Abstract

The use of patient-reported outcomes to measure the health and well-being of patients from their perspective has become an acceptable method to determine the impact of a disease and its treatment on patients. In patients with hemoglobinopathies, prior work has demonstrated that patients experience significant impairment in health-related quality of life (HRQL, a type of patient-reported outcome). This work has provided a better understanding of the burden that these patients experience and the factors that are associated with worse HRQL. The recent development of disease-specific HRQL instruments in sickle cell disease heralds new opportunities to explore the impact of the disease and its treatment on patients. The standards necessary to incorporate the measurement of HRQL into clinical trials are now well outlined by regulatory agencies. Measuring HRQL within a clinical practice setting and outside of the healthcare setting while the patient is at home are now possible and present new opportunities to understand the health and well-being of patients with hemoglobinopathies.

Patient-reported outcome

A patient-reported outcome (PRO) is defined as the measurement of a patient's perception of a health condition and its treatment. Examples of PROs include a patient's report of functioning, pain or other symptoms, satisfaction, and sleep quality. PRO instruments measure well-being in a structured way via the perspective of the patient or the patient's proxy. Health-related quality of life (HRQL) is a type of PRO and is the patient's report of how his/her well-being and level of functioning are affected by individual health or medical treatment received. This is in contrast to the broad concept of quality of life that is used in many disciplines, not just healthcare, that incorporates all aspects of a person's life. This review focuses on HRQL in hemoglobinopathies.

Why measure HRQL?

Determining HRQL within a target population allows for benchmarking of the disease across other populations. This provides a better understanding of the burden of disease that patients experience and is informative to providers, patients, families, and others. In addition, using HRQL to measure the impact of treatment uniquely focusing on the perspective of the patient provides opportunities to tailor therapies. Furthermore, a patient's HRQL has been shown to be a strong predictor of outcomes such as morbidity and mortality.1,2 Lastly, the use of HRQL has been shown to improve patient-provider communication and to create a more patient-centered environment.3

Instruments to measure HRQL in hemoglobinopathies

When choosing which instrument to use to measure HRQL in patients with hemoglobinopathies, several factors should be considered. In children, instruments designed for self-reporting and proxy reporting including as wide a range of ages (infant to 18 years) as possible should be considered when selecting an instrument. In addition, the use of a generic HRQL instrument will allow comparison with other populations, both healthy subjects and those with chronic disease, to aid in learning more about the burden of illness that patients experience. Finally, disease-specific instruments should be used when possible because this increases the specificity in measuring HRQL and is especially useful when looking for differences within patients with hemoglobinopathies. Most advocate using both a generic and a disease-specific HRQL instrument when assessing patients.

The HRQL instrument chosen should also demonstrate robust psychometric properties within the population under study. Generally, this includes the basic measurement properties of reliability, validity, responsiveness, and interpretability (ie, what do the HRQL scores mean?). In addition, to reduce patient burden and facilitate use in athe clinical setting, the instruments should be as brief as possible. There are numerous generic HRQL instruments that meet these criteria and can be used to measure HRQL in patients with hemoglobinopathies. Although there are numerous HRQL instruments, the most common tools that have been used in children with hemoglobinopathies are the PedsQL generic core scales and the Child Health Questionnaire. Both of these include a parent-proxy and child self-report version. Although self-reporting is considered the best method to measure HRQL, in those too ill or too young to report their HRQL, a caregiver as proxy is acceptable. In adults, the SF-36 is the most common instrument used. The SF-12 is a shorter version of the SF-36 and may also be used to assess HRQL; however, it is less precise in its measurement, which is problematic when sample sizes are small as is common in sickle cell disease (SCD) studies. The psychometric properties of the PedsQL generic core scales, the Child Health Questionnaire, and the SF-36 for use in those with SCD have been well described and strengthen the rationale for their use in this population.4–9 There are no studies outlining the psychometric properties of generic HRQL tools in patients with thalassemia.

The Adult Sickle Cell Quality of Life Measurement Information System (ASCQ-Me) HRQL instrument for adults with SCD was developed under a National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) initiative.10 Although this instrument has undergone initial field testing at clinical sites, there are no published data yet on its performance within this population. Given its known content, it is certain to add specificity to the measurement of HRQL in adults with SCD. In addition, the presumed specificity of the instrument makes it ideal to use within clinical trial settings to measure patient functioning and well-being in response to treatment.

The PedsQL SCD–specific module was also developed with the support of the NHLBI.11 Field testing of the instrument is nearly complete and will yield initial psychometric results on the validity and reliability of the instrument. In addition, an ongoing study is examining the responsiveness of the instrument (ie, can the instrument detect changes in functioning in children with SCD over time?) and shorter recall periods (ie, 1-week recall instead of 1-month recall).

The NIH supported the development of the Patient Reported Measurement Outcomes Information System (PROMIS) to measure PROs including HRQL. PROMIS includes the use of computerized adaptive testing, which tailors questions to the individual subject based upon that person's previous response using electronic measurement of HRQL, thus decreasing a patient's response burden. PROMIS is currently being tested in a cohort of patients with SCD and likely will bring new opportunities to learn more about the impact of SCD on HRQL and other PROs.12

There are some limitations to the instruments available to study HRQL in patients with hemoglobinopathies. Although the SF-36 and PedsQL modules are both widely translated, including in southeast Asia, there is limited translation of the forms in African dialects, which limits the ability to assess HRQL for hemoglobinopathies that are seen globally. HRQL can be compared across countries for those countries where instrument translations are available. However, there have been no large population studies to determine how an instrument developed in one country that has been translated for use in another country will perform and account for inherent differences in culture. The disease-specific forms are new and the psychometric properties are not yet described. In addition, there is a lack of instruments that measure HRQL across the lifespan (ie, in both children and adults), which limits the ability to compare across ages as children become adults. PROMIS is positioned to allow comparison of a patient's functioning from childhood through to adulthood, especially as more pediatric item banks that are comparable to the adult item banks are developed.

HRQL in hemoglobinopathies

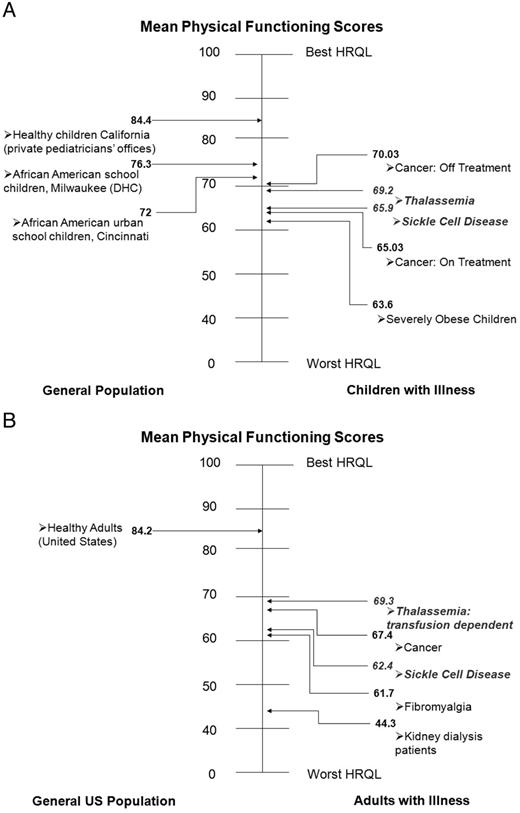

There are numerous reports that detail the HRQL of children and adults with SCD and thalassemia. Most of these focus on the baseline assessment of HRQL at one point in time and provide data on the disease burden of patients (Figure 1).

HQRL in children (A) and adults (B) with hemoglobinopathies compared with healthy populations and those with other chronic diseases.

HQRL in children (A) and adults (B) with hemoglobinopathies compared with healthy populations and those with other chronic diseases.

In SCD, it has been shown that patients have significantly impaired HRQL at baseline, which was detailed in a recent systematic review.13 Impaired HRQL is associated with disease-related symptoms such as frequent vasoocclusive painful episodes, acute chest syndrome, or stroke. In addition, patients with other medical comorbidities (the most common being asthma) or neurobehavioral comorbidities (eg, developmental delay or attention deficit disorder) have worse HRQL. In addition to these medical comorbidities, patients with SCD also face familiar demographics (eg, family income and parental education) that are associated with worse HRQL. In adults, laboratory markers of disease, such as hemoglobin, fetal hemoglobin, and lactate dehydrogenase, are associated with impaired HRQL. Understanding the underlying factors that can affect HRQL gives providers and patients additional information on modifiable factors to target to improve HRQL.

Fewer studies have been conducted in patients with thalassemia than in those with SCD. Patients with thalassemia have also been described as having significant impairments in HRQL at baseline. This is especially true in the area of general health for teens and adults. In children, HRQL has been shown to be impaired in all areas, with some data showing a more significant impact on school functioning.14 Predictors of poor HRQL in patients with thalassemia include transfusion dependence, lower family income, severe disease (defined as a need for chelation and transfusions), older age, and a greater number of secondary complications of the disease.15

Use of HRQL to measure impact of treatment and as an alternative end point within clinical trials

Impact of treatment

Thalassemia.

There have been no definitive studies to determine the impact of chelation type on HRQL or other PROs in patients with thalassemia. One small study (less than 20 patients per treatment group) examined HRQL in thalassemia patients being treated with desferrioxamine, deferiprone, or deferasirox and failed to demonstrate differences in HRQL between treatment groups.16 A larger study that assessed only desferrioxamine did report overall patient satisfaction with the treatment effectiveness, but dissatisfaction with side effects of treatment; they also reported that the treatment was burdensome. With the increased availability of oral iron chelation therapy, there is an opportunity to compare HRQL or other PROs within different iron chelation groups to better understand the impact of chelation therapy on HRQL and other PROs. However, the use of generic HRQL instruments will limit the ability to detect true differences in patients due to the nonspecific nature of the measures within thalassemia.

There are 3 studies that have examined the HRQL of thalassemia patients after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), one of which includes SCD patients. A study conducted in Hong Kong examined 27 patients after HSCT and compared their HRQL with that of 84 thalassemia patients who were transfusion dependent.17 Adult HSCT patients reported significantly better overall health, physical health, energy level, and less fatigue than those patients who remained on transfusion therapy and iron chelation therapy. The children in this study did not have significant differences in HRQL after HSCT. The second study of 19 adults reported HRQL scores without comparison, but did note that the majority of patients reported a very good HRQL overall.18 The third study, which includes 6 patients with thalassemia and 7 with SCD, compared HRQL with patients receiving HSCT for a malignancy or aplastic anemia.19 This longitudinal study assessed children‘s HRQL at baseline and at 45 days and 3, 6, and 12 months after HSCT, and demonstrated that patients recovered to baseline HRQL by 3 months after HSCT after experiencing a decrease in HRQL at 45 days after HSCT. These important data are informative for patients and families as they make decisions about whether to proceed with HSCT, and can provide decision-making support for families to understand better what to expect for their child if they choose HSCT. In addition, these data support the need to assess HRQL more immediately after HSCT (in this study, at 45 days) to capture the impact of HSCT and potential therapies on HRQL.

SCD.

As noted in the section above, there is one study reporting HRQL of SCD patients before and after HSCT. In addition, a prospective study involving patients presenting with acute painful crisis evaluated a patient's HRQL at presentation and 1 week after discharge from the hospital.20 All patients received standard treatment with pain medications and supportive care. This study illustrated that children experienced significantly impaired HRQL at presentation of an acute painful event and return to baseline HRQL 1 week after discharge. A cross-sectional study of the HRQL of children receiving hydroxyurea demonstrated better overall HRQL and better physical HRQL compared with those who were not receiving hydroxyurea.21

Use of HRQL as end points in clinical trials

Thalassemia.

The use of HRQL and other PROs within clinical trials in patients with thalassemia are rare. When www.clinicaltrials.gov was accessed in March of 2012, there were only 7 studies that incorporated HRQL as an end point to the trial. Of these, 3 studies had been completed but published results were not found, and the remaining 4 studies are open clinical trials.

SCD.

There have been a few clinical trials involving therapeutics in SCD that have reported HRQL outcomes as an end point on the trial. Only one study has been reported involving children. This study by Thornburg et al22 was a small trial of 14 children placed on hydroxyurea as part of a safety and efficacy trial. The study did not demonstrate any significant changes in HRQL over an approximately 2-year time period using a generic HRQL tool. The use of a disease-specific tool such as the PedsQL SCD module, which was recently developed in our laboratory, should increase the specificity needed to detect differences within the SCD population and differences due to a therapeutic intervention.

In adults, the multicenter study of hydroxyurea (MSH) reported improved HRQL in patients receiving hydroxyurea who were high fetal hemoglobin responders compared with patients receiving a placebo.23 In addition, they demonstrated that daily pain was predictive of a change in the patient's HRQL. One small study of 19 patients examined prospectively the impact of morphine using patient-controlled analgesia versus continuous infusion on HRQL.24 Using the SF-36 generic HRQL tool, the study reported no differences in baseline HRQL and HRQL 2 days later in this small clinical trial. Given the nonspecific nature of the generic HRQL tool used in both of these studies in addition to the very short recall period in the second study, it is not surprising that very little impact on HRQL was found. The use of a disease-specific instrument for adults, such as the SCD-specific HRQL tool ASCQ-Me,10 which is now available, should improve the ability to detect differences in HRQL within patients with SCD and between treatment groups.

A search of www.clinicaltrials.gov in March of 2012 looking for clinical trials using HRQL as an end point evealed 13 open studies that are examining HRQL as an outcome in SCD trials, which illustrates the increasing use of HRQL in the clinical trial setting.

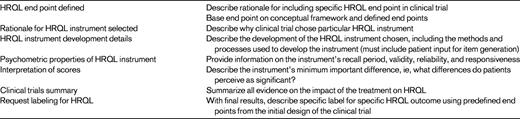

Regulatory guidelines for using HRQL (or any PRO) in clinical trials to obtain labeling

Because it is recognized by regulatory agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration that some responses to drugs involve a patient's perception, such as drugs used to treat pain, the use of HRQL to support a label claim for a drug is allowed. The use of HRQL in clinical trials allows a patient to provide their own perspective on the efficacy or effectiveness of treatments. However, the process to get HRQL on a drug's labeling claim involves several distinct guidance requirements that are put together into a dossier.25 Table 1 lists the main elements that need to be included in the dossier. For researchers involved in the utilization of HRQL within clinical trials, the recommendations listed in the table should be followed when writing clinical trial protocols and publishing data to help provide consistent evidence for future labeling potential for drugs being tested. For example, when designing a clinical trial using HRQL as an end point, the protocol should include well-defined HRQL end points and the rationale for why the specific HRQL instrument chosen was included. Furthermore, the rationale for the instrument used and documentation that the instrument has sound psychometric properties for the population under study should be documented in clinical trial protocols and subsequent publications. Lastly, the HRQL instrument chosen should have a well-described minimum important difference (MID, the minimum change in HRQL that is detectable by the patient) so that changes in HRQL can be interpreted as meaningful or not to patients enrolled on the clinical trial. Specifically, this is a change that would be considered clinically significant. Much research has been done to determine the best methods to define this change for the instruments commonly used and a detailed discussion may be found in those publications.26–32 Dissemination of this information, especially when well documented, will provide useful information for future researchers and will improve the potential for obtaining a drug labeling for HRQL.

Uses for HRQL in a clinical setting

The use of HRQL within a routine clinical setting has not been described for patients with hemoglobinopathies. However, there are several studies documenting the routine use of HRQL assessments in a clinical setting in patients with cancer33–35 and other chronic diseases. Overall, these studies have documented that using HRQL data improves patient physician communication, is acceptable to patients and providers, and aids in the care of patients with chronic illnesses. In addition, patients become more aware of their functioning and symptoms when they actively participate in providing HRQL information to their providers, and they are thus better able to advocate for themselves to improve their HRQL. Given the increased availability and use of electronic systems, capturing HRQL in a clinical setting and providing “real-time” data to care providers is now possible. This allows the provider to be able to react to changes in HRQL and to tailor treatment, especially when significant worsening of HRQL is noted from visit to visit. HRQL can also be measured outside of the clinical setting, when the patient is in their home setting, and can provide a means to track functioning over time and alert care providers to any worsening in HRQL, as was demonstrated in a cohort of patients with cancer.34 Technological advancements, including smart phone technology, should allow us to begin moving the measurement of HRQL to patients wherever they may be and to make the measurement of HRQL simple, efficient, and convenient. With the recent development of disease-specific HRQL instruments in SCD, the measurement of HRQL for clinical use to detect intrapatient changes is now a realistic goal.

Summary and future directions

Measuring HRQL in patients with hemoglobinopathies is a unique but robust way to represent the patient's voice and provides an opportunity to learn from a patient's perspective what affects his or her disease. There is enough evidence demonstrating the significant impairments in HRQL that these patients experience, especially in SCD, and future work should focus on incorporating the measurement of HRQL into all clinical trials of therapeutics and into the clinical management of patients with the ultimate goal of improving HRQL.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Julie A. Panepinto, Department of Pediatrics, Section of Hematology/Oncology/Bone Marrow Transplantation, Children's Hospital of Wisconsin/Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 Watertown Plank Rd, MFRC, Suite 3050, Milwaukee, WI 53226; Phone: 414-955-4170; Fax: 414-955-6543; e-mail: jpanepin@mcw.edu.