Abstract

Over the past four decades, there have been dramatic improvements in survival for patients with thalassemia major due in large measure to improved iron chelators. Two chelators are approved for use in the United States and Canada, parenteral deferoxamine and oral deferasirox. Three are available in much of the rest of the world, where oral deferiprone is also approved (in the United States, deferiprone is only available in studies, for emergency use, or on a “compassionate-use” basis). Many trials and worldwide clinical experience demonstrate that each of the three drugs can chelate and remove iron, and thereby prevent or improve transfusional hemosiderosis in thalassemia patients. However, the chelators differ strikingly in side-effect profile, cost, tolerability and ease of adherence, and (to some degree) efficacy for any specific patient. The entire field of chelator clinical trials suffers from the fact that each drug (as monotherapy or in combination) has not been tested directly against all of the other possibilities. Acknowledging the challenges of assessing chelators with diverse properties and imperfect comparative data, the purpose of this review is to summarize the last 4 years of studies that have improved our understanding of the applications and limitations of iron chelators in various settings for thalassemia patients, and to point out areas for much-needed future research.

Introduction

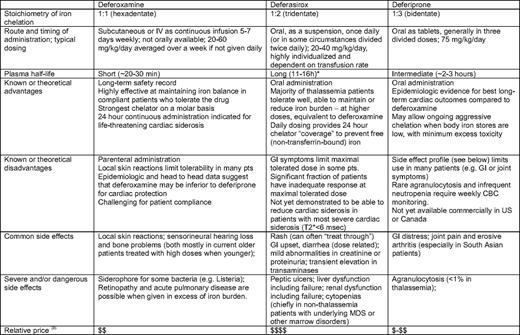

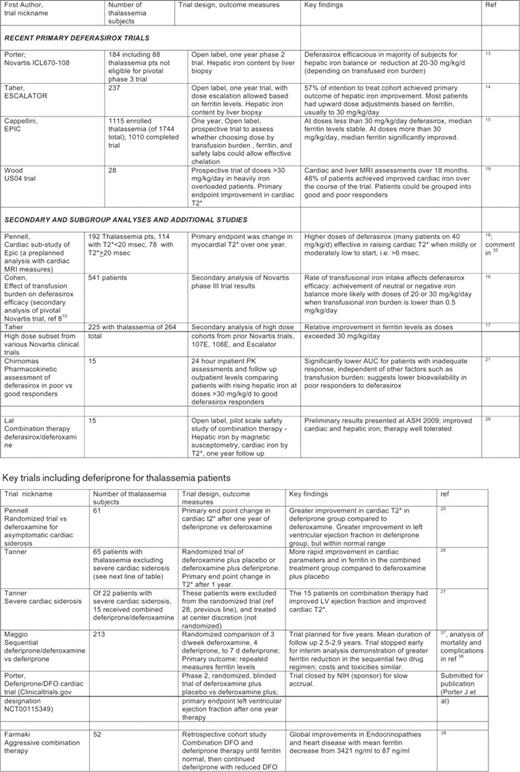

Properties of the iron chelators deferoxamine, deferiprone, and deferasirox are compared in Table 1. Beyond the scope of this review are the use of chelators for myelodysplastic syndrome1 and novel chelator applications such as in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases2 or treatment of infections based on sequestration of iron.3 Deferoxamine, with 40 years of accumulated use, is still highly relevant (e.g., in combination regimens), but new monotherapy trials of this drug are few and it is usually included only as a comparator. Since 2006, more than 100 publications each on the use of deferasirox and deferiprone in thalassemia have been listed on PubMed, but only a small fraction of these are primary reports of clinical trials, key secondary analyses from trials, or informative studies of pharmacokinetics and ancillary biology. Recent reviews have provided additional information about deferiprone,4,5 deferasirox,6 and optimizing chelation strategies.7,8 From the large pool of references, selected key studies of both drugs are summarized in Table 2 and in the text below.

Deferasirox

Update on Clinical Trials

When chelation in thalassemia was last reviewed for the ASH Hematology Education Program in 2006,9 deferasirox (Exjade®, Novartis) had only recently achieved US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval based upon the pivotal phase 3 randomized study of deferasirox vs. deferoxamine in pediatric and adult thalassemia patients,10 as well as phase 2 studies in adults11 and children12 with thalassemia. Subsequently, primary trial results were reported from a large, phase 2 study that included non-hemoglobinopathy disorders as well as thalassemia patients ineligible for the pivotal trial because they were intolerant of deferoxamine.13 More recently, two additional large, open-label clinical trials of deferasirox monotherapy have been published. The ESCALATOR trial was the first to test doses of deferasirox above 30 mg/kg.14 Conducted predominantly in the Middle East, this was the first large-scale study for which ferritin levels were used as a defined index for deferasirox dose adjustments in a heavily iron-overloaded population at baseline. Finally, the primary results of the multinational EPIC trial are now available.15 This study includes many disorders other than thalassemia, but more than 1000 thalassemic subjects.

Secondary manuscripts analyzing in-depth the characteristics of deferasirox use from these manufacturer-sponsored trials have examined critical questions about deferasirox efficacy and dosing. Cohen et al. examined the effect of transfusion burden on deferasirox chelation effectiveness in a pivotal trial, demonstrating that transfusion burdens in excess of 0.5 mg Fe/kg body weight/d were associated with a higher chance of rising iron burden (assessed in that trial by liver biopsy at the start and after 1 year).16 Taher et al. presented reassuring safety data on patients who had received doses of deferasirox above 30 mg/kg/d17 (the original upper limit approved by FDA; in 2009, based on these and related data, the upper limit of dosing was raised to 40 mg/kg/d). Pennell et al. reported cardiac status in a preplanned subgroup analysis of the large EPIC trial, focusing on patients at risk of heart disease, and demonstrated efficacy of deferasirox in the improvement of myocardial iron.18 Patients with severe and symptomatic cardiac dysfunction were not included in this trial. A prospective, investigator-initiated trial by Wood et al. also found that in patients with moderate, but not severe, cardiac iron overload (as assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] transverse relaxation time [T2*] values), deferasirox could improve cardiac siderosis in about one-half of heavily iron-overloaded patients (with hepatic iron status as a key determinant of success).19

Due most likely to patients' preference and their ability to adhere to prescribed therapy, deferasirox has become the predominant chelator over deferoxamine in North America over just a 3-year span since its initial commercial launch. As of mid-2009, deferasirox was being used in the majority of thalassemia major patients on chelation in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)-sponsored Thalassemia Longitudinal Cohort study of about 400 thalassemia major patients from the United States, Canada, and London (58% vs. 27% on deferoxamine as monotherapy, and a small number on combinations).20

Knowledge about the side-effect profile of deferasirox has been evolving since its commercial launch in 2006, as often happens with drugs new to the market. The current FDA-approved label includes a boxed warning related to post-marketing data and pharmaco-vigilance reports of bleeding peptic ulcers and both hepatic and renal dysfunction, sometimes severe. Close monitoring for toxicity is suggested by the manufacturer.

While the large majority of deferasirox users tolerate the drug well, a greater challenge to deferasirox monotherapy is that it is insufficiently effective at reducing high iron burden (or maintaining low iron burden) in a significant minority of patients (up to 30% in several reports). Potential reasons for the limited effect in these patients might include inadequate dosage, problems with compliance, or simply iron burden in excess of chelator capacity.16,19,21 Recent availability of an intravenous preparation of deferasirox (for investigational use only) has allowed pharmacokinetic assessments of bioavailability and volume of distribution,22 and a radiolabeled form allows detailed description of metabolism in thalassemic patients.23 We have studied patients with inadequate responses in liver iron or ferritin at doses above 30 mg/kg and compared them against patients with good response at lower doses. The two groups are distinguished by much lower exposure (area under the concentration/time curve) in the poor responders, an effect likely due to differential bioavailability (and not compliance or transfusion burden alone).21

Deferiprone

The oral chelator deferiprone (Ferriprox®, Apopharma, and others) is not approved in the United States or Canada, but it is approved as a second-line agent in Europe and is used as the primary agent for iron overload in some parts of the world, including southern Asia. The drug is still under consideration by the FDA. Several interesting studies over the past 4 years have highlighted an apparent advantage of deferiprone in speeding removal of cardiac iron in patients without advanced cardiac dysfunction from iron overload. These studies have been incremental in nature. In 2006, Galanello et al. reported results of a randomized trial demonstrating that deferiprone given 5 d weekly alternating with deferoxamine 2 d weekly was as successful as continued deferoxamine in lowering serum ferritin and liver iron.24 Pennell et al. then demonstrated improved myocardial T2* in a randomized trial in the deferiprone arm in patients without heart disease.25 Next, Tanner et al., in a randomized trial, showed that the combination of deferoxamine + deferiprone achieved more rapid improvement in cardiac parameters and ferritin levels compared with deferoxamine + placebo in patients with asymptomatic and mildly low cardiac T2* MRI assessments.26 The Tanner group also presented non-randomized follow-up data from patients excluded from their randomized trial. Among those patients were 15 with severe cardiac iron overload, who responded well to combined deferiprone/deferoxamine.27 A logical next step from that trial would have been a randomized evaluation of the same arms (deferoxamine + deferiprone vs. deferoxamine + placebo) in symptomatic heart disease, and indeed such a trial was launched by the NIH-supported Thalassemia Clinical Research Network, but the trial was closed early due to slow accrual. Results have been submitted for publication.

An interesting chart-review study from Farmaki et al.28 explores a cohort of patients treated prospectively in a single-center setting with a regimen of aggressive combination chelation with deferoxamine + deferiprone to start, and then reduction of deferoxamine after ferritin levels normalized; the results showed dramatic endocrinologic improvement and little toxicity While this regimen as described is based in part on the (unproven) hypothesis that deferiprone is the least toxic among the chelators at low iron burden, the literature does not provide much guidance on relative safety among the chelators as iron status approaches normal. This kind of regimen would probably not be possible with deferasirox monotherapy in the absence of direct safety trials, because the therapeutic margin for this drug does not support aggressive chelation when the body iron stores are normal. (The manufacturer suggests a drug holiday for deferasirox at ferritin levels less than 500 ng/mL, for example).

Deferoxamine

The role of deferoxamine in the armamentarium against transfusional iron overload continues to evolve. The experience with this drug goes back to the 1960s, and the advent of convenient subcutaneous pumps and compelling data for subcutaneous efficacy led the way for widespread deferoxamine therapy beginning more than 30 years ago. A subset of U.S. and European patients prefer deferoxamine to the oral options presently, and another subset of patients have returned to deferoxamine if deferasirox was ineffective or intolerable for them.

The main challenge now with deferoxamine is to understand how best to use it in combination regimens. As noted above for deferiprone, various examples of overlapping or sequential use of deferiprone and deferoxamine have been reported. Only very preliminary trials of deferasirox and deferoxamine in combination have been published. In this case, clinical practice may be outstripping the speed of clinical science, because many patients unresponsive to deferasirox alone have been started on combination with deferoxamine at our site and others. Unfortunately, aside from recent pilot safety studies,28,29 few data are published on what might be the optimum way to use deferoxamine and deferasirox together.

Management of Severe Iron Overload, Combination Therapies, and Head-To-Head Clinical Trials

Where do the recent studies described here leave the field in understanding chelator therapy for severe complications, in particular cardiac disease from severe myocardial iron overload? Since the work of Davis and Porter a decade ago, continuous high-dose deferoxamine has been one accepted approach to congestive heart failure,30 and now other strategies are in use as well. Understanding that cardiac disease incidence increases markedly at low cardiac MRI T2* values (high cardiac iron)31 has led by extension to the use of intensive regimens, including deferiprone monotherapy,32 for the treatment of low T2* itself as a surrogate marker of cardiac risk. To date, it has not been demonstrated that deferasirox monotherapy, even at high doses, is a satisfactory substitute for continuous deferoxamine in the setting of the most severe cardiac iron overload, but deferasirox alone does seem to be effective for many patients with moderate cardiac iron overload and T2* > 6 msec.18,19 In the absence of perfect comparative clinical trial data, as noted below, combination therapy with deferoxamine + deferiprone (recently reviewed by Galanello et al.33 ) is used by many centers for patients with overt cardiac arrhythmia, heart failure, or very low T2*.

To date, no head-to-head trial of the two oral chelators has been launched, either in patients with significant cardiac siderosis or in those without. The scientific rationale for such a trial is manifold. Deferiprone is much less expensive than deferasirox, but must be taken several times a day and requires more safety monitoring (Table 1). Of course, as shown by other chronic conditions such as hypertension, the model of multiple-agent therapy if monotherapy fails has been well established for decades. The safety of such an approach in iron overload of thalassemia remains to be tested, but the logic of possible enhanced efficacy (at the cost of inconvenience of multiple agents) remains.

Cost and International Perspectives on Iron Assessment and Chelation Strategies

In a disorder such as thalassemia, for which the majority of patients live in the developing world, the high cost of new therapies such as deferasirox cannot be ignored. Viprakasit et al. have addressed the current state of affairs for chelators in Asia.34 Cohen has pointed out a vital corollary to the EPIC trial cardiac substudy results, namely that if doses near 40 mg/kg/d of deferasirox are required for optimal monotherapy in many patients, the cost per patient per year may be on the order of $80,000 (based on US wholesale prices).35

Imperatives for Future Chelator Research in Thalassemia

In 2010, heart disease from transfusional iron overload is the main cause of death from thalassemia major in countries with safe, adequate blood supplies. While life expectancy continues to improve, the fact remains that optimal individualized chelation has not been achieved for many patients. Adherence to prescribed chelator regimens is an area that deserves great attention, distinct from the biological activity of the chelators themselves. Additional trials of combination chelators are needed. The author suspects that it will be impossible for these to be randomized among the currently available medications, for both practical and ethical reasons. For example, with effective oral drugs now available, it is unlikely that subjects will accept randomization to deferoxamine arms any longer. This is an opportunity to use methods of comparative effectiveness research to compare strategies for improving iron overload even when confounders are present among patient populations. This will be the job for the next several years in our field.

Disclosure

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has received research funding from Novartis and Ferrokin.

Off-label drug use: Combination chelation regimens are discussed.

Correspondence

Ellis J. Neufeld, MD, PhD, Division of Hematology, Children's Hospital Boston, 300 Longwood Ave., Karp 08210, Boston, MA 02115; Phone: (617) 919-2139; Fax: (617) 730-0934; e-mail: ellis.neufeld@chboston.org