Abstract

Nearly 2 out of 3 patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE) and 1 out of 4 patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) will die within the year. Whether, when, and how to manage anticoagulation at the end of life requires many trade-offs. Patients and clinicians must balance symptom burden, greatly elevated bleeding and thrombosis risks, competing comorbidities and medications, and changing goals over time. This review uses cases of VTE and AF to present a framework for care that draws upon existing disease-specific data and cutting-edge palliative care science. It reviews strategies for the difficult task of estimating a patient's prognosis, characterizes the enormous public health burden of anticoagulation in serious illness, and analyzes the data on anticoagulation outcomes among those with limited life expectancy. Finally, an approach to individualized decision-making that is predicated on patients' priorities and evidence-based strategies for starting, continuing, or stopping anticoagulation at the end of life are presented.

Learning Objectives

Recognize the prevalence of limited life expectancy among patients taking anticoagulants

Incorporate key concepts of time to benefit and time to harm into anticoagulant decision-making

Develop an individualized framework for starting, stopping, or continuing anticoagulants based on patients' priorities

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 52-year-old man with widely metastatic lung adenocarcinoma is discharging from the hospital on hospice. He has a history of pulmonary embolism (PE), diagnosed 3 weeks earlier, for which he has been on a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC). You are consulted to discuss whether to continue therapeutic anticoagulation.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 94-year-old woman with hypertension, osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (AF). She is referred to discuss whether to initiate therapeutic anticoagulation.

Introduction

Data and guidelines are plentiful for starting anticoagulant medications but conspicuously lacking for stopping them. These decisions are particularly challenging because studies specific to this scenario are limited. Moreover, patients' priorities near the end of life may diverge from those typically measured and reported. There is added difficulty in knowing how to match available care with elicited priorities.

This review is structured around patient cases of the 2 most common indications for anticoagulant medications: the treatment and prevention of recurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE), including PE and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and thromboembolic stroke prevention in AF. It discusses evidence-based tools for estimating prognosis, examines the epidemiology of anticoagulant use in patients with serious illness, and summarizes existing evidence to apply to decision-making. These data then inform a proposed framework for whether, when, and how to treat with anticoagulants at the end of life that is based on patient goals while highlighting the imperative for additional research.

Nuances of defining who is at the end of life

The first challenge in making decisions about anticoagulation is to accurately identify who is near the end of life. For the purposes of medical decisions, “end of life” is typically defined as a life expectancy of less than 1 year.1 Estimating a prognosis can be difficult.2 For patients with a dominant terminal disease, like the patient with cancer in Case 1, the prognosis may be more straightforward but is still subject to imprecision.3 However, AF and VTE predominantly affect older adults, and chronological age, functional status, and comorbidities are equally strong predictors of mortality, as illustrated by Case 2.4 ePrognosis (https://ePrognosis.ucsf.edu) is an online repository of evidence-based prognostic indices that clinicians can use to combat assumptions and roughly estimate life expectancy when making decisions while acknowledging residual uncertainty.5,6 Inputting the characteristics of the patient in Case 1 into a prognostic calculator from ePrognosis dedicated to patients with metastatic cancer provides a life expectancy of 215 days. Driven by her advanced age and multimorbidity, the life expectancy of the patient in Case 2, using a separate ePrognosis calculator for outpatients, is 18 months.

Epidemiology of anticoagulation at the end of life

In the US, more than 10 million patients have AF, and approximately 900 000 patients are diagnosed with VTE annually, the majority of whom are eligible for anticoagulation (Table 1).7,8 Nearly 1 in 4 patients with AF dies in the year following diagnosis.9 Many patients remain on anticoagulation until death: a cross-sectional study of nursing-home residents with advanced dementia and AF found that nearly one-third remained on anticoagulation during the last 6 months of life, and those with more severe dementia and higher bleeding risk were more likely to receive anticoagulants.10 VTE also often connotes a limited life expectancy.11 In a population-based cohort study in Denmark, 3% of patients with DVT and 31% of patients with PE died within 30 days of diagnosis.12 For those who survived, an additional 13% with DVT and 20% with PE died within 1 year. For VTE, in a prospective cohort of 214 patients with cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) who died over a 2-year period, 50% continued anticoagulation until death.13 Thus, AF and VTE are associated with decreased survival, and clinicians can expect that a significant proportion of the patients for whom they prescribe anticoagulants will die within 1 year.

Time to benefit and time to harm

An important concept when considering end-of-life therapies is the anticipated time to benefit and time to harm (Figure 1).14 “Time to benefit” is defined as the time until a medication's effect is evident. If the time to benefit is long, it may exceed a patient's life expectancy.15 For AF, stroke risk is quantified on an annual scale using the CHA2DS2-VASc score and ranges from 2.2% per year to 15.2%.16 For VTE, the risk of a recurrent VTE is highest in the first month (40%), drops in months 2 and 3 (10%), and remains stable thereafter (between 3 and 10%).17 Thus, the time to benefit for stroke prevention for AF is likely longer than for recurrent VTE. The time to harm is the time required for a therapy to cause harm. If drugs have a short “time to harm,” patients may experience harms even though they die before accruing the benefits. Bleeding risk from anticoagulants is concentrated in the initial phase of therapy.18 Whether to prescribe anticoagulation should take into account a patient's life expectancy, whether this exceeds the expected time to benefit, and, weighed against the time to bleeding risk, which is highest with initiation.

Time to benefit and time to harm for anticoagulation. Time to benefit is the time until a medication's effect is evident. Time to harm is the time until a medication's harm is evident. Time to benefit is longer for AF (years) than VTE (weeks to months), while harm from bleeding occurs most often with anticoagulant initiation. Patients with shorter life expectancies (shown in gray) may die before accruing benefits from anticoagulation, especially for AF (shaded light blue) vs VTE (shaded green) but can still experience harms (shaded red) given the short time to harm.

Time to benefit and time to harm for anticoagulation. Time to benefit is the time until a medication's effect is evident. Time to harm is the time until a medication's harm is evident. Time to benefit is longer for AF (years) than VTE (weeks to months), while harm from bleeding occurs most often with anticoagulant initiation. Patients with shorter life expectancies (shown in gray) may die before accruing benefits from anticoagulation, especially for AF (shaded light blue) vs VTE (shaded green) but can still experience harms (shaded red) given the short time to harm.

Evidence to inform anticoagulant treatment decisions at the end of life for AF and VTE

Randomized controlled trials of anticoagulants for AF and VTE generally exclude patients with life expectancies of fewer than 3 to 6 months. Consequently, their results and guidelines incorporating these studies may be less applicable to patients near the end of life. Older adult patients can offer some insight because advancing age leads to shorter survival. For context, life expectancy in the US for a 90-year-old woman is 5 years and for a man, 4 years, compared to 9 years and 8 years at age 80.19 Thus, some of the most applicable information comes from examining the outcomes of very old adults with AF and VTE who, by virtue of age, may be near the end of life.

For AF, in a cohort of patients aged 75–106 years the net clinical benefit (NCB) of anticoagulant therapy with warfarin or the DOAC apixaban (ie, for the prevention of stroke) was estimated while accounting for the risk of anticoagulant-related bleeding and the competing risk of death. Overall, the NCB declined with age. However, the NCB of warfarin declined below the accepted risk-benefit threshold sooner, at age 87, compared to apixaban, which remained above the benefit threshold until age 92. This study highlights that the clinical benefit of anticoagulant therapy not only potentially declines as the end of life approaches but also varies among anticoagulant classes.20 The Edoxaban Low-Dose for Elder Care AF Patients (ELDERCARE-AF) trial examined whether NCB might be improved with reduced anticoagulant dosing. Nearly 1 000 Japanese patients over age 80 with AF who were considered inappropriate candidates for standard-dose anticoagulants (eg, due to age, low body weight, or renal insufficiency) were randomized to a reduced dose of a DOAC versus placebo.21 Reduced-dose anticoagulation prevented more strokes than placebo (HR 0.34; 95% CI, 0.19-0.61) but did not affect survival (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.69-1.36). Although the risk of major bleeding was not increased (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 0.90-3.89), low-dose DOAC did increase the risk of other bleeding events, such as gastrointestinal bleeding (HR, 2.85; 95% CI, 1.03-7.88). ELDERCARE-AF illustrates the vulnerability of this population—15% dropped out and 15% died during the 15 months of follow-up—and that lower-dose DOACs may effectively prevent stroke but cause more nonmajor bleeding overall and do not improve survival. In sum, patients with AF and a high mortality risk who are taking anticoagulants have very high bleeding and thrombosis risk, underscoring the delicate balance when making clinical decisions. When the risk of death from causes other than AF goes up, the NCB of anticoagulation is less certain, particularly with warfarin vs DOACs.

Analogous to AF, studies of VTE in very old patients provide some information: in a cohort of 3 262 participants with VTE aged 90 years and above, 17.3% had died within 90 days, and the rate of bleeding was 4.5-fold higher than that of VTE recurrence.22 Data on CAT, which is common and associated with advanced disease, is also relevant. Guidelines recommend indefinite anticoagulation for patients with VTE and ongoing active cancer based on multiple randomized controlled trials demonstrating a reduced risk of recurrence with acceptable bleeding rates, although some suggest discontinuation in the palliative setting.23-25 Importantly, these studies generally enrolled patients with longer life expectancies and good functional status.26 In a prospective observational study enrolling 334 patients with active cancer and VTE who received low-molecular-weight heparin, 35% of whom died over 1 year of follow-up, 10% experienced major bleeding and 11% recurrent VTE, both of which were highest in the first month of treatment.27 Among 214 patients with CAT who died over a 2-year period and received anticoagulation, documented clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was common (5.5%), with the majority occurring in the last week of life, and no patients experienced symptoms due to recurrent VTE.13 Although anticoagulation clearly provides a net benefit for patients with VTE and longer life expectancies, limited observational data suggest that this may not apply as patients approach death, and individualized care is paramount.

Anticoagulation outcomes for patients enrolled in hospice

While nearly 50% of persons in the US enroll in hospice for end-of-life care, enrollment tends to be delayed until near death, with a median hospice stay length of 18 days. Still, outcome observations from this patient population remain informative. Rates of anticoagulant use in hospice vary, from less than 10% to nearly 60% depending on patient population and setting.28 With regard to bleeding risk, among 1 087 patients admitted to 22 hospices in France, the cumulative incidence of bleeding was 9.8%, one-quarter of which were fatal.29 Risk factors included cancer, bleeding history, and anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication use. Anticoagulation to prevent stroke in AF does not have immediate symptomatic benefit, but a proposed benefit of anticoagulation for VTE is that it might reduce symptoms. The finding that roughly half of patients develop persistent symptoms of DVT (post-thrombotic syndrome) and PE (post-PE syndrome) despite adequate anticoagulation suggests anticoagulation may not be a panacea.30,31 Among hospice patients screened with serial ultrasound, one-third developed DVT, but this was not associated with additional symptom burden.28 Overall, retrospective data confirm that anticoagulation is started or continued in a substantial proportion of hospice patients with uncertain benefit.

Integrating anticoagulation outcomes with patients' priorities near the end of life

Outcomes measured in studies of anticoagulants, such as bleeding, thrombosis, and even death, may not match the priorities of patients with serious illness, who vary in what they consider important. Many believe certain conditions—including bowel or bladder incontinence or needing care from others—to be worse than death.32 Additionally, patients exhibit significant diversity in the type of care they desire near the end of life. Some patients are willing to accept virtually any treatment no matter how burdensome to prolong life, some would make only certain trade-offs in quality of life for more time, and still others prize quality above all else, including survival.33 With advancing illness, some patients become less willing to accept the burdens of treatment to avoid death, while others become more willing to undergo invasive therapies for any chance of improved health.33,34 The diversity and mutability of patients' goals emphasizes that the decision to start, continue, or stop anticoagulants near the end of life must be personalized and reassessed.

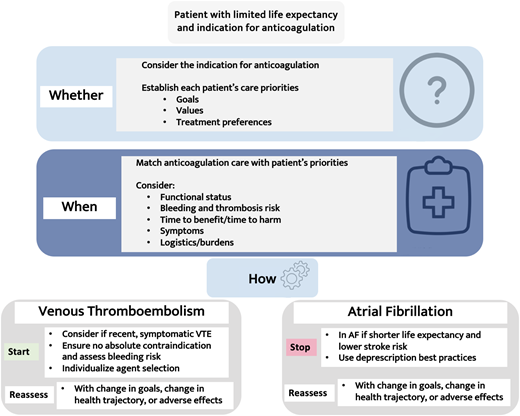

Framework for treatment decisions near the end of life: patient priorities

A robust body of evidence shows that using decision tools for patients with serious illness can improve treatment decision-making.35 One example is the patient priorities care framework, in which clinicians help patients and caregivers identify the following: (1) values, (2) specific outcome goals, (3) health care preferences (eg, medications that are feasible and helpful vs burdensome), and (4) the top priority. When implemented, the framework reduces burdensome treatment and unwanted health care and possibly leads to more shared decision-making and healthy days at home.36,37Figure 2 superimposes the specifics of anticoagulation onto this framework, integrating patients' priorities, prognosis, and risk of major bleeding vs thrombosis within their remaining life span. Dedicated tools are needed to facilitate evidence-based shared decision-making, such as using natural frequency expressions (eg, “out of 100 people like you”) and illustrative pictographs, and serious illness communication, such as how to express uncertainty and avoid overstating benefits.38 Although based on extrapolated evidence as outlined above, if a patient has had a recent (<3 months) VTE, particularly a PE or extensive DVT, and is symptomatic, still ambulatory, and does not have an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation or excessive bleeding risk, this favors anticoagulation if it meets their goals (see the visual abstract). The severity of the VTE and the patient's bleeding risk can be factored into whether to use a DOAC loading dose (eg, apixaban 10 mg twice daily for 7 days) or not. For AF, starting or continuing anticoagulation is less favorable unless a patient is at an exceedingly high risk of stroke (eg, a recent stroke or a history of multiple strokes) or places a high value on stroke prevention. If starting or continuing anticoagulation, this decision should be reassessed frequently, especially with changes in their health trajectory.

Using patients' priorities to guide anticoagulation treatment decisions near the end of life.

Using patients' priorities to guide anticoagulation treatment decisions near the end of life.

If anticoagulation is pursued, clinicians should first exclude absolute contraindications (Table 2).39 Risk factors for bleeding should be evaluated and modified if feasible, including avoiding unnecessary antiplatelet agents and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, minimizing hypertension, and considering a proton pump inhibitor to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding.

Medication options are the same as for patients with longer life expectancies with several unique considerations as outlined in Table 3. These include a discussion of timing (once vs twice daily) and preferred mode of administration (for example, due to nausea some patients may even prefer low-molecular- weight heparin injections over oral agents).40 Decreased or inconsistent nutritional intake can affect the absorption and metabolism of warfarin and DOACs, particularly rivaroxaban.41 Difficulty swallowing or the presence of a feeding tube affect agent selection: dabigatran cannot be crushed, whereas rivaroxaban and apixaban can be given as an oral solution or via a nasogastric tube. The absorption of crushed pills is affected by both food and enteral nutrition.42 While vitamin K is readily available and affordable for warfarin reversal, DOAC reversal agents require transfer to a hospital, which may not be within the goals of care.43 Cost can be a barrier to continuing anticoagulation as patients near the end of life, as such medications may not be covered for hospice patients. As always, drug-drug interactions, concomitant renal or hepatic dysfunction, and the logistics of monitoring for warfarin are also important factors to weigh and reassess.

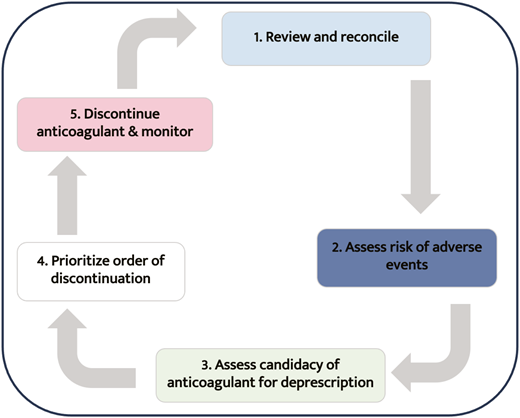

Patients taking anticoagulants who want to stop should have these medications deprescribed. Deprescribing is an evidence-based approach to the supervised cessation of medications with the goal of improving outcomes.44,45Figure 3 outlines the steps involved in deprescription relevant to anticoagulants.

CLINICAL CASE 1 (continued)

He identifies his priorities as symptom relief and spending time with family and hiking. He has no additional bleeding risk factors. Apixaban is affordable, and he is not bothered by twice-daily oral administration. He elects to continue apixaban, with a plan for monthly reassessment.

CLINICAL CASE 2 (continued)

The patient identifies her goals as reducing the number of medications she is taking and avoiding invasive care and hospitalization. She states, “When it's my time, it's my time” when discussing the possibility of stroke. She uses occasional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for chronic knee pain. After shared decision-making incorporating these goals and considering that anticoagulation's time to benefit may exceed her life expectancy of 18 months and subject her to a short-term risk of increased harm from bleeding (potentially exacerbated by her comorbidities and medications), she forgoes anticoagulation.

Conclusions

The prevalence of conditions treated with anticoagulant medications is increasing. As more patients become eligible for anticoagulants, it is imperative that we recognize how many may have limited time to benefit from treatment and yet still be exposed to harms. Future studies should prioritize this population and ensure that outcomes like symptoms or days spent at home are measured so that decisions can be informed. Anticoagulation at the end of life will always require the difficult task of balancing trade-offs. By eliciting patients' priorities, we can work to provide individualized care that is concordant with their values and relieves their suffering.

Acknowledgment

Anna L. Parks is supported by research funding from the National Institute on Aging, K76AG083304.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Anna L. Parks: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Anna L. Parks: No off-label drug use to report.