Abstract

The paradigm of “watch and wait” for low-tumor-burden follicular lymphoma (LTB-FL) was established in an era when the treatment options were more limited. With the introduction of rituximab, it appears that the natural history of this incurable disease has changed. However, most of the contemporary treatment data have been generated in patients with high tumor burden, and it is unclear whether the improvements in outcome also apply to the LTB population. There are no published trials evaluating rituximab-chemotherapy combinations and just a few studies evaluating single-agent rituximab in this population. As a result, there are many unknowns in the management of LTB-FL. Would the application of rituximab-chemotherapy combination cure a fraction of patients? Would the application of rituximab-chemotherapy combination improve the overall survival of the population? Would treatment with single-agent rituximab improve the psychologic quality of life by avoiding a watch and wait interval or by delaying the time to first chemotherapy? This review, a mixture of data and opinion, will discuss goals of therapy for an LTB-FL patient, summarize existing data, and propose a management algorithm.

The case

A 47-year-old man is referred to see you. He has a new diagnosis of follicular lymphoma (FL). One month before his visit with you, he had undergone a virtual colonoscopy. There was a family history of colon cancer, which precipitated the screening evaluation. Testing revealed no pathology in the colon, but did show widespread, small-volume retroperitoneal and mesenteric lymphadenopathy. Laparoscopic excision of a mesenteric lymph node revealed grade 1-2 FL.

The patient is extremely anxious at your first encounter. You establish that he has no symptoms attributable to his lymphoma. He is slightly overweight but otherwise healthy and takes only a multivitamin and baby aspirin. There is no family history of lymphoma, but his mother died from colon cancer at age 56. He works as an accountant. He is married and has 2 children, ages 14 and 12. On physical examination, you find no pathologic adenopathy or splenomegaly. His wife, who accompanies him to the visit, has done considerable internet research and is equally anxious. She hands you a stack of available clinical trials and wonders if he can have vaccine. You explain some general principles of FL and explain that a staging evaluation must be completed before any treatment decisions can be made. Over the next week, diagnostic-quality CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; a BM biopsy and routine laboratory tests are obtained. The results of his staging evaluation reveal a normal complete blood count, normal routine chemistries, normal lactate dehydrogenase, and normal β-2 microglobulin. The CT scans demonstrate pathologic paratracheal, mesenteric, retroperitoneal, and bilateral iliac chain lymphadenopathy. There is one 3.2-cm mesenteric node and all others are less than 3 cm. The BM reveals 10% involvement with FL. At his second appointment, you explain that he has stage IV, but low-tumor-burden FL (LTB-FL). What management strategy do you recommend?

Identifying candidates for W&W

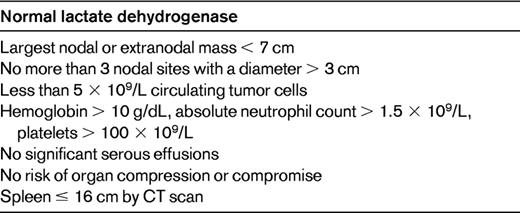

Our patient can be considered a candidate for deferred treatment, commonly called “watch and wait” (W&W). Different research groups have unique definitions for patients “requiring therapy.” It is the patients who fail to meet these criteria who are considered candidates for W&W. As a rule of thumb, patients must be asymptomatic from their lymphoma and must have a relatively low tumor burden. Commonly used for defining tumor burden are the Groupe D'Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires (GELF) criteria (Table 1).1

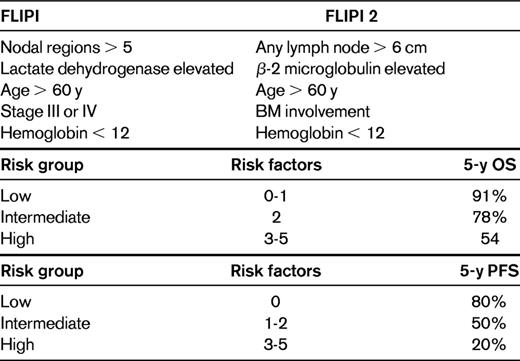

An alternative option is use of the Follicular Lymphoma Prognostic Index (FLIPI) or the FLIPI 2 (Table 2).2,3 The FLIPI is a prognostic index that was developed in patients treated in the pre-rituximab era, which can assign a patient into overall survival (OS) risk groups at the time of diagnosis. FLIPI 2 was developed in the post-rituximab era, specifically in high-tumor-burden (HTB) patients, and is prognostic for progression-free survival (PFS). Whether the FLIPI or FLIPI 2 should be used to identify patients in need of immediate therapy is unclear because the tools were not developed with that intent. Certainly there will be some overlap between low-risk FLIPI patients and LTB patients, but there are a significant proportion of discordant patients as well. For example, in E4402 (Rituximab Extended Schedule or Retreatment Trial [RESORT]), a trial designed for LTB-FL by GELF criteria, 36% of the patients were considered high risk by FLIPI.4 In practice, I find the GELF criteria more useful than FLIPI for the determination of whether to initiate therapy.

Framing the issue

According to the LymphoCare study, an observational cohort of 2728 FL patients diagnosed in the United States between 2004 and 2007, the initial therapeutic strategy was observation in 18%, single-agent rituximab in 14%, rituximab plus chemotherapy (R-chemo) in 52%, and “other” in 16%.5 LymphoCare did not separate patients by tumor burden and US practice patterns in LTB-FL are not known. Our patient is LTB by GELF criteria and low risk by FLIPI. In the rituximab era, the best initial management of LTB-FL is unclear. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines suggest that W&W is the standard.6 However, all data supporting W&W were generated in the pre-rituximab era.1,7,8 Outcomes from more recent randomized clinical trials in HTB-FL, have shown OS advantages when rituximab is combined with CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone), CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), and MCP (mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, and prednisone).9–11 This has led some to speculate that applying R-chemo strategies earlier in the disease course (ie, at the LTB phase) would lead to even better outcomes and perhaps even cures. Complicating the debate further is administering single-agent rituximab, which provides an effective, low-risk option.12–14

One has to ask the question, what is the goal? Typically, when treating cancer patients the goals are cure, improved OS, or relief of symptoms. Our patient is asymptomatic, eliminating one of the goals. In addition, we lack data indicating that immediate treatment will reliably cure such patients or improve the OS of the population. Perhaps there are other goals that should be considered in LTB-FL, such as quality of life (QOL)? Some patients are uncomfortable with W&W, so there may be a psychologic benefit for immediate treatment. If QOL were shown to be enhanced by immediate therapy, would it then be justified? Let us consider the options of W&W, R-chemo, and single-agent rituximab while keeping the goals in mind.

The case for W&W

The paradigm for no initial therapy was pioneered at Stanford University in the 1970s. Two retrospective studies strongly suggested no detriment to patients who took this approach.15,16 Three randomized clinical trials later confirmed the Stanford observations.1,7,8 LTB patients assigned to W&W enjoyed the same OS as patients who started immediately on therapy. The median time to first chemotherapy in all studies was 2.5-3 years. Based upon these observations, W&W has become a generally accepted standard of care around the world.

However, all of these studies were conducted in the pre-rituximab era and each had unique limitations. The study from the National Cancer Institute compared W&W against aggressive combined modality therapy (CMT; ProMACE-MOPP [prednisone, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etooside, mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine] plus subtotal nodal irradiation).7 Theoretically, this design of W&W versus the best-available antilymphoma therapy should maximize the likelihood of observing an OS difference. However, in this instance, one must be concerned about late toxicities and excess mortality that can arise from the CMT approach. In addition, the trial was rather small, with just 41 evaluable patients on W&W versus 45 on CMT. A major critique of the other 2 trials is that patients assigned to immediate therapy may not have received the best-available antilymphoma therapy. In the GELF trial and in the British National Lymphoma Investigation (BNLI) trial, W&W was compared against single-agent alkylator therapy (both trials) and IFN-α (GELF).1,8 Critiques aside, the fact remains that no trial has been able to demonstrate an improvement in OS when treatment is initiated in the LTB phase.

The case for R-chemo

There are no studies of R-chemo versus W&W in the published literature. In fact, this author is unaware of any ongoing or planned studies addressing this question. The case for R-chemo is essentially one of extrapolation. There are 4 published clinical trials indicating significant clinical benefit for R-chemotherapy over chemotherapy in HTB-FL.9–11,17 All of the trials found a significant PFS advantage for R-chemo, and 3 of the trials have reported a small but statistically significant OS advantage.

The extrapolation argument is as follows. When given the same therapy, LTB-FL patients will have better outcomes (PFS and OS) than HTB-FL patients.1,18 In addition, HTB-FL patients are living longer after R-chemotherapy combinations. Therefore, if LTB patients received R-chemo at diagnosis, their OS would similarly improve and perhaps a fraction of patients would be cured. A potentially informative study is S0016. This was a Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) study that enrolled more than 500 patients and compared R-CHOP with CHOP followed by I-131 tositumomab. There were no HTB eligibility criteria in this trial and undoubtedly the population is a mixture of LTB and HTB. At 5 years, more than 60% of the patients in each arm are still in their first remission.19 It begs the question, might some of these patients be cured? If yes, then perhaps the entire paradigm should change.

The case for single-agent rituximab

The logic here is quite different from the case for R-chemo. In this scenario, one is more or less conceding that FL is incurable and that OS will not be affected by early application of R-chemo. The goals are more aligned with the goals of W&W, namely that the disease is incurable and must be managed over a long period of time. Part of the management strategy is to avoid overtreatment and toxicity and preserve QOL. Because QOL can be affected negatively by chemotherapy administration, delaying or avoiding chemotherapy may have a QOL benefit for some patients.20 In addition, because disease recurrence can have negative QOL implications, the ability of rituximab to induce remission and delay recurrence may have beneficial psychologic and QOL effects.21,22

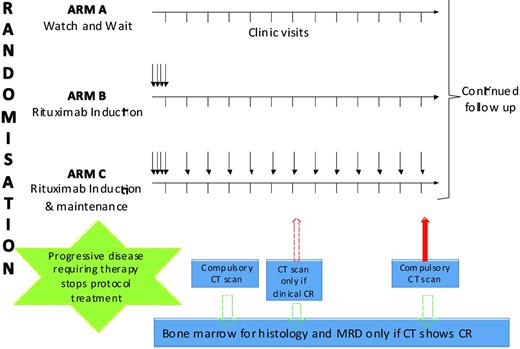

The only trial comparing any intervention with W&W in the rituximab era is a trial of W&W versus single-agent rituximab.23 This British-led intergroup study enrolled patients with advanced-stage, asymptomatic, non-bulky FL and randomized them to 1 of 3 arms (Figure 1). Patients assigned to Arm A underwent a W&W strategy. Patients assigned to Arm B received 4 weekly doses of rituximab (induction) followed by observation. Patients assigned to Arm C received induction followed by maintenance rituximab (MR; a single dose every 2 months for 2 years). The main objective of the study was to determine whether initial treatment with rituximab results in a significant delay in the initiation of chemotherapy or radiotherapy compared with the W&W approach. An important secondary objective was to determine the impact of each strategy on patient-related QOL.

Schema from United Kingdom–led trial of single-agent rituximab versus W&W.

The study enrolled 463 patients: 187 to Arm A, 84 to Arm B, and 192 to Arm C. For enrollment reasons, Arm B was closed early. The 3 arms were well balanced for important baseline characteristics. Not surprisingly, the rituximab was well tolerated, with no grade 4-5 infections. The overall response rate at 7 months was 6% (Arm A), 74% (Arm B), and 88% (Arm C), respectively. With a median follow-up of 32 months, the proportion of patients not requiring chemotherapy or radiation at 3 years was 48% in Arm A, 80% in Arm B, and 91% in Arm C (P < .001). The proportion of patients who were progression free at 3 years was 33% in Arm A, 60% in Arm B, and 81% in Arm C (P < .001). There was no difference in the OS at 3 years (95%).

The QOL data from this study have also been presented.24 Given that this population of patients are symptom free, the QOL tools focused on measuring anxiety, depression, and the adjustment to illness. The primary end point of the QOL sub-study was to determine at 7 months after randomization whether: (1) immediate treatment with rituximab results in increased functional well-being, (2) deferring treatment results in increased anxiety and depression, and (3) rituximab treatments adversely affects well-being. Additional assessments are due at months 13, 25, and 37. The initial report of the QOL made several interesting observations: (1) the majority of the patients did not suffer from anxiety or depression and the physical, social, and functional QOL was high; (2) despite statement #1, anxiety (13% vs 3%, respectively) and depression (3% vs 1%, respectively) were more common in this population than in the general population; (3) all 3 groups of patients (Arms A, B, and C) were psychologically adapted to their illness and the negative impact of the diagnosis lessened over time; (4) over time, patients assigned to rituximab had less anxiety than the patients on W&W; and (5) there was no negative QOL effect associated with receiving rituximab.

How does one interpret and integrate the data from this important study? Should all patients receive rituximab upfront? Should no patients receive rituximab upfront? Here are my conclusions. First, given the absence of an OS difference between W&W and immediate treatment with rituximab, it remains perfectly acceptable to use W&W. Second, there are some benefits associated with immediate rituximab therapy, such as improved disease free survival and a longer time to first chemotherapy. These benefits should be discussed with patients. Third, for a minority of patients, anxiety and the ability to cope with the disease is improved significantly by rituximab treatments. A candid discussion with each new patient to attempt to ascertain anxiety level and coping ability is warranted. Fourth, based upon the outcomes of these discussions, some patients are better served by rituximab administration than by W&W.

One of interesting observations from the Ardeshna study8 is the excellent outcome achieved in Arm B (induction rituximab, no MR), which closed early. Patients assigned to Arm B were almost as likely as the MR patients to be free of chemotherapy or radiation at 3 years (80% vs 91%, respectively). If one opts for single-agent rituximab in this patient population, which dosing strategy should be used? This dosing question was the subject of study in the RESORT (E4402) trial.

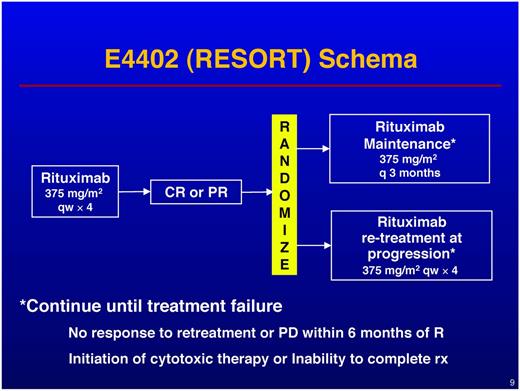

RESORT enrolled patients with LTB indolent lymphoma (GELF criteria) and treated all patients with 4 weekly doses of rituximab. Patients achieving either partial or complete remissions were then randomized to either observation with rituximab retreatment (RR) at the time of progression or MR (Figure 2). Retreatment was repeated indefinitely until treatment failure; maintenance was administered as a single dose every 3 months until treatment failure. Treatment failure was defined as: (1) development of rituximab resistance, (2) initiation of alternative therapy, and (3) inability to complete planned therapy. The primary end point of the study was to compare the time to treatment failure between the MR and the RR arms. Secondary end points were to compare the time to first cytotoxic chemotherapy, QOL, and toxicities between the 2 treatment arms. Although RESORT enrolled patients with all types of indolent lymphomas, the study was statistically designed to focus on the FL patients. Patients with other histologies were enrolled to generate a hypothesis for more definitive trials.25

Results in the FL patients were presented at the 2011 ASH meeting.4 Of the 384 patients enrolled with FL, 274 (71%) responded to the rituximab × 4 induction and were therefore randomized. The RR (n = 134) and MR (n = 140) patients were well balanced for baseline characteristics. With a median follow-up of 3.8 years, there was no difference in the time to treatment failure between RR and MR. There was a statistically significant difference in the time to first cytotoxic chemotherapy at 3 years (95% for MR vs 86% for RR, P = .03). Although the QOL analysis is preliminary, to date, no QOL difference has emerged for the 2 arms. Toxicities were minimal on both arms, although there was one case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy on MR. There is no difference in OS between RR and MR. When analyzing the results from the standpoint of resource use, the RR patients received an average of 4.5 doses of rituximab while on study, wherease the MR patients received an average of 15.8 doses. To summarized the RESORT findings: (1) RR was as effective as MR for the end point of time to treatment failure; (2) MR was slightly superior to RR for the end point of time to first chemotherapy; and (3) MR patients received, on average, 3.5 times more rituximab than RR patients.

The conclusions from RESORT were that, given the excellent outcomes with the RR strategy (86% chemotherapy free at 3 years), the lack of QOL differences between the 2 strategies, and the fewer number of rituximab doses needed, RR is the preferred strategy if opting for single-agent rituximab in LTB-FL.

What should you do the next time you encounter a LTB-FL patient in clinic?

My view is that patients should be encouraged to begin on a course of W&W. I say this because we still lack data indicating an OS benefit for immediate treatment. This approach is highly counterintuitive to most patients and the discussion is generally a long one. What about immediate treatment to improve QOL? The Ardeshna data suggest that there are some QOL benefits that come from immediate treatment with rituximab. However, closer inspection of the data suggests that it is a minority of patients (approximately 15%) who suffer from substantial anxiety related to the diagnosis. The data also indicate that most patients adapt to their diagnosis and to the notion of W&W.24

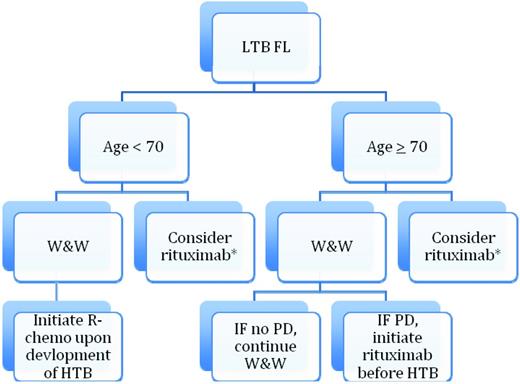

The Ardeshna QOL is consistent with my own experience, in which most patients, if properly informed, can become comfortable with W&W. However, there is a subset of patients (perhaps 10%-20%) who cannot and for whom the W&W process has a significant negative effect on their QOL. For those patients, I believe that single-agent rituximab is a reasonable approach and, if opting for rituximab, the RESORT data suggest that a retreatment dosing strategy produces excellent outcomes and saves resources. There is one other scenario in which I will recommend single-agent rituximab to a patient with LTB-FL. Suppose a patient over age 70 comes in with a new diagnosis of LTB-FL. After an appropriate discussion, I will recommend a strategy of W&W. Some of these patients (20%-40%) have essentially no progression after many years.8 This means that 60%-80% will progress toward HTB and a need for R-chemo. Given the toxicities and difficulties associated with R-chemo in older patients, I will often initiate treatment with single-agent rituximab before they reach the HTB stage. My goal for that patient is to avoid cytotoxic chemotherapy in their lifetime. Therefore, W&W and treatment with single-agent rituximab in a LTB-FL patient are not necessarily mutually exclusive. A suggested management algorithm is provided in Figure 3.

Suggested algorithm for management of LTB-FL. This algorithm is for the scenario in which W&W has a detrimental effect on QOL (< 15% of patients). PD indicates progressive disease.

Suggested algorithm for management of LTB-FL. This algorithm is for the scenario in which W&W has a detrimental effect on QOL (< 15% of patients). PD indicates progressive disease.

Conclusions

W&W is alive and well, even in the rituximab era. In a way, this is disappointing. Wouldn't it be nice to know that immediate treatment has a positive effect on outcomes? This would indicate progress. However, until a trial comparing W&W and R-chemo with an OS end point and 15 years of follow-up is published, we will continue to practice in a world filled with uncertainty. Because such a trial is neither under way nor planned at this time, we need to do the best we can with what we have (inadequate data plus experience). Newly diagnosed LTB-FL patients deserve a thoughtful conversation with a discussion of goals and expected outcomes with management strategy. After such a discussion, most (but not all) patients will become comfortable with W&W. Therefore, in practice, a certain degree of individualization is appropriate. Given the inadequate state of knowledge, LTB-FL patients should continue to be the subject of study in clinical trials.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has consulted for Astellas, Celgene, Cell Therapeutics, Cephalon, Genentech/Roche, Gilead, and GSK and has received research funding from Abbott, Cephalon, Genentech, Gilead, Infinity, and Pharmacyclics. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Brad Kahl, MD, University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, 1111 Highland Ave, 4059 WIMR, Madison, WI 53705; Phone: 608-263-1836; Fax: 608-262-4598; e-mail: bsk@medicine.wisc.edu.