Abstract

Marginal zone lymphomas are indolent diseases. Overall survival rates are very good, but patients tend to relapse and may do so several times. The concept of treatment sequencing is therefore important and necessary to preserve adequate organ function and to avoid excessive toxicity, with the final goal of achieving long survival times. Systemic treatments and chemotherapy are considered to be an option in multiply relapsing disease, in cases that are in an advanced stage at presentation or relapse, and in cases where initial local treatments lack efficacy. Targeted agents and new drugs can provide chemotherapy-free alternatives in heavily pretreated patients.

Learning Objectives

Apply the most correct frontline treatment in extranodal, nodal or splenic marginal zone lymphoma

Manage disease relapse in the era of targeted agents and new drugs

Introduction

Marginal zone lymphomas (MZLs) are rare diseases with a heterogeneous clinical presentation: extranodal MZL (EMZL) of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) is the most common, accounting for nearly 70% of all MZLs, with the possible involvement of any anatomic site. They are followed by splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL), which represents roughly 20% of cases, and by nodal MZL (NMZL), the most infrequently occurring entity.1,2

Given their rarity, it is often difficult to conduct clinical trials specifically designed for patients with MZL. Existing trials of patients with MZL generally include diseases with different presentations (eg, MZL collectively or multiple-site EMZL), although there are some trials for gastric MZL, as it is the extranodal site most frequently involved in MALT lymphoma. Most data on treatment of these entities are extrapolated from umbrella trials involving patients with indolent B-cell lymphomas or from retrospective reviews. In most cases, current guidelines are based on expert recommendations rather than evidence-based statements, as there are few randomized trials.3,4

MZLs are indolent diseases, and patients generally have long survival times but show a tendency to relapse, perhaps several times, as relapses are generally treatable. A MALT lymphoma prognostic index, based on age ≥70 years, lactate dehydrogenase levels, and advanced stage, helps to stratify patients according to their event-free survival (EFS) at 5 years.5 Patients with a high MALT prognostic index may also have early disease progression, which clearly correlates with impaired survival.6

Subsequent lines of treatment are needed, as disease activity is often symptomatic and impairs the patient’s quality of life. For this reason, the concept of treatment sequencing is important; providing effective local control of the disease means achieving an acceptable EFS with no (or just a few) harmful side effects. Systemic treatments and chemotherapy are options in multiply relapsing disease, in advanced-stage disease at presentation or relapse, and in cases where initial local treatments have failed.1-4

This review condenses the recommendations offered by the major international guidelines applied in the treatment of MZL and our personal clinical practice and point of view.

Clinical case

A 65-year-old man with a 6-month history of dyspepsia received a diagnosis of histologically documented Helicobacter pylori (HP)–positive gastric MALT lymphoma, appearing as a small, ulcerated lesion of the antrum, in the context of global erythema of the gastric mucosa. No signs of active bleeding were detected. The patient was taking acetylsalicylic acid because of a history of transient ischemic attack. He was also taking valsartan and alfuzosin. His peripheral blood counts were normal, and only a subclinical iron deficiency, without anemia, was identified. Disease staging was accomplished by (1) a total-body computed tomography (CT) scan, which showed no enlarged lymph nodes (either perigastric or distant), with slight thickening of the gastric walls appreciated; (2) endoscopy with ultrasonography to document the involvement of the muscularis propria (stage I; T2 N0 M0); and (3) bone marrow biopsy, which was negative for disease infiltration. He was prescribed a proton pump inhibitor and antibiotics, and his disease status was reevaluated 2 months after treatment. The ulceration had completely resolved, but random gastric biopsies documented persistent disease. He was then referred for gastric radiation therapy.

Treatment sequencing in EMZL

Initial treatment choices in gastric MALT lymphoma

Gastric MALT lymphoma is localized to the stomach and to its tributary nodes most of the time. Disease spread beyond the serous membrane and to adjacent tissue is also possible, as well as concomitant involvement of multiple extranodal sites. Thorough locoregional staging is achieved by endoscopy with ultrasonography, and it is important to rule out the presence of HP. If histopathology is negative, then a stool antigen test or urea breath test is recommended. Initial disease stage (according to the Lugano or Paris staging systems; Table 1) and HP status are the most important parameters considered in any subsequent treatment decisions.7

Staging of gastric MALT lymphoma: a comparison of staging systems and anatomic correlations

| Lugano staging system . | TNM (or Paris) staging system . | Disease extension . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | I1: confined to mucosa or submucosa | T1 N0 M0 | Mucosal or submucosal layer |

| I2: confined to muscularis propria or serosa | T2 N0 M0 | Muscularis propria | |

| T3 N0 M0 | Serosa | ||

| Stage II | II1: extending into abdomen with local nodal involvement | T1-3 N1 M0 | Perigastric lymph nodes |

| II2: extending into abdomen with distant nodal involvement | T1-3 N2 M0 | More distant regional lymph nodes | |

| Stage IIE | Penetration of serosa to involve adjacent organs or tissues | T4 N0 M0 | Adjacent structures |

| Stage IV | Disseminated extranodal involvement or concomitant supradiaphragmatic involvement | T1-4 N3 M0 | Lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm |

| T1-4 N0-3 M1 | Bone marrow invasion, additional extranodal sites | ||

| Lugano staging system . | TNM (or Paris) staging system . | Disease extension . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | I1: confined to mucosa or submucosa | T1 N0 M0 | Mucosal or submucosal layer |

| I2: confined to muscularis propria or serosa | T2 N0 M0 | Muscularis propria | |

| T3 N0 M0 | Serosa | ||

| Stage II | II1: extending into abdomen with local nodal involvement | T1-3 N1 M0 | Perigastric lymph nodes |

| II2: extending into abdomen with distant nodal involvement | T1-3 N2 M0 | More distant regional lymph nodes | |

| Stage IIE | Penetration of serosa to involve adjacent organs or tissues | T4 N0 M0 | Adjacent structures |

| Stage IV | Disseminated extranodal involvement or concomitant supradiaphragmatic involvement | T1-4 N3 M0 | Lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm |

| T1-4 N0-3 M1 | Bone marrow invasion, additional extranodal sites | ||

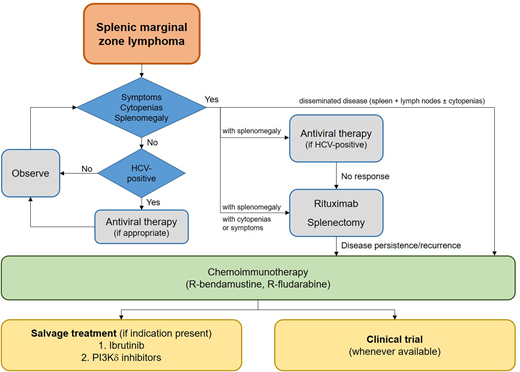

The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines recommend that an HP eradication therapy be administered to all patients with HP+ gastric MALT lymphomas, independent of stage at presentation or histologic grade.3 The same guidelines also suggest antibiotic eradication therapy be given, even in cases of HP− disease, although responses are less likely, as occasional disease regressions have been documented, and the HP test may return a false-negative result. National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend instead that patients with localized disease (stages I and II1, according to the Lugano staging system), meaning lymphoma confined within the gastric walls and perigastric lymph nodes, receive antibiotic therapy if HP+ and, preferentially if lacking the t(11;18) translocation.4 This translocation, found in 15% to 40% of patients with gastric MZL and leading to the juxtaposition of the BIRC3 and MALT1 genes, is a predictor of lack of tumor response to antibiotics.8 Patients with HP− initial-stage disease or with t(11;18), even if HP+, should undergo involved-site radiation therapy (ISRT) or, as a second option, systemic treatment with rituximab. All other presentations of stage IIE disease or higher that indicate spread to more distant nodal structures or to adjacent nodes require a systemic approach if patients are symptomatic (Figure 1). Treatment approaches for localized disease are reviewed briefly below. Systemic treatments for advanced-stage disease or recurrent disease are discussed in “Chemoimmunotherapy in advanced or resistant MALT lymphomas.”

Treatment sequencing in gastric and nongastric MALT lymphoma. *Lugano (or corresponding Paris/TNM [tumor, node, metastasis]) staging system for gastric MZL. **Endoscopy performed during follow-up is always associated with multiple biopsies of gastric mucosa. A shift should be made to the next treatment step when the patient is symptomatic or in cases of overt progression or deeper invasion within gastric walls. Consider repeating antibiotic therapy if HP positivity is still detected. ***Ann Arbor staging system.

Treatment sequencing in gastric and nongastric MALT lymphoma. *Lugano (or corresponding Paris/TNM [tumor, node, metastasis]) staging system for gastric MZL. **Endoscopy performed during follow-up is always associated with multiple biopsies of gastric mucosa. A shift should be made to the next treatment step when the patient is symptomatic or in cases of overt progression or deeper invasion within gastric walls. Consider repeating antibiotic therapy if HP positivity is still detected. ***Ann Arbor staging system.

Antibiotic therapy

Antibiotic therapy is based on the epidemiology of the infection in the patient’s country of residence and should take into account locally expected antibiotic resistance patterns. The most common approach is based on 3 drugs: a proton pump inhibitor with clarithromycin, in combination with amoxicillin or metronidazole for 10 to 14 days.9 The outcome of HP eradication must be confirmed by urea breath test or stool antigen test at least 6 weeks after eradication therapy and at least 2 weeks after withdrawal of the proton pump inhibitor. Response assessment is performed by repeated endoscopy with biopsy. In patients with endoscopic remission of the disease and persistent microscopic lymphoma on histology, it is reasonable to wait at least 12 months before starting a new line of treatment, unless the patient is symptomatic. In case of failure to achieve a meaningful response, a subsequent treatment with ISRT can be considered.3,4 A follow-up endoscopy (with biopsy) is recommended every 3 months in patients with persistent histologic infiltration but no treatment indications, then every 3 to 6 months for 5 years, and then yearly (or when clinically indicated) in those who achieve a complete histologic remission. In case of persistent HP positivity, regardless of the histologic presence of lymphoma, treatment with a course of second-line, non–cross-resistant antibiotics may be attempted.

Radiation therapy

ISRT is the preferred technique in cases of localized disease after failure of antibiotic therapy or HP− localized disease. The International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group recommends that abnormal lymph nodes (sometimes porta hepatis nodes or para-aortic nodes, as well) be encompassed in the clinical target volume. Perigastric nodes are simply included in the treatment volume, although they are not pathologically confirmed to be involved with lymphoma.10 Doses of 24 to 30 Gy to the stomach and perigastric nodes have been effective in local disease control in the long term, without significant toxic effects.11-13

Rituximab

The drug is recommended as a second-line treatment for those in whom antibiotic therapy has failed and who have contraindications to ISRT. The efficacy of 1 treatment per week for 4 consecutive weeks, at the standard dose of 375 mg/m2, as a single agent for gastric and extragastric MALT lymphomas, is reported in retrospective studies.14-16 The studies mainly include patients with extranodal MALT lymphoma in general, and primary gastric disease cases are just a proportion of the entire cohort of patients treated. The only study specifically considering gastric MALT lymphoma15 enrolled 27 patients at any disease stage. In 55% of those, an initial antibiotic eradication therapy or surgery had failed, and 7% were treatment naive. In the remaining cases, chemotherapy was associated with antibiotic eradication therapy or surgery. Objective responses were recorded in 77% of the patients, with a histologic complete response (CR) in 46%, independent of the presence of the t(11;18) translocation. Relapses occurred in only 2 patients within the first 3 years of follow-up. The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group-19 (IELSG) trial, designed to evaluate the efficacy of rituximab+chlorambucil over chlorambucil alone in the treatment of patients with gastric MALT, in whom an initial antibiotic therapy has failed, was amended to include a third arm consisting of single-agent rituximab after the enrollment of the first 252 patients.17 This trial and its results are described in detail in “Chemoimmunotherapy in advanced or resistant MALT lymphomas.”

Surgery

The role of surgery has been questioned, as gastric MALT lymphoma is generally multifocal, thus requiring an extensive (total or subtotal) gastrectomy, usually severely impairing the quality of life. Gastrectomy should be considered as a first-line intervention in cases of life-threatening hemorrhage, gastric perforation, or pyloric stenosis.18

Initial treatment choices in nongastric MALT lymphomas

Nongastric (extragastric) MALT lymphomas can arise in any extralymphatic organ with an anatomically well-structured MALT (such as the gut, the nasopharynx, and the lung) and also at sites normally lacking lymphoid tissue, but with a (temporary) accumulation of B-lymphocytes as a response to chronic stimulation caused by an infection or an autoimmune process. Salivary glands, ocular adnexa, breasts, genitourinary organs, the skin, and the thyroid may be affected by MALT lymphoma in concomitance with some particular conditions, such as Sjögren syndrome or Hashimoto thyroiditis, or as a consequence of certain infections (eg, by Chlamydophila psittaci or Borrelia burgdorferi). It is important to recognize, however, that, in most cases, the etiology is unknown.2,19

Given that this disease may arise at any site and without systemic manifestations, as symptoms are mainly related to the involvement of the affected organ (eg, neck lump or swelling in thyroid MALT lymphoma in a patient with autoimmune thyroiditis, skin nodules, unilateral proptosis or lacrimal gland swelling, or asymmetric parotid swelling), many patients seek a hematologist’s advice after a histologically confirmed diagnosis has been obtained. This implies that, in many instances, surgical intervention, ranging from an excisional biopsy to the removal of an entire organ, if a nonhematologic malignancy is initially suspected, is the first step in the management of the disease.

Available guidelines indicate locoregional treatments such as surgery and radiation therapy as the mainstay of the initial management of localized disease (Ann Arbor stage I and II). The functional and anatomic peculiarities of each affected organ should be considered when choosing among different approaches and during treatment planning, to maximize efficacy and reduce immediate and long-term adverse events.3,4,7,19 Because site-specific guidelines are lacking, our personal view of treatment sequencing in EMZL lymphomas is summarized in Figure 1 and Table 2.

Site-specific extranodal MALT lymphoma treatment

| Site . | First-line, localized disease . | First relapse . | Advanced disease (bilateral or stage IV) . | Notes . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First choice . | Second choice . | ||||

| Skin (single lesion) | Excision or punch; observe in case of negative margins | Radiotherapy (if margins are positive) | Rituximab | Rituximab or R-chemo | — |

| Skin (contiguous) | Radiotherapy | Rituximab | Rituximab or R-chemo | Rituximab or R-chemo | — |

| Skin (multiple) | Rituximab | None | R-chemo | Rituximab or R-chemo | — |

| Parotid | Parotidectomy; observe in case of negative margins | Rituximab (if residual tissue or positive margins) | R-chemo | Rituximab (if bilateral); R-chemo (if systemic) | Limit radiotherapy to reduce xerostomia (especially with Sjögren syndrome) |

| Orbit, lacrimal gland | Radiotherapy | Rituximab | Alternative first-line choice or R-chemo | Rituximab (if bilateral); R-chemo (if systemic) | — |

| Conjunctiva | Rituximab | Radiotherapy | Alternative first-line choice or R-chemo | Rituximab (if bilateral); R-chemo (if systemic) | Published experiences with intralesional rituximab |

| Thyroid | Thyroidectomy (total or partial)+R-chemo | None | R-chemo or targeted agents | R-chemo | Radiotherapy to be avoided to preserve residual thyroid function |

| Lung | Lob(ul)ectomy+ rituximab or rituximab only | None | R-chemo | R-chemo (if bilateral or systemic) | Radiotherapy to be avoided to reduce lung fibrosis; avoid extensive surgery |

| Stomach | Antibiotics (if HP-positive) | Radiotherapy (if HP-negative) or rituximab | Alternative first-line second choice or R-chemo | R-chemo | — |

| Small bowel | Surgical resection+rituximab | None | R-chemo | R-chemo (if multiple lesions detected on CT scan or systemic) | Radiotherapy to be limited |

| Kidney | Nephrectomy (total or partial)+rituximab | None | R-chemo | R-chemo | Use of radiotherapy: to be discussed |

| Breast | Nodulectomy+rituximab or rituximab only | None | R-chemo | R-chemo (if bilateral or systemic) | Use of radiotherapy: to be discussed for unilateral disease |

| Site . | First-line, localized disease . | First relapse . | Advanced disease (bilateral or stage IV) . | Notes . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First choice . | Second choice . | ||||

| Skin (single lesion) | Excision or punch; observe in case of negative margins | Radiotherapy (if margins are positive) | Rituximab | Rituximab or R-chemo | — |

| Skin (contiguous) | Radiotherapy | Rituximab | Rituximab or R-chemo | Rituximab or R-chemo | — |

| Skin (multiple) | Rituximab | None | R-chemo | Rituximab or R-chemo | — |

| Parotid | Parotidectomy; observe in case of negative margins | Rituximab (if residual tissue or positive margins) | R-chemo | Rituximab (if bilateral); R-chemo (if systemic) | Limit radiotherapy to reduce xerostomia (especially with Sjögren syndrome) |

| Orbit, lacrimal gland | Radiotherapy | Rituximab | Alternative first-line choice or R-chemo | Rituximab (if bilateral); R-chemo (if systemic) | — |

| Conjunctiva | Rituximab | Radiotherapy | Alternative first-line choice or R-chemo | Rituximab (if bilateral); R-chemo (if systemic) | Published experiences with intralesional rituximab |

| Thyroid | Thyroidectomy (total or partial)+R-chemo | None | R-chemo or targeted agents | R-chemo | Radiotherapy to be avoided to preserve residual thyroid function |

| Lung | Lob(ul)ectomy+ rituximab or rituximab only | None | R-chemo | R-chemo (if bilateral or systemic) | Radiotherapy to be avoided to reduce lung fibrosis; avoid extensive surgery |

| Stomach | Antibiotics (if HP-positive) | Radiotherapy (if HP-negative) or rituximab | Alternative first-line second choice or R-chemo | R-chemo | — |

| Small bowel | Surgical resection+rituximab | None | R-chemo | R-chemo (if multiple lesions detected on CT scan or systemic) | Radiotherapy to be limited |

| Kidney | Nephrectomy (total or partial)+rituximab | None | R-chemo | R-chemo | Use of radiotherapy: to be discussed |

| Breast | Nodulectomy+rituximab or rituximab only | None | R-chemo | R-chemo (if bilateral or systemic) | Use of radiotherapy: to be discussed for unilateral disease |

First-line treatment choices for localized disease are provided, when appropriate, according to our personal experience. Treatment of first relapse may be based on the approach not previously chosen for first-line treatment (alternative choice). Stage IV (according to Ann Arbor) indicates any dissemination of the disease to any nodal site and/or marrow and/or more than one extranodal site (apart from the initial extranodal site).

R-chemo, chemoimmunotherapy.

Surgery

An initial surgical approach (always necessary for diagnosis), especially if the whole involved organ is removed, may be considered adequate for the treatment of localized EMZL at certain sites, such as lung, breast, thyroid, colon, and small bowel. Surgery alone cannot be considered a definitive therapeutic procedure if margins of resection are involved in disease, in which case, locoregional radiation therapy is strongly recommended. Rituximab monotherapy, discussed later, or systemic chemoimmunotherapy may also be an option.

Radiation therapy

The use of external beam radiation therapy should be thoroughly evaluated, to avoid the irradiation of wide areas of the body and to reduce the incidence of significant morbidity (eg, radiation-induced sicca syndrome in patients with Sjögren syndrome and salivary gland MALT lymphoma and cataract and xerophthalmia in patients with ocular adnexal lymphoma). The dose of radiation varies by site of disease. When treating a salivary gland MZL, the entire parotid (or any of the other involved salivary glands) should be irradiated. The same is done when radiotherapy is chosen as the initial treatment of thyroid MZL. In the treatment of ocular adnexa lymphoma, the clinical target volume includes the entire bony orbit, along with definite or suspected extraorbital extensions. When the disease is limited to the conjunctiva, the clinical target volume includes the entire conjunctival sac and local extensions to the eyelid.10

Low-dose radiation therapy (4 Gy in 2 fractions) is used increasingly in the treatment of localized extranodal indolent lymphomas: although the progression-free survival (PFS) rate with 4 Gy is ∼75% at 5 years, local PFS remains inferior to that obtained with 24 Gy.20 Moreover, significantly more sites of irradiation responded to 24 Gy than did those in the 4-Gy group.

Rituximab

Two phase 2 trials describe the action of rituximab monotherapy in extragastric MALT lymphomas, regardless of stage.14,16 As stated, both trials included patients with gastric and nongastric MALT: skin, salivary glands, lungs, and orbits were the most represented sites. Patients were eligible for enrollment if untreated or if a previous line of treatment had failed (antibiotics, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy). In both trials, rituximab was given at the standard dose of 375 mg/m2 every week, for 4 consecutive weeks. Taken together, the overall response rate (ORR) varied between 67% and 73%, with CR achieved in 17% to 44% of cases. Comparable ORRs were obtained in patients with gastric and nongastric MALT lymphoma (64% vs 80%14 and 67% vs 70%,16 respectively), although neither trial was designed and powered to detect a significant difference. A trend toward better outcomes was seen in treatment-naive patients compared with the previously treated ones, as the median time to treatment failure was 22 months vs 12 months (P = .001) for each cohort, respectively.14 Relapses were common, however: a proportion of patients between 36% and 75% experienced disease relapse after a median follow-up of 15 to 20 months. In their series, the investigators stated that patients were switched to either radiation or chemoimmunotherapy after relapse.14

Single-agent rituximab has also shown efficacy in treatment of cutaneous MZL, particularly in cases with multiple and noncontiguous lesions. In a retrospective study of primary cutaneous indolent B-cell lymphomas, all 5 patients with MZL obtained a response, with a CR in 4 cases.21

Back to the clinical case

Two years later, a follow-up CT scan showed the appearance of a solid and irregular nodular lesion of the right upper lobe. The patient was well and did not report any symptoms. No lymph nodes were detected at the hilar or mediastinal sites or at any other significant site. A positron-emission tomography scan showed positive uptake of the nodule, without any other pathologic finding. An adequate amount of tissue was collected via transbronchial fine-needle biopsy, and a diagnosis of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma was made. Endoscopy showed a macroscopically normal gastric mucosa, and random biopsies excluded the recurrence of marginal zone lymphoma.

What was the most suitable treatment strategy?

Systemic immunochemotherapy was prescribed, with rituximab+bendamustine given for 6 cycles. A CR was achieved at the end of the treatment program.

Chemoimmunotherapy in advanced or resistant MALT lymphomas

As a rule, systemic chemoimmunotherapy should be considered in cases of advanced-stage disease and in cases of persistent or recurrent lymphoma after treatment with radiotherapy or single-agent rituximab, if it occurs locally or spreads systemically.3,4 Advanced-stage disease indicates lymphoma dissemination to adjacent organs and tissues (Lugano stage IIE for gastric MALT lymphoma), to distant lymph nodes (Lugano stage II2 and Ann Arbor stage IV), bilaterally to an extranodal site (eg, lungs and parotid glands), or to the bone marrow or any other extranodal organ (Lugano and Ann Arbor stage IV). Chemoimmunotherapy should be initiated when a strict indication for treatment is present, as it is generally effective for any indolent lymphoma. Indications for systemic treatment include gastrointestinal bleeding, presence of systemic lymphoma-related symptoms, threatened end-organ function, bulky masses, and steady or rapid progression. If no indication is present, advanced disease should be managed conservatively, and close monitoring should be established.4 Chemoimmunotherapy is also the mainstay of the management of disease transformation into aggressive B-cell lymphoma. In this case, specific drug combinations active in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas should be taken into account [eg, rituximab+cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP)].

Very few drugs have been directly tested in MZLs: most of the experience comes from trials that enrolled patients with indolent B-cell lymphomas in general. Alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, and bendamustine) or purine nucleoside analogues (fludarabine and cladribine) have shown efficacy in this context. An extensive review of chemotherapy-containing regimens in MALT lymphomas has been published.22 Table 3 reports experiences in gastric MALT lymphoma.23-26

Chemotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy outcomes in gastric MALT lymphoma

| Study . | Patients . | Early stage, % . | Treatment . | Outcomes, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hammel et al23 | 24 | 71 | Cyclophosphamide or chlorambucil | 75 CR |

| Avilés et al24 | 83 | 100 | CHOP×3 + CVP×4 | 100 CR |

| Jäger et al25 | 19 | 100 | Cladribine | 100 CR |

| Salar et al26 | 21 | 64 | Bendamustine+rituximab | 94 CR; 6 PR |

| Zucca et al17 | 53 | — | Rituximab+chlorambucil | 91 CR |

| 57 | — | Chlorambucil | 61 CR | |

| 61 | — | Rituximab | 67 CR |

| Study . | Patients . | Early stage, % . | Treatment . | Outcomes, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hammel et al23 | 24 | 71 | Cyclophosphamide or chlorambucil | 75 CR |

| Avilés et al24 | 83 | 100 | CHOP×3 + CVP×4 | 100 CR |

| Jäger et al25 | 19 | 100 | Cladribine | 100 CR |

| Salar et al26 | 21 | 64 | Bendamustine+rituximab | 94 CR; 6 PR |

| Zucca et al17 | 53 | — | Rituximab+chlorambucil | 91 CR |

| 57 | — | Chlorambucil | 61 CR | |

| 61 | — | Rituximab | 67 CR |

The IELSG-19 trial is to date the largest randomized trial to show the superiority of a rituximab-containing regimen over monotherapy in extranodal MALT lymphoma.17 Initially designed as a phase 3 trial randomizing patients to rituximab+chlorambucil or chlorambucil alone in a 1:1 fashion, it was amended to include a third arm consisting of single-agent rituximab, and the enrollment ratio was changed at that point to 1:1:6. Patients with extranodal MALT lymphoma, either at diagnosis or after failure of a prior local therapy were eligible for the study. Of the patients eligible for final analysis (n = 401), 8% had received prior local therapy (surgery, radiation therapy, and antibiotics), 44% had advanced-stage disease (Ann Arbor stage III-IV), with nodal involvement in 35% of those cases and bone marrow involvement in 18%. Patients’ clinical characteristics were all well-balanced between treatment arms. Chlorambucil was given daily at 6 mg/m2 for 42 consecutive days (6 weeks), then resumed at the same dose for 2 weeks with 4-week intervals for up to 4 months (maintenance treatment, if at least a stable disease was obtained). Rituximab was given at a standard dose of 375 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, 15, and 22, then on day 1 of each cycle for maintenance. Patients receiving single-agent rituximab did so on the schedule used for combination therapy. Treatment with the rituximab+chlorambucil combination produced better responses than chlorambucil alone (ORR, 95% vs 85%; CR rate, 79% vs 63%), as reported earlier.27 Rituximab alone produced an outcome that was similar to chlorambucil alone (ORR 78%; CR rate 56%), with a 5-year EFS of 68%, 51%, and 50% for patients treated with the combination, with chlorambucil alone, or single-agent rituximab, respectively.17 Despite the demonstrated superior efficacy of the combination regimen, longer overall survival (OS) rates were not appreciated, most likely because of effective salvage treatment options in this indolent disease. Although EFS was inferior with single-agent rituximab, the lack of OS differences among treatment arms reinforces its role in the initial treatment of extranodal MALT lymphomas, as its application may delay the toxic effects related to chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

The addition of rituximab to bendamustine (the latter given at a dose of 90 mg/m2) produced significant results in a phase 2 prospective trial.26 The trial enrolled 60 patients (57 evaluable) with untreated extranodal MALT lymphoma (any stage) in need of systemic treatment, patients with gastric MALT with active disease after HP-eradicating treatment, and patients with cutaneous MZL in whom initial local treatment had failed. Treatment was given in 4 cycles if the patient achieved an early CR after the third course or in 6 cycles if the patient was in partial response at midtreatment evaluation. The regimen produced an ORR of 100% with CR in 98% of the cases, with no significant differences according to the primary site of disease (gastric vs nongastric). As 75% of patients achieved a CR after only 3 cycles, treatment duration was 4 months in most instances. The 7-year EFS and PFS were 88% and 93%, respectively; outcomes were not significantly different according to disease localization.28 Our institutional experience with rituximab and bendamustine in MALT and non-MALT MZLs yielded similar results.29

Fludarabine-containing regimens have also demonstrated their efficacy in the treatment of MZL, including extranodal MALT lymphomas with advanced-stage presentation and need for treatment. A retrospective experience from our group with the rituximab-fludarabine-mitoxantrone regimen in indolent nonfollicular lymphomas included 49 patients with MALT lymphoma: we recorded an ORR of 96%, with a CR rate of 90% and a disease-free survival rate at 10 years >90%.30 In a homogeneous cohort of 17 patients with bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma from our institution, treated with the rituximab-fludarabine-mitoxantrone regimen (10 patients) or with fludarabine-mitoxantrone (7 patients), the ORR was 100%, with a CR in 82% of the cases, with an OS of 100% and a PFS of 71% at 14 years. No comparisons could be made between rituximab-treated and untreated patients because of the small sample.31 Importantly, however, fludarabine-based regimens have been increasingly abandoned in the treatment of indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, given the associated risk of secondary malignant disease. For this reason, their use should follow a careful risk-benefit evaluation.

Treatment sequencing in SMZL

Treatment should be established in symptomatic patients with SMZL with massive splenomegaly causing pain, early satiety, or cytopenia, defined as hemoglobin < 10.0 g/dL, platelets < 80 × 103/microL, or neutrophils < 1 × 103/microL. Asymptomatic patients may be followed clinically without intervention for many years, given that treatment does not influence survival.3 Autoimmune manifestations, such as autoimmune hemolytic anemia or immune thrombocytopenia, are not infrequent in patients with SMZL and may complicate the course of the disease, even if proper treatment criteria are absent. They should be promptly diagnosed and specifically treated. Single-agent rituximab may be useful in this regard.32 In patients with concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection who do not need immediate treatment, antiviral therapy should be considered, if feasible, and appropriate hepatology consultation is advised.33,34 Rituximab and splenectomy are the recognized first-line treatment options in symptomatic patients. Chemoimmunotherapy is an option in case of first-line treatment failure (Figure 2).

Splenectomy

Surgery is traditionally considered the initial treatment for SMZL with massive and symptomatic splenomegaly and peripheral cytopenias. It rapidly corrects anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia, when it is related to hypersplenism, and removes the dominant focus of the disease.35 Evidently, such management does not influence marrow infiltration or blood lymphocytosis. Postsplenectomy remissions are generally stably maintained for years, with PFS and OS rates of 50% to 60% and 70% to 80%, respectively, and patients can remain asymptomatic for very long periods, with a median time to the next treatment of 8 years.36 Importantly, however, not all patients are deemed eligible for splenectomy, which is contraindicated in cases with disease dissemination to distant lymph nodes or other parenchymas, as well as those in which cytopenias are secondary to massive bone marrow infiltration and are not believed to be correctable by splenectomy alone. It must be noted that splenectomy is a major surgical procedure, with potential acute and late complications. Vaccinal prophylaxis against capsulated bacteria is always necessary.37 Splenectomy also has the advantage of ruling out a possible histologic transformation, which can be suspected in cases with rapid spleen enlargement, elevation of lactate dehydrogenase, or appearance of systemic symptoms.

Rituximab

Rituximab, used as a single agent or combined with chemotherapy, is highly effective in this subgroup of patients and is preferred in comparison with splenectomy by some clinicians.36,38-41 Single-agent rituximab (375 mg/m2 weekly for 4-8 weeks) produces rapid responses, with an ORR of 88% to 100%, CR in nearly 45% to 90% of cases, and a 10-year PFS that may exceed 60%.36 It also remains active in cases with disease relapse.

Chemoimmunotherapy

Chemoimmunotherapy regimens are based on rituximab combined with alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide or bendamustine), anthracyclines, or fludarabine.36 This approach is particularly indicated in cases of disseminated disease at presentation with clinical symptoms, as well as in patients who are unresponsive to first-line therapy or have disease recurrence. Available data are from retrospective experiences involving a limited number of patients with the application of various combinations of drugs and treatment schedules. For this reason, comparison of published series is risky, and none of the described regimens can be deemed the gold standard. Reported ORRs are higher than 80%, with CR in more than half of the treated patients and long response durations, however with not negligible toxicity, especially infections. The BRISMA (Italian Lymphoma Foundation; FIL/IELSG-36) study has recently investigated the efficacy of the combination of rituximab+bendamustine in 56 SMZL patients with symptomatic disease, who were ineligible for splenectomy and had not responded to HCV-directed antiviral treatment.42 Bendamustine was given at a dose of 90 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 in cycles of 28 days, for 6 cycles. The ORR rate was 91% and the CR rate was 73%, with 3-year PFS and OS of 90% and 96%, respectively. Toxicity was mostly hematologic, with grade 3-4 neutropenia recorded in 43% of patients, which compares favorably with a previous Italian experience with rituximab with cyclophosphamide, liposomal doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-COMP) in the same subset of patients.43 Based on the results in B-cell indolent lymphomas,44,45 we suggest the rituximab+bendamustine combination be used as the frontline treatment in patients with disseminated disease (splenomegaly and distant nodal involvement) in need of therapy and as a salvage regimen after failure of single-agent rituximab or splenectomy.

Treatment sequencing in NMZL

Guidelines recommend that NMZL be treated as any other indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma with lymph node involvement, according to the principles applied in follicular lymphoma.3,4,46

Rituximab and radiotherapy

In patients with limited-stage disease (stage I or contiguous stage II, according to Ann Arbor), ISRT or rituximab monotherapy (after surgical excision of the affected lymph node for diagnostic purposes) is often appropriate. Single-agent rituximab is also a valuable first-line option in cases of noncontiguous stage II disease; chemoimmunotherapy is a suitable alternative. Observation may also be adequate in these cases if the potential toxicity of a systemic approach outweighs the expected clinical benefit.

Chemoimmunotherapy

Chemoimmunotherapy is indicated in patients with symptomatic (high tumor burden), advanced-stage disease. In contrast, a watchful-waiting policy is adopted if the tumor burden is low, although the disease is disseminated. Rituximab+bendamustine,44,45 rituximab+fludarabine,30 and rituximab+cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone±anthracyclines (R-CHOP/R-CVP) are the most widely used regimens. Rituximab maintenance after induction is optional, as there is no evidence from prospective studies of any benefit over observation only, if frontline therapy was successful. Chemoimmunotherapy is also indicated for disease progression or when radiotherapy or rituximab therapy fail. Lymph node biopsy is always recommended at disease relapse to rule out the possibility of histologic transformation.

Autologous stem cell transplantation

The role of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in patients with MZL was investigated in a retrospective study by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, the Italian Lymphoma Foundation and the Italian Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation.47 The study involved 199 patients with nontransformed NMZL (55 patients), MALT lymphoma (111 patients), and SMZL (33 patients), with a median age at transplantation of 56 years. The median number of prior therapies was 2; patients had chemosensitive disease at the time of conditioning, which was chemotherapy-based in 89% of the cases. A trend toward performing more ASCTs in non-MALT MZL has been noted in more recent years. After a median follow-up of 5 years, the 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse-progression and nonrelapse mortality was 38% and 9%, respectively. Five-year EFS and OS were 53% and 73%, respectively. The much higher OS compared with EFS indicates that patients experiencing ASCT failure can still be salvaged, especially in this era of new drugs. This observation is of importance, because it indicates that the role of ASCT in treatment sequencing for MZL needs further clarification. For this reason, we consider high-dose therapy and ASCT only for young patients with aggressive presentations and short duration of remission after standard immunochemotherapy regimens, and mainly for those with nodal disease.

Immunomodulators, targeted agents, and new drugs under development

Systemic approaches with targeted agents, used either as single agents or in combination with immunotherapy, represent a step forward in the optimization of treatment of patients for whom conventional immunochemotherapy is unsuitable and in cases of relapsed or refractory disease.48 Enrollment of patients in clinical trials exploring new agents is always desirable when standardized treatment strategies are unavailable. A complete survey of agents being explored in clinical trials is beyond the scope of this article. We provide a review of the existing results with agents we usually apply in patients who experience multiple relapses and meet treatment requirements (Table 4). It is important to note that most of these agents are not formally approved worldwide, as data are generated from subgroup analyses or derived from monocentric experiences.

Experiences with targeted and novel agents in marginal zone lymphomas

| Study . | Drug . | Setting . | Patients . | ORR % . | CR % . | Median PFS, mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanazzi et al49 | 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan | MALT relapsed | 30 | 90 | 77 | Not reached* |

| Samaniego et al50 | 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan | MALT de novo | 11 | 100 | — | Not reached |

| Lossos et al51 | 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan | MZL de novo | 16 | 88 | 56 | 47.6 |

| Lolli et al 52 | 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan | MALT de novo+relapsed | 16 | 94 | 63 | 37.3 |

| Zinzani et al 53 | Chemotherapy+90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan | MZL de novo | 10 | 90 | 90 | — |

| Kiesewetter et al 55 | Lenalidomide | MALT de novo+relapsed | 18 | 61 | 33 | — |

| Kiesewetter et al 56 | Lenalidomide+rituximab | MALT de novo+relapsed | 46 | 80 | 54 | — |

| Becnel et al 59 | Lenalidomide+rituximab | MZL de novo | 30 | 93 | 70 | 59.8 |

| Noy et al 61 | Ibrutinib | MZL relapsed | 63 | 48 | 3 | 14.2 |

| Gopal et al 62 | Idelalisib | MZL relapsed | 15 | 47 | 7 | 7.0 |

| Flinn et al 63 | Duvelisib | MZL relapsed | 18 | 39 | — | — |

| Dreyling et al 64 | Copanlisib | MZL relapsed | 23 | 70 | 9 | — |

| Forero-Torres et al 65 | Parsaclisib | MZL relapsed | 9 | 78 | 33 | — |

| Zinzani et al 66 | Umbralisib | MZL relapsed | 69 | 55 | 10 | 71%† |

| Study . | Drug . | Setting . | Patients . | ORR % . | CR % . | Median PFS, mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanazzi et al49 | 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan | MALT relapsed | 30 | 90 | 77 | Not reached* |

| Samaniego et al50 | 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan | MALT de novo | 11 | 100 | — | Not reached |

| Lossos et al51 | 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan | MZL de novo | 16 | 88 | 56 | 47.6 |

| Lolli et al 52 | 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan | MALT de novo+relapsed | 16 | 94 | 63 | 37.3 |

| Zinzani et al 53 | Chemotherapy+90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan | MZL de novo | 10 | 90 | 90 | — |

| Kiesewetter et al 55 | Lenalidomide | MALT de novo+relapsed | 18 | 61 | 33 | — |

| Kiesewetter et al 56 | Lenalidomide+rituximab | MALT de novo+relapsed | 46 | 80 | 54 | — |

| Becnel et al 59 | Lenalidomide+rituximab | MZL de novo | 30 | 93 | 70 | 59.8 |

| Noy et al 61 | Ibrutinib | MZL relapsed | 63 | 48 | 3 | 14.2 |

| Gopal et al 62 | Idelalisib | MZL relapsed | 15 | 47 | 7 | 7.0 |

| Flinn et al 63 | Duvelisib | MZL relapsed | 18 | 39 | — | — |

| Dreyling et al 64 | Copanlisib | MZL relapsed | 23 | 70 | 9 | — |

| Forero-Torres et al 65 | Parsaclisib | MZL relapsed | 9 | 78 | 33 | — |

| Zinzani et al 66 | Umbralisib | MZL relapsed | 69 | 55 | 10 | 71%† |

Time-to-treatment failure.

†PFS percentage at 12 months.

Radioimmunotherapy

The most significant experience with single-agent 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan (90Y-IT) radioimmunotherapy in relapsed or refractory EMZL is reported in a prospective Italian trial with 30 patients,49 17 affected by extragastric MALT lymphoma (including skin, orbit and conjunctiva, soft tissues, parotid, liver, and kidney) and 13 by HP− gastric MALT lymphoma, all of whom had undergone at least 1 treatment (including radiation or surgery). High response rates were reported (90%), with 23 (77%) patients achieving a CR. Only 2 CR patients had a relapse, whereas all the remaining ones maintained their status for at least 3 years.

Samaniego et al50 and Lossos et al51 investigated the activity of 90Y-IT in untreated patients. Both studies reported high response rates (at least 90%), with median PFS durations exceeding 4 years. Similar results with 90Y-IT have been reported recently by our group52 in a series of both untreated and pretreated patients with EMZL: 94% of patients responded to radioimmunotherapy, with CR achieved in 63% of the cases; 45% of the treated patients were free of disease at 4 years.

The efficacy of radioimmunotherapy as consolidation after chemotherapy in untreated patients with indolent lymphoma, including 10 untreated MZL, was reported in 2008 by our group. 90Y-IT was given after 6 cycles of fludarabine+mitoxantrone and 2 doses of rituximab (250 mg/m2, 7 days before and immediately before the administration of 90Y-IT). 90Y-IT is appropriate for patients achieving at least a partial response after chemotherapy, with a bone marrow disease infiltration <25% of the cellularity and a platelet count ≥100 × 103/microL. All but 1 patient with MZLs successfully obtained a CR at the end of the treatment.53

Promising results with β-lutin, a murine anti-CD37 antibody conveying the β-emitter 177Lu are now emerging with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma and patients with MZL, with responses in nearly 60% of the cases and CR in up to 28%.54

Lenalidomide, with or without rituximab

Kiesewetter et al reported initial data on single-agent lenalidomide, given at a dose of 25 mg/day for 21 consecutive days in patients with untreated or relapsed nongastric MALT lymphoma and HP− gastric MALT lymphoma, that were consistent with an ORR of 61% and a CR rate of 33%.55 Responses were seen in both treatment-naive and pretreated patients, and conversions to better responses were documented with continuous therapy in nearly 40% of patients. The same group demonstrated the activity of lenalidomide (20 mg/d for 21 days) and rituximab (375 mg/m2 on day 1 of each cycle for 6 cycles) in 46 patients with extranodal MALT lymphoma. One quarter of the patients had received prior systemic treatment, and nearly 40% had disseminated disease at presentation. The combination demonstrated an ORR of 80% and a CR rate of 54%, along with a favorable toxicity profile.56 Based on their experience with lenalidomide in MZL, the investigators reported that at least half of the patients were relapse free at a median follow-up of 68 months, with a median PFS of 72 months. According to their experience, patients with primary extragastric disease had better outcomes than those with primary gastric MALT lymphoma. They found no differences in PFS according to disease stage or previous systemic therapy, although there were limitations related to the number of patients included in their series.57 In the experience reported by the MD Anderson Cancer Center in 30 previously untreated advanced-stage MZL patients, lenalidomide+rituximab (same schedule as in Kiesewetter et al, with possible treatment extension of lenalidomide only for 6 more cycles if patients were responding) produced an ORR of 93%, with a CR rate of 70% and a median PFS of 60 months at a median follow-up of 75 months.58,59 Although generated from small cohorts of patients and from subgroup analyses of larger trials involving patients with multiple indolent histologies, these data suggest that lenalidomide and rituximab may represent an attractive chemotherapy-free treatment to be offered to patients with MZL during either induction or salvage treatment.

The improved efficacy of the combination of lenalidomide+rituximab over rituximab+placebo has been confirmed in a phase 3 randomized trial with 358 patients with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma, with a median PFS of 39.4 months vs 14.1 months for each treatment arm.60

Ibrutinib

The efficacy and safety of ibrutinib in relapsed and refractory MZL have been demonstrated in a phase 2 study involving 63 patients. Nearly half of them had extranodal measurable lymphoma lesions: 22% had SMZL, and 22% had NMZL. Ibrutinib dosing was 560 mg once daily until progression or unacceptable toxicity. In 60 evaluable patients, the ORR was 48%, with a CR in 3% of patients. At a median follow-up of 19.4 months, the median duration of response was not reached, and the median PFS was 14.2 months.61 These data constituted the rationale for the United States Food and Drug Administration’s approval of ibrutinib for the treatment of patients with MZL in need of therapy, in whom at least 1 prior anti-CD20 therapy has failed.

PI3K inhibitors

The blockade of the phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway seems highly promising for the treatment of relapsed or refractory MZLs. Several drugs now commercially available all inhibit the PI3Kδ isoform with different selectivity.62-66 Idelalisib, duvelisib, copanlisib, and, more recently, parsaclisib and umbralisib have all been tested in clinical trials enrolling patients with pretreated indolent lymphomas, mostly follicular lymphoma, among which patients with MZL represented a small subset. These agents are all effective, as objective responses are seen in a proportion of cases varying from 47% to 78%, but the achievement of a CR is infrequent (7% to 33%), sometimes with relevant toxicity in terms of infections, inflammatory adverse events, or metabolic alterations.

Back to the clinical case

After 18 months, multiple nodular lesions were detected in both lungs on high-resolution CT scan, all with pathologic uptake in a positron emission tomography scan. A transthoracic biopsy of the largest nodule confirmed the diagnosis of MALT lymphoma. No extrathoracic evidence of disease was found.

Which salvage treatment can be started?

The patient was started on ibrutinib, obtaining a partial response after 4 months. At this writing, treatment was still ongoing, without significant side effects.

Conclusions

MZLs are indolent diseases with long survival rates but a high tendency to relapse over time. Extranodal disease is frequently confined to a single organ or site, even in cases with recurrence. SMZL, if asymptomatic, may be followed up without treatment for years. NMZL is often disseminated at presentation and requires treatment if advanced-stage disease is accompanied by high tumor burden.

Sequential application of various treatments is the key to success in the treatment of MZL. On the one hand, this strategy is necessary to preserve adequate organ function and avoid excess toxicity, as systemic treatment is limited to advanced symptomatic or recurrent disease. On the other hand, this approach increases survival rates. New drugs and targeted agents offer treatment opportunities in highly pretreated individuals and in particular categories of patients, often limiting the need for repeated application of cytotoxic drugs.

Correspondence

Pier Luigi Zinzani, Institute of Hematology, “L. e A. Seràgnoli,” University of Bologna, Via Massarenti, 9-40138 Bologna, Italy; e-mail: pierluigi.zinzani@unibo.it.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

![Treatment sequencing in gastric and nongastric MALT lymphoma. *Lugano (or corresponding Paris/TNM [tumor, node, metastasis]) staging system for gastric MZL. **Endoscopy performed during follow-up is always associated with multiple biopsies of gastric mucosa. A shift should be made to the next treatment step when the patient is symptomatic or in cases of overt progression or deeper invasion within gastric walls. Consider repeating antibiotic therapy if HP positivity is still detected. ***Ann Arbor staging system.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/hematology/2020/1/10.1182_hematology.2020000157/4/m_hem2020000157cf1.png?Expires=1767699784&Signature=NrDruWDMAd5ib4qWP5hlem2ha3zBpAadMpS~~F94XTBR9P5-IsHel2Y4FqLR69vUgr9VRqYn95s2hXZDL4TvTYX6e7sC0ALrw3KRcauh~EuTVKekrC~Nw~5RGlGpO7g-y2yHbEcbpd36vHiByJQZi9gJr2srzH07QhgFqTxokQ0cmwoRylxiczTdOCC8uOI6vsBzF02djvmOeRsN~9IpcGtFxbZFQBwLY2KRfnXEwjMOR-IKTrrJVXexL37rAP1UBA1gFz25d-Omujvyz14NqYdsRu2-BI0Tya1EQB6ChxnUR2XcYQsOephe0lUbYshBX2ZCwInRzSTuI~nbMJ4IMw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)