Abstract

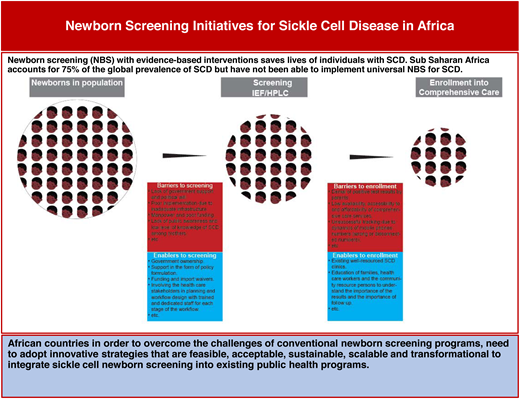

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic blood disorder in high prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) that leads to high morbidity and early mortality. Newborn screening (NBS) with evidence-based interventions saves lives of individuals with SCD. SSA accounts for 75% of the global prevalence of SCD, but it has not been able to implement universal NBS for SCD. This article examines policy framework for NBS in SSA; the methods, processes, barriers, and enablers of NBS; and enrollment in comprehensive care to make available the evidence-based interventions that caregivers need to access in order to save the lives of babies with SCD.

Learning Objectives

Appreciate the state newborn screening for SCD in Africa and the challenges preventing its widespread application

Discover NBS initiatives in Africa and innovative strategies that are feasible, acceptable, and scalable to expand NBS programs in SSA

Understand barriers and enablers to newborn screening and enrollment in comprehensive care in SSA countries

CLINICAL CASE

Baby BM, a 6-week-old girl, was identified during one of the immunization days at a primary health center in the newborn screening program of the Consortium on Newborn Screening in Africa (CONSA). Following a pre-test counseling session and consent given by the caregiver, a blood sample was obtained for confirmatory testing using the isoelectric focusing (IEF) method. The result revealed that the child had homozygous sickle cell disease, also referred to as sickle cell anemia. The baby was referred to the Paediatric Clinic of the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, Gwagwalada for prophylactic management and comprehensive care. However, the mother maintained that her baby was healthy and did not require care. Further calls to bring the baby into care were unsuccessful until the baby had an episode of severe anaemia, necessitating blood transfusion at 8 months of age.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic blood disorder in high prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) that leads to high morbidity and early mortality. Newborn screening (NBS) with evidence-based interventions saves lives of individuals with SCD. NBS is not about SCD alone. It is a 6-part system that includes education, screening (with sample collection, storage, transportation, testing, quality assurance, and external quality assurance), giving the results to the parents, parental education, follow-up, diagnosis, management, and evaluation.1 In addition to SCD, standardized NBS in well-resourced countries involves multiple disorders, including congenital hypothyroidism, phenylketonuria, and a number of inborn errors of metabolism where diagnosis and follow-up is essential to save lives.

For SCD, there is evidence from several studies justifying NBS and evidence-based interventions such as penicillin prophylaxis, pneumococcal vaccines, hydroxyurea therapy, screening for the risk of stroke with transcranial Doppler ultrasound scanning, and transfusion therapy as critical to survival in patients with SCD.2-6 Whereas high-income countries have been able to establish universal NBS programs for SCD, countries in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have had mostly pilot projects that they have not been able to scale up due to the high cost of setting up conventional NBS programs with standard IEF/high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), which require electricity, use expensive reagents, and depend on highly skilled personnel.7

The World Health Organization AFRO strategy for sickle cell disease

At the 60th session of the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Committee for Africa (RC60) in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea in 2010, the document titled “Sickle-Cell Disease: A Strategy for the WHO African Region, World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa, 2010” (AFR/RC60/8) was adopted. The strategy aimed to reduce the incidence, morbidity, and mortality of SCD in the AFRO Region by identifying priority interventions for WHO member states to develop and implement for SCD prevention and control at all levels, establishing mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation, in addition to undertaking research on SCD and applying the findings in policies and programs.8,9

An assessment of the implementation level of this regional SCD strategy in high-burden countries was carried out from November 2018 to March 2019. The results revealed that NBS is being carried out at subnational levels in some member states, with the services generally provided only in tertiary health facilities. In Mali, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Ghana samples for NBS are collected at primary and secondary levels of the health system and transported to the tertiary facilities. In Burkina Faso and Uganda, SCD NBS is integrated into HIV screening programs. In 6 other member states, NBS for SCD is integrated into reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health programs.

However, in most member states with high SCD burdens, the capacity for NBS is limited due to a number of challenges associated with conventional NBS test methods. Consequently, early detection and management of SCD are not offered at district and subdistrict primary health care facilities. A recent update on the status of NBS in SSA countries has given a good overview, as well as a detailed country-by-country account of the NBS status in the region.1,10

Screening methods

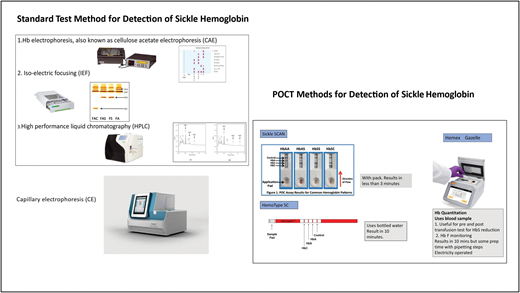

Standard methods

The standard methods for detection of SCD including in newborns and infants are cellulose acetate electrophoresis, (CAE), IEF, HPLC newborn-variants machine, and capillary electrophoresis (CE) (Figure 1). These methods have the ability to separate hemoglobin into fractions based on their isoelectric points as they migrate across a pH gradient (IEF),11 the retention time and shape of the peak as they interact with a stationary phase (HPLC),12,13 and electrophoretic mobility depending on their size and charges (CE). 14-16 They are reliable, have the ability to distinguish the most common clinically important types of SCD in Africa, are fully automated, and can take many samples in a single run.17 However, the machines are expensive to procure and maintain, and they make use of reagents and consumables that are not manufactured locally, resulting in frequent stock-outs and disruption of services. In addition, they require electricity and trained personnel to perform and interpret the results and are therefore not practical in LMICs.17

Standard and point-of-care methods for detection of sickle hemoglobin.

Point-of-care tests

The introduction of point-of-care tests (POCTs) in the last decade has presented a viable alternative and the possibility of mass universal NBS in the LMICs with high prevalence of SCD and other hemoglobinopathies. These POCTs are inexpensive, easy to use, and reliable; do not require electricity; and show high specificity and sensitivity in the discrimination of the common hemoglobin phenotypes in the presence of high fetal hemoglobin in newborns.

The most common and readily available POCTs include Sickle SCAN, HemoTypeSC. They are lateral flow immunoassays (LFIAs) that use monoclonal antibodies on lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay (LFIA) against hemoglobin S, hemoglobin C, and hemoglobin A to detect the different types of SCD qualitatively.17,18 Sickle SCAN uses a direct LFIA while HemoTypeSC uses a competitive inhibition LFIA technique. Since their introduction, several validity and performance characteristic studies in comparison with the gold standard tests (HPLC, IEF) have been conducted across the continent and have been found to have high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy.19-24

Another reliable, simple, and inexpensive POCT is the HemeChip, a microengineered cellulose acetate electrophoresis technique that has undergone validation and has a potential for use in NBS as well.17,25,26 It can detect Hb F and HbA2.

A number of studies have shown that POCTs can be applied in NBS (Nigeria, Haiti, Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, French Martinique, and more recently Gambia). However, POCTs cannot detect other hemoglobin variants such as O-Arab, D-Punjab, Hb F, and HbA2. HemoTypeSC cannot differentiate between homozygous SCD and sickle-β0-thalassemia, and the result could be misinterpreted.17 POCTs for NBS involve analyzing one sample at a time unlike IEF and HPLC, which are suitable for processing large volumes of test samples.

While questions of the ability of POCTs to tease out different Hb phenotypes remain, their inclusion in the WHO Essential Diagnostics Lists and ease of deployment with minimum infrastructure show that these tests can play a role in universal NBS in high-burden countries, especially when positive results can be taken to reference laboratories for confirmatory testing. Using dried blood spot (DBS) to run POCTs such as HemoTypeSC offers the added value of the possibility of molecular testing for Hb genotype (Table 1).

Comparison of standard test methods and point-of-care tests

| Characteristics . | Standard methods (IEF/HPLC) . | Point-of-care tests (Sickle SCAN, HemoTypeSC) . |

|---|---|---|

| Cost of machine/device | High | Low |

| Maintenance | Require regular maintenance | Do not require maintenance; one-time use and disposable |

| Reagents/consumables | Multiple reagents and consumables that require restocking and are often imported | Each test kit comes with its consumables |

| Detection of hemoglobin | Detect wider spectrum of hemoglobin variant | Detect limited number of hemoglobin variants |

| Number of samples per run | Can take many samples in a single run | Only 1 sample per run |

| Turnaround time | Take hours | Minutes |

| Cost per test | Expensive | Low cost |

| Power requirement | Require electricity to operate | Do not require electricity |

| Personnel | Require trained and highly skilled personnel to perform and interpret the test | Simple to perform and interpret |

| Mass screening | Unsustainable in low-resource countries | Has potential for deployment in mass screening in Africa with DBS for HemoTypeSC |

| Characteristics . | Standard methods (IEF/HPLC) . | Point-of-care tests (Sickle SCAN, HemoTypeSC) . |

|---|---|---|

| Cost of machine/device | High | Low |

| Maintenance | Require regular maintenance | Do not require maintenance; one-time use and disposable |

| Reagents/consumables | Multiple reagents and consumables that require restocking and are often imported | Each test kit comes with its consumables |

| Detection of hemoglobin | Detect wider spectrum of hemoglobin variant | Detect limited number of hemoglobin variants |

| Number of samples per run | Can take many samples in a single run | Only 1 sample per run |

| Turnaround time | Take hours | Minutes |

| Cost per test | Expensive | Low cost |

| Power requirement | Require electricity to operate | Do not require electricity |

| Personnel | Require trained and highly skilled personnel to perform and interpret the test | Simple to perform and interpret |

| Mass screening | Unsustainable in low-resource countries | Has potential for deployment in mass screening in Africa with DBS for HemoTypeSC |

Sample collection

The general workflow of studies on NBS initiatives conducted in Africa involves samples collection by trained lab technicians or midwives and nurses. This is carried out by heel prick or cord blood in neonates or finger prick in older infants into a DBS paper. The requirement for the collection of 2 to 5 microliters of blood into a K2EDTA sample bottle using aseptic and standard procedures for the HemeChip limits its application in the initial phase of NBS but is useful for the follow-up period. For on-site testing, eg, in the maternity ward or immunization clinic, testing with POCT is done using fresh blood samples from heel or finger pricks. For central laboratory testing, the DBS samples are air dried, packaged, and sealed in airtight and waterproof zippered storage bags containing desiccant sachets and transported to the laboratory. If the samples are not going to be run in the central laboratory immediately, the samples are stored for a limited time at room temperate or usually refrigerated at 4°C.

DBS used for IEF/HPLC have recently been shown to be effective for HemoTypeSC, as well as bringing the advantage of low cost, easy deployment, scale-up, and testing in remote areas without electricity and major expenditure in infrastructure. DBS can be stored for years, and other tests can be performed on them, including confirmatory testing.27-29 The use of DBS for HemoTypeSC opens the possibility of using this POCT to test DBS samples from other public health programs, such as the prevention of maternal-to-infant transmission of HIV, for SCD without much investment in major equipment and infrastructure. DBS POCTs also provide an opportunity to analyze batched samples at one time.

Sickle in Africa NBS Project

The SickleInAfrica Consortium funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) is carrying out an implementation science study on the use of DBS POCTs for NBS using the Consolidated Implementation Science Framework in its consortium countries of Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Zambia. Using an exploratory sequential mixed method, it seeks to assess the use of 3 technologies (standard POCT, DBS POCT, and IEF/HPLC) to facilitate NBS for SCD. The study consists of a preliminary phase involving the evaluation of the performance characteristics and cost of DBS HemoTypeSC in NBS, a quantitative phase with screening of 500 to 2500 babies across the consortium countries, and a qualitative phase with focus group discussions and in-depth interviews of stakeholders (health care workers, mothers, policymakers) to assess barriers and facilitators to DBS NBS.

NBS programs have been described in Angola, Ghana, Tanzania, Nigeria, Benin, Madagascar, Senegal Le Réseau d'Etude de la Drépanocytose en Afrique Centrale (Sickle Cell Disease Research Network) (REDAC), Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, and Liberia with details of the numbers of samples studied and the frequencies of the different genotypes—AA, AS, AC, SS, and SC with samples numbers, prevalence of Hb AA, AS, AC, SS, and SC (per country).30 However, these programs do not offer universal NBS. Therrell et al published a comprehensive update of the status of NBS blood spot screening worldwide with a very detailed overview of screening programs in Africa as well as a deep dive into all the African countries with NBS programs. Part of their conclusion was that in many settings, NBS expansion to a wide range of asymptomatic congenital disorders is successful, but in others, it has not yet been realized.10

Challenges in implementing NBS and enrollment into health facilities for comprehensive care

Challenges in implementing NBS include the protocols for NBS, costs, poorly trained health care workers, poor budgetary allocation by the government, supply chain logistics, epileptic electricity supply, high cost of equipment, nonlocal manufacturers of reagents and consumables, and the cost of running the program (Table 2).

Facilitators and barriers to newborn screening and enrollment into care

| Facilitators . | Barriers . |

|---|---|

| Newborn screening | |

| ○ Government ownership and support in the form of policy formulation, funding, and import waivers ○ Involvement of the health care stakeholders in planning and workflow design30,32 ○ Acceptability of NBS among stakeholders ○ Integration of NBS for SCD into existing services and programmes31,33 | ○ Lack of government support and political will to implement existing policies on NBS ○ Lack of public awareness and low level of education among mothers30,31 ○ Low accessibility to screening facilities31 ○ Limited diagnostic laboratory materials supply and stock-outs31,32 |

| Enrollment and follow-up | |

| ○ Existing well-resourced SCD clinics. Education of families using standardized text on the importance of follow-up30,31 ○ Government ownership ○ Funding from industry partnerships and technical support ○ Collection of proper and adequate contact information for use in tracing patients should they not return to health facility35,37 ○ Integration of NBS into maternal and child health programs in primary health care due to the cost of transport. Follow-up care should be designed for well babies instead of taking them into very busy pediatric clinics in tertiary health care centers. | ○ Denial of positive test results by parents because of apparently healthy babies within the first 6 months and stigma30,34 ○ Low availability of, accessibility to, and affordability of comprehensive care services31 ○ Unsuccessful tracking due to dynamics of mobile phone numbers (wrong or disconnected numbers)35 ○ Delay in communicating test result and relocation of family after36 |

| Facilitators . | Barriers . |

|---|---|

| Newborn screening | |

| ○ Government ownership and support in the form of policy formulation, funding, and import waivers ○ Involvement of the health care stakeholders in planning and workflow design30,32 ○ Acceptability of NBS among stakeholders ○ Integration of NBS for SCD into existing services and programmes31,33 | ○ Lack of government support and political will to implement existing policies on NBS ○ Lack of public awareness and low level of education among mothers30,31 ○ Low accessibility to screening facilities31 ○ Limited diagnostic laboratory materials supply and stock-outs31,32 |

| Enrollment and follow-up | |

| ○ Existing well-resourced SCD clinics. Education of families using standardized text on the importance of follow-up30,31 ○ Government ownership ○ Funding from industry partnerships and technical support ○ Collection of proper and adequate contact information for use in tracing patients should they not return to health facility35,37 ○ Integration of NBS into maternal and child health programs in primary health care due to the cost of transport. Follow-up care should be designed for well babies instead of taking them into very busy pediatric clinics in tertiary health care centers. | ○ Denial of positive test results by parents because of apparently healthy babies within the first 6 months and stigma30,34 ○ Low availability of, accessibility to, and affordability of comprehensive care services31 ○ Unsuccessful tracking due to dynamics of mobile phone numbers (wrong or disconnected numbers)35 ○ Delay in communicating test result and relocation of family after36 |

Training and capacity building

Training of all staff involved in the NBS using standard material is important and involves the use of protocols, pre-screening health talk, DBS collection, storage and transportation of DBS, laboratory testing, conveyance of results, follow-up and early intervention, quality assurance, and external quality assurance. Monitoring and evaluation of each step of the program are essential to ensure that the NBS is according to strict protocol.

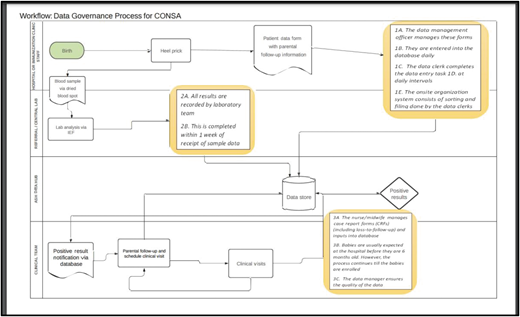

Special initiatives of NBS in Africa: American Society of Hematology CONSA

In 2017, the American Society of Hematology established CONSA as part of its global SCD initiative to demonstrate feasibility of NBS for SCD to African governments. Hematologists and public health officials participating in the consortium have mobilized networks of screening laboratories, SCD or pediatric hematology clinics, teaching hospitals, universities, and satellite clinics to screen babies and provide clinical services per the consortium protocol. These steps were the consequence of introducing standard-of-care practices for screening and early intervention therapies (such as antibiotic prophylaxis and immunizations) at participating institutions, screening, and providing clinical follow-up for babies diagnosed with SCD (Figure 2).

The following aspects of the screening program were well defined for each consortium site (see Box 1), followed by site visits to access the site readiness to abide with the consortium protocol and bylaws.

Prompt availability of oral penicillin and folic acid

Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) in consortium country

Follow-up pneumococcal vaccines with H. influenza

Ability to participate in the consortium's data reporting system with a designated data manager

Reliable internet at site

Established clinical care program that included at least 1 pediatric/pediatric hematology clinic

Demonstration of capacity for free Insecticide Treated Nets and/or antimalarial chemoprophylaxis provided to families of all patients

The presence of personnel trained in collecting DBS

A referral laboratory with certified personnel who can run the assays on IEF or HPLC and with the ability to develop adequate family education and counseling services for families of babies screened and babies enrolled in the consortium protocol

Data management workflow also specifies who will be responsible to enter the data for each aspect of the program, to perform quality checks, and to manage the data (Figure 3)

The first NBS and clinical networks launched in 2020 to screen 10 000 to 16 000 babies in each country.

Baby BM is among the 62% of babies in our CONSA program whose parents eventually accepted the diagnosis of their babies after initial denial and refusal for follow-up and enrollment in comprehensive care. Her diagnosis was not detected at birth but in the immunization clinic, emphasizing the need to integrate NBS into existing public health programs. Her parents' response illustrates the challenge we have encountered in the CONSA program where parental denial causes delay and unwillingness to access care for their babies, thereby exposing the babies to early complications of SCD and resulting in death. NBS saves lives, but parental education is important in order to enable the babies to benefit from evidence-based interventions following NBS available within the public health system in African countries, as has been illustrated in the paper by Therrell et al.1 This paper included a declaration by workshop participants, the Rabat Declaration on Newborn Screening, to help in the development of sustainable NBS programs based on collective engagement and collaboration.

Declaration

“Recognizing that newborn screening programs must function within local public health systems governed by political and societal realities in a given context;

Recognizing that there may be a need for substantial adaptations tailored to the local realities in order to accomplish the ultimate goals of early identification, treatment, and enrollment into comprehensive care;

Recognizing that sub-Saharan Africa accounts for over 75% of the global SCD burden, and appreciating that a newborn screening panel can include many different congenital conditions,

We hereby affirm that hemoglobinopathy screening should be the major focus of newborn screening programs within sub-Saharan Africa;

All countries should endeavour to establish a NBS program within the context of their national health care system.

We have identified the following activities to promote sustainable newborn screening across Africa:

Engagement with Ministries of Health to boost awareness of need for newborn screening; to request endorsement of newborn screening; and to ensure alignment with country goals;

Engagement with global health organizations—e.g., WHO and Gavi (the Vaccine Alliance) to establish collaboration opportunities for sharing resources;

Engagement with manufacturers of diagnostic equipment and supplies to collaborate with countries to promote and lower costs for newborn screening;

Engagement with pharmaceutical companies regarding treatment options for affected babies and children, especially low-cost antibiotics, and generic hydroxyurea for SCD;

Exploration of different screening methodology options, such as point-of-care diagnostic technologies to lower cost and program efficiency;

Establishment of and prioritizing a minimum list of common conditions to screen infants in Africa in the short term with SCD as the focus;

Establishment of country-based and community-based associations working on newborn screening;

Training of healthcare workers (doctors, nurses, health educators, genetic counselors, etc.) and public health laboratorians about newborn screening and genetics;

Public education about newborn screening and SCD, in particular;

Partnership with international maternal and child health, community-based, affected-family and public health organizations that have resources to assist;

Continued presentation and publication of pilot screening results;

Inclusion and education of community members and families as stakeholders in decision-making processes;

Setting up data management systems within the newborn screening programs that can enable evidence-based decision making and longitudinal tracking of SCD patients.

The successful introduction and expansion of newborn screening in Africa will require careful planning and advocacy. Some pilot programs exist with variable approaches, but sustainability requires support from country Ministries of Health (MoH). Helpful partnerships with key stakeholders are needed, including affiliations with other programs of MoH (e.g., maternal and child health, immunization, health education, etc.). In addition, developing collaborative partnerships with other countries for laboratory and clinical support could be utilized.

We have identified the following general challenges to implementing newborn screening for sickle cell diseases (SCD) and other conditions (thalassemias) in Africa:

Lack of comprehensive national newborn screening programs;

Lack of newborn screening policies and guidelines;

Lack of well-trained health workers;

Lack of the necessary laboratory infrastructure and associated systems, such as sample transport and laboratory information management systems, to enable testing and dissemination of results;

Lack of stable, consistent and sufficient funding.

We recognize the need for establishing collaborations and networks to facilitate the development of sustainable newborn screening programs in all countries.

In order to develop such a collaborative network in Africa, and to move newborn screening forward in our respective countries, we pledge to:

Participate in increased communication efforts across the continent including a regional website, biennial regional meetings and annual meetings to share resources and assess each country's progress;

Develop smaller focused topic groups to address important issues (e.g., training, clinical standards of care);

Establish a national advisory committee (including representatives of advocacy groups and affected-family organizations) for newborn screening planning;

Work with the MoH to gain national support and to address other important issues (e.g., finances, integration with other MoH programs);

Ensure standardization of data through the encouragement of the implementation of the common data elements for newborns to facilitate sharing and exchange of data within the continent as well as with the rest of the world;

Seek opportunities to train the next generation of health care and public health professionals in new technologies as applied to newborn screening (e.g., molecular genetic methods);

Work with affected families and MoH to develop, provide and continually assess templates for culturally-sensitive, multi-media educational materials, and requisite well-trained health educators.”

Conclusion

To overcome the challenges of conventional NBS programs, African countries need to find innovative strategies that are feasible, acceptable, sustainable, scalable, and transformational to integrate sickle cell NBS into existing public health programs.

Acknowledgments

Grant funding for Obiageli E. Nnodu:

NIH FIC (1D43TW012724-01) Sickle Pan African Research Consortium Training Grant (SPARC-TRAIN)

NIH NHLBI (U01HL168084) (mAnaging siCkle CELl disease through incReased AdopTion of hydroxyurEa in Nigeria— ACCELERATE)

UK NIHR (NIHR134482)—NIHR Research Group on Patient- Centred Sickle Cell Disease Management in Sub-Saharan Africa (PACTS)

NIH NHLBI (1UO1HL156942-4) Sickle Pan African Research Consortium NigEria NEtwork Cohort Study (SPARC-NEt)

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Obiageli E. Nnodu: Advisory Board-Agios, Novartis.

Chinwe Onyinye Okeke: no competing financial interests to declare.

Hezekiah Alkali Isa: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Obiageli E. Nnodu: Nothing to disclose.

Chinwe Onyinye Okeke: Nothing to disclose.

Hezekiah Alkali Isa: Nothing to disclose.