Abstract

Acquired aplastic anemia (AA) is an immune-mediated bone marrow aplasia that is strongly associated with clonal hematopoiesis upon marrow recovery. More than 70% of AA patients develop somatic mutations in their hematopoietic cells. In contrast to other conditions linked to clonal hematopoiesis, such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential in the elderly, the top alterations in AA are closely related to its immune pathogenesis. Nearly 40% of AA patients carry somatic mutations in the PIGA gene manifested as clonal populations of cells with the paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria phenotype, and 17% of AA patients have loss of HLA class I alleles. It is estimated that between 20% and 35% of AA patients have somatic mutations associated with hematologic malignancies, most characteristically in the ASXL1, BCOR, and BCORL1 genes. Risk factors for evolution to MDS in AA include the duration of disease, acquisition of high-risk somatic mutations, and age at AA onset. Emerging data suggest that several HLA class I alleles not only predispose to the development of AA but may also predispose to clonal evolution in AA patients. Long-term prospective studies are needed to determine the true prognostic implications of clonal hematopoiesis in AA. This article provides a brief, but comprehensive, review of our current understanding of clonal evolution in AA and concludes with 3 cases that illustrate a practical approach for integrating results of next-generation molecular studies into the clinical care of AA patients in 2018.

Learning Objectives

Understand the relationship between the immune pathogenesis and clonal evolution in acquired aplastic anemia (AA)

Review risk factors for transformation to post-AA myelodysplastic syndrome

Develop an evidence-based approach for integrating results of AA patients’ clonal profiles into clinical care

Introduction

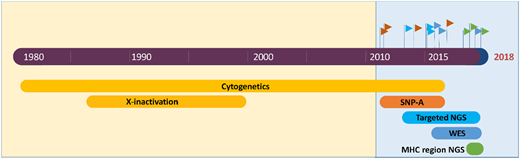

Acquired aplastic anemia (AA) is a nonneoplastic bone marrow failure that is caused by an autoimmune T lymphocyte–mediated attack on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).1 Although AA has long been noted for its association with clonal blood disorders paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), the nearly ubiquitous presence of clonal hematopoiesis in AA was appreciated only recently, made possible by advances in cytogenetic and sequencing technologies (Figure 1).2 Clonal hematopoiesis is defined by a disproportionately large fraction of hematopoietic cells arising from a single stem cell or a multipotent hematopoietic progenitor. Clonal hematopoiesis can be detected in a patient’s blood or bone marrow by identifying genetic changes (eg, mutations or chromosomal abnormalities) that have developed during an individual’s lifetime in a process called clonal evolution. This review will provide a summary of our current understanding of clonal evolution in AA and will emphasize how the most common mutations in AA reflect its immune pathogenesis. Current data on the risk factors for MDS transformation in AA will be reviewed. The article will conclude with 3 cases to illustrate an evidence-based practical approach for integrating results of next-generation molecular studies into the clinical management of AA in 2018.

Next-generation sequencing and cytogenetics studies of clonal hematopoiesis in acquired AA. Advances in next-generation genome analysis technology, including single nucleotide polymorphism arrays (SNP-A), targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and NGS-based HLA typing, have generated several waves of studies of clonal evolution in AA, uncovering the near-ubiquitous presence of clonal hematopoiesis in the recovering marrow of AA patients.

Next-generation sequencing and cytogenetics studies of clonal hematopoiesis in acquired AA. Advances in next-generation genome analysis technology, including single nucleotide polymorphism arrays (SNP-A), targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and NGS-based HLA typing, have generated several waves of studies of clonal evolution in AA, uncovering the near-ubiquitous presence of clonal hematopoiesis in the recovering marrow of AA patients.

Clonal hematopoiesis in AA

Clonal hematopoiesis is present in >70% of AA patients

Recent advances in genome analysis, including single nucleotide polymorphism arrays (SNP-As), targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and NGS-based HLA typing, have exposed somatic mutations in AA patients, catapulting AA to the forefront of conditions linked to clonal hematopoiesis (Figures 1, 2). Comprehensive genome analysis can identify clonal hematopoiesis in hematopoietic cells of 71% to 85% of AA patients,3-5 making AA (together with PNH6,7 ) the nonneoplastic blood disease most singularly linked to clonal hematopoiesis. The frequency of somatic mutations in AA increases with age; however, even in pediatric-onset AA, somatic mutations are present in >60% of patients.4,5 Clonal hematopoiesis develops at a striking prevalence of 80% to 100% in adults with AA.3,4 A smaller, but significant fraction, of patients acquire mutations previously associated with hematologic malignancies: across studies of AA patients, MDS-associated mutations are detected at a median prevalence of 21%, ranging from as low as 5% to as high as 54%3-5,7-12 (Figure 2). The variability across studies reflects differences in patient cohort characteristics with varying age, the inclusion of patients who progressed to secondary MDS, different testing methodologies, and differences in the number of genes sequenced.

A tabulated summary of major NGS studies of clonal hematopoiesis in acquired AA. Shown is a tabulated summary of major NGS studies in AA performed over the last 5 years, with annotated baseline study parameters (patients’ age, cohort size, the inclusion of patients with post-AA secondary MDS and cytogenetic abnormalities, analysis methodology, and the number of genes targeted by NGS). The overall prevalence of clonal hematopoiesis by all modalities, including WES and the rate of MDS-associated somatic mutations, are shown in the right 2 columns. Data are visually highlighted using in-table bar plots. N/A, not available; NE, not evaluable.

A tabulated summary of major NGS studies of clonal hematopoiesis in acquired AA. Shown is a tabulated summary of major NGS studies in AA performed over the last 5 years, with annotated baseline study parameters (patients’ age, cohort size, the inclusion of patients with post-AA secondary MDS and cytogenetic abnormalities, analysis methodology, and the number of genes targeted by NGS). The overall prevalence of clonal hematopoiesis by all modalities, including WES and the rate of MDS-associated somatic mutations, are shown in the right 2 columns. Data are visually highlighted using in-table bar plots. N/A, not available; NE, not evaluable.

The most common somatic alterations in AA derive from the immune pathogenesis of AA

Somatic mutations in AA overlap only partially with mutations that characterize clonal hematopoiesis in related conditions, such as age-associated clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), MDS, inherited bone marrow failure syndromes, and even classical PNH. The top somatic changes in AA, loss of PIGA (which causes clonal populations of cells with the PNH phenotype) and loss of HLA alleles, are pathognomonic for immune-mediated marrow failure. Approximately 40% of AA patients have flow cytometric evidence of PNH cells.13 Although the exact mechanism by which PNH cells clonally expand is not known, the available evidence points to their relative protection from T-cell–mediated autoimmunity.14,15

The second most common somatic change in AA is the loss of selected HLA class I alleles.5,16-19 HLA loss in AA can occur by 2 genetic mechanisms. The more common mechanism is the mitotic recombination at the major histocompatibility complex region of the chromosome arm 6p, which serves to eliminate the haplotype carrying the pathogenic HLA allele in the HSPCs. Detected by SNP-A genotyping as copy number–neutral loss-of-heterozygosity (CN-LOH), 6p CN-LOH occurs in ∼11% of AA patients.3,18-20 The second mechanism of HLA loss is through loss-of-function mutations in pathogenic HLA class I risk alleles. This mechanism was uncovered only recently, made possible by the advent of NGS optimized for the highly repetitive major histocompatibility complex region and the HLA genes.5,16,17,21 Targeted HLA NGS in combination with SNP-A can detect somatic HLA loss in 17% of AA patients.5 HLA alleles that are lost in HSPCs in AA are not random; instead, mutations and 6p CN-LOH recurrently target a small number of AA predisposition alleles. The most commonly inactivated alleles are HLA-B*14:02 and HLA-B*40:02, which are the HLA class I alleles most significantly overrepresented in AA compared with population-based controls of the same ethnicity.5,16,18,19 Hematopoietic clones with somatic loss of HLA can expand in the absence of other mutations, indicating that HLA loss by itself is sufficient to confer a growth advantage to HSPCs in AA, likely by avoiding recognition by the autoreactive T cells.5,16,21

Loss of PIGA and HLA alleles is the signature change of immune-mediated marrow failure, and it occurs only rarely in healthy aged individuals or patients with MDS.2 Although all patients with classical hemolytic PNH, a related marrow failure syndrome, by definition have PIGA mutations and a large PNH clone, they have not been found to have somatic HLA loss, suggesting the lack of additive advantage for HLA loss in PNH cells.5

On the origin of clones by means of natural selection (or the preservation of favored clones in the struggle for life)

Aside from recurrent mutations in PIGA and HLA, the most striking characteristic of AA hematopoiesis is the sheer diversity of somatic mutations.2-4,10 When recovering hematopoietic cells of AA patients are analyzed by WES, the majority of somatic mutations in children and young adults are private and nonrecurrent; older adults also have private mutations, but they additionally exhibit an age-dependent increase in recurrent driver mutations associated with CHIP.3,5,7,17,22

Perhaps the most apt parallel to understanding clonal hematopoiesis in AA is Darwinian evolution, whereby individual hematopoietic cells “struggle for existence” in the harsh autoimmune environment of AA. Individual HSPCs in healthy individuals stochastically acquire a variety of private background mutations over time, carrying ∼0 to 1 somatic mutations per HSPC exome in cord blood, 1 to 3 somatic mutations per HSPC exome in individuals at the age of 20s to 30s, and ≥4 somatic mutations per HSPC exome at 40 years, respectively; each HSPC normally contributes <0.1% of cells in peripheral blood.23 With aging, there is a stereotypical outgrowth of cells bearing mutations in epigenetic regulators of stem cell renewal DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1, as well as others, together known as CHIP.24 This age-dependent background of stochastic mutations also shapes clonal diversity in AA, as HSPCs with a variety of background mutations “struggle for existence” and may derive a selective advantage from their somatic differences. Indeed, close evaluation of private somatic mutations in AA patients suggests that some are likely functional.17 The depleted stem cell pool further magnifies the clonal contribution of such private mutations.

Among the total diversity of somatic mutations in AA, it is instructive to note mutations that are overrepresented in AA compared with their expected frequency in the age-matched population, because these are more likely to have been selected more specifically by the AA bone marrow milieu. Interestingly, aside from PIGA and HLA, AA patients have a disproportionate number of mutations in epigenetic regulators ASXL1, BCOR, and BCORL1,3,5,7 suggesting that these genetic changes likely confer a selective advantage specific to the AA autoimmune environment. Other clonal changes associated with AA include cytogenetic abnormalities, characteristically monosomy 7/del(7q), trisomy 8, and del(13q).2

Secondary MDS evolving from AA

Several retrospectives analyses evaluated clonal evolution in AA patients who developed secondary MDS. Altogether, >80 cases of post-AA secondary MDS have now been analyzed by NGS3,7,9,12,25 (Table 1), leading to the identification of several risk factors for post-AA MDS. The most strongly supported risk factors are the duration of disease from the time of diagnosis of AA and the acquisition of prognostically adverse somatic mutations. Emerging risk factors include the age at AA onset, short leukocyte telomere lengths, HLA class I risk alleles, and, more controversially, the possible role of therapeutic agents.

Studies of clonal evolution in patients who progressed to post-AA secondary MDS

| Reference (year) . | Study design (methodology) . | Median age, (range), y . | Patients, n . | Pre-MDS analysis . | MDS analysis . | Associations reported . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with malignancy-associated mutations, n (%) . | Reported mutations (n) . | Median allelic fraction (%) . | Patients with malignancy-associated mutations, n (%) . | Reported mutations (n) . | Karyotype at MDS transformation (n, %) . | |||||

| 9 (2014)* | Retrospective (Targeted NGS) | 54 (17-83) | 17 | 11 (65) | None (6), ASXL1 (7), DNMT3A (3), BCOR (1), ERBB2 (1), TET2 (1), U2AF1 (1) | 31 | N/A | N/A | Normal (10, 58), monosomy 7 (4, 24%), others in 1 patient each | AA patients with somatic mutations had a higher rate of MDS evolution. Patients with somatic mutations had shorter leukocyte telomere lengths. |

| 12 (2015)* | Retrospective (Sanger sequencing of ASXL1, TET2, RUNX1, TP53, K-RAS, N-RAS) | 21 (7-76) | 9 | 4 (44) | ASXL1 (3), TET2 (1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Normal (5, 56), monosomy 7 (2, 22), others in 1 patient each | Patients with mutations in ASXL1 had a higher rate of MDS evolution. |

| 25 (2015) | Retrospective (WES, targeted NGS) of AA patients with monosomy 7 | 27 (18-68) | 13 | 2 (15) | Patient 1 (ASXL1, DNMT3A, SETBP1, DOT1L, STAT3). Patient 2 (DNMT3A, RUNX1). | ∼30 | 4 (31) | ASXL1 (4), DNMT3A (3), RUNX1 (3), SETBP1 (2), others | Monosomy 7 (13, 100) | Relatively low frequency of somatic mutations in patients with monosomy 7. Patients with monosomy 7 had shorter leukocyte telomere lengths. |

| 3 (2015)* | Retrospective (WES, targeted NGS) | 40.5 (2.5-88) | 16 | N/A | Various | N/A; clone size expanded over time | N/A | N/A | N/A | Patients with mutations in ASXL1, DNMT3A, RUNX1, JAK2, and JAK3 had worse overall and progression-free survival. Patients with mutations in PIGA, BCOR, BCORL1 had better overall and progression-free survival. |

| 7 (2017) | Retrospective (WES, targeted NGS) | 62 (18-75) | 23 | 4 of 8 (50) | RUNX1 (2), ASXL1 (1), U2AF1 (1), JAK2 (1), PHF6 (1), SETBP1 (1), TET2 (1) | 26 | 15 (65) | ASXL1, RUNX1, splicing factors, SETBP1, others | Monosomy 7 (17, 63) | Mutations in ASXL1, RUNX1, splicing factors, and CBL were associated with post-AA secondary MDS. |

| Reference (year) . | Study design (methodology) . | Median age, (range), y . | Patients, n . | Pre-MDS analysis . | MDS analysis . | Associations reported . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with malignancy-associated mutations, n (%) . | Reported mutations (n) . | Median allelic fraction (%) . | Patients with malignancy-associated mutations, n (%) . | Reported mutations (n) . | Karyotype at MDS transformation (n, %) . | |||||

| 9 (2014)* | Retrospective (Targeted NGS) | 54 (17-83) | 17 | 11 (65) | None (6), ASXL1 (7), DNMT3A (3), BCOR (1), ERBB2 (1), TET2 (1), U2AF1 (1) | 31 | N/A | N/A | Normal (10, 58), monosomy 7 (4, 24%), others in 1 patient each | AA patients with somatic mutations had a higher rate of MDS evolution. Patients with somatic mutations had shorter leukocyte telomere lengths. |

| 12 (2015)* | Retrospective (Sanger sequencing of ASXL1, TET2, RUNX1, TP53, K-RAS, N-RAS) | 21 (7-76) | 9 | 4 (44) | ASXL1 (3), TET2 (1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Normal (5, 56), monosomy 7 (2, 22), others in 1 patient each | Patients with mutations in ASXL1 had a higher rate of MDS evolution. |

| 25 (2015) | Retrospective (WES, targeted NGS) of AA patients with monosomy 7 | 27 (18-68) | 13 | 2 (15) | Patient 1 (ASXL1, DNMT3A, SETBP1, DOT1L, STAT3). Patient 2 (DNMT3A, RUNX1). | ∼30 | 4 (31) | ASXL1 (4), DNMT3A (3), RUNX1 (3), SETBP1 (2), others | Monosomy 7 (13, 100) | Relatively low frequency of somatic mutations in patients with monosomy 7. Patients with monosomy 7 had shorter leukocyte telomere lengths. |

| 3 (2015)* | Retrospective (WES, targeted NGS) | 40.5 (2.5-88) | 16 | N/A | Various | N/A; clone size expanded over time | N/A | N/A | N/A | Patients with mutations in ASXL1, DNMT3A, RUNX1, JAK2, and JAK3 had worse overall and progression-free survival. Patients with mutations in PIGA, BCOR, BCORL1 had better overall and progression-free survival. |

| 7 (2017) | Retrospective (WES, targeted NGS) | 62 (18-75) | 23 | 4 of 8 (50) | RUNX1 (2), ASXL1 (1), U2AF1 (1), JAK2 (1), PHF6 (1), SETBP1 (1), TET2 (1) | 26 | 15 (65) | ASXL1, RUNX1, splicing factors, SETBP1, others | Monosomy 7 (17, 63) | Mutations in ASXL1, RUNX1, splicing factors, and CBL were associated with post-AA secondary MDS. |

N/A, not available.

Data shown correspond to the subset of patients who progressed to post-AA secondary MDS.

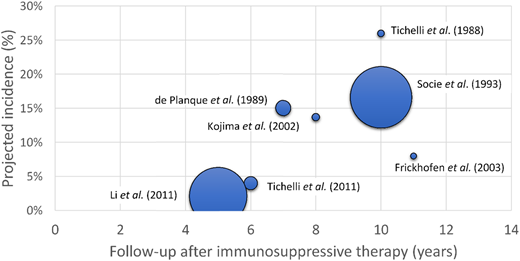

The risk of transformation to secondary MDS in AA increases with disease duration

Prospective studies of late complications in AA identified an increased incidence of transformation to secondary MDS/acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in AA patients over time.26-34 The incidence of secondary MDS/AML at 5 to 6 years after immunosuppressive therapy is estimated at 2% to 4%, going up to 15% to 26% at 10 years of follow-up26-34 (Figure 3, Table 2).

The incidence of post-AA secondary MDS as a function of disease duration. A scatter plot of projected incidence of secondary MDS/AML observed in long-term follow-up of prospective studies of AA patients. The size of each data point is proportional to the number of patients included in each study.

The incidence of post-AA secondary MDS as a function of disease duration. A scatter plot of projected incidence of secondary MDS/AML observed in long-term follow-up of prospective studies of AA patients. The size of each data point is proportional to the number of patients included in each study.

Incidence of late clonal complications in patients with acquired AA treated with immunosuppression

| Reference (year) . | Study design . | Patients, n . | Age, median (range), y . | Follow-up, median, y . | Patients with PNH, n . | Projected incidence of PNH, % (follow-up, y) . | Patients with secondary MDS/AML, n . | Projected incidence of MDS/AML, % (follow-up, y) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 (1989) | Retrospective: EBMT registry analysis of late survivors post-IST (survived > 2 y) | 223 | 23 (1-73) | 4 | 19 | 13 (7) | 12 | 15 (7) |

| 28 (2011) | Prospective: IST, with or without G-CSF | 192 | 46 (2-81) | 6 | 37 | 19 (6) | 6 | 4 (6) |

| 27 (1988) | Prospective: ALG + androgen | 103 | 20 (8-52)* | 3 | 13 | ∼31 (10) | 9 | 26 (10) |

| 29 (2003) | Prospective: ATG + CsA | 122 | 35 (N/A) | 7 | 7 | 10 (7) | N/A | N/A |

| 30 (2011) | Retrospective: varied, including G-CSF, CsA, ATG, androgens | 802 | 23 (3-71) | 6 | 21 | 1.7 (5) | 19 | 2.1 (5) |

| 31 (2002) | Prospective: ALG + CsA + danazol, with or without G-CSF | 113 | 9 (1-18) | 8 | N/A | N/A | 12 | 13.7 (8) |

| 32 (2003) | Prospective: ATG, with or without CsA | 94 | 32 (2-80) | 11 | 5 | 10 (11) | 4 | 8 (11) |

| 33 (1993) | Retrospective: EBMT registry analysis, various IST regimens | 860 | 29 (3-83)† | 3 | N/A | N/A | 43 | 16.6 (10) |

| 34 (2017) | Prospective: ATG + CsA + eltrombopag | 92 | 32 (3-82) | 2 | 2 | N/A | 5 | N/A, <8 (2) |

| Reference (year) . | Study design . | Patients, n . | Age, median (range), y . | Follow-up, median, y . | Patients with PNH, n . | Projected incidence of PNH, % (follow-up, y) . | Patients with secondary MDS/AML, n . | Projected incidence of MDS/AML, % (follow-up, y) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 (1989) | Retrospective: EBMT registry analysis of late survivors post-IST (survived > 2 y) | 223 | 23 (1-73) | 4 | 19 | 13 (7) | 12 | 15 (7) |

| 28 (2011) | Prospective: IST, with or without G-CSF | 192 | 46 (2-81) | 6 | 37 | 19 (6) | 6 | 4 (6) |

| 27 (1988) | Prospective: ALG + androgen | 103 | 20 (8-52)* | 3 | 13 | ∼31 (10) | 9 | 26 (10) |

| 29 (2003) | Prospective: ATG + CsA | 122 | 35 (N/A) | 7 | 7 | 10 (7) | N/A | N/A |

| 30 (2011) | Retrospective: varied, including G-CSF, CsA, ATG, androgens | 802 | 23 (3-71) | 6 | 21 | 1.7 (5) | 19 | 2.1 (5) |

| 31 (2002) | Prospective: ALG + CsA + danazol, with or without G-CSF | 113 | 9 (1-18) | 8 | N/A | N/A | 12 | 13.7 (8) |

| 32 (2003) | Prospective: ATG, with or without CsA | 94 | 32 (2-80) | 11 | 5 | 10 (11) | 4 | 8 (11) |

| 33 (1993) | Retrospective: EBMT registry analysis, various IST regimens | 860 | 29 (3-83)† | 3 | N/A | N/A | 43 | 16.6 (10) |

| 34 (2017) | Prospective: ATG + CsA + eltrombopag | 92 | 32 (3-82) | 2 | 2 | N/A | 5 | N/A, <8 (2) |

ALG, antilymphocyte globulin; ATG, anti-thymocyte globulin; CsA, cyclosporine A; EBMT, European Cooperative Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; IST, immunosuppressive therapy; N/A, not available.

Mean age.

Age corresponds to patients with MDS/AML evolution.

The role of somatic mutations and cytogenetic changes in evolution to secondary MDS

In a retrospective analysis of AA patients who evolved to MDS, 65% of patients were found to have somatic mutations in MDS-associated genes.7 Another one third of AA patients developed secondary MDS without MDS-associated somatic mutations; the vast majority of these patients had a total or a partial loss of chromosome 7.7,25

Compared with the overall rate of MDS-associated somatic mutations in AA, AA patients who evolve to MDS have a higher frequency of MDS-associated somatic mutations during the AA phase (estimated at 44% to 65% compared with 20% to 25% in AA patients overall) (Figure 2, Table 1). Although retrospective studies can be affected by referral and ascertainment patterns, several groups identified high-risk somatic mutations associated with MDS after an AA diagnosis, particularly mutations in ASXL1, RUNX1, and splicing factor genes when present at a high allelic fraction.3,7,9,12 In contrast, the most common mutations associated with aging (mutations in the DNMT3A and TET2 genes) were not found to influence the risk for MDS progression significantly.7,12 Similarly, the most common alterations in AA (somatic loss of PIGA and HLA alleles), as well as mutations in BCOR and BCORL1, were not linked to secondary MDS. These latter mutations were found to occur in small or only moderately sized clones that were typically stable over time (eg, for BCOR/BCORL1) or were associated with the polyclonal expansion of several independent clones (eg, for PIGA and HLA).3,5,16,21 In a study of 439 AA patients, patients who carried mutations in PIGA, BCOR, and BCORL1 genes had an improved overall and progression-free survival.3

There is a strong interaction between the presence of mutations and disease duration. Although transformation to MDS in AA is a late complication, somatic mutations typically develop within 6 months of immunosuppressive therapy; for many patients, mutations can already be identified in diagnostic bone marrow specimens, albeit at a very low allelic burden.3 Patients whose mutations were detected at the time of diagnosis had the shortest time to disease evolution.7 At ∼7 to 8 years of follow-up, as many as 40% of patients with adverse prognostic mutations had developed MDS, a rate higher than the ∼15% to 25% historical rate of MDS evolution after 10 years and higher than the ∼5% rate of MDS transformation in patients with mutations in PIGA, BCOR, and BCORL13,9 (Figure 3, Table 2).

Because available studies of post-AA MDS have been mostly retrospective and limited in the number of patients analyzed, it is helpful to consider post-AA MDS within the broader context of premalignant clonal hematopoiesis. The role of somatic mutations in the subsequent development of AML was recently evaluated in 2 large prospective observational cohorts: the Women’s Health Initiative and the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition.35,36 Somatic mutations found in the blood of 188 women from the Women’s Health Initiative cohort and 95 individuals from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort who later developed AML were compared with mutations in the 181 and 414 age- and gender-matched controls from these respective cohorts. Both studies found that individuals who had somatic mutations on their initial assessment were more likely to develop AML many years later compared with individuals without mutations.35,36 Mutations in several specific genes, such as TP53, splicing factors, and IDH1/IDH2, were associated with an increased risk for AML.35,36 Compared with the estimated 2.7/100 000 per year incidence of AML in patients without high-risk mutations, the incidence of AML in patients who had high-risk mutations was significantly increased (eg, estimated at ∼14/100 000 per year in patients with mutations in the TP53 gene).36 Despite a large number of individuals analyzed, the number of patients carrying each specific mutation was only modest, limiting the ability to determine the prognostic impact of the less frequent mutations. In agreement with these population-based studies, AA patients carrying high-risk mutations, such as mutations in RUNX1 and splicing factor genes, were also found to have an increased rate of malignant transformation.3,7,9,12 One notable difference between AA and clonal hematopoiesis more generally was the apparent adverse effect of mutations in ASXL1 in AA,3,7,9,12 whereas a similar adverse effect was not seen in the general population.36,37 Future studies will likely uncover additional factors that modify the risk for MDS in AA, such as the potential effects of response to immunosuppression, quality of remission, immunogenetic and ethnic differences, and of therapeutic agents.

Among the cytogenetic abnormalities in post-AA MDS, the most characteristic change is monosomy 7/del(7q), identified in 20% to 60% of AA patients who evolve to MDS. Unlike monosomy 7 in primary MDS, in which it is commonly associated with TP53 mutations and a complex karyotype, monosomy 7 in post-AA secondary MDS frequently presents as an isolated cytogenetic abnormality or in combination with somatic mutations, most commonly in the RUNX1 and ASXL1 genes.3,7,9,12

The role of age of AA onset in clonal evolution

One of the strongest predictors of clonal hematopoiesis with MDS-associated somatic mutations is the patient’s age at AA diagnosis. When all markers of clonality are evaluated, patients with childhood-onset AA have only moderately lower rates of clonal hematopoiesis (∼60%) compared with 80% in adults.3,5,17 However, the rates of driver mutations, previously associated with MDS and hematologic malignancies, are dramatically lower in pediatric patients. In a multi-institutional study of clonal hematopoiesis in AA, 22% of the 82 patients under the age of 20 years were found to have MDS-associated mutations, a rate significantly lower than the 39% of the 357 adult patients who were analyzed using the same highly sensitive NGS technique.3,22,37 Similar results were seen in a smaller North American cohort analyzed by WES, in which the rate of MDS-associated mutations in pediatric-onset AA was also significantly lower.5 In contrast to adult-onset AA, clonal hematopoiesis in pediatric patients primarily consisted of somatic mutations in HLA, PIGA, and private mutations.5 The age-dependent increase in MDS-associated changes is consistent with the previously described stochastic accumulation of mutations in HSPCs at an estimated rate of ∼0.13 exonic mutations per year23 and clonal expansion of MDS-associated driver mutations with age.38-40

HLA class I risk alleles and clonal evolution

Emerging data on the role of HLA class I–mediated autoimmunity in AA suggest that patients who carry HLA class I risk alleles may have a higher risk for MDS-associated clonal hematopoiesis.5 AA risk alleles HLA-B*14:02 and HLA-B*40:02 have a significantly higher prevalence in AA patients compared with population-based controls, and their somatic loss provides a growth advantage to the HSPCs in AA patients.5,16-19,41 AA patients who carry HLA class I risk alleles appear to have more MDS-associated driver mutations and chromosomal rearrangements than patients without HLA risk alleles, particularly in adults.5 It is interesting to speculate that as we learn more about the role of immunogenetic variation in AA, we may uncover population-based differences in long-term AA outcomes based on immunogenetic variation, similar to the known ethnic differences in the incidence of AA.

An association of clonal changes with telomere attrition

Multiple studies evaluated telomere attrition in patients with clonal evolution in AA.9,11,25,42 Treatment-naive patients with leukocyte telomeres in the bottom quartile were found to have a more severe disease course, with more frequent cytogenetic evolution and worse survival.42 To a large degree, total leukocyte telomere lengths in treatment-naive AA patients reflect the telomere lengths in the lymphocyte compartment, where shorter telomere lengths were found to correlate with T lymphocyte activation and entry into the S phase of the cell cycle.43 Thus, leukocyte telomere lengths measured at AA diagnosis may be a marker of increased lymphocyte activation and greater severity of autoimmune disease. Indeed, shorter lymphocyte telomere lengths were found to be predictive of poorer response to immunosuppressive therapy44,45 and to correlate with relapse.42

When analyzing total leukocyte telomere lengths of AA patients later in disease, patients with monosomy 7 or somatic mutations were also noted to have shorter telomeres9,11,25 and a higher rate of telomere attrition preceding the development of cytogenetic changes.25 Shorter telomere lengths later in disease may reflect greater hematopoietic cell proliferative history and higher replicative stress. Additionally, once telomeres have reached a critical length, telomere attrition itself may contribute to chromosomal instability.

A potential association with therapeutic agents

Several retrospective analyses of AA patients’ outcomes identified an association between the use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and evolution to monosomy 7 MDS.30,31,46-48 Importantly, subsequent randomized prospective studies comparing immunosuppression with and without G-CSF failed to confirm this association.28,49,50 Based on these data, the previously identified link between clonal evolution and G-CSF is now believed to reflect confounding by indication, whereby patients with more severe AA are also more likely to have received G-CSF.51,52

Similar to G-CSF use, concerns regarding the potential stimulation of abnormal cytogenetic clones have arisen in studies using thrombopoietin receptor agonist eltrombopag to treat patients with refractory AA. Among 43 patients with refractory AA treated with eltrombopag, 8 patients (18.6%) developed new cytogenetic abnormalities within 3 to 13 months of eltrombopag therapy, with 5 of the 8 patients developing monosomy 7.53,54 When used in frontline therapy, cytogenetic abnormalities developed in 7 of 92 patients (actuarial incidence of 8% at 2 years), with 5 of the 7 patients developing monosomy 7.34 Prospective, randomized studies will be essential to determine the effects of eltrombopag on clonal evolution in AA. Notably, because of the concerns for the potential adverse effect of eltrombopag on cytogenetic evolution in refractory AA, studies using eltrombopag in combination with standard immunosuppression upfront have so far excluded patients with MDS-defining clonal cytogenetic abnormalities.34,55

How I incorporate findings of clonal hematopoiesis into the clinical care of patients with AA in 2018

Using clonal markers of immune evasion as an adjunctive diagnostic test in AA

Case study 1.

A previously healthy 63-year-old female presents for evaluation of chronic pancytopenia. Over the last year, she developed progressive fatigue and easy bruising. A complete blood count today reveals a white blood cell count of 3.5 × 103 cells/µL with 40% neutrophils, a hemoglobin of 9.9 g/dL with a mean corpuscular volume of 102 fL, and an absolute reticulocyte count of 28 × 103 cells/µL. The platelet count is 27 × 103 cells/µL. An extensive evaluation of possible toxic exposures, nutritional deficiencies, occult rheumatologic disorders, and viral infections is unrevealing. A bone marrow biopsy shows a variably cellular marrow ranging from <5% to 40% and averaging ∼20% overall. There is an erythroid predominance with no significant morphologic dysplasia. Cytogenetic studies confirm a normal female karyotype. An NGS panel targeting mutations linked to MDS is negative. Flow cytometry for PNH reveals a minute glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor–deficient granulocyte clone of 0.01%. SNP-A of peripheral blood shows an ∼10% clone with 6p CN-LOH.

An evaluation of a patient with pancytopenia and a hypocellular marrow requires a broad differential diagnosis with systematic exclusion of diverse etiologies. Although progress toward the development of diagnostic tests and biomarkers for AA is being made,56,57 in 2018 the diagnosis of AA continues to be that of exclusion. Thus, in patients with a bland evaluation, especially if they are refractory to immunosuppressive therapy, there is an inherent element of diagnostic uncertainty. In the case description above, the primary diagnostic considerations given the patient’s age, cytopenias, and marrow hypocellularity are nonsevere or evolving AA vs hypocellular MDS. In this setting, identification of clonal markers suggestive of immune-mediated bone marrow failure (eg, PNH and 6p CN-LOH) can be helpful in confirming the immune pathogenesis of her marrow dysfunction. Identifying a somatic mutation linked to immune-mediated marrow failure can be particularly useful in younger patients, in whom inherited bone marrow failure can sometimes present as isolated AA. In that situation, finding a PNH or an acquired 6p CN-LOH clone can effectively steer the diagnosis away from inherited disorders.58 In contrast to AA, in which PNH clones are present in up to 40% of patients, PNH is exceedingly rare in inherited bone marrow failure, with only 2 reports of PNH in presumed cases of Fanconi anemia.58,59 Similarly, 6p CN-LOH occurs in ∼11% to 12% of AA patients but is very rare in inherited bone marrow failure, normal aging, and MDS.2,20 It is important to note that when PNH screening is used to detect subclinical PNH clones, it should be performed using multiparameter PNH flow cytometry by a laboratory experienced in PNH detection, because false-positive PNH clones have been noted in blinded PNH screening by ∼16% of laboratories.57

Avoiding growth factors in AA patients with MDS-associated cytogenetic abnormalities, pending long-term safety data

Case study 2

A 74-year-old woman presents for follow-up of AA. She was initially diagnosed with severe AA 6 months ago, after presenting with pancytopenia with a markedly hypocellular marrow without overt myelodysplasia. Metaphase cytogenetics showed a deletion of 13q in 11 of 20 metaphases. There were no MDS-associated mutations identified by targeted NGS. The patient was treated with standard immunosuppressive therapy with horse anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) and cyclosporine A and achieved a partial response, with an absolute neutrophil count of 1080 × 103 cells/µL and a platelet count of 24 × 103 cells/µL. However, she continues to require red cell transfusions. A bone marrow biopsy performed 6 months after immunosuppressive therapy shows a variably cellular marrow, ranging from <5% to 50% cellularity, without overt morphologic dysplasia. Cytogenetics shows persistent deletion of 13q. Targeted NGS panel reveals a new variant of unknown significance in the PTPN11 gene at 30% allele frequency. Because eltrombopag is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for patients with AA who have had insufficient response to immunosuppression, you contemplate adding eltrombopag to her current regimen of cyclosporine.

Introduction of eltrombopag into the clinical care of AA patients is one of the most significant breakthroughs in the care of AA within the last decade. Nearly 40% of patients with refractory AA achieve a hematologic response to eltrombopag, and some patients can achieve a long-lasting trilineage response.53,54 In addition to stimulating thrombopoiesis, eltrombopag is thought to directly stimulate proliferation of HSPCs, probably by counteracting inhibitory effects by interferon-γ on thrombopoietin receptor signaling.60 Because of its action on HSPCs and the concerns for cytogenetic evolution in patients with refractory AA treated with eltrombopag,53 subsequent studies have excluded patients with MDS-defining abnormalities. The most common cytogenetic abnormality observed in patients treated with eltrombopag was the development of monosomy 7. Thus, patients who have clonal aberrations of chromosome 7, including transient monosomy 7, should not be managed with eltrombopag pending further safety data. With regard to other cytogenetic abnormalities, there are insufficient data to speculate on the effect of eltrombopag on long-term clonal evolution. In the case presented above, the patient has a deletion of chromosome 13q, which, in patients with AA, has been associated with a relatively benign clinical course.61 However, given inadequate experience and lack of safety data on eltrombopag use in AA patients with cytogenetic abnormalities, the most conservative approach in 2018 is to avoid eltrombopag in this population pending additional safety information. In AA patients receiving eltrombopag therapy, I also perform routine bone marrow surveillance for cytogenetic evolution and morphologic dysplasia bi-annually.

Using molecular data to guide surveillance

Case study 3

A 56-year-old female with a history of AA presents for routine follow-up. Three years ago, she was diagnosed with very severe AA when she presented with pancytopenia and aplastic bone marrow and was found to have a PNH clone of 9% in her granulocytes. She was treated with horse ATG and cyclosporine A, achieving a complete remission with normalization of blood counts after 6 months of therapy. A bone marrow biopsy performed 1 year after immunosuppression revealed normally maturing trilineage hematopoiesis with a normal karyotype. She completed cyclosporine A taper last year, and currently feels well and has a normal peripheral blood count. Her granulocyte PNH clone has decreased to <1%. Targeted NGS panel of MDS-associated mutations has been performed and revealed 2 MDS-associated pathogenic mutations, in ASXL1 and PHF6, at 33% and 9% allele frequency, respectively.

NGS of hematopoietic cells in patients with AA have shown that 20% to 25% of all studied patients and ∼40% of adults with AA develop MDS-associated somatic mutations over time.3 How specific mutations affect patient outcomes is not well understood and will require long-term prospective studies of a large number of AA patients to determine the mutations’ prognostic significance. However, based on the currently published studies, certain somatic mutations, such as those in the ASXL1, RUNX1, splicing factor genes, SETBP1, and CBL genes, have been associated with a higher rate of transformation to secondary MDS, possibly as high as ∼40% after ∼7-8 years of follow-up based on retrospective data.3,9 In contrast, mutations in TET2 and DNMT3A do not appear to increase the rate of MDS transformation significantly,7,12 and patients with mutations in PIGA, BCOR, and BCORL1 evolve to MDS less frequently.3,9 In addition to somatic mutations, other intangible factors may influence an individual patient’s risk for MDS evolution, including response to immunosuppressive therapy, quality of remission, immunogenetic or ethnic differences, and effects of medications and other exposures. In my clinical practice, I conservatively counsel patients with adverse prognostic mutations, such as the patient in the case above, regarding a moderately increased risk for late transformation to MDS and recommend periodic surveillance with a complete blood count and differential every 3 to 6 months. For younger patients and those with new or progressive cytopenias, I also proactively explore allogeneic transplant donor possibilities in the case that the patient develops late MDS progression and have a low threshold for bone marrow surveillance with full cytogenetic and molecular studies with any changes in hematologic parameters.

Conclusions

The last decade has rapidly expanded our understanding of clonal evolution in AA and its relationship to the immune pathogenesis of AA. More remains to be learned regarding prognostic implications of specific mutations. Conservative interpretation of clonal profiles can be informative in selected cases, particularly in providing ancillary support for the diagnosis of immune-mediated marrow failure and in helping to guide longitudinal surveillance of late clonal complications.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks her mentor, Dr. Monica Bessler, who initiated the studies of clonal hematopoiesis in AA at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), established the Penn/CHOP Bone Marrow Failure registry and patient sample repository, and served as the first director of the Penn/CHOP Comprehensive Bone Marrow Failure Center. The author thanks Dr. Timothy Olson for helpful discussions and the anonymous reviewers for insightful comments on this manuscript. The author is grateful to the patients and their families for participating in research studies of bone marrow failure.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (K08 HL132101) and by the Aplastic Anemia and MDS International Foundation.

Correspondence

Daria V. Babushok, PCAM 12 South, 3400 Civic Center Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: daria.babushok@uphs.upenn.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.