Abstract

Hematologists are often consulted for thrombocytopenia in pregnancy, especially when there is a concern for a non-pregnancy-specific etiology or an insufficient platelet count for the hemostatic challenges of delivery. The severity of thrombocytopenia and trimester of onset can help guide the differential diagnosis. Hematologists need to be aware of the typical signs of preeclampsia with severe features and other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy to help distinguish these conditions, which typically resolve with delivery, from other thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs) (eg, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura or complement-mediated TMA). Patients with chronic thrombocytopenic conditions, such as immune thrombocytopenia, should receive counseling on the safety and efficacy of various medications during pregnancy. The management of pregnant patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia who are refractory to first-line treatments is an area that warrants further research. This review uses a case-based approach to discuss recent updates in diagnosing and managing thrombocytopenia in pregnancy.

Learning Objectives

Use the trimester of presentation and severity of thrombocytopenia to help guide the differential diagnosis

Identify features of preeclampsia with severe features vs other thrombotic microangiopathies in pregnancy

Describe management options for chronic immune thrombocytopenia in pregnancy

Introduction

Thrombocytopenia occurs in up to 10% of pregnancies, with etiologies ranging from the benign to life-threatening.1 As obstetricians are experts in managing the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (eg, preeclampsia [PEC]), a hematology consult often signals the patient has atypical features for these disorders. Hematologists are also consulted for treatment recommendations in patients with preexisting chronic thrombocytopenia. This review presents 2 cases highlighting an approach to managing these challenging consults.

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 32-year-old primigravida woman at 34 weeks gestation presents with abdominal pain. Her blood pressure is elevated at 150/90 mm Hg. Her platelet count has dropped to 80 × 109/L from 150 × 109/L 2 months prior. White blood cell count is 4.0 × 109/L and hemoglobin is 9 g/dL.

Initial evaluation of thrombocytopenia presenting in pregnancy

An initial laboratory workup includes review of a peripheral blood smear (evaluating for pseudothrombocytopenia and any morphologic abnormalities) and an assessment of renal and hepatic function. Hematologists should consider both “pregnancy-specific” and “general” causes of thrombocytopenia (Table 1).2 Similar to nonpregnant patients, current medications and comorbidities should be reviewed as potential culprits. It is essential to inquire about the presence of any neurologic, infectious, or B-symptoms. A history of thrombocytopenia during prior pregnancies or family history of thrombocytopenia can be revealing.3 On physical examination, special attention must be paid to any elevation in blood pressure, bruising, hepatosplenomegaly, or lymphadenopathy.3 Additional complete blood count abnormalities significantly change the differential, with possible exceptions for thrombocytopenia with concomitant mild anemia due to increased plasma volume in the later trimesters (physiologic anemia) or a microcytic anemia (iron deficiency). These generally mild anemias are common in pregnancy and may be unrelated to the underlying etiology of the thrombocytopenia.4 Pancytopenia warrants a bone marrow biopsy if an offending medication and/or vitamin deficiency cannot be identified.5

Examples of pregnancy-specific causes and general causes for thrombocytopenia during pregnancy

| Pregnancy specific |

| Gestational thrombocytopenia |

| Preeclampsia with severe features |

| Eclampsia |

| HELLP |

| Acute fatty liver of pregnancy |

| General* |

| Immune thrombocytopenia |

| Hereditary thrombocytopenia |

| Type 2B von Willebrand disease |

| Drug-induced thrombocytopenia |

| Infections |

| Cirrhosis |

| Splenomegaly |

| Bone marrow disorders (eg, aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, leukemia/lymphoma) |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria |

| Complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy |

| TTP |

| Autoimmune disorders (eg, lupus, antiphospholipid syndrome) |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| Pregnancy specific |

| Gestational thrombocytopenia |

| Preeclampsia with severe features |

| Eclampsia |

| HELLP |

| Acute fatty liver of pregnancy |

| General* |

| Immune thrombocytopenia |

| Hereditary thrombocytopenia |

| Type 2B von Willebrand disease |

| Drug-induced thrombocytopenia |

| Infections |

| Cirrhosis |

| Splenomegaly |

| Bone marrow disorders (eg, aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, leukemia/lymphoma) |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria |

| Complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy |

| TTP |

| Autoimmune disorders (eg, lupus, antiphospholipid syndrome) |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

Table based on Gernsheimer et al.2

List of examples diagnoses to consider, not inclusive of all possible diagnoses.

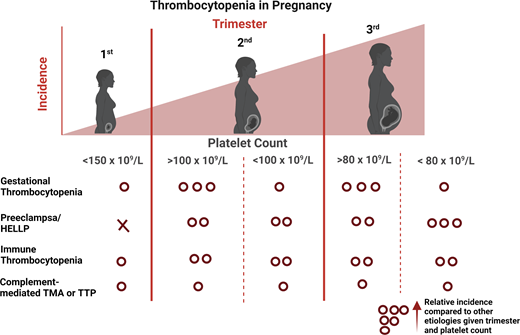

Differential diagnosis by severity of thrombocytopenia and trimester of onset

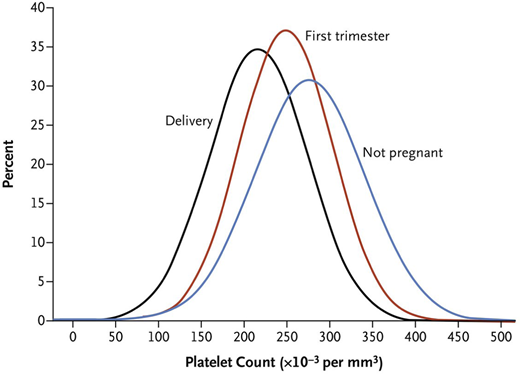

Knowledge of the expected platelet count trend during pregnancy is important to distinguish benign from life-threatening etiologies. A study by Reese et al1 of ~7000 pregnant vs nonpregnant individuals showed platelet counts were lower during pregnancy, beginning in the first trimester, and lowest at time of delivery (Figure 1). This benign phenomenon of steadily decreasing platelet counts throughout pregnancy with spontaneous recovery in the nonpregnant state is known as gestational thrombocytopenia (GT). It is believed to be partly due to hemodilution secondary to increased plasma volume and splenic sequestration.6 However, the degree of thrombocytopenia is important to consider before invoking GT as the cause. Platelet counts at delivery <100 × 109/L occur in 1% and <80 × 109/L in only 0.1% of women with uncomplicated pregnancies.1 Given the rarity of this degree of thrombocytopenia in uncomplicated pregnancies, platelets <100 × 109/L warrant careful consideration of etiologies other than GT.1

Platelet count distribution. Shown are mean platelet counts of the non-pregnant women and the distribution of the mean platelet counts during first trimester and at time of delivery in women who had uncomplicated pregnancies. From N Engl J Med, Reese et al,1 Platelet Counts During Pregnancy, 379, 32-43. Copyright © 2018 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

Platelet count distribution. Shown are mean platelet counts of the non-pregnant women and the distribution of the mean platelet counts during first trimester and at time of delivery in women who had uncomplicated pregnancies. From N Engl J Med, Reese et al,1 Platelet Counts During Pregnancy, 379, 32-43. Copyright © 2018 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

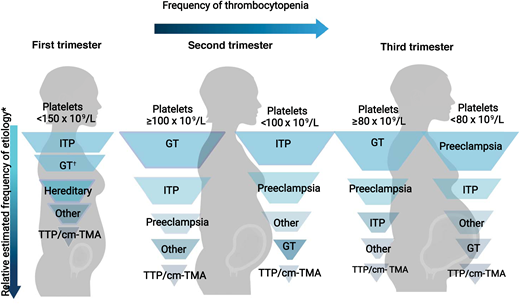

The trimester of onset of the thrombocytopenia is also helpful in determining the etiology (Figure 2).3 In the first trimester, only 1.8% of patients with uncomplicated pregnancies have a platelet count <150 × 109 L. This increases to 4.8% and 8.5% in the second and third trimesters, respectively.1 Thus, GT most commonly becomes apparent in the later trimesters.1,3 On the differential for isolated thrombocytopenia in the first trimester is hereditary thrombocytopenia, immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), and, more rarely, type IIB von Willebrand disease (a diagnosis to consider in a patient with a personal and/or family history of bleeding as the associated coagulopathy may complicate delivery).7 The hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (eg, PEC and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets [HELLP]) present after 20 weeks (mid to late second trimester), with most occurring after 34 weeks (third trimester).8

Relative frequency of etiology of thrombocytopenia during pregnancy by trimester. Relative frequency estimated based on review of literature and experience as described in Cines and Levine3 includes infection, disseminated intravascular coagulation, drug-induced thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow failure.

*In a study by Reese et al,1 1.8% of women with uncomplicated pregnancies had platelets <150 × 109/L. Gestational thrombocytopenia was far more common in the second or third trimesters.

Relative frequency of etiology of thrombocytopenia during pregnancy by trimester. Relative frequency estimated based on review of literature and experience as described in Cines and Levine3 includes infection, disseminated intravascular coagulation, drug-induced thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow failure.

*In a study by Reese et al,1 1.8% of women with uncomplicated pregnancies had platelets <150 × 109/L. Gestational thrombocytopenia was far more common in the second or third trimesters.

CLINICAL CASE 1 (Continued)

A peripheral blood smear reveals no platelet clumping and 2 to 3 schistocytes per high-power field. Creatinine is elevated at 1.7 mg/dL (baseline creatinine, 1.0 mg/dL). Liver function is within normal limits, except for an elevated total bilirubin at 1.9 mg/dL. Lactate dehydrogenase is elevated at 600 I U/L.

Differential diagnosis for thrombocytopenia with microangiopathyic hemolytic anemia during pregnancy

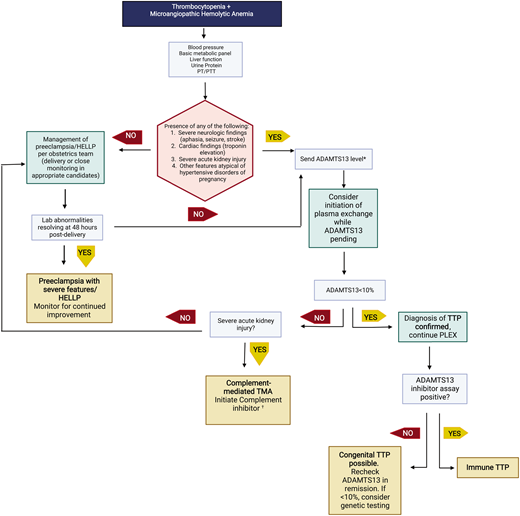

The presence of schistocytes and elevated lactate dehydrogenase supports the diagnosis of a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia with thrombocytopenia is concerning for a thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). Table 2 outlines features of TMAs that may present during pregnancy. It is of utmost importance for hematologists to recognize differences between PEC with severe features/HELLP and thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP)/complement-mediated TMA (cm-TMA) as their management differs greatly (with urgent delivery indicated only for the former). A brief schema for evaluating a TMA during second and third trimesters of pregnancy is shown in Figure 3. For an in-depth review, we refer readers to recent an international working group report by Fakhouri et al.9

Evaluation of thrombotic microangiopathies presenting in the second and third trimesters. This schema highlights recommended testing to distinguish preeclampsia with severe features/HELLP from cm-TMA or TTP. Not all possible etiologies to consider are listed in this brief schema.

*ADAMTS13 testing may also be appropriate in patients with clinical picture consistent with HELLP syndrome to rule out TTP as an alternate etiology. †Other etiologies to consider with severe renal injury are severe hypertension or catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome.

PT/PTT, prothrombin/partial thrombplastin time.

Evaluation of thrombotic microangiopathies presenting in the second and third trimesters. This schema highlights recommended testing to distinguish preeclampsia with severe features/HELLP from cm-TMA or TTP. Not all possible etiologies to consider are listed in this brief schema.

*ADAMTS13 testing may also be appropriate in patients with clinical picture consistent with HELLP syndrome to rule out TTP as an alternate etiology. †Other etiologies to consider with severe renal injury are severe hypertension or catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome.

PT/PTT, prothrombin/partial thrombplastin time.

Clinical and laboratory features of pregnancy-specific TMAs, nonpregnancy specific TMAs, and DIC

| . | Preeclampsia with severe features/HELLP . | AFLP . | TTP . | cm-TMA . | DIC . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated incidence/pregnancies* | 1/20 preeclampsia 1/1000 HELLP | 1/7000-1/20 000 | 1/200 000 | 1/25 000 | 3/1000 |

| Elevated blood pressure | +++ | ++ (50% of cases) | + | + | - |

| Neurologic abnormalities | +/++ (headache) | + | +++ (change in mental status, headaches, weakness) | + | – |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | 50-100 | 50-100 | <30 | <100 | <100 |

| Red blood cell fragmentation | + | + | +/+++ | +/++ | + |

| Renal impairment | –/+ | ++/+++ | –/+ | +++ | – |

| AST/ALT elevation | –/+ | +++ | – | – | – |

| Elevated PT coagulopathy | – | +++ | – | – | +/– |

| ADAMTS13 | >20% | >20% | <10% | >20% | >20% |

| Other comments | – | Elevated ammonia, low blood glucose | – | – | Biochemical evidence of DIC more common than overt DIC in pregnancy |

| . | Preeclampsia with severe features/HELLP . | AFLP . | TTP . | cm-TMA . | DIC . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated incidence/pregnancies* | 1/20 preeclampsia 1/1000 HELLP | 1/7000-1/20 000 | 1/200 000 | 1/25 000 | 3/1000 |

| Elevated blood pressure | +++ | ++ (50% of cases) | + | + | - |

| Neurologic abnormalities | +/++ (headache) | + | +++ (change in mental status, headaches, weakness) | + | – |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | 50-100 | 50-100 | <30 | <100 | <100 |

| Red blood cell fragmentation | + | + | +/+++ | +/++ | + |

| Renal impairment | –/+ | ++/+++ | –/+ | +++ | – |

| AST/ALT elevation | –/+ | +++ | – | – | – |

| Elevated PT coagulopathy | – | +++ | – | – | +/– |

| ADAMTS13 | >20% | >20% | <10% | >20% | >20% |

| Other comments | – | Elevated ammonia, low blood glucose | – | – | Biochemical evidence of DIC more common than overt DIC in pregnancy |

Table adapted from Cines and Levine.3 Thrombocytopenia in pregnancy. Blood. 2017;130(21) with permission from Elsevier.

Estimated incidence as reported in Scully.10

+, relative prevalence; −, not usually present; AFLP, acute fatty liver of pregnancy; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; PT, prothrombin time.

Diagnosis of pregnancy-specific TMA

PEC with severe features/HELLP is by far the most common cause of a TMA in the late second/third trimesters.10 The pathogenesis of PEC is incompletely understood, but it is hypothesized that abnormal placental angiogenesis contributes to the disorder.11 PEC is defined by new-onset hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg) and proteinuria (although not required if other features of organ impairment are present).8 A platelet count <100 × 109/L is a criterion for PEC with severe features (as is other organ impairment such as renal dysfunction or elevated liver function tests).8 While there is no definitive test to predict PEC, one potential biomarker is the soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1/placental growth factor ratio. A prospective analysis of over 1000 women showed that a soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1/placental growth factor ratio of ≤38 had a 99.3% negative predictive value for short-term development of PEC among women in their 37th week or less of pregnancy.12 Some centers have adopted this as a tool in predicting early PEC, but further prospective studies are needed to determine their widespread clinical utility.8 Other pregnancy-related TMAs to consider are acute fatty liver of pregnancy (a very rare cause of a TMA with profound liver dysfunction).6 Disseminated intravascular coagulation is not specific to pregnancy but is mentioned here as it is often triggered by obstetric complications (eg, acute peripartum hemorrhage, amniotic fluid embolism, or retained products of conception).13,14

Diagnosis of TTP and cm-TMA presenting during pregnancy

Pregnancy is a clear trigger for both cm-TMA and TTP. Thus, while these are rare disorders, it is not uncommon for their first presentation to occur during pregnancy or postpartum. TTP results from an acquired deficiency in ADAMTS13 in the case of immune TTP (iTTP) or an inherited deficiency (congenital TTP [cTTP]), leading to uncleaved von Willebrand multimers binding platelets and causing arterial and venous thrombosis.9 Unlike in the nonpregnant adult population, in whom iTTP is far more common, the frequency of cTTP presenting as a first episode in pregnancy is nearly equal to iTTP.15 Features that should prompt consideration of TTP as the etiology of a TMA include presentation prior to 20 weeks, severe neurologic symptoms, or cardiac injury.16 TTP should be easy to discern from other TMAs due to its supportive laboratory diagnostics (ADAMTS13 < 10%). In practice, however, the turnaround time for the ADAMTS13 assay (a send-out test at most institutions) is several days, adding complexity to the diagnosis. When TTP is suspected, treatment with plasma exchange should not be delayed while awaiting confirmatory ADAMTS13 testing given high mortality without prompt treatment.16 Once the diagnosis is confirmed by ADAMTS13 < 10%, ADAMTS13 antibody testing should be performed. Patients with cTTP will lack a detectable antibody. However, not all patients with iTTP will have detectable inhibitors if they have low-titer or nonneutralizing antibodies. The lack of ADAMTS13 recovery in remission and undetectable antibody should prompt ADAMTS13 sequencing to further confirm the diagnosis of cTTP.17

cm-TMA (formerly known as atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome) is associated with inherited genetic mutations in complement or autoantibodies that result in overactivation of the complement pathway.18 Severe acute kidney injury (stage 3 by RIFLE [Risk of renal dysfunction, Injury to the kidney, Failure of kidney function, Loss of kidney function, and End-stage kidney disease] or AKIN [Acute Kidney Injury Network] criteria) should raise high suspicion for this disorder.16 Kidney injury requiring dialysis is not a typical feature of PEC or TTP and is in fact a rare occurrence in pregnancy (a recent study reported only 188 cases in nearly 2 million pregnancies).16,19 Hematologists should also consider this diagnosis when patients present with new-onset or worsening TMA postpartum.16

CLINICAL CASE 1 (Continued)

A diagnosis of TTP is considered, and ADAMTS13 testing is sent. A multidisciplinary discussion with hematology and obstetric teams believes the presentation is most consistent with PEC with severe features based on onset in the third trimester, hypertension, and degree of acute kidney injury. Urgent induction of labor is recommended. Three days following delivery, the platelet count remains 80 × 109/L, and the patient becomes anuric with a creatinine of 3.0 mg/dL. Hepatic function and prothrombin time are normal. ADAMTS13 returns at 40%. Given the lack of clinical resolution after delivery and severe renal injury, cm-TMA is suspected. The team initiates eculizumab with rapid improvement in her platelet count followed by renal recovery over the next few weeks.

Management of pregnancy-specific TMA

Once the diagnosis is established, the management of pregnancy-related TMA is driven by the obstetrics team. With PEC with severe features/HELLP, delivery is recommended at or beyond 34 weeks, and expectant management before 34 weeks is only appropriate when strict selection criteria are applied and with close monitoring of maternal and neonatal status.8

Management of TTP or cm-TMA

As case 1 highlights, the diagnosis of TTP or cm-TMA can be difficult to distinguish from the more common PEC with severe features/HELLP in the late second/third trimester. However, efforts should be made to attempt to identify cases of TTP and cm-TMA as delivery is not typically required for these disorders, nor is it definitive management. For a detailed review of the management of TTP and cm-TMA, we refer readers to a recent American Society of Hematology education review by Scully.10 Briefly, TTP and cm-TMA are managed similarly in pregnancy as they would be in the general population.20 Key caveats for the management of iTTP during pregnancy are as follows: (1) caplacizumab does not have sufficient safety data to be routinely recommended for use, and (2) a more nuanced risk/benefit analysis of rituximab is needed due to neonatal risks.20,21 cTTP can be managed with fresh-frozen plasma infusions alone instead of plasma exchange if the diagnosis is known. For cm-TMA, the C5 complement inhibitor, eculizumab, has safety data to support its use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.10,22 Both cm-TMA and TTP can be associated with good maternal and fetal outcomes when promptly diagnosed and managed, even in early pregnancy, and thus do not necessitate urgent delivery when responding to therapy.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 30-year-old woman with chronic ITP treated with eltrombopag desires to conceive. Before starting eltrombopag, she had multiple ITP relapses with platelets <10 × 109/L without major bleeding, which responded to steroids. Her platelets have remained in the 100 to 200 × 109/L range since starting eltrombopag 2 years ago. After discussion with her hematologist, she decides to discontinue eltrombopag while trying to conceive. Two months later, she becomes pregnant. Her platelet count remains above 30 × 109/L during early pregnancy, and thus she remains off medications. She notes petechiae when she is 28 weeks pregnant and is found to have a platelet count of 5 × 109/L.

Preconception counseling for patients with chronic ITP

ITP is caused by autoantibodies to platelets that accelerate their clearance.23 Pregnancy is not contraindicated in a patient with chronic ITP but would ideally be delayed in the setting of recent major bleeding, refractory severe thrombocytopenia, and/or thrombocytopenia requiring teratogenic medications.3 Like the general population, patients with ITP can also develop gestational thrombocytopenia (or other pregnancy-specific causes of thrombocytopenia), resulting in lower platelet counts than their typical baseline. Reese et al1 reported that in pregnant patients with a preexisting diagnosis of ITP, platelet counts of less than 80 × 109/L occurred in over 50% (13 of 24). A retrospective analysis of data from a tertiary care center found approximately one-third of patients with known ITP require treatment during pregnancy.24 Additionally, they reported 42% of patients with preexisting ITP before pregnancy responded to first-line therapies when they required treatment during pregnancy.24 Prenatal counseling in a patient with ITP should include discussion of what therapies may be required during pregnancy. For some patients, the desire for a future pregnancy may play a role in choosing their long-term management strategy for chronic ITP, as many of the medications for chronic ITP have limited data in pregnancy (outlined below).25 Splenectomy as a treatment modality for chronic ITP offers the best chance of a durable response (occurs in ~50%-70% of patients) and may limit the need for medications during pregnancy, although this cannot be guaranteed.25,26

Management of ITP during pregnancy

Most patients who can maintain a platelet count ≥30 × 109/L during pregnancy do not require treatment until near delivery. Table 3 outlines therapies for ITP and considerations for pregnancy. First-line treatment is generally corticosteroids, but recommended starting dose varies, with some clinicians trialing lower doses (10-20 mg prednisone daily) if thrombocytopenia is not severe and delivery is not imminent.2 Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) also has good safety data in pregnancy and can be used when a more rapid platelet count rise is needed, such as prior to delivery. A retrospective review of 149 patients with ITP during pregnancy found similar responses with corticosteroids vs IVIG (38% vs 39%, P = .71).27 Notably, response to both of these first-line therapies was lower than those typically reported in nonpregnant women. Still, ITP refractory to steroids/IVIG requiring second-line therapies is a rare entity in pregnancy, although incidence is not well defined.

Therapies for immune thrombocytopenia and considerations in pregnancy

| . | Dosing . | Pregnancy-specific notes . |

|---|---|---|

| First line | ||

| Prednisone | 0.25-1 mg/kg* | Maternal—increased risk for gestational diabetes, mood lability Fetal—increased risk of cleft palate in early pregnancy |

| IVIG | 0.5-2 g/kg IV in divided dosing over 1-5 days (maximum 1 g/kg/24 hours) | Maternal—thrombotic risk in general population studies, hemolysis Fetal—hemolysis |

| Second line† | ||

| Splenectomy | NA | Maternal—safety reported up to the second trimester; impaired future immune response to encapsulated organisms, requires vaccinations to decrease risk |

| Azathioprine | 1-2 mg/kg PO once per day (maximum 150 mg/d) | Maternal—reports of use in rheumatologic/transplant indications in pregnancy |

| Cyclosporine | 5-6 mg/kg/d PO divided into 2 doses (titrate to blood levels of 100-200 ng/mL) | Maternal—reports of use in rheumatologic/transplant indications in pregnancy |

| Rituximab | 375 mg/m2 IV once per week × 4 weeks | Maternal—increased susceptibility to viral infections, reactivation of hepatitis B infection Fetal—risk to neonate of B-cell lymphopenia |

| TPO-R agonists‡ Romiplostim Eltrombopag | 1-10 µg/kg subq weekly 25-75 mg PO daily | Maternal/fetal—data limited to mostly retrospective data/case series |

| Rho(D) immune globulin | HgB ≥10 g/dL: 50 µg as a single injection or separate days HgB 8 to <10 g/dL: 25 to 40 µg as a single injection or can be given as 2 divided doses on separate days HgB <8 g/dL: use not recommended | Maternal—risk of severe intravascular hemolysis Fetal—possible hemolysis |

| . | Dosing . | Pregnancy-specific notes . |

|---|---|---|

| First line | ||

| Prednisone | 0.25-1 mg/kg* | Maternal—increased risk for gestational diabetes, mood lability Fetal—increased risk of cleft palate in early pregnancy |

| IVIG | 0.5-2 g/kg IV in divided dosing over 1-5 days (maximum 1 g/kg/24 hours) | Maternal—thrombotic risk in general population studies, hemolysis Fetal—hemolysis |

| Second line† | ||

| Splenectomy | NA | Maternal—safety reported up to the second trimester; impaired future immune response to encapsulated organisms, requires vaccinations to decrease risk |

| Azathioprine | 1-2 mg/kg PO once per day (maximum 150 mg/d) | Maternal—reports of use in rheumatologic/transplant indications in pregnancy |

| Cyclosporine | 5-6 mg/kg/d PO divided into 2 doses (titrate to blood levels of 100-200 ng/mL) | Maternal—reports of use in rheumatologic/transplant indications in pregnancy |

| Rituximab | 375 mg/m2 IV once per week × 4 weeks | Maternal—increased susceptibility to viral infections, reactivation of hepatitis B infection Fetal—risk to neonate of B-cell lymphopenia |

| TPO-R agonists‡ Romiplostim Eltrombopag | 1-10 µg/kg subq weekly 25-75 mg PO daily | Maternal/fetal—data limited to mostly retrospective data/case series |

| Rho(D) immune globulin | HgB ≥10 g/dL: 50 µg as a single injection or separate days HgB 8 to <10 g/dL: 25 to 40 µg as a single injection or can be given as 2 divided doses on separate days HgB <8 g/dL: use not recommended | Maternal—risk of severe intravascular hemolysis Fetal—possible hemolysis |

Reprinted from Blood Reviews, Pishko et al., Thrombocytopenia in pregnancy: Diagnosis and approach to management, 40: 100638. Copyright (2019), with permission from Elsevier.

Typical dosing for ITP 1 mg/kg; some experts suggest trialing lower doses in pregnancy.

Inadequate data to support an order to second-line approach.

Off-label use in pregnancy.

HgB, hemoglobin; IV, intravenous; NA, not applicable; PO, per os.

In a patient with ITP refractory without any response to first-line therapies, an alternative etiology for thrombocytopenia should be considered. This is particularly important to consider in patients who lack even a short-lived response to IVIG and without a history of ITP outside of pregnancy. In a patient with other cytopenias, a bone marrow biopsy may be considered (noting this is typically not necessary for the diagnosis of ITP).28,29 For second-line treatment of ITP in pregnancy, splenectomy has been described (although not commonly performed and may carry increased risk when performed in pregnant patients) until late in the second trimester.30,31 Rituximab has data in pregnancy but carries potential risks of neonatal B-cell depletion.32 While use of thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) in ITP management is increasingly common, to date, use of TPO-RAs in pregnancy has been limited and caution is required given they are likely to cross the placenta.33 Table 4 reviews outcomes from 1 clinical trial recombinant human TPO (rhTPO), available only in China,34 and the largest retrospective review of TPO-RA in pregnancy to date.35 Michel et al35 examined outcomes from 15 women (17 pregnancies) with preexisting ITP treated with romiplostim or eltrombopag in preparation for delivery (58%), refractory symptomatic ITP (4 pregnancies), or continuation of treatment prior to pregnancy (3). Median exposure during pregnancy to these agents was 4.4 weeks. Response to TPO-RA was seen in 77% of cases. No maternal or fetal thrombotic events were noted. Prospective studies on the use of TPO-RA in refractory ITP during pregnancy are needed, but unfortunately, at the time of this writing, clinicaltrials.gov lists no active trials other than with rhTPO (NCT05333744). Given the paucity of data, the use of the TPO-RA in pregnancy should be limited to patients with refractory disease and requires a thorough risk/benefit discussion with the patient. Another novel agent for ITP in nonpregnant individuals, fostamatinib, is associated with reported adverse effects on organogenesis in animal studies and thus should not be used during pregnancy or lactation.36

Selected studies of thrombopoietin receptor agonist use in pregnancy

| Study . | Medications . | Design . | Population . | Weeks of TPO-RA exposure during pregnancy . | Outcomes . | Adverse events . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kong et al34 | Recombinant human thrombopoetin (rhTPO) | Multicenter single-arm open-label prospective study (China) | N = 31, pregnant patients with platelet count less than 30 × 109/L despite IVIG/corticosteroids* | 2 weeks of once-daily rhTPO followed by maintenance dosing tapered to every other day when platelets exceeded 50 × 109/L and discontinued at 100 × 109/L | Response: platelet count >30 × 109/L (and at least 2 × baseline) on day 14 achieved in 74.2% (24/31) Complete response: platelet count >100 × 109/L achieved in 32% (10/31) | Maternal: Dizziness (1) Fatigue (1) Pain at injection site (1) Neonate: Thrombocytopenia (9) Abdominal distention (1) |

| Michel et al35 | Eltrombopag or romiplostim | Multicenter observational study (international) | N = 15 women, 17 pregnancies, pregnant patients with diagnosis of either primary or secondary ITP treated with TPO-RA for at least 1 week during pregnancy | Median 4.4 weeks (range, 1-39 weeks) | Response: platelet count >30 × 109/L (and at least 2 × baseline) achieved in 66% (10/15) Complete response: platelet count >100 × 109/L and absence of bleeding achieved in 40% (6/15) | Maternal: Headaches (2) Neonate: Preterm delivery (5) Thrombocytopenia (6) Death (trisomy 8) (1)† Pulmonary artery stenosis (1) Grade 1 intraventricular hemorrhage (1)† |

| Study . | Medications . | Design . | Population . | Weeks of TPO-RA exposure during pregnancy . | Outcomes . | Adverse events . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kong et al34 | Recombinant human thrombopoetin (rhTPO) | Multicenter single-arm open-label prospective study (China) | N = 31, pregnant patients with platelet count less than 30 × 109/L despite IVIG/corticosteroids* | 2 weeks of once-daily rhTPO followed by maintenance dosing tapered to every other day when platelets exceeded 50 × 109/L and discontinued at 100 × 109/L | Response: platelet count >30 × 109/L (and at least 2 × baseline) on day 14 achieved in 74.2% (24/31) Complete response: platelet count >100 × 109/L achieved in 32% (10/31) | Maternal: Dizziness (1) Fatigue (1) Pain at injection site (1) Neonate: Thrombocytopenia (9) Abdominal distention (1) |

| Michel et al35 | Eltrombopag or romiplostim | Multicenter observational study (international) | N = 15 women, 17 pregnancies, pregnant patients with diagnosis of either primary or secondary ITP treated with TPO-RA for at least 1 week during pregnancy | Median 4.4 weeks (range, 1-39 weeks) | Response: platelet count >30 × 109/L (and at least 2 × baseline) achieved in 66% (10/15) Complete response: platelet count >100 × 109/L and absence of bleeding achieved in 40% (6/15) | Maternal: Headaches (2) Neonate: Preterm delivery (5) Thrombocytopenia (6) Death (trisomy 8) (1)† Pulmonary artery stenosis (1) Grade 1 intraventricular hemorrhage (1)† |

One additional patient enrolled but found to have aplastic anemia and not included in analysis.

Events felt to be unrelated or very unlikely related to the medication.

CLINICAL CASE 2 (Continued)

The patient is started on 1 mg/kg prednisone with minimal initial improvement in her platelet count IVIG (1 g/kg) daily for 2 days is added with a transient rise to 50 × 109/L platelets but a fall to 9 × 109/L 2 weeks later. She is concerned with infectious risk of the immunosuppressants. After discussing with her hematologist again about the limited data for TPO-RAs in pregnancy, she opts for restarting eltrombopag. Two weeks after initiation of eltrombopag, her platelet count improves to 80 × 109/L. Prednisone is weaned off over the course of 1 month. At 39 weeks' gestation, she goes into spontaneous labor, and her platelet count is 90 × 109/L. She is able to receive epidural anesthesia given stable platelet counts and has an uncomplicated vaginal delivery.

Management of thrombocytopenia at time of delivery

Thrombocytopenia is particularly challenging near time of delivery due to the hemostatic challenges of childbirth and risks with epidural anesthesia. The platelet threshold necessary for epidural placement is not well studied and can vary by institution but is generally avoided at platelet counts less than 80 × 109/L.37 Platelet counts of 30 to 50 × 109/L are otherwise felt to be sufficient for vaginal delivery or cesarean section in the absence of another coagulopathy. Mode of delivery should be guided by obstetric indication.24 Tranexamic acid administered shortly after delivery can be a useful adjunct in patients with thrombocytopenia.38 As for neonatal outcomes with maternal ITP, studies report 10% to 15% of neonates are born with a platelet count less than 150 × 109/L39 Severe bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage, appears rare in the neonate, and its presence should raise concern for an alternate etiology, such as neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia.6,40

Conclusions

Determining the etiology of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary approach between hematology and the obstetrics team, particularly to distinguish cm-TMA/TTP from the more common hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. In patients with refractory ITP, further prospective studies evaluating TPO-RA use in pregnancy are needed.

Acknowledgments

Allyson M. Pishko is supported by a 2019 Hemostasis and Thrombosis Mentored Research Award supported by Sanofi Genzyme. Figures and visual abstract made with biorender.com.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Allyson M. Pishko has received research funding on behalf of her institution from an educational grant from Sanofi Genzyme.

Ariela L. Marshall: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Thrombopoietin-receptor agonists in pregnancy is discussed.