Abstract

Investigation of a patient with possible von Willebrand disease (VWD) includes a range of phenotypic analyses. Often, this is sufficient to discern disease type, and this will suggest relevant treatment. However, for some patients, phenotypic analysis does not sufficiently explain the patient’s disorder, and for this group, genetic analysis can aid diagnosis of disease type. Polymerase chain reaction and Sanger sequencing have been mainstays of genetic analysis for several years. More recently, next-generation sequencing has become available, with the advantage that several genes can be simultaneously analyzed where necessary, eg, for discrimination of possible type 2N VWD or mild hemophilia A. Additionally, several techniques can now identify deletions/duplications of an exon or more that result in VWD including multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification and microarray analysis. Algorithms based on next-generation sequencing data can also identify missing or duplicated regions. These newer techniques enable causative von Willebrand factor defects to be identified in more patients than previously, aiding in a specific VWD diagnosis. Genetic analysis can also be helpful in the discrimination between type 2B and platelet-type VWD and in prenatal diagnosis for families with type 3.

Learning Objectives

VWD displays a wide range of different phenotypes resulting from mutation to its several different domains

VWD inheritance pattern can be dominant, codominant, or recessive dependent on the contribution of different mutations to phenotype

Introduction

von Willebrand disease (VWD) is the most commonly diagnosed autosomally inherited bleeding disorder. It affects ∼1 in 10 000 individuals sufficiently to be referred to a tertiary care center.1 von Willebrand factor (VWF) is a very large multimeric glycoprotein2 that performs 2 essential hemostatic functions; it provides a means to bind platelets at sites of vascular damage and at high shear stress supports platelet aggregation. It also carries and protects coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) in the circulation, delivering it to sites of vascular injury.

Initial analysis for possible VWD examines bleeding symptoms in the patient and their family, and this typically includes epistaxis, easy bruising, and other hemorrhagic symptoms. A bleeding score (BS) system has been defined and can help predict outcomes and replacement therapy.3 Laboratory testing of quantity and activity parameters for VWF then determine whether they deviate from the normal range. VWD is divided into 3 main categories: type 1 VWD (VWD1) is a partial quantitative deficiency, and VWD3 is an almost complete quantitative deficiency of VWF. VWD2 is categorized into 4 types: 2A, 2B, 2M, and 2N, dependent on VWF function perturbed by mutation.

Recently, guidelines on the diagnosis and management of VWD have recommended that cutoff values are used in the diagnostic pathway. These suggest that patients having VWF activity levels ≥30 or 35 IU/dL should be classified as having “low VWF” in recognition that this can be a risk factor for bleeding rather than being given a VWD diagnosis.4,5

For many patients diagnosed with VWD, laboratory phenotypic assays readily suggest VWD type in the individual, enabling the clinical team to select the most relevant management for that disease type. However, where this is not the case, genetic analysis can help understand the patient’s disorder through identification of the causative mutation(s). For many years, polymerase chain reaction and Sanger sequencing were used to identify mutations in the VWF gene (VWF), but more recently, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has been introduced to diagnostic and research institutions. This technology enables simultaneous parallel sequencing of many genes. Large deletions and duplications of an exon or more can be sought using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification or microarray specific for VWF or through analysis of NGS data using an algorithm to seek missing or duplicated regions.

This article summarizes the mutation classes and their inheritance patterns associated with the different VWD types and how this information can be useful in provision of the most relevant patient management.

Type 1 VWD

This is the most prevalent VWD type in most populations, with proportions of patients up to 70% in some studies. VWD1 patients have VWF antigen (VWF:Ag) and VWF activity assays with an activity/antigen ratio >0.7 and normal VWF multimers. VWF activity can be determined using ristocetin cofactor (VWF:RCo), which measures binding to GpIb, whereas VWF:CB measures binding to collagen. New assays assess binding to engineered GpIb fragments and are collectively referred to as VWF activity determinations.6 Recent recommendations of using lower cutoff values for inclusion of these patients among those with VWD (30 or 35 IU/dL) will reduce the proportion of individuals classified as affected by VWD1.7,8 For those within this borderline group, the strongest predictors of VWD diagnosis are reduced VWF:RCo in platelet aggregation, especially in those with non–O blood group and female sex.9

Mutations are located throughout VWF from the promoter region10 to exon 52,11,12 and the majority are missense mutations (75%), whereas splice, deletion, nonsense, insertion, duplication, and large in-frame deletions mutations comprise minor proportions (Table 1).13 Most patients have dominantly inherited disease resulting from a single mutation, whereas a smaller proportion (∼5-10%) have >1 mutation contributing to their symptoms, some with recessive inheritance.14-16 Blood group O is present in up to ∼65% of VWD1.11

The predominant mechanism responsible is intracellular retention of mutant VWF, resulting in reduced secretion into plasma.17 Rapid VWF clearance from the circulation also contributes,18 with the VWF half-life in unaffected individuals being ∼8 to 12 hours and individuals with ABO blood group O having shorter half-lives. The ratio between VWF propeptide (VWFpp D1 and D2 domains) and VWF:Ag can be exploited to highlight rapid clearance, with the “Vicenza” mutation p.Arg1205His exemplifying this phenotype. The VWF half-life following desmopressin administration was ∼10% that of Haemate P. Modeling mathematically the synthesis, clearance, and cleavage of p.Arg1205His using a 1/10th half-life relative to normal VWF replicated the mutation features of low VWF level, ultralarge multimers, and reduced satellite bands.19 Rapid clearance can result in desmopressin not providing sufficiently sustained VWF elevation for longer clinical procedures; VWFpp/VWF:Ag measurement or genetic analysis can identify the cause.

In contrast to VWD types 2A, 2B, and 2M, where most heterozygous mutations are fully penetrant (all individuals with the mutation have disease symptoms), approximately half of VWD1 families have incomplete penetrance (only some individuals with a mutation have symptoms). ABO blood group contributes to reduced VWF:Ag level, and this is exemplified by the common variant p.Tyr1584Cys.20

The main use for genetic analysis in VWD1 is to help understand the cause of the more severe presentations and inheritance risk for family members.

Other genes that contribute to variation in VWF level

The Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genome Epidemiology Consortium combined analysis of 5 community-based studies (23 608 participants with European ancestry) to seek genome-wide single nucleotide variant associations with F7, F8, and VWF genes. In addition to VWF and ABO, variants in 5 further genes were identified that influenced both VWF and FVIII levels: STXBP5, SCARA5, STAB2, TC2N, and CLEC4M. Type 1, but not type 2, patient analysis in the Willebrand in Netherlands study demonstrated association of STXBP5 with a VWF:Ag level reduction of −3.0 IU/dL per allele and CLEC4M with a VWF:Ag level of −4.3 IU/dL and VWF activity of −5.75 IU/dL per allele.21 ABO blood group is associated with up to ∼25% variation in VWF levels between blood group O and non–O blood group.

Type 2 VWD

Type 2A VWD

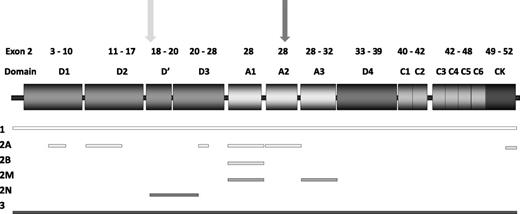

This is the largest grouping among VWD2, and includes several different disease mechanisms resulting from mutations in diverse VWF domains (Figure 1). All have high-molecular-weight multimer (HMWM) loss, but demonstrate differing multimer profiles.22 Most patients have reduced VWF activity/VWF:Ag ratios. A tertiary category for VWD2A includes mutations in the most common locations: the A2 domain (IIA), D3 domain (IIE), D2 domain (IIC), and CK domains (IID).23

Structure of VWF, highlighting mutation location. Exons encoding specific VWF domains are highlighted above the VWF domain structure. Shaded rectangles indicate VWF domains. Mutation locations are denoted by shaded bars indicating regions associated with each VWD type. Furin (light gray) and ADAMTS13 cleavage sites (dark gray) are indicated by arrows.

Structure of VWF, highlighting mutation location. Exons encoding specific VWF domains are highlighted above the VWF domain structure. Shaded rectangles indicate VWF domains. Mutation locations are denoted by shaded bars indicating regions associated with each VWD type. Furin (light gray) and ADAMTS13 cleavage sites (dark gray) are indicated by arrows.

Summary of mutation location for VWD patients reported on the VWF mutation database

| VWD type . | VWF domain . | Mutation location . | Inheritance pattern . | Phenotype . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | All | Promoter-ex52 | Majority dominant, minority >1 mutation or recessive | VWF activity/VWF:Ag >0.7 |

| 2A/IIC | D2 | Ex11-16 | Recessive | Mostly very discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag |

| 2A/IIE | D3 | Ex22 & 25-28 | Dominant | Discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag, most <0.6 |

| 2A | A1 | Ex28 | Dominant | Discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag |

| 2A/IIA | A2 | Ex28 | Dominant | Discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag |

| 2A/IID | CK | Ex51-52 | Dominant | Discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag |

| 2B | A1 | Ex28 | Dominant | Wide range of VWF activity/VWF:Ag possible |

| 2M | A1 | Ex28 | Dominant | Discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag and/or VWF:CB/VWF:Ag |

| A3 | Ex29-32 | |||

| 2N | D′-D3 | Ex17-20 | Recessive | FVIII:C 5-40 IU/dL |

| Ex24-25 | VWF:Ag normal/reduced | |||

| 3 | All | 5′ VWF-Ex52 | Recessive | VWF:Ag <5 IU/dL |

| FVIII:C <10 IU/dL |

| VWD type . | VWF domain . | Mutation location . | Inheritance pattern . | Phenotype . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | All | Promoter-ex52 | Majority dominant, minority >1 mutation or recessive | VWF activity/VWF:Ag >0.7 |

| 2A/IIC | D2 | Ex11-16 | Recessive | Mostly very discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag |

| 2A/IIE | D3 | Ex22 & 25-28 | Dominant | Discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag, most <0.6 |

| 2A | A1 | Ex28 | Dominant | Discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag |

| 2A/IIA | A2 | Ex28 | Dominant | Discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag |

| 2A/IID | CK | Ex51-52 | Dominant | Discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag |

| 2B | A1 | Ex28 | Dominant | Wide range of VWF activity/VWF:Ag possible |

| 2M | A1 | Ex28 | Dominant | Discrepant VWF activity/VWF:Ag and/or VWF:CB/VWF:Ag |

| A3 | Ex29-32 | |||

| 2N | D′-D3 | Ex17-20 | Recessive | FVIII:C 5-40 IU/dL |

| Ex24-25 | VWF:Ag normal/reduced | |||

| 3 | All | 5′ VWF-Ex52 | Recessive | VWF:Ag <5 IU/dL |

| FVIII:C <10 IU/dL |

VWF mutation database: https://grenada.lumc.nl/LOVD2/VWF/variants.php.

VWD2A/IIA

Classic VWD2A/IIA mutations are located in the A2 domain (amino acids [AA] 1500-1672) and comprise half of 2A mutations listed on the VWF database.24 Mutation mechanisms include impaired VWF secretion and enhanced sensitivity to the cleaving protease, ADAMTS13, that occurs under high shear stress.25

A1 domain

Twenty percent of VWD2A mutations lie in the adjacent A1 domain (AA 1271-1458) where they impact binding to glycoprotein IB (GPIb) and include the common variants p.Arg1315Cys, p.Arg1374Cys, and p.Arg1374His. These mutations have been variously classified as resulting in VWD types 2A, 2M, and 1, as multimer abnormalities do not always appear to be detectable.26,27

D3 domain

The VWD2A/IIE phenotype was described many years ago, but mutations responsible were only described as a single VWD category in 2010.28 Mutations result in intracellular retention, relative loss of HWMW, and reduced ADAMTS13-mediated proteolysis. Missense mutations are located in ex22 and 25 to 28, many introducing/substituting cysteine residues; replacement of p.Cys1130 is the most common change.29 These mutations, like p.Arg1205His, result in rapid VWF clearance.

D2 domain

VWD2A/IIC propeptide mutations have a multimerization defect resulting in reduced HMWM. Unlike most VWD2A, mutations are recessively inherited and are located in ex11 to 16 (AA 404-768). In addition to homozygous missense mutations, patients also have small in-frame deletions/insertions with some being compound heterozygous.

CK domain

VWD2A/IID mutations are located in the cysteine knot domain and affect ex51 to 52 (AA 2730-2801). Mutations impair VWF dimerization, leading to odd numbered satellite bands on multimer analysis.30

Mutation analysis can aid understanding of disease process in VWD2A either through analysis of exon 28 alone or preferably of the entire gene.

Type 2B VWD

VWD2B results from an unusual gain-of-function mutation type.31 Dominantly inherited A1 domain missense mutations (AA 1266-1461) alter VWF confirmation, facilitating spontaneous interaction with GPIb. This can result in circulating aggregates of VWF and platelets that are cleared from the circulation, resulting in thrombocytopenia. Platelet-type VWD (PT-VWD) results from dominantly inherited gain-of-function missense mutations in GP1BA, leading to a similar phenotype.32 Treatment may differ between these 2 disorders: platelet transfusions can result in platelet clearance in VWD2B,33 where they may be helpful in PT-VWD. Genetic analysis is straightforward for these disorders, often using Sanger sequencing to examine the VWF A1 domain and GP1BA region encoding the β hairpin loop (AA 246-255).34

Type 2M VWD

Type 2M mutations reduce VWF-GPIb or VWF-collagen binding to subendothelium, with no HMWM loss. There is often a marked difference between VWF activity and VWF:Ag, with activity considerably lower than VWF:Ag. The A1 domain is the predominant mutation location (exon 28, AA 1229-1439), where missense mutations impair GPIb interaction, reducing platelet activation. Mutations affecting collagen-binding are not always sought through phenotypic analysis; they may impair binding to the more commonly used collagen types I/III or the less commonly investigated types IV/VI.35-37 These mutations are located in the A1 or A3 domains (ex28-32).24

Type 2N VWD

VWD2N missense mutations in the D′-D3 domains (ex17-25) impair binding of FVIII to VWF (VWF:FVIIIB), resulting in reduced FVIII half-life in the circulation.38 Typically, FVIII:C levels mimic those seen in mild hemophilia A (range, 5-40 IU/dL), whereas VWF:Ag levels are normal or mildly reduced.38 Inheritance is recessive; ≥1 of the 2 mutations affects VWF:FVIIIB. The second mutation can be a further copy of the same missense mutation, a different VWF:FVIIIB missense mutation, or commonly a null allele (nonsense, splice site, deletion/insertion). The most frequent mutation in the European populations is p.Arg854Gln, for which ∼1% individuals are heterozygous. Unless there is an obvious family history indicating inheritance pattern, it can be difficult to distinguish mild hemophilia A from 2N VWD. A phenotypic VWF:FVIIIB assay or genetic analysis to discriminate these 2 disorders can be used. Desmopressin response may be curtailed in 2N patients due to shortened FVIII half-life.

Type 3 VWD

In populations where consanguineous partnerships are common, the prevalence of VWD3 may be 10- to 20-fold greater than in outbred populations. In European populations, ∼1 individual/106 is affected. Patients have undetectable VWF levels (<5 IU/dL) and reduced FVIII (<10 IU/dL), resulting from lack of VWF to protect FVIII from proteolysis. Fifteen percent to 20% of mutations are missense substitutions, and these can result in a less severe phenotype, with reduced VWFpp/VWF:Ag indicating enhanced clearance from plasma, and reduced BS compared with patients having 2 null mutations. Missense mutations often result in VWF being retained within the endoplasmic reticulum as VWF is likely misfolded. Whereas VWD3 patients with null alleles in the Willebrand in the Netherlands study produced no detectable VWF, those with measurable VWFpp (indicating some VWF production) demonstrated higher VWF:Ag (0 vs 4 IU/dL), activity (0 vs 1 IU/dL), and FVIII levels (2 vs 9 IU/dL).18 The disorder is recessively inherited, with most patients having 2 null alleles. A very small proportion may develop anti-VWF antibodies, with only a rare patient where the antibody is inhibitory for 1 of the VWF activities. Genetic analysis can identify causative mutation(s) in nearly all VWD3 affected individual so that inheritance risks in relatives can be determined. Prenatal diagnosis for a possible VWD3-affected pregnancy can be undertaken using chorionic villus or amniocentesis samples from ∼11 to 18 weeks of gestation, dependent on sample type.

Clinical utility of VWF genetic testing

Molecular testing for VWD is justified in individuals in whom phenotypic assays suggest VWD, but genetic analysis may provide a more specific diagnosis to aid appropriate management. Examples are to distinguish between VWD2N and mild hemophilia A in males or symptomatic hemophilia carrier status in females; to discriminate between VWD2B and PT-VWD; to help understand the patient’s disorder where >1 mutation leads to a more complex phenotype; and to provide prenatal diagnosis for families with VWD3. For VWD1, patients where rapid VWF clearance occurs following desmopressin administration or when inheritance pattern is unclear and mutation determination can explain disease risk in relatives, genetic analysis can be useful.

Conclusion

VWF mutations are located throughout the VWF gene, resulting in a wide range of mutation types that include quantitative and qualitative disorders. VWF protein is involved in several processes that can be damaged by mutation, and the varying phenotypes in VWD illustrate the processes that are impaired.

Acknowledgments

A.C.G. receives support from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute for the Zimmerman Program (grant HL081588).

Correspondence

Anne Goodeve, Haemostasis Research Group, Department of Infection, Immunity and Cardiovascular Disease, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health, University of Sheffield, Beech Hill Rd, Sheffield S10 2RX, United Kingdom; e-mail: a.goodeve@shef.ac.uk.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.G. has received honoraria from Baxalta and Octapharma and has received funding for the von Willebrand factor mutation database from CSL-Behring.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.