Abstract

Reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens have been investigated for more than 10 years as an alternative to traditional myeloablative conditioning regimens. RIC regimens are being commonly used in older patients as well as in disorders in which traditional myeloablative conditioning regimens are associated with high rates of non-relapse mortality. Hodgkin disease, myeloma, and low-grade lymphoid malignancies have been the diseases most impacted by RIC regimens. RIC regimens have also been shown to be safe and effective in older patients as well as patients with co-morbidities, although patients with chemorefractory disease still have high relapse rates and poor outcomes. Patients with chemosensitive disease have outcomes similar to those obtained with conventional ablative therapies, and thus comparative trials are warranted. RIC regimens are associated with lower rates of severe toxicity and non-relapse mortality; however, infections, graft-versus-host disease, and relapse of primary disease remain the most common obstacles to a successful outcome. The impact on survival and the relative benefits of RIC allografting compared with traditional conditioning regimens or alternative therapy remain to be defined. Incorporating targeted therapies as part of the conditioning regimens or as maintenance therapies is currently being explored to reduce relapse rates without increasing toxicity.

When initially developed, allogeneic progenitor cell transplantation was conceived as a method of rescuing patients from the toxic side effects of dose-intensive chemoradiotherapy. The relevance of dose intensity was underscored by two randomized trials that demonstrated lower relapse rates in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with increasing doses of radiotherapy.1 The lower relapse rate did not translate into an improved survival due to higher non-relapse mortality (NRM) rates.

The increased NRM rates seen in more intensive regimens is partially due to increases in rates of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) mortality, which is related to the intensity of the preparative regimen.2 Storb et al,3 using canine models, showed that a low dose of total body irradiation (TBI) could provide sufficient immunosuppression to allow hematopoietic donor cell chimerism, along with an antileukemic effect, without the potentially lethal effects of an intensive, myeloablative preparative regimen. These observations, together with the demonstrated antitumor effect of donor lymphocyte infusions, led to the exploration and development of reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens as a strategy that would allow harnessing the graft-versus-tumor effect without the toxicities of myeloablative therapies.

Since the early 1990s many groups of investigators have explored strategies using less intensive preparative regimens that would allow engraftment of hematopoietic progenitor cells from either identical or non-identical donors. These less intense regimens result in less tissue damage, less inflammatory cytokine secretion, and possibly lower rates of GVHD and NRM.4–8 In this article, we review the current use and current controversies affecting the field of RIC regimens for hematologic malignancies.

Defining RIC Regimens

Traditional myeloablative regimens produce severe myelosuppression that, without stem cell support, translates into severe and prolonged pancytopenia. So called RIC regimens have been defined based on the following characteristics9:

Reversible myelosuppression (usually within 28 days) without stem cell support.

Mixed chimerism in a proportion of patients at the time of first assessment.

Low rates of non-hematologic toxicity.

In practice, based on both published experience and expert opinion, the Center for International Blood and Marrow Research (CIBMTR) and the National Marrow Donor Program have used one or more of the following criteria to define an RIC regimen:10–12

≤ 500 cGy total-body irradiation;

≤ 9 mg/kg total busulfan dose;

≤ 140 mg/m2 total melphalan dose;

≤ 10 mg/kg total thiotepa dose;

usually includes a purine analog—fludarabine, cladribine, or pentostatin.

The most common reduced intensity regimens are presented in Table 1 .

Current Use of RIC Regimens: Impact on Recipient Age

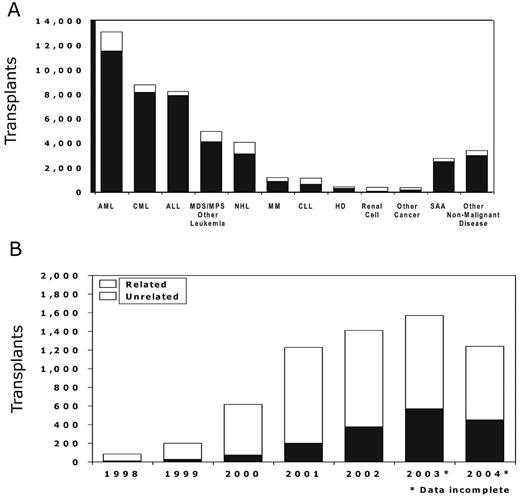

Over the last 5 years the use of RIC regimens for allogeneic progenitor cell transplantation has increased significantly. Data reported to the CIBMTR are summarized in Figure 1A and BF1. More than 4000 progenitor cell transplants were performed after RIC regimens in 2002, representing almost 25% of all allogeneic transplants reported to the CIBMTR during that year. The most common diseases in which reduced intensity regimens are being explored are AML, non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and plasma cell disorders (CIBMTR data, Figure 1A ).

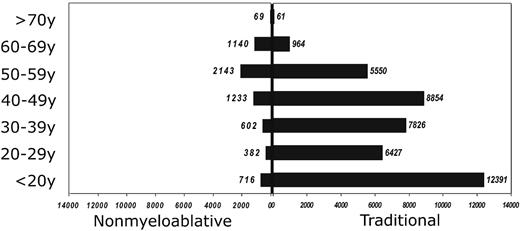

Reduced-intensity regimens have expanded the applicability of allogeneic transplants to older patients. The percentage of patients older than 55 years undergoing allografts has increased steadily since the advent of reduced-intensity regimens. Figure 2 demonstrates that for patients over the age of 60 the most common conditioning regimens are reduced intensity. Likewise, the median age of recipients of unrelated donor cells was 53 years of age if they had received a reduced-intensity regimen versus 33 years of age for recipients of a traditional myeloablative conditioning regimen.13

Are Reduced Intensity Regimens Associated with Lower NRM Rates than Traditional Myeloablative Regimens?

Various retrospective analyses have shown that RIC regimens are associated with lower NRM rates compared with traditional transplant conditioning regimens. Diaconescu et al14 reviewed the transplant outcomes from patients at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center receiving either a traditional ablative regimen or an RIC regimen of 200 cGy TBI with or without fludarabine. One-year NRM was 30% for ablative patients compared to 16% for recipients of the RIC regimen (P = 0.04). Most deaths among ablative patients occurred during the first 3 months after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), whereas most deaths among the recipients of the RIC regimen occurred between 3 and 6 months. Valcarcel et al15 analyzed the transplant outcomes of 157 consecutive adult patients who received HSCT from a HLA-identical sibling of whom 57 had RIC and 100 had standard transplants. In a multivariate analysis, NRM was associated with the use of a standard preparative regimen (hazard ratio 5.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.3–12.8), and overall survival was also associated with use of a standard preparative regimen (risk ratio [RR] 3.4; 95% CI 1.2–5.7). Similar results were also seen in recipients of unrelated donor transplants.16 These retrospective analyses compared traditional myeloablative conditioning regimens with TBI or oral busulfan. However, recent results with intravenous busulfan based regimens combined with either fludarabine or cyclophosphamide have been associated with low NRM rates.17 Thus in suitable patients a randomized trial of high-dose intravenous busulfan based regimens with lower-intensity regimens may be appropriate.

Are All Reduced-Intensity Regimens Equal?

De Lima et al18 recently reported that among patients with AML or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) receiving one of two RIC regimens, the risk of relapse-related mortality was significantly less for patients receiving a more intense regimen of fludarabine and melphalan than those receiving a regimen of fludarabine, cytarabine, and idarubicin (0.26 vs 0.53), whereas the 3-year NRM rate was significantly higher for recipients of the more intensive RIC regimen (0.39 vs 0.15). Recent retrospective analysis of data from the NMDP as well as the Société Française de Greffe de Moelle failed to demonstrate an impact of the type of RIC regimen on transplant outcome on a variety of hematologic malignancies.13,19 However, the impact of dose intensity may be different in different hematologic malignancies and therefore, at present, RIC regimens should not be considered equivalent, since their impact on chimerism and their anti-neoplastic efficiency may be different.

Table 1 depicts the most commonly used RIC regimens ordered by their myelosuppressive activity. Chimerism kinetics may be different for these regimens as well. Childs et al20 demonstrated that patients receiving fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide first developed T-cell donor chimerism, and later myeloid donor chimerism, as opposed to patients receiving melphalan- or busulfan-based combinations, with which most patients have either complete or almost complete donor cell engraftment in both lineages at the time of neutrophil recovery.

Have RICs Changed the Standard of Care for Any Hematologic Malignancy?

Allogeneic transplants with RIC regimens could potentially change the standard of care for a variety of hematologic malignancies by fulfilling any of the following criteria:

Make allografting feasible in patients for whom traditional myeloablative conditioning is associated with unacceptable risk of NRM;

Improve event-free survival when compared to alternative transplant and non-transplant therapies;

Prevent short- and long-term toxicities of myeloablative conditioning regimens (e.g., preservation of fertility).

Currently RIC regimens have primarily expanded access to allografting to patients considered poor candidates for traditional myeloablative conditioning regimens, but have yet to be shown to be superior to alternative transplant or non-transplant therapies. Table 2 shows ongoing randomized trials of RIC regimens being performed in North America under the auspices of the Bone Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network or other North American cooperative groups.

In the absence of phase III trials, most physicians are making therapeutic decisions regarding the potential use of RIC regimens in their patients based on single-institution case series or registry data. The following diseases have the most compelling RIC transplant data.

Hodgkin Disease

Early reports of allogeneic transplant outcomes for Hodgkin disease showed poor survival (< 25%) and high NRM (> 50%). Few allogeneic transplants for Hodgkin disease were being performed prior to the advent of RIC regimens.

Results with reduced-intensity regimens for Hodgkin disease have been summarized in Table 3 . NRM rates less than 30% have been reported in all series. Patients with chemosensitive disease, and those receiving more intensive RIC regimens, seem to have better outcomes.21,22 These promising results suggest that the most relevant question to answer at this time would be a comparison of RIC allografting to conventional autografting in patients with Hodgkin disease failing primary therapy.

Multiple Myeloma

As with Hodgkin disease, conventional allografting for myeloma has been associated with a high rate of NRM. Although outcomes have improved during the last decade, the lack of a survival benefit compared with autografting in both prospective and retrospective analysis has limited the use of allotransplantation.23 RIC regimens have decreased NRM rates to less than 30% in the salvage setting and less than 20% when transplant is performed during the early phases of the disease. The data summarized in Table 3 have led to the design and implementation of various randomized trials defining the role of allogeneic transplants after RIC regimens in the initial therapy of multiple myeloma.24–26

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Chemosensitive relapse of follicular lymphoma has been associated with some of the best reported outcomes for reduced-intensity transplant regimens.27,28 However, patients with follicular lymphoma have multiple other treatment options that can also be associated with long-term disease control without the risk of GVHD. The role of allogeneic transplantation for follicular lymphoma in contrast to other available salvage therapies needs further study.

For diffuse lymphoma, single-institution and registry data conclude that patients with chemorefractory disease do poorly. The strategy of an autologous transplant followed by a reduced-intensity allograft also needs prospective testing.21,29

Mantle cell lymphoma has been associated with a high risk of relapse after conventional chemotherapy and/or autotransplantation. Khouri et al30 reported 82% event-free survival and 86% overall survival among 18 patients allografted with fludarabine/cyclophosphamide-based reduced-intensity regimens. Maris et al31 also reported encouraging outcomes for patients with recurrent mantle cell lymphoma undergoing allogeneic transplant after a low-dose TBI regimen with an overall survival of 65% at 2 years. These results compare favorably with fludarabine-cyclophosphamide regimens, and could be the basis of future phase III trials.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has been considered a good target for RIC allografting. Dreger et al32 reported the results of 77 patients with CLL reported to the European Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. The NRM rate of 18% at 1 year and the event-free survival rate of 56% at 2 years suggests that this therapeutic option should be compared to other non-transplant therapies in patients failing frontline therapy. Sorror et al33 reported the results of a low-dose TBI RIC regimen for the treatment of advanced CLL. With NRM of 22% at 2 years and a 52% event-free survival at 2 years, this strategy also warrants further study in CLL.

Acute Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndromes

One of the major accomplishments of RIC regimens has been to allow allografting for older patients.34–37 The largest series are summarized in Table 3 . Although long-term survival in remission patients is consistently > 40%, it remains to be determined how much impact RIC allografting has on the overall outcome of older patients with AML or high-risk MDS.

Summary and Future Directions

RIC allografting has expanded the role of allogeneic transplantation to many patients who until recently were deemed ineligible for this procedure. Although thousands of patients have undergone RIC regimen allografts, only a minority of them have been cured of their disease. As with conventional allografting, GVHD and disease recurrence remain the main barriers to overcome. Current strategies being explored to improve RIC allografting outcomes have focused on combining targeted therapies such as rituximab, imatinib, and gemtuzumab as part of the preparative regimen or as maintenance strategies.38–40 Immunotherapeutic strategies with either vaccines or cellular therapies, particularly NK cell infusions, are also likely to become subject of increasing study.41,42

Most commonly used reduced-intensity regimens as reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Research (CIBMTR) by ascending myelosuppressive intensity.

| Regimen . | % . |

|---|---|

| Abbreviations: TBI, total body irradiation. | |

| Fludarabine ± others | 10 |

| Fludarabine/TBI ± others | 31 |

| Fludarabine/cyclophosphamide ± others | 17 |

| Fludarabine/busulfan ± others | 27 |

| Fludarabine/melphalan ± others | 15 |

| Regimen . | % . |

|---|---|

| Abbreviations: TBI, total body irradiation. | |

| Fludarabine ± others | 10 |

| Fludarabine/TBI ± others | 31 |

| Fludarabine/cyclophosphamide ± others | 17 |

| Fludarabine/busulfan ± others | 27 |

| Fludarabine/melphalan ± others | 15 |

Ongoing randomized trials of reduced-intensity regimens in North America.

| Organization . | Disease . | Study . | Question Being Asked . |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMT-CTN 01-02 | Myeloma | Phase III randomized study of tandem autologous stem cell transplantation with or without maintenance therapy after the second transplantation versus single autologous stem cell transplantation followed by matched sibling nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with stage II or III multiple myeloma | Role of a graft-versus-myeloma effect in achieving long term disease control |

| BMT-CTN 02-02 | Follicular lymphoma | Phase II/III study of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or non-myeloablative allogeneic HSCT from a HLA-matched sibling donor in patients with recurrent grade I or II follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Role of a graft-versus-lymphoma effect in achieving long term disease control |

| FHCRC-1813.00 | Various | Phase III randomized study of nonmyeloablative conditioning comprising low-dose total body irradiation with versus without fludarabine followed by HLA-matched related allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with hematologic malignancies at low or moderate risk for graft rejection | Role of fludarabine in engraftment and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after a reduced-intensity regimen with 200 cGy of total body irradiation (TBI) |

| Organization . | Disease . | Study . | Question Being Asked . |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMT-CTN 01-02 | Myeloma | Phase III randomized study of tandem autologous stem cell transplantation with or without maintenance therapy after the second transplantation versus single autologous stem cell transplantation followed by matched sibling nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with stage II or III multiple myeloma | Role of a graft-versus-myeloma effect in achieving long term disease control |

| BMT-CTN 02-02 | Follicular lymphoma | Phase II/III study of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or non-myeloablative allogeneic HSCT from a HLA-matched sibling donor in patients with recurrent grade I or II follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Role of a graft-versus-lymphoma effect in achieving long term disease control |

| FHCRC-1813.00 | Various | Phase III randomized study of nonmyeloablative conditioning comprising low-dose total body irradiation with versus without fludarabine followed by HLA-matched related allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with hematologic malignancies at low or moderate risk for graft rejection | Role of fludarabine in engraftment and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after a reduced-intensity regimen with 200 cGy of total body irradiation (TBI) |

Results of large series of reduced-intensity regimens for hematologic malignancies.

| Series . | Disease . | Regimen . | NRM . | OS . | Favorable Prognostic Factors . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *At 1 year; †at 1.5 years; ‡at 2 years; §at 3 years. | |||||

| Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CR, complete remission; F, fludarabine; FC, fludarabine/cyclophosphamide; FM, fludarabine/melphalan GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; MCL, mantle cell leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; NRM, non-relapse mortality; OS, overall survival; TBI, total-body irradiation. | |||||

| Robinson et al21 | Hodgkin disease | Various | 24%* | 46%‡ | Chemosensitive disease |

| Anderlini et al22 | Hodgkin disease | FM/FC | 22%† | 61%† | FM |

| Kroger et al25 | Myeloma | FM | 18%* | 59%‡ | Chemosensitive disease and limited chronic GVHD |

| Maloney et al24 | Myeloma | 200 cGy TBI (auto/allo) | 15%* | 78%‡ | |

| Crawley et al26 | Myeloma | Various | 26%‡ | 40%§ | Early disease |

| Khouri et al30 | MCL | FC +/− rituximab | 15%‡ | 86%‡ | Rituximab |

| Maris et al31 | MCL | F+ 200 cGy TBI | 24%‡ | 65%‡ | Remission patients |

| Dreger et al32 | CLL | Various | 18%* | ||

| Sorror et al33 | CLL | F+ 200 cGy TBI | 22%‡ | 60%‡ | |

| Niederwieser et al34 | AML/MDS | F+ 200 cGy TBI | 19%‡ | 45%‡ (CR1) | |

| Sayer et al35 | AML/MDS | Various | 53% | 52%‡ (CR1) | Lower disease burden |

| Ho et al36 | MDS | FM+Campath | 5% Sibs* 21% MUDS* | 73%* | Alemtuzumab given for GVHD prophylaxis |

| Wong et al37 | AML/MDS | Various | 55% * | 44%* | Remission status most important prognostic factor |

| Series . | Disease . | Regimen . | NRM . | OS . | Favorable Prognostic Factors . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *At 1 year; †at 1.5 years; ‡at 2 years; §at 3 years. | |||||

| Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CR, complete remission; F, fludarabine; FC, fludarabine/cyclophosphamide; FM, fludarabine/melphalan GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; MCL, mantle cell leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; NRM, non-relapse mortality; OS, overall survival; TBI, total-body irradiation. | |||||

| Robinson et al21 | Hodgkin disease | Various | 24%* | 46%‡ | Chemosensitive disease |

| Anderlini et al22 | Hodgkin disease | FM/FC | 22%† | 61%† | FM |

| Kroger et al25 | Myeloma | FM | 18%* | 59%‡ | Chemosensitive disease and limited chronic GVHD |

| Maloney et al24 | Myeloma | 200 cGy TBI (auto/allo) | 15%* | 78%‡ | |

| Crawley et al26 | Myeloma | Various | 26%‡ | 40%§ | Early disease |

| Khouri et al30 | MCL | FC +/− rituximab | 15%‡ | 86%‡ | Rituximab |

| Maris et al31 | MCL | F+ 200 cGy TBI | 24%‡ | 65%‡ | Remission patients |

| Dreger et al32 | CLL | Various | 18%* | ||

| Sorror et al33 | CLL | F+ 200 cGy TBI | 22%‡ | 60%‡ | |

| Niederwieser et al34 | AML/MDS | F+ 200 cGy TBI | 19%‡ | 45%‡ (CR1) | |

| Sayer et al35 | AML/MDS | Various | 53% | 52%‡ (CR1) | Lower disease burden |

| Ho et al36 | MDS | FM+Campath | 5% Sibs* 21% MUDS* | 73%* | Alemtuzumab given for GVHD prophylaxis |

| Wong et al37 | AML/MDS | Various | 55% * | 44%* | Remission status most important prognostic factor |

Use and indications for reduced-intensity conditioning regimens as reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Research (CIBMTR)

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; HD, Hodgkin disease; MCL, mantle cell leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MM, multiple myeloma; MPS, myeloproliferative syndromes; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NRM, non-relapse mortality; OS, overall survival; SAA, severe aplastic anemia; TBI, total-body irradiation.

Use and indications for reduced-intensity conditioning regimens as reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Research (CIBMTR)

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; HD, Hodgkin disease; MCL, mantle cell leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MM, multiple myeloma; MPS, myeloproliferative syndromes; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NRM, non-relapse mortality; OS, overall survival; SAA, severe aplastic anemia; TBI, total-body irradiation.

Age distribution of traditional and RIC regimens as reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Research (CIBMTR).

Age distribution of traditional and RIC regimens as reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Research (CIBMTR).