therapies for SCA in Africa with high-income countries

Identify access barriers to disease-modifying and curative treatments for SCA

Apply concepts of practice and systems innovation to recommend strategies to improve clinical outcomes of SCA in Africa

CLINICAL CASE

An 11-year-old girl with sickle cell anemia (SCA [HbSS]) presented to a busy sickle cell clinic with complaints of limping for about 2 weeks. She was diagnosed with SCA at the age of 2 years when hospitalized with malaria-associated severe anemia requiring blood transfusion. An examination at this clinic visit revealed right hemiparesis consistent with stroke. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was not available, and her family could not afford to obtain one at a distant private hospital. The doctors recommended initiating blood transfusion therapy to prevent the recurrence of stroke.

Introduction

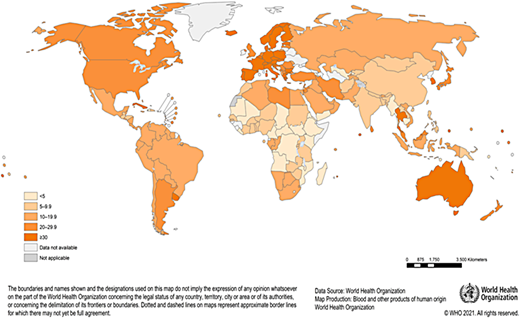

The provision of a safe and adequate blood supply in Africa is a major challenge. Blood safety is hampered by limited resources, the high prevalence of transfusion-transmissible infections (HIV, hepatitis B, and malaria), and an overreliance on family replacement blood donors. Donor recruitment and retention are negatively affected by high donor deferrals, limiting the capacity of blood services to meet demands.1,2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), most countries in Africa fall below the minimum 10 donations per 1000 population needed to meet blood transfusion requirements in their countries (Figure 1). Recent data show that the gap between the need and supply of blood in Africa is large and that the WHO minimum target is an underestimate for many countries.3,4 Children with malaria, children and adults with SCA, women experiencing postpartum bleeding, and individuals experiencing traumatic injuries, often in urgent need of blood transfusions, have a heightened mortality risk.

Blood transfusions for treatment of SCA in Africa

In Africa, blood transfusion in patients with SCA is commonly episodic and used to manage acute complications.5 These include malaria-associated severe anemia, acute splenic sequestration, acute chest syndrome, sepsis, acute stroke, and multiorgan failure. The combination of poor access to disease-modifying treatments and an inadequate blood supply to manage acute complications accounts for SCA's high contribution to total mortality at all ages.6

Chronic monthly blood transfusion therapy in Africa is even more challenging. In addition to inadequate supply, risks from transfusion-transmitted infections, iron overload, alloimmunization, and transfusion reactions is the extremely high burden to patients and their families from monthly visits, intravenous access issues, iron chelation therapy, and prohibitive costs overall. Thus, chronic blood transfusion therapy is currently not feasible as a disease-modifying treatment for SCA in most parts of Africa.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

Three months into a monthly blood transfusion schedule, the decision was made to switch to hydroxyurea treatment due to challenges with blood availability and the prohibitive financial burden to the family. Hydroxyurea was commenced at a dose of 19.5 mg/kg/d and escalated to 26.5 mg/kg/d maximum tolerated dose (MTD) over 4 months.

A complete blood count (CBC) and differential were done at commencement, month 2 (before the first dose escalation), month 4 (before the second escalation), and every 3 months after MTD was achieved, targeting an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 2 to 4 × 109/L. Doses were escalated by 2.5 to 5 mg/kg. Seven months into treatment, the ANC was 0.9 × 109/L. Hydroxyurea dosing was held and resumed at a reduced dose of 24 mg/kg/d after ANC recovery in 9 days.

In high-income countries, chronic blood transfusion therapy to keep maximum sickle hemoglobin (Hb S) levels below 30% and total Hb levels greater than 9.0 g/dL is recommended for primary stroke prevention in children with SCA and high transcranial Doppler velocities based on robust evidence from 2 randomized controlled trials. After at least 1 year, hydroxyurea may be substituted for regular blood transfusions for primary stroke prevention in those without MRI evidence of cerebral vasculopathy.7 Regular blood transfusion therapy is also the recommended standard treatment for the prevention of secondary strokes.8 Hydroxyurea therapy is less efficacious than regular blood transfusion for secondary stroke prevention; a pooled analysis of several studies shows that both treatments are associated with lower stroke recurrence risk compared with no treatment (Figure 2).9 Even with regular blood transfusion therapy, 45% of children with SCA and a prior stroke will have stroke recurrence over the course of 5.5 years, suggesting that alternative therapies are needed for this high- risk population. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has shown the best efficacy in reducing stroke recurrence, but most patients have no sibling-matched donors. Recent advances in reducing the toxicities of haploidentical HSCT are being exploited to expand access to viable donors.

A hypothetical cohort of 1000 children with SCA and strokes followed for 5 years receiving either no therapy, hydroxyurea therapy, or regular blood transfusion therapy. Stroke recurrence in the no-treatment group, hydroxyurea therapy group, and regular blood transfusion therapy group have expected incidence rates of 29.1 (95% CI, 19.2-38.9), 3.8 (95% CI, 1.9-5.7), and 1.9 (95% CI, 1.0-2.9) events per 100 patient-years.

A hypothetical cohort of 1000 children with SCA and strokes followed for 5 years receiving either no therapy, hydroxyurea therapy, or regular blood transfusion therapy. Stroke recurrence in the no-treatment group, hydroxyurea therapy group, and regular blood transfusion therapy group have expected incidence rates of 29.1 (95% CI, 19.2-38.9), 3.8 (95% CI, 1.9-5.7), and 1.9 (95% CI, 1.0-2.9) events per 100 patient-years.

Hydroxyurea therapy for SCA in Africa

Several prospective studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of hydroxyurea therapy in children with SCA in Africa. Dose escalation of hydroxyurea to the MTD (~20-35 mg/kg/d) compared to a fixed moderate dose (~17-20 mg/kg/d) achieved lower incidence rates of SCA-related complications, malaria, the need for blood transfusion, and hospitalization. Clinical responses and treatment outcomes improved with hydroxyurea dose escalation with dose optimization without increasing hematologic toxicities in an open- label study with 8 years of follow-up (over 4000 patient-years) in 4 African countries.10-12

Studies in Nigeria have showed that hydroxyurea therapy instead of regular blood transfusion therapy is effective for both primary and secondary stroke prevention in children with SCA. Fixed low-dose (10 mg/kg/d) and fixed moderate dose (20 mg/kg/d) hydroxyurea had comparable efficacy in primary and secondary stroke prevention, demonstrating that 10 mg/kg/d could be considered the minimum efficacious dose for stroke prevention.13-15 However, in the primary stroke study the moderate-dose group had lower incidence rates of all-cause hospitalizations. A recent model-based pharmacoeconomic study in Uganda concluded that compared to a fixed moderate-dose regimen, dosing at the MTD is a cost-effective treatment in children with SCA.16

Despite the abundance of evidence in support of the safety and efficacy of hydroxyurea treatment—making a compelling case for its widespread use for patients with SCA in Africa— optimal dosing and toxicity-monitoring strategies are yet to be fully defined. Low-dose regimens are less costly and may not require monitoring for myelosuppression. On the other hand, moderate-dose or MTD regimens, while more costly and requiring monitoring, achieve superior clinical outcomes (Table 1). The lower cost of low-dose regimens must be balanced against the cost of more frequent hospitalization and higher rates of SCA- associated complications in comparison with MTD dosing. Accumulating hematologic toxicities data from ongoing studies show no significant difference between moderate and MTD-dosing regimens, suggesting that less frequent monitoring (2-3 times a year) after reaching the target dose may be considered safe, lowering treatment costs overall. Access to hydroxyurea is significantly hampered by affordability and availability barriers. Where hydroxyurea is available only in 500-mg capsules, dosing young children is difficult. Except for Nigeria, where the drug is locally manufactured, most countries import hydroxyurea, and even costs of $1 to $2 per week are prohibitive. Locally manufacturing quality-assured hydroxyurea helps lower costs and facilitate drug distribution. Similar barriers have been overcome for HIV through a global funding mechanism, providing a model for SCA initiatives to improve access to different formulations of hydroxyurea. The systematic education and training of health professionals (doctors and nurses) using national guidelines supported by the WHO will enhance their proficiency in prescribing and monitoring hydroxyurea therapy.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

Eighteen months into hydroxyurea therapy, the family made inquiries about curative therapies. The patient had 3 siblings, and HLA typing confirmed that the patient was HLA matched with a younger brother who has sickle cell trait. Doctors offered the family 2 referral options for transplant: a center in India where another patient in the SCD program had received a transplant the year before or a center in Nigeria. The Nigeria site was favored because of proximity and the ease of coordinating posttransplant care.

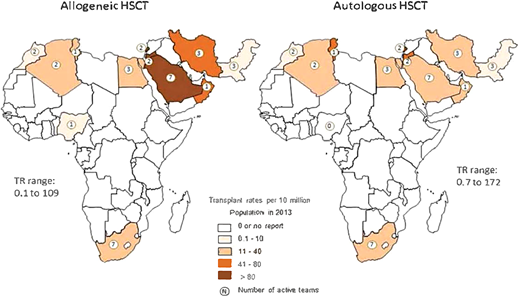

Infrastructure for allogeneic HSCT exists in only a few countries in Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa, and Tunisia) (Figure 3).17 In 2023 Tanzania joined this shortlist with the launch of its HSCT program for SCA, East Africa's first.

At the stem cell transplant center, the patient and donor were counseled about the procedure, complications, outcome, and posttransplant care and gave consent for the procedure. The patient and donor were screened for HIV, hepatitis B and C, serum iron using serum ferritin (not a reliable biomarker in SCA) because liver MRI is not readily available in Nigeria (iron overload in patients undergoing transplant is a major cause of mortality), cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, tuberculosis (via chest x-ray), ova and parasites in the stool, and malaria parasites. These are the basic investigations in low-income settings, and diseases like tuberculosis, malaria, and helminths are more common in developing countries like Nigeria. It is important to screen and treat these diseases before stem cell transplant.

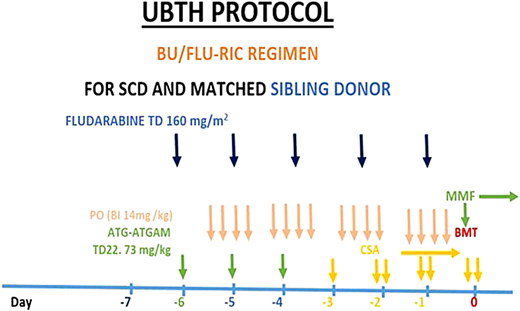

A central line was inserted, and an automated red cell exchange was conducted before a conditioning regimen to reduce the percentage of red blood cells with Hb S and the chances of a vaso-occlusive crisis occurring during the transplant procedure. Reduced intensity conditioning with busulfan, fludarabine, and antithymocyte globulin (equine) was commenced (Figure 4). The patient was admitted to an isolation room with a high-efficiency particulate air filter during the period of aplasia.

Protocol for sibling-matched HSCT for SCA at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital (UBTH), Nigeria. ATG-ATGAM, antithymocyte globulin; BMT, bone marrow transplant; BU, busulfan; CSA, cyclosporine; FLU, fludarabine; RIC, reduced- intensity conditioning; TD, total dose.

Protocol for sibling-matched HSCT for SCA at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital (UBTH), Nigeria. ATG-ATGAM, antithymocyte globulin; BMT, bone marrow transplant; BU, busulfan; CSA, cyclosporine; FLU, fludarabine; RIC, reduced- intensity conditioning; TD, total dose.

The graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis comprised cyclosporine and monomethylfumarate (MMF). The patient had antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral prophylaxis instituted because of the difficulties of diagnostic studies in developing and low-income countries.

The source of the stem cells was bone marrow, which is preferred to peripheral stem cells for SCA because it has a reduced incidence of graft-versus-host disease and better overall survival. The patient was positive for cytomegalovirus, and at day 0 we changed the prophylaxis acyclovir to valganciclovir. The patient was also positive for Epstein-Barr virus and was given rituximab at 375 mg/m2 on day 7 plus to prevent lymphoproliferative disease. The harvest was 20 mL/kg of the donor, and the yield was 6.2 × 108/kg nucleated cells. Total nucleated cells were used to calculate yield as there was no flow cytometry machine to assess CD34+ cells in the marrow. A blood component therapy of leukodepleted irradiated platelets and red cells was used during the transplant. In the absence of the conventional machine for blood component irradiation, a linear accelerator for radiotherapy delivered the recommended 25 Gy to the blood components.

Engraftment of neutrophils and platelets occurred on day plus 14 and plus 18, respectively. Chimerism at day plus 65 was 100%, and the patient was discharged on day plus 85 with a stable full blood count. Posttransplant drugs were cyclosporine and MMF. The patient experienced only grade 1 oral mucositis during the transplant and was clinically stable. Her diet was strictly monitored to reduce gastroenteritis, and MMF was tapered off by the fourth month posttransplant. The cyclosporine was also tapered off at 8 months, and the patient commenced with reimmunization with nonlive vaccines over 3 months. Hormonal assays and follow-up clinics were conducted monthly during the first year and then every 3 months for over 2 years. Infertility is a complication of the myeloablative conditioning regimen, so patients/parents are counseled, and patients of reproductive age are offered egg or sperm banking, which is available in most developing countries.

HSCT for SCA in Africa

The challenges in delivering HSCT in low-income countries across Africa are enormous. These include a lack of infrastructure, equipment for diagnosis, treatment, cell processing and storage, and trained personnel, with the few trained ones leaving for high- income countries. Also, irregular power (electricity) supplies and the depreciation of local currency exchange rates worsen the cost of transplant because most drugs are imported in US dollars with hefty tax levies. The single center in Nigeria (Celltek Healthcare Medical Center) provides transplant therapy for the equivalent of 20 000 US dollars, but this is beyond the reach of the average Nigerian. In Tanzania, the estimated cost is US $30 000, a huge contrast from the US $250 000 cost in Europe. This difference in cost is most likely due to the unavailability of advanced expensive equipment and the lower cost of support services and personnel compensation in Africa. Health insurance for transplants is also not available, meaning that patients and families must pay out of pocket. Thus, many other patients with SCA who could benefit from transplant cannot afford it. Government support falls far short of what is needed to grow and expand the transplant service capacity. For the very few who can afford it, medical tourism to seek transplant treatment outside Africa, particularly in India, is on the rise. Unfortunately, many of these patients return to their home countries where expertise and resources for posttransplant follow-up and care are lacking.

Emerging disease-modifying and “curative” treatments for SCA in Africa

Since 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration has approved 3 therapies for the treatment of SCA: L-glutamine (reduces oxidative stress), voxelotor (binds alpha-globin and inhibits Hb S polymerization), and crizanlizumab (a P-selectin inhibitor).18-20 Voxelotor was later withdrawn by its manufacturer. Ongoing clinical trials involving voxelotor and crizanlizumab have included sites in Africa, but none of these drugs have been registered for use in Africa. Pharmaceutical companies should develop pricing schemes and access pathways that are appropriate for Africa once emerging therapies are registered. Introducing these more expensive treatments in low-resource settings will be even more challenging and should not be prioritized above hydroxyurea, the more affordable option with proven clinical benefits.21

The recent Food and Drug Administration approval of 2 gene therapies for SCA—1 through a lentiviral-mediated gene addition and the other through clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/Cas 9–mediated gene disruption has generated a lot of enthusiasm.22,23 Both therapies require the ex-vivo manipulation of harvested hematopoietic stem cells, which are infused back to the patient, who has received prior myeloablative chemotherapy. The need for a complex infrastructure and myeloablative preparation, as well as the high price tag, poses significant feasibility challenges in low-resource settings. In-vivo gene-modifying approaches that do not require myeloablation and use nonintegrating vectors, making them less technically challenging, safer, and more feasible in Africa, are in the initial stages of development. The 2023 Lancet Haematology Commission on SCD recommends the accelerated development of safe and accessible cures globally and future trials to develop approaches specifically for use in low and middle-income countries.21 For Africa, however, the enthusiasm and investments in pursuing these “curative” gene therapies should not divert attention from strategies to make hydroxyurea therapy universally accessible.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Isaac Odame: no competing financial interests to declare.

Godwin Nosakhare Bazuaye: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Isaac Odame: Nothing to disclose.

Godwin Nosakhare Bazuaye: Nothing to disclose.