Learning Objectives

Review the association between inherited thrombophilia and recurrent miscarriage

Discuss key evidence informing anticoagulation use and pregnancy outcomes in women with inherited thrombophilia and recurrent miscarriage

CLINICAL CASE

A 32-year-old woman was referred to you at 15 weeks gestation regarding anticoagulation management. She has a history of 2 prior miscarriages at weeks 12 and 15, and she reports that she has a homozygous prothrombin gene mutation (PGM). She denies any personal or family history of venous thromboembolism. How would you approach anticoagulation in this patient?

Introduction

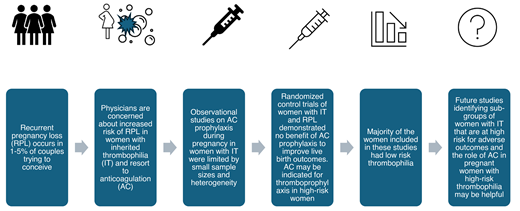

Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) affects 1%-5% of couples, placing a significant psychological and physical burden on women and families and increasing health care costs. The etiology for RPL remains unexplained in half of the cases despite extensive evaluation, and physicians and patients resort to treatment modalities that have uncertain benefit in an attempt to achieve a healthy live birth. Inherited thrombophilia (IT) has been associated with increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) during pregnancy and the postpartum period. The association of IT with placenta-mediated pregnancy complications, including pregnancy loss, small-for-gestational-age fetus, preeclampsia, and placental abruption, has remained controversial for several years due to discordant results from various studies.1,2 In this review, we summarize key studies examining the association between IT and RPL and studies examining the role of anticoagulation in preventing pregnancy loss in women with IT and a history of miscarriage. VTE prevention and outcomes in acquired thrombophilias, such as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, are outside the scope of this review.

Inherited thrombophilia and pregnancy outcomes

Common ITs include factor V Leiden (FVL) and prothrombin G20210A (PGM) mutations, and deficiency of natural anticoagulants, protein C, protein S and antithrombin III. The risk of VTE during pregnancy in these disorders varies widely depending on the underlying mutation (odds ratio [OR] of 3.19 for protein S deficiency, to 34.4 for women with homozygous FVL mutation compared to those without IT) (Table 1). Their associations with pregnancy-related outcomes showed lower absolute risks.2 The European Prospective Cohort on Thrombophilia study showed increased risk of still birth or late fetal loss with thrombophilia, although the likelihood of a positive outcome is high in both women with thrombophilia and in controls, with no clear benefit of anticoagulation.3 A meta-analysis of 10 prospective studies showed a weak association between FVL and late pregnancy loss.4 A recent meta-analysis of 89 studies involving 30 254 individuals demonstrated an association of RPL with FVL and PGM mutations (homozygous or heterozygous) in first and second trimesters and an association of protein S deficiency with late term fetal loss, but no association of RPL with antithrombin or protein C deficiency. The majority of the studies included in this meta-analysis did not control for confounders and included very few patients with high-risk thrombophilia, such as homozygous FVL and PGM (Table 2).5 These studies were plagued by heterogeneity in study population, outcomes, and small sample sizes and demonstrated low absolute risk for RPL in IT or no clear association between the two conditions, leading to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines recommending against routine testing for IT in women with RPL.6

Anticoagulation and pregnancy outcomes in inherited thrombophilia

The pathophysiology of adverse pregnancy outcomes in thrombophilia is multifactorial, and thrombosis of placental vasculature is unlikely to be the sole mechanism.7 While guidelines exist for thromboprophylaxis during pregnancy and the postpartum setting in women with IT,6,8,9 some physicians have adopted low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) for management of women with IT and RPL due to presumed benefit of anticoagulation, extrapolating from studies in patients with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. A review of the literature identified 10 randomized controlled studies (RCTs) and 10 observational studies (Table 2) evaluating the effect of anticoagulation on live birth rates in women with IT and a history of pregnancy loss.

A prospective cohort study including 126 women with a thrombophilia and history of pregnancy loss showed increased live births with LMWH (OR 10.6; 95% CI, 5.0-22.3), concluding that LMWH was beneficial in preventing pregnancy loss.10 However, there was no reduction in adverse pregnancy outcomes with LMWH compared with placebo in the Thrombophilia in Pregnancy Prophylaxis trial (risk difference, -1.8%; 95% CI, -10.6% to 7.1% in intention-to-treat analysis), with increased risk of minor bleeding with LMWH.11 A Cochrane review of aspirin, LMWH, or both in women with RPL showed no difference in live birth rates or other obstetric complications when these treatments were compared to a placebo.12 A meta-analysis of observational studies suggested improved live birth rate,13 but a meta-analysis of 8 RCTs in IT and pregnancy loss did not show a significant difference in live birth rate with the use of LMWH compared with no LMWH (relative risk [RR] 0.81; 95% CI: 0.55-1.19).14 The recently completed randomized controlled ALIFE2 study enrolled 326 women with IT and ≥2 pregnancy losses and showed no difference in live birth rates or other adverse pregnancy outcomes with LMWH compared to standard of care (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.65 to 1.78; absolute risk difference: 0.7%), supporting that there is no benefit of anticoagulation to improve live birth rate.

Does type of thrombophilia matter?

The discrepancy in findings from observational studies and RCTs emphasizes the heterogeneity and confounding factors in interpretation of these studies. Most of these studies included White individuals and patients with low-risk thrombophilia; some included participants with nonconventional ITs, such as a methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) mutation or a plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) polymorphism (Table 2). These studies highlight the lack of evidence specifically in high-risk thrombophilias, which are managed distinctly within guidelines for VTE risk reduction in pregnancy even in women with no personal or family history.8 This also provides an opportunity to conduct further studies in diverse populations with high-risk thrombophilia. It is extremely challenging to recruit patients in these clinical trials, as seen with ALIFE2 study, which took several years to recruit patients despite multinational collaboration, but we can agree upon the recommendations against routine antepartum LMWH prophylaxis in women with heterozygous FVL or PGM mutations.15

Risks with anticoagulation

Anticoagulant use in pregnancy, as in any situation, must be weighed against the risk of complications related to bleeding. A Cochrane review of aspirin or anticoagulant use in women with RPL demonstrated no increased risk of bleeding with aspirin alone, but an increased risk when LMWH was used in combination with aspirin (RR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.6-3.24).12 The ALIFE2 study revealed no difference in bleeding between women treated with LMWH vs placebo, though 45% of women treated with LMWH experienced bruising compared to 10% of control participants.16 In addition to bleeding, anticoagulation during pregnancy is inconvenient, increases the risk of osteopenia, adds to health care costs, and gives false hope to women.

Conclusions

Empiric anticoagulation during pregnancy in women with IT and RPL has not been confirmed to confer any benefit regarding pregnancy outcomes other than thromboembolism prevention in high risk women.

Screening for IT is not recommended for women with RPL, as there is insufficient evidence that antepartum thromboprophylaxis improves the live birth rate (conditional recommendation, very low certainty in evidence about effects).

Patients with IT and RPL do not benefit from prophylactic LMWH, as it has not been shown to increase live birth rate, and we do not recommend routine use of anticoagulation to improve pregnancy outcomes in these individuals (conditional recommendation, very low certainty in evidence about effects).

RCTs have repeatedly demonstrated no benefit of antepartum anticoagulation to improve live birth rate in women with IT and RPL and provide reassurance to women with thrombophilia. The ACOG guidelines recommend low dose aspirin for women at high risk of preeclampsia but not specifically for RPL.17 In our patient with homozygous PGM and RPL, antepartum anticoagulation is not likely to increase the chance of a live birth. The American Society of Hematology guidelines suggest against antepartum anticoagulation in the absence of a family history of thrombosis, but postpartum thromboprophylaxis is recommended to prevent a first VTE.9

Future directions

There is insufficient evidence to recommend anticoagulation as an intervention to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with IT. Future research delineating the role of placental pathology and subgroups of women with a thrombophilia that might benefit from anticoagulation would be helpful.

Acknowledgments

Radhika Gangaraju received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL159290) and the American Society of Hematology and research support from Sanofi.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Leslie Padrnos: no competing financial interests to declare.

Radhika Gangaraju served as a consultant for Sanofi, Bayer, Takeda and Alexion.

Off-label drug use

Leslie Padrnos: Nothing to disclose.

Radhika Gangaraju: Nothing to disclose.