Abstract

The new oral anticoagulants are rapidly replacing warfarin for several indications. In contrast to warfarin, which lowers the functional levels of all of the vitamin K-dependent clotting factors, the new agents target either factor Xa or thrombin. With targeted inhibition of coagulation, the new oral anticoagulants have pharmacologic and clinical features that distinguish them from warfarin. Focusing on these features, this paper (a) compares the pharmacology of the new oral anticoagulants with that of warfarin (b) identifies the class effects of these drugs and their differentiating features, (c) reviews their current indications, and (d) uses this information to help clinicians make informed decisions regarding the choice of the right anticoagulant for the right patient.

Introduction

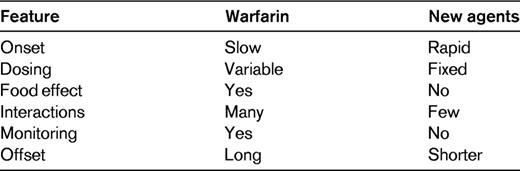

Oral anticoagulants are widely used for long-term prevention or treatment of thrombosis. Until recently, the only available oral anticoagulants were the vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin. In the past few years, however, the landscape has changed with the introduction of new oral anticoagulants that specifically target either factor Xa or thrombin.1 These new agents have several advantages over warfarin (Table 1); food does not influence their metabolism, drug-drug interactions are uncommon and the agents produce such a predictable anticoagulant effect that they can be given in fixed doses without the need for routine coagulation laboratory monitoring. Consequently, the new anticoagulants are more convenient to administer than warfarin. Furthermore, not only are they as effective as warfarin, but the new agents also cause less intracranial bleeding.2–4

Although the new oral anticoagulants have many features in common, and are often considered as a new class of drugs, there are some differences.1 These distinctions need to be considered when personalizing the approach to anticoagulation therapy for each patient. Focusing on the similarities and differences among the new oral anticoagulants that are licensed or under consideration for licensing, this paper (a) compares the pharmacology of the new oral anticoagulants with that of warfarin, highlighting key differences amongst the new agents (b) identifies what we have learned about the new oral anticoagulants from clinical trials where they were compared with warfarin, pointing out the class effects and the differentiating features, (c) reviews the current indications for the new oral anticoagulants, and (d) uses this information to help clinicians make informed decisions regarding the choice of the right anticoagulant for the right patient.

Pharmacologic comparisons with warfarin

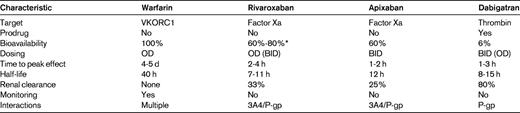

The properties of the new oral anticoagulants are distinct from those of warfarin (Table 2). Thus, the new agents are direct anticoagulants that target a single clotting enzyme, either factor Xa or thrombin, thereby inhibiting thrombin generation or thrombin activity. In contrast, warfarin is an indirect anticoagulant with multiple targets. Thus, warfarin has no intrinsic activity, but rather acts as an anticoagulant by lowering the functional levels of the vitamin K-dependent procoagulant proteins; prothrombin and factors VII, IX and X, as well as the vitamin K-dependent anticoagulant proteins; proteins C, S and Z.

Comparative pharmacology

BID indicates twice daily; OD, once daily; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; VKORC1, C1 subunit of the vitamin K epoxide reductase enzyme; 3A4, cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme.

*Bioavailability of rivaroxaban decreases as the dose is increased because of poor drug solubility; with OD doses of 20 and 10 mg, the bioavailabilities are 60% and 80%, respectively.

Rivaroxaban and apixaban, the oral factor Xa inhibitors, are active compounds with an oral bioavailability of more than 50% (Table 2). They have a rapid onset of action with maximum plasma concentrations achieved 1 to 4 hours after oral administration. In contrast, dabigatran etexilate, the oral thrombin inhibitor, is a prodrug that requires metabolic activation. However, it also has a rapid onset of action; dabigatran concentrations peak in plasma 1 to 2 hours after oral administration.

Unlike the direct anticoagulants, warfarin has a slow onset of action because it takes several days to lower the functional levels of the vitamin K-dependent procoagulant factors into the therapeutic range. Consequently, warfarin must be overlapped with rapidly acting parenteral anticoagulants for at least 5 days when initiating treatment in patients with established thrombosis or at high risk for thrombosis. In contrast, because of their rapid onset of action, such overlap is generally unnecessary with the new oral anticoagulants. Obviating the need for parenteral anticoagulant bridging streamlines therapy.

All of the new oral anticoagulants are cleared to some extent by the kidneys. However, the extent of renal clearance is an important differentiator among the agents. Thus, whereas 80% of active dabigatran is excreted in the urine, only 33% of rivaroxaban and 25% of apixaban are cleared as unchanged drugs. Because of renal clearance of unchanged drug, there is a potential for drug accumulation in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min). This potential is greater for dabigatran than it is for the oral factor Xa inhibitors. In contrast to the new agents, the pharmacologic effect of warfarin is unaffected by renal impairment because only inactive warfarin metabolites are cleared via this route.

Many drugs enhance or reduce the anticoagulant effects of warfarin. In addition, common genetic polymorphisms and dietary vitamin K intake influence the metabolism and pharmacodynamics of warfarin, thereby increasing or decreasing the dose requirements. Because of these factors, frequent coagulation laboratory monitoring is required to ensure that a therapeutic anticoagulant response is obtained. In contrast, dietary vitamin K intake has no effect on the metabolism of the new oral anticoagulants and there are few drug-drug interactions. Consequently, all of the new agents are more convenient to administer because they can be given in fixed doses without laboratory monitoring.

Selection among the new oral anticoagulants can be influenced by differences in the pharmacologic properties of the drug and the clinical trial data. Is there evidence from clinical trials that one drug is better than another?

Lessons from clinical trials

The new oral anticoagulants have been compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation2–4 and for treatment of venous thromboembolism.5–7 All of these trials were designed to show noninferiority of the new agents relative to warfarin. Most of the information we have learned about the new agents comes from the studies in atrial fibrillation because these trials were larger, and they enrolled older patients who were at higher risk for both thromboembolic events and bleeding. However, consistent results were also obtained in the venous thromboembolism treatment studies, thereby supporting the validity of the conclusions.

What have the clinical trials taught us? We see both class effects in the comparisons of the new oral anticoagulants with warfarin, as well as features that differentiate the new agents (Table 3). Each of these will be discussed separately.

Class effects

The results of the clinical trials with the new oral anticoagulants tested thus far in patients with atrial fibrillation have several features in common. First, dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban have all been shown to be robustly noninferior to warfarin for prevention of stroke (both ischemic and hemorrhagic) or systemic embolism. Second, all 3 of the new oral anticoagulants were associated with less intracranial bleeding than warfarin, and the rates of major bleeding were similar or lower than those with warfarin. The reduction in intracranial bleeding relative to warfarin is observed regardless of the time in therapeutic range with warfarin. Thus, even in centers with the best international normalized ratio (INR) management, the risk of intracranial hemorrhage was lower with the new oral anticoagulants than it was with warfarin. Third, there was a proportionally similar, approximately 10% reduction in mortality with the new oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin. Fourth, there was no evidence of hepatic toxicity with any of the new agents, which was an important safety consideration after the experience with ximelagatran.8 Therefore, we now have evidence that fixed-dose unmonitored anticoagulant therapy is at least as effective as well-controlled warfarin and is associated with less intracranial bleeding, the most feared complication of anticoagulant therapy.

Similar results were obtained when dabigatran or rivaroxaban was compared with warfarin for treatment of patients with venous thromboembolism.5–7 Both agents were noninferior to warfarin for prevention of recurrent venous thrombosis and were associated with less bleeding. Thus, with dabigatran there was a significant reduction in any bleeding, the composite of major plus clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding,5 while rivaroxaban was associated with significantly less major bleeding; at least in patients with pulmonary embolism.7 However, there were important differences in trial design. Thus, the trials with dabigatran were double-blind and included patients with either deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. In both trials, patients were randomized to receive either dabigatran or warfarin after initial treatment with a parenteral anticoagulant; heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin or fondaparinux. By contrast, 2 open-label studies were performed with rivaroxaban; one in patients with deep vein thrombosis without overt evidence of pulmonary embolism and the other in patients with documented pulmonary embolism. Patients entered in these trials were randomized to rivaroxaban, which was given in twice-daily doses for 3 weeks and once-daily thereafter, or to conventional anticoagulation therapy, wherein patients were started on a parenteral anticoagulant and then transitioned to warfarin. The ongoing double-blind trial with apixaban includes patients with either deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism and compares monotherapy with apixaban with conventional anticoagulation therapy. Apixaban is administered twice daily throughout the trial, but a higher dose is used for the first week.

Differentiating effects

What are the features that differentiate the new oral anticoagulants? First, the rate of myocardial infarction appears to be slightly higher with dabigatran than with warfarin.2,9,10 It is unlikely that dabigatran causes myocardial infarction because the rate of myocardial infarction was similar when dabigatran was compared with placebo. Instead, it is more likely that dabigatran is less effective than warfarin for prevention of myocardial infarction.11 Second, there is more gastrointestinal bleeding with both dabigatran (at least with the 150 mg twice-daily dose) and rivaroxaban than with warfarin,2,3 particularly in the elderly.12 Although this phenomenon was not seen with apixaban,4 it is interesting to note that in a comparison of rates of bleeding from various sites, the least difference between apixaban and warfarin is in the rates of gastrointestinal bleeding. Third, the higher dose dabigatran etexilate regimen (150 mg twice daily) not only reduced the rate of hemorrhagic stroke (number needed to treat to prevent one hemorrhagic stroke is 182), but also reduced the rate of ischemic stroke compared with warfarin2 ;the number needed to treat with dabigatran to prevent one ischemic stroke is 132. The failure of the other new oral anticoagulants to reduce the risk of ischemic stroke does not detract from their benefits, however, because warfarin is very effective for prevention of ischemic stroke. Fourth, apixaban is the only one of the new oral anticoagulants to be associated not only with a reduction in stroke (both ischemic and hemorrhagic, but driven only by a reduction in hemorrhagic stroke) or systemic embolism compared with warfarin, but also with less major bleeding4 ; numbers needed to treat to prevent one hemorrhagic stroke or one major bleed with apixaban compared with warfarin are 238 and 67, respectively. Although when administered at a dose of 110 mg twice daily, dabigatran also was associated with significantly less intracranial bleeding and major bleeding than warfarin (numbers needed to treat to prevent one hemorrhagic stroke or one major bleed are 192 and 77, respectively), this regimen was noninferior, but not superior, to warfarin for prevention of stroke or systemic embolism.2

As outlined below, the extensive phase III clinical trial programs with the new oral anticoagulants has led to their licensing in the United States and elsewhere for an expanding number of indications.

Current indications for the new oral anticoagulants

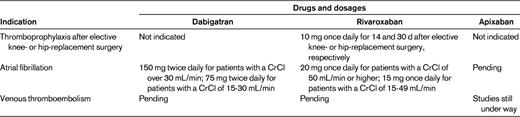

The indications for the new oral anticoagulants in the United States and the licensed doses are summarized in Table 4. In the United States, Europe, Canada and many other countries, dabigatran and rivaroxaban are licensed as alternatives to warfarin for prevention of stroke or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. It is likely that apixaban will soon be licensed for this indication and it is possible that apixaban may also be approved as an alternative to aspirin in atrial fibrillation patients who are unable or unwilling to take warfarin. However, there are country-specific differences in the licensed doses of dabigatran and the in the use of dabigatran and rivaroxaban in patients with a creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min. In the United States, the 150 mg twice-daily dose regimen of dabigatran is licensed for all patients with a creatinine clearance more than 30 mL/min, whereas a dose of 75 mg twice daily is approved for patients with a creatinine clearance of 15 to 30 mL/min. The latter dose regimen was selected based on pharmacokinetic data indicating that it yields drug exposures in patients with impaired renal function similar to those produced by the 150 mg twice-daily regimen in patients with normal renal function. In contrast, in all other countries, dabigatran is contraindicated in those with a creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min. The 110 mg twice-daily dabigatran regimen is approved in all countries except the United States and is the dose recommended for those 75 to 80 years of age or older, and for patients at risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. For rivaroxaban, the 20 mg once-daily dose is licensed in the United States, Europe and Canada for patients with a creatinine clearance of 50 mL/min or higher, whereas a dose of 15 mg once-daily is approved in the United States for those with a creatinine clearance of 15 to 49 mL/min. In contrast, in all other countries, the 15 mg once-daily dose of rivaroxaban is restricted to patients with a creatinine clearance of 30 to 49 mL/min and the drug is not recommended in those with a creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min.

Licensed indications for the new oral anticoagulants in the United States

CrCl indicates creatinine clearance.

In the United States, Europe and Canada rivaroxaban is licensed for thromboprophylaxis after elective hip or knee replacement surgery. Although dabigatran and apixaban also are licensed for this indication in Europe and Canada, this is not the case in the United States. Likewise, rivaroxaban is licensed in Europe and Canada for treatment of deep vein thrombosis, but not yet in the United States. Finally, based on the results of the ATLAS-2 trial,13 rivaroxaban is likely to be licensed as an adjunct to antiplatelet therapy to prevent recurrent ischemic events in patients with stabilized acute coronary syndrome.

With the availability of several new oral anticoagulants and the expanding list of licensed indications, how do we choose the right drug for the right patient?

Personalizing the choice of new anticoagulants

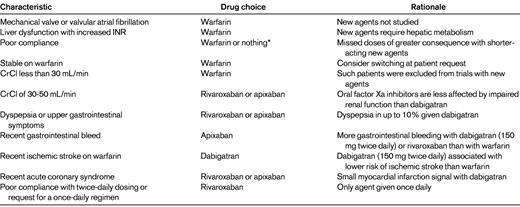

An approach to personalizing anticoagulant therapy is summarized in Table 5. When faced with a patient who requires long-term oral anticoagulant therapy, the first step is to determine whether the patient is a candidate for one of the new oral agents or is better suited for warfarin. Patients who are stable on warfarin and whose INR values are mostly in the therapeutic range need not be switched. In fact, there is mounting evidence that the frequency of INR testing can be reduced to once every 12 weeks without compromising safety in patients who are stable on warfarin.14 Moreover, there often is a level of comfort with warfarin because of long-term familiarity with its use and the capacity to reverse its anticoagulant effects, if necessary, with vitamin K, plasma and/or prothrombin complex concentrates. In contrast, the lack of a specific antidote for any of the new oral anticoagulants can be a deterrent for both patients and physicians. Although the risk of intracranial bleeding is lower with the new agents than with warfarin, this feature alone does not warrant a change unless the patient so wishes and can afford the new drug because the numbers needed to treat to prevent one hemorrhagic stroke with dabigatran (at the 150 mg twice-daily dose), rivaroxaban or apixaban are 182, 333 and 238, respectively.

Choice of anticoagulant based on patient characteristics

CrCl indicates creatinine clearance.

*For some patients who are not adherent to instructions, the risk of any anticoagulant therapy may outweigh any benefits

Patients who are noncompliant with warfarin should not be switched to the new agents because missed doses of these short acting anticoagulants have the potential to be more detrimental than missed doses of warfarin, which has a half-life of several days. Dabigatran and apixaban require twice-daily administration. Patients who prefer once-daily drugs, or are poorly compliant with twice-daily dosing regimens, can be prescribed rivaroxaban.

Patients with valvular atrial fibrillation or those with mechanical heart valves should receive warfarin because such patients were excluded from the clinical trials conducted to-date with the new oral anticoagulants. Likewise patients with hepatic dysfunction, particularly those whose baseline INR is prolonged, should not be given the new anticoagulants because all of the agents undergo some degree of hepatic metabolism. Patients with a creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min also are poor candidates for the new oral anticoagulants. Because such patients were excluded from the clinical trials, the efficacy and safety of the new agents in this population is unknown and no information is available regarding the risk-to-benefit profile of the 75 mg twice-daily dose of dabigatran. Even patients with a creatinine clearance of 30-40 mL/min may not be ideal candidates for the new oral anticoagulants; if the agents are used in such patients, rivaroxaban or apixaban may be better choices than dabigatran because the degree of renal excretion for the factor Xa inhibitors is less than that for dabigatran. When new oral anticoagulants are prescribed for patients with reduced creatinine clearance, renal function should be assessed every 3 to 4 months to ensure that the creatinine clearance remains above 30 mL/min; even those with a creatinine clearance above 50 mL/min at baseline should have their renal function monitored on a yearly basis.

Certain patient characteristics may render one of the new agents a better choice than another. For example, patients with dyspepsia or other upper gastrointestinal reports may do better with rivaroxaban or apixaban than with dabigatran because dyspepsia occurs in up to 10% of patients given dabigatran and can lead to early discontinuation. In contrast, dyspepsia is an uncommon symptom with the oral factor Xa inhibitors.

Gastrointestinal bleeding is more common with dabigatran (at the 150 mg twice-daily dose) and rivaroxaban than with warfarin, particularly in those over the age of 75 years. For this reason, the 110 mg twice-daily dose of dabigatran is recommended for the elderly; with this lower dose of dabigatran, the rate of extra-cranial bleeding in those over the age of 75 years was similar to that with warfarin.12 Because this dose of dabigatran is not licensed in the United States, apixaban may be a better choice than either dabigatran or rivaroxaban for patients with a recent history of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Because of the myocardial infarction signal with dabigatran, oral factor Xa inhibitors may be a better choice for patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. In patients who have suffered an ischemic stroke despite warfarin therapy, dabigatran may be the best choice because when given at a dose of 150 mg twice daily, dabigatran was the only one of the new agents to be associated with a lower rate of ischemic stroke compared with warfarin. Patients at low risk for stroke may be better suited for dabigatran or apixaban than for rivaroxaban because such patients were not included in the ROCKET-AF trial. Although it is likely that rivaroxaban would produce a similar risk reduction in such patients as it did in higher risk patients, the benefit-to-risk profile of rivaroxaban in low risk atrial fibrillation patients is unknown. In contrast, patients with multiple risk factors or with a history of prior stroke may be good candidates for rivaroxaban because most of the patients included in the ROCKET-AF trial had these features. Rivaroxaban is also the only agent available for patients who are poorly compliant with twice-daily dosing regimens or who request a once-daily drug. Although rivaroxaban doses more than 10 mg daily should be taken with food to improve absorption, the drug can be taken with the morning or evening meal.

Conclusions and future directions

In summary, the new oral anticoagulants represent a giant step forward in the quest to replace warfarin. In addition to their enhanced convenience, the new agents are not only safer than warfarin because of the reduced risk of intracranial bleeding, but they also have the potential to be more effective. This is particularly true in the community setting where the INR control with warfarin is poorer than that in clinical trials.

Dabigatran and rivaroxaban are already licensed as alternatives to warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation and apixaban is likely to soon follow. With the availability of more and more of these new agents, clinicians will need to decide which one to choose. The data with all of these agents provide convincing evidence of their efficacy and safety. Differences in study design, characteristics of the patients enrolled, and quality of warfarin management render cross study comparisons problematic. Consequently, in the absence of head-to-head trials, it is impossible to say that one drug is better than another. Until such trials are done, therefore, it is likely that the unique pharmacologic properties and the differences among the agents that have arisen from the clinical trials will drive the decision as to which of the new agents to choose.

Acknowledgments

J.I.W. holds the Canada Research Chair (Tier I) in Thrombosis and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario/J. Fraser Mustard Chair in Cardiovascular Research at McMaster University.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.I.W. has consulted for Bristol- Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, Bayer, and Boehringer Ingelheim; has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Johnson & Johnson. P.L.G. has received honoraria from Pfizer, Bayer, and Leo. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Dr Jeffrey Weitz, Thrombosis & Atherosclerosis Research Institute, 237 Barton St E, Hamilton, ON, L8L 2X2 Canada; Phone: 905-574-8550; Fax: 905-575-2646; e-mail: weitzj@taari.ca.