Abstract

Younger patients (defined as patients younger than 50–55 years of age) represent a small group of newly diagnosed patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, accounting only for 10% to 20% of newly diagnosed cases. However, once these patients become symptomatic and require treatment, their life expectancy is significantly reduced. Therapeutic approaches for younger patients should be directed at improving survival by achieving a complete remission and, where possible, eradicating minimal residual disease. Chemoimmunotherapy combinations carry the highest response rates and are commonly offered to younger patients. Additional strategies that should be considered for younger patients include early referral for stem-cell transplantation and clinical trials of consolidation therapy to eliminate minimal residual disease.

Epidemiology and Characteristics of Younger Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

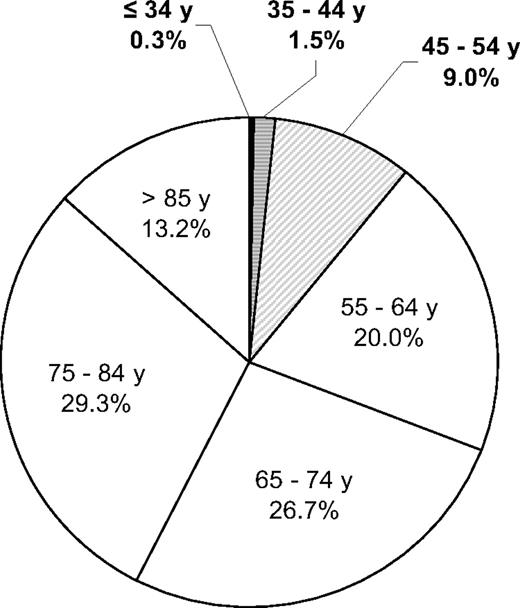

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most prevalent type of adult leukemia in the Western world. It is rare before the fourth decade of life, and its incidence increases exponentially after age 40. The upper age limit for definition of patients with CLL as “younger” has varied between 50 and 55 years in published reports,1–5 but the designation usually refers to individuals in their 40s and 50s. Based on the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance and Epidemiology End Results (SEER) program estimates, 11% of the 15,490 patients diagnosed with CLL in 2009 in the United States were age 54 or younger6 (Fig. 1). A similar proportion of younger patients have been reported in European studies. In an Italian series of 1011 patients with CLL between 1984 and 1994, 20% of the patients were 55 years of age or younger.3 Similarly, 14.3% of the patients were younger than 50 years of age in a review of 929 patients in Spain between 1980 and 2008.4 Published studies from Bennett1 and Molica5 in Europe also indicated that between 7% and 12% of their CLL population was younger than 50 years.

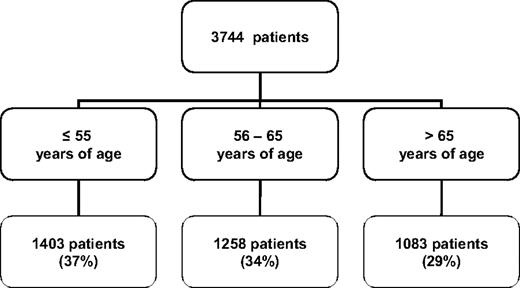

Although younger patients represent a small group of newly diagnosed patients with CLL, they account for up to one-third of the patients that are referred to specialized medical centers. Based on a review of 3744 patients with CLL referred to the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center between 1970 and 2009, 37% of the patients were age 55 or younger (Fig. 2). Younger patients are more likely to participate in clinical trials for reasons that include better performance status, lower incidence of severe comorbidities, and a different attitude toward the diagnosis of CLL and available treatment options. Younger patients also experience significant psychosocial stress related to the diagnosis of CLL due to repercussions for work/employment status, impact on spouse/partners, and responsibility toward children and family.

Age distribution of CLL patients at the time of referral to M.D. Anderson Cancer Center

Age distribution of CLL patients at the time of referral to M.D. Anderson Cancer Center

Several retrospective studies have summarized the clinical characteristics of younger patients with CLL. Differences in clinical features at presentation and in the traditional prognostic factors such as stage, lymphocyte-doubling time, and bone-marrow histology between younger and older patients with CLL were not found in these earlier studies. Demographic data reported by Monserrat2 and Mauro3 did, however, show a higher male-to-female ratio in younger patients.

New prognostic markers have been described for CLL over the last decade. These include the presence of genomic abnormalities detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization or by array-based karyotyping, immunoglobulin heavy gene somatic mutation (IgVH) status, expression of ZAP 70, the thymidine-kinase activity of neoplastic cells, and beta2-microglobulin levels. Döhner et al. found that the impact on survival for patients carrying a deletion 11q was greater in patients 55 years of age and younger.7 A large study by Shanafelt et al.8 reviewed the utility of prognostic testing in patients with CLL categorized according to age at diagnosis. In this study, 593 patients were younger than 55 years and, with the exception of a larger number of patients with Rai stage I-II disease, the remainder of the prognostic factors were similarly distributed among younger and older patients. Stage was found to be a powerful predictor for time to first treatment and overall survival (OS) in all age groups. After adjusting for stage and IgVH status, the expression of ZAP-70 and fluorescence in situ hybridization abnormalities remained significant predictors of both time to first treatment and OS time in patients younger than 55 years.

Treatment Considerations in Younger Patients

Younger patients with CLL have a longer survival time than their older counterparts. According to SEER data, the 5-year relative survival rate of patients younger than 55 years in the United States is 88%. Only 3.7% of patients dying with CLL are younger than 55 years6 . However, when compared with their age-matched control population, the life expectancy of younger patients with CLL is significantly reduced. Mauro et al. reported that the 10-year expected survival probability for younger patients with CLL was significantly lower (45% vs. 96%) than that of sex- and age-matched controls in their study.3 Shanafelt et al. also found a decreased survival (p < 0.001) for patients younger than 55 years with respect to the age-matched general population.8 While younger age by itself should not be considered a reason to initiate therapy, the therapeutic goal in the case of a young patient requiring therapy should focus on improving survival by achieving a complete remission and, when possible, eradicating minimal residual disease (MRD). The importance of achieving a complete remission is highlighted by the finding that a better quality of remission is associated with longer survival times.

The results of two randomized trials presented at the 2009 ASH meeting showed a survival advantage for patients with CLL who were treated with fludarabine as opposed to chlorambucil or with chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) as opposed to combination chemotherapy. The first study was a long-term update of a study conducted by Rai et al. randomizing patients to receive initial therapy with chlorambucil, fludarabine, or the combination of chlorambucil + fludarabine, and showed a survival advantage starting 6 years after treatment initiation in patients that received fludarabine as the initial therapy.9 The second study was conducted by the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG) and included patients with symptomatic CLL and good performance status who were randomized to receive treatment with fludarabine + cyclophosphamide with (FCR) or without rituximab (FC); longer disease-free survival and OS were seen in the patients who received FCR.10

Initial Therapy: Chemotherapy and CIT Combinations

Treatment with single-agent purine nucleoside analogs such as fludarabine, pentostatin, or cladribine achieves complete response rates of 20% to 30%. Following these initial results, combination therapies such as FC were developed. Combining these two agents was based on in vitro data showing that fludarabine inhibits repair of cyclophosphamide-induced DNA inter-strand cross-links, suggesting the presence of complementary activity between the two.11 The FC combination was studied in phase II clinical trials,12 and was compared with single-agent fludarabine in phase III clinical trials.13,14 The FC combination was found to give a 35% complete response rate that was superior to that of single-agent fludarabine.

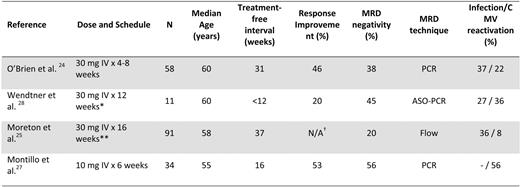

CIT combinations of purine nucleoside analogs with or without alkylating agents and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies have been developed in recent years following the demonstration in preclinical models that the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab sensitized CLL cells to the apoptotic effects of fludarabine (Table 1). These regimens were found to be very active, with complete response rates between 40% and 70%. Because the CIT trials have enrolled younger patients with good performance status and no severe comorbidities, the results of these studies are most relevant to the treatment of younger patients with CLL.

Chemoimmunotherapy regimens as initial treatment

β2M, beta-2-microglobulin; CR, complete remission; OR, overall remission; PFS, progression-free survival; Rai III/IV, Rai stage III or IV

* Listed in order of number of patients enrolled (N);

†time to treatment failure;

‡Binet stage C;

§NR, not reached at 15.4 months median follow-up;

#results combined for concurrent and sequential FR.

Tam et al.15 reported the long-term results of the FCR combination as initial therapy in 300 patients with symptomatic CLL. The median age of the patients was 57 years, with 43% of the patients younger than 55 years. The overall response rate in the 128 patients who were age 55 years or younger was 96% (76% complete response, 12% nodular partial response, 8% partial response; Keating et al., personal communication). Accompanying that study, MRD in the bone marrow after therapy was measured by flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction. The achievement of marrow negativity by flow cytometry was associated with a longer time to progression and longer survival time. Similarly, a negative MRD status as measured by polymerase chain reaction was predictive of a better outcome. These results demonstrate the impact of quality of remission on remission duration.

Further insight into expected outcome for patients undergoing FCR therapy can be gained by the analysis of treatment results based on IgVH status published by Lin et al.16 IgVH status was obtained in 177/300 patients treated with FCR. Data obtained prior to therapy were combined with data obtained by DNA extraction from paraffin-imbedded archival tissue. While no difference in response rate or achievement of marrow-flow negativity between patients with mutated and non-mutated IgVH was noted, patients with mutated IgVH had a longer remission duration and survival. This finding is in agreement with the reports of Catovsky et al. showing an impact of IgVH mutation status on progression-free survival (PFS) in patient treated with either fludarabine or the FC combination.13 Woyach et al.17 updated the results of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 9712 trial, and showed a superior OS time for patients with mutated IgVH.

A phase III study comparing FCR with FC in 817 patients with symptomatic CLL was conducted by the GCLLSG.10 Patients enrolled in this study had a median age of 61 years. Treatment with FCR was associated with a higher overall response rate (95% vs. 88%; p < 0.01) and a higher complete response rate (44% vs. 22%; p < 0.01) than the FC combination. FCR was also associated with a longer median PFS (52 months vs. 33 months; p < 0.001) and a superior OS (87% vs. 83%; p = 0.012) at 3 years. This study also incorporated assessment of MRD as measured by flow cytometry. Based on results achieved in the peripheral blood 2 months after treatment, an MRD level under 10–4 was associated with superior PFS and was achieved more frequently (66% vs. 34%; p < 0.0001) in the FCR-treated patients.

Other combination chemotherapy and CIT regimens have achieved similarly high response rates in younger patients with CLL. Bosch et al.18–19 reported the results of two trials, the combination of fludarabine + cyclophosphamide + mitoxantrone (FCM) and the combination of FCM + rituximab (RFCM). The FCM study was designed for patients younger than 65 years, while the RFCM included patients up to the age of 70 years. The proportion of patients age 60 or younger was 64% in the FCM and 48% in RFCM trial. The overall response rate was 90% in the FCM trial and 93% in the RFCM trial, with complete response rates of 64% and 82%, respectively. In both trials, MRD was measured by flow cytometry. Negativity for MRD was obtained in 26% of the complete responders in the FCM trial and in 56% in the RFCM trial.

The CALGB reported results of a randomized study of 104 patients with a median age of 63 years using the combination of fludarabine + rituximab (FR) administered in a concurrent or sequential manner. The overall and complete response rates were higher than in prior studies using single-agent fludarabine20 . Kay et al.21 published results using pentostatin + cyclophosphamide + rituximab (PCR) as initial therapy of patients with symptomatic CLL. The median age in this study was 63 years. The overall response rate was 91%, with a complete response rate of 41%; the median PFS time was 33 months.

Ofatumumab, a novel, fully humanized monoclonal antibody, was evaluated in combination with fludarabine + cyclophosphamide in patients with untreated CLL. The patients in this trial were randomized to receive two different doses of ofatumumab (500 or 1000 mg). A total of 51 patients with a median age of 56 years were enrolled in this study. In patients who received the higher dose of ofatumumab, the combination of ofatumumab + fludarabine + cyclophosphamide was associated with an overall response rate of 73% and a complete response rate of 50%.22

The GCLLSG evaluated bendamustine in combination with rituximab in a phase II trial.23 The overall response rate was 91% and the complete remission rate 33%. Eradication of MRD by flow cytometry was achieved in 58% of the evaluable patients.

Consolidation Therapy: Eradication of MRD

Assessment of MRD has become an important end point in evaluating the quality of responses in clinical trials. Elimination of MRD has been associated with prolonged response duration in several phase II and phase III clinical trials with CIT as the initial treatment. Eradication of MRD may be particularly relevant for younger patients, because this population benefits the most from longer response durations and also has the ability to tolerate more intensive treatments in order to achieve this goal. Similarly, the relevance of low MRD levels as a predictor for PFS and OS has been demonstrated in several prospective trials and retrospective data reviews that have shown longer disease-free survival in patients who received consolidation therapy.24–29

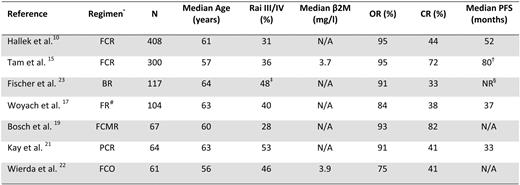

Several consolidation strategies (e.g. alemtuzumab, rituximab, lenalidomide) aiming to eliminate MRD are being investigated in clinical trials. Most experience has been accrued with alemtuzumab, and the results are summarized in Table 2. While several of these studies have shown that alemtuzumab consolidation is efficacious in achieving an MRD-negative state and results in better clinical responses and response duration, it is important to recognize that this treatment can be associated with myelosuppression, opportunistic infections, and other complications, and that these may offset its clinical benefit.30 Alemtuzumab should be administered within clinical trials and not before at least 6 months have passed from the last chemotherapy regimen.

Recurrent Disease

Younger patients with recurrent disease pose a particular challenge. The choice of subsequent treatment is based on multiple factors, including patient age, fitness status, the type of first-line treatment that was used, the quality and duration of response obtained with the first line of therapy, and individual patient characteristics. For the latter, the most important considerations are the presence or absence of unfavorable chromosomal abnormalities such as deletion 17p and/or 11q and whether the patient has developed resistance to treatment with purine analogs. It seems reasonable to offer the same or similar treatment plan to patients who have had a response with initial therapy that was longer than 2 to 3 years. Patients who have received initial therapy with single-agent alkylating agents, purine analogs, or a combination of these can achieve a significant benefit from treatment with CIT. Dmoszynska et al.31 demonstrated that in patients with recurrent disease, the FCR combination is associated with a higher overall response rate (70% vs. 58%), higher complete response rate (24% vs. 13%), and a longer PFS (30.6 vs. 20.6 months) than the FC combination.

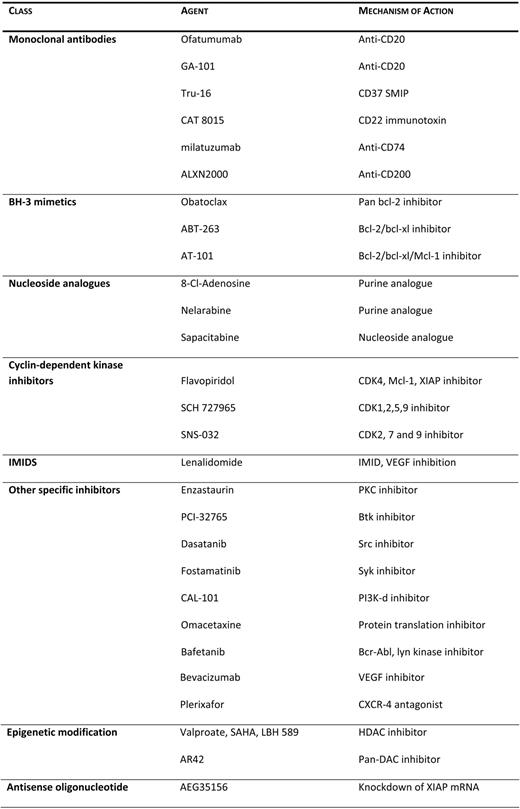

Keating et al.32 reviewed the results and the long-term outcome of 115 patients treated with various salvage strategies between 2000 and 2009 following first-line treatment with FCR. While the overall response rate was 61%, the complete response rate was significantly lower (15%). In this series, a worse outcome was observed for patients who had nodular partial responses and partial responses to salvage therapies, higher beta-2-microglobulin at the start of therapy, and more advanced stages of the disease. Once a patient, regardless of age, has developed refractoriness to fludarabine, the prognosis is dismal, with median survival times ranging between 9 and 12 months.33 These patients should be offered participation in clinical trials, since currently available therapies, including the monoclonal antibodies alemtuzumab and ofatumumab, are associated with a low response rate (5%–33%) and short-lasting responses.34 Several agents currently being investigated in patients with recurrent CLL are summarized in Table 3.

Agents undergoing investigation in CLL

Akt, Ak transforming; bcl, b-cell lymphoma; BH-3, Bcl-2 homology domain 3; Btk, Bruton's tyrosine kinase; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; CXCR4, CXC chemokine receptor; HDAC, histone deacetylase; IMID, immunomodulator; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; mcl, myeloid cell leukemia; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; SMIP, small modular immunopharmaceutical; src, sarcoma; syk, spleen tyrosine kinase; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

Allogeneic Stem-Cell Transplantation

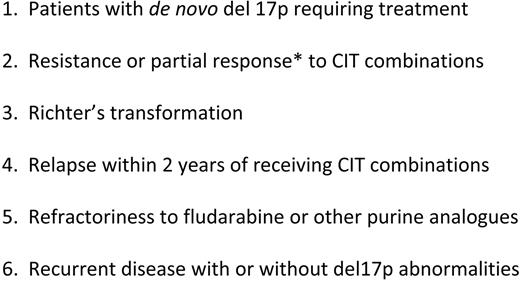

Allogeneic stem-cell transplantation (SCT) is the only curative treatment modality for patients with CLL. The number of allografts, in particular non-myeloablative SCTs (NSCTs), performed in patients with CLL has increased exponentially over the last decade. The European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation released guidelines for consideration for SCT in patients with CLL, including younger patients, in 2007.35 Patients who have fludarabine-refractory disease, patients with recurrent disease within 2 years of intensive treatment, and patients with P53 abnormalities requiring treatment should be considered candidates for SCT. Some of the high-risk features that warrant evaluation for SCT in younger patients with CLL are summarized in Table 4.

Indications for SCT in younger patients with CLL

*Partial response due to residual disease, not residual cytopenias

NSCTs are playing an increasingly import role in patients with CLL. The advantages of NSCT are reduced treatment-related mortality compared with conventional allogeneic transplants, the possibility of allowing post-transplantation immunomanipulation, and preservation of the graft versus leukemia (GVL) effect.36

There is well-documented evidence of a GVL effect in CLL, which is supported by the attainment of clinical and molecular responses with the withdrawal of immunosuppressive treatment, as well as the clinical responses following the post-transplant administration of donor lymphocyte infusions and rituximab.37 Furthermore, recipients of unrelated-donor or non-T-cell-depleted grafts and patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) have a lower rate of recurrence of CLL than recipients of related-donor or T-cell-depleted grafts and patients without evidence of GVHD, respectively.38–42

There are a number of prospective and retrospective series from individual institutions that have evaluated various NSCT regimens and immunosuppressive strategies; one of the largest reported is that of Sorror et al.38 Eighty-two patients with advanced CLL underwent NSCT from related or unrelated donors. The median age in this population was 56 years. The conditioning regimen consisted of a 2-Gy total-body irradiation alone or combined with fludarabine. Using this therapeutic approach, the investigators were able to induce an overall response rate of 70% and to achieve complete remission in 55% of the patients. The 5-year OS in this study was 50%. Factors that were associated with an inferior outcome in this series were high tumor bulk (nodes > 5 cm), the presence of comorbidities, and refractoriness to fludarabine.

Khouri et al.43 recently reviewed the outcome of 86 patients with relapsed/refractory CLL enrolled in sequential NSCT clinical protocols at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. The median patient age was 58 years. This patient population was heavily pretreated, and 23% of them expressed P53 in their leukemic cells by immunohistochemistry. The conditioning regimen consisted of FCR. The reported long-term results showed an estimated survival rate of 51% at 5 years. A proportion (50%) of these patients received immunomanipulation with rituximab and donor lymphocyte infusions after the NSCT. Such a strategy was successful in inducing complete and durable responses (the complete response rate was 47%), giving further evidence that the GVL effect can be enhanced after NSCT in CLL. In this study, an immunoglobulin G level below normal and CD4 under 100 mm3 were predictive of shorter survival time and HLA-genotype-predicted response to immunomanipulation. The GCLLSG conducted a prospective phase 2 trial of NCST in 90 patients (median age, 52 years) with poor-risk CLL, defined as patients with progressive disease and at least one high-risk feature (11q–, 17p–, and/or non-mutated IGHV status and/or usage of the VH3–21 gene), refractoriness to fludarabine, or recurrent disease after autologous SCT. The conditioning regimen consisted of FC. The results of this study were reported by Dreger et al.36 Allograft with NSCT was associated with a 4-year event-free survival of 42% and an OS of 65%. Furthermore, long-term MRD-negative survival was documented in up to one-half of the patients in this trial.

Among patients with high-risk features, the younger patients having 17p abnormalities and relapsed disease represent a particularly difficult situation. In these patients, NSCT should be considered early, because responses with CIT combinations are difficult to achieve and short lasting. Stilgenbauer et al.44 have shown that alemtuzumab has activity in this subgroup, with responses obtained in 39% of the patients. A similar response rate has been reported using other novel agents such as flavopiridol.45 Unfortunately, these responses are of brief duration, lasting only 6 to 12 months. NSCT is able to induce a superior outcome in these patients. Retrospective European data reported by Schetelig et al.46 have shown encouraging outcomes in 44 patients with 17p abnormalities who underwent reduced intensity allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. The 3-year PFS was 44%. Dreger et al.36 reported the outcome of 13 patients with 17p deletion (18% of the entire study population). The OS in this group was 59% and was similar to the rest of the population, supporting the efficacy of NSCT in patients with deletion 17p.

There are currently no randomized trials reporting on the activity of NSCT compared with non-transplantation strategies, but there is evidence from the trials that we reviewed that NSCT can provide long-term disease control in patients with high-risk features. This is particularly relevant to the younger population, and the transplant option should be presented early to patients with high-risk features. The discussion should include the benefits of NSCT, the rational behind this intervention in patients with unfavorable features, the inferior outcome in patients with refractory disease, and NSCT-associated morbidity and mortality due to GVHD.

Supportive Care

Younger patients are likely to live many years with CLL, and therefore have an increased risk of developing CLL-related complications and treatment-associated effects. The majority of patients with CLL have hypogammaglobulinemia and impaired T-cell function. The routine use of immunoglobulin replacement is not recommended and should be limited to transient administration of intravenous immunoglobulins in conjunction with antibiotic treatment in selected patients with recurrent bacterial infections.47

Antibiotic, antiviral, and antifungal prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for patients with CLL. The amount of prophylaxis given to patients receiving CIT and other interventions has varied among the clinical trials. With the FCR regimen, Keating et al. routinely implemented antiviral prophylaxis with valacyclovir.15 In patients with active or recent infections undergoing CIT treatment, preemptive intervention should be implemented with the help of infectious disease experts. In patients receiving alemtuzumab, monitoring for cytomegalovirus reactivation is of paramount importance, and consideration should be given to the use of prophylactic valgancyclovir.48 Similarly, a more aggressive prophylaxis is appropriate in the setting of NSCT.

Patients with CLL who are receiving CIT and experience neutropenia should also be supported with growth factors as per standard guidelines. Because late-onset cytopenias complicate CIT and combination chemotherapy, blood-count monitoring should be performed for at least 1 year following treatment.

Patients with CLL are also at increased risk of developing other malignancies. A report from Tsimberidou et al.49 quantified the risk of a second cancer to be 2.2 times higher in patients with CLL than the expected risk based on population information. The more common cancer sites in this study were skin, prostate, and breast. It is therefore important to ensure that patients with CLL and their physicians are aware of the increased risk of other malignancies and that careful surveillance is performed.

Treatment-related myelodysplastic syndromes, acute myelogenous leukemias, and other hematological malignancies have been reported in patients with CLL who have undergone therapy with alkylating agents alone or as part of CIT combinations49 . The exact incidence of these neoplasms has not been yet defined due to a lack of long-term follow-up in some of the older studies and to insufficient observation time for the most recent trials. Tam et al. observed an actuarial risk of myelodysplasia of 2.8% at 6 years in 300 patients treated with FCR.15

Conclusions

In younger patients with CLL, the emphasis is on effective treatment and early identification of patients who are unlikely to obtain a prolonged remission. Ongoing and future prospective clinical trials that incorporate MRD monitoring, new agents, effective consolidation treatments, and prompt referral for allogeneic SCT are fundamental steps for the successful development of active strategies.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest: The author declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Alessandra Ferrajoli, MD, Department of Leukemia, Division of Cancer Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center 1515 Holcombe Blvd., Houston, TX 77030; Phone: (713) 792-2063; Fax: (713) 563-9485; e-mail: aferrajo@mdanderson.org

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Xavier Badoux for his contributions to the tables and figures of this manuscript; to Michael Keating, Stefan Faderl, Xavier Badoux, and Stephan Stilgenbauer for critical reading of the manuscript; and to Michael Keating, Peter Dreger, Stephan Stilgenbauer, Issa Khouri, and William Weirda for sharing their data.