Abstract

Mast cell disorders include mastocytosis and mast cell activation syndromes. Mastocytosis is a rare clonal disorder of the mast cell, driven by KIT D816V mutation in most cases. Mastocytosis is diagnosed and classified according to World Health Organization criteria. Mast cell activation syndromes encompass a diverse group of disorders and may have clonal or nonclonal etiologies. Hematologists may be consulted to assist in the diagnostic workup and/or management of mast cell disorders. A consult to the hematologist for mast cell disorders may provoke anxiety due to the rare nature of these diseases and the management of nonhematologic mast cell activation symptoms. This article presents recommendations on how to approach the diagnosis and management of patients referred for common clinical scenarios.

Learning Objectives

Review the diagnostic criteria and classification of mastocytosis

Identify which patients with mast cell activation symptoms and elevated tryptase levels need further workup for a mast cell disorder

CLINICAL CASE

A 35-year-old man is referred for evaluation of a mast cell disorder. He was admitted to the hospital for hypotensive syncope after sustaining a wasp sting while biking. He felt flushed and light-headed and collapsed within 10 minutes of the sting. When emergency medical services arrived, his systolic blood pressure was noted to be 50 mmHg, with a heart rate of 120/min. There were no hives or angioedema, and the skin exam otherwise was unremarkable. His past medical history is significant for occasional flushing and lightheadedness with vigorous exercise. A serum tryptase level obtained 1 hour after the episode in the emergency department was 120 ng/mL. Another tryptase level 1 week later when he is at his baseline was 28 ng/mL.

Introduction

Consults with a hematologist for a “mast cell disorder” can provoke anxiety for a number of different reasons. First, these disorders are rare, and the provider may not have enough practical experience to direct a diagnostic workup, choose the right tests, and interpret them correctly. Second, treatment guidelines for many disease categories are evolving. Third, many patients with mast cell disorders have no abnormalities in other hematologic lineages, and therefore the hematologist may feel the treatment options to be out of their range of expertise. Likewise, there may be questions about when and how to initiate a workup for a patient referred to rule out a mast cell disorder due to symptoms of mast cell activation or elevated tryptase.

The hematologist may receive consultations or referrals for mast cell disorders due to a number of different clinical scenarios:

Patient has an established diagnosis of advanced systemic mastocytosis (advSM) and is in need of cytoreductive therapy of the mast cell disease and any associated non–mast cell neoplastic component such as a myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN).

Patient has skin lesions of maculopapular mastocytosis, and a bone marrow biopsy is needed to confirm or rule out systemic mastocytosis and categorize the disease.

Patient has a diagnosis of cutaneous or nonadvanced (indolent) systemic mastocytosis, and recommendations for management and follow-up are needed.

Patient has an elevated tryptase level.

Patient has symptoms of mast cell activation, and an opinion is needed regarding whether the patient is in need of further hematologic workup.

Before discussing each of these scenarios, a primer on the diagnosis and classification of mastocytosis and mast cell activation disorders would be helpful.

Mast cell disorders

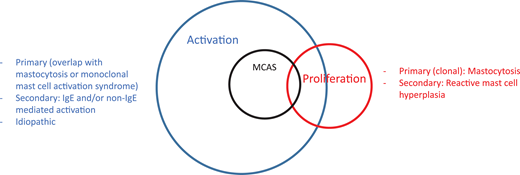

Mast cell disorders can be broadly categorized into those involving mast cell activation and those involving proliferation, with a significant overlap between the 2 categories (Figure 1).1 One can also encounter the terminology of “clonal” and “nonclonal” mast cell disorders in the literature, the former referring to mastocytosis and the latter referring to patients presenting with recurrent idiopathic anaphylaxis or other mast cell activation disorders without evidence of mastocytosis.2 The prototypical proliferative mast cell disorder is mastocytosis.3,4 Although patients with rare myelomastocytic leukemia or reactive mast cell hyperplasia present with increased mast cells in bone marrow biopsies, these are not “disorders of the mast cell” and are not discussed here.5

Mast cell disorders can be separated into those involving proliferation and activation. Mastocytosis is a clonal proliferative disorder of the mast cell and its progenitor. Reactive mast cell hyperplasia can be seen in a number of inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. Mast cell activation disorders (MCADs) include a broad range of conditions stemming from primary (mastocytosis/monoclonal MCAS), secondary (IgE and non–IgE-mediated mast cell activation due to allergic and nonallergic inflammatory and neoplastic diseases), and idiopathic origins. MCAS is a subgroup of MCADs usually presenting with severe episodic symptoms, which may be similar to anaphylaxis (see text for explanation). There may be overlap in patients with mastocytosis presenting with recurrent anaphylaxis symptoms or in patients with monoclonal MCAS.

Mast cell disorders can be separated into those involving proliferation and activation. Mastocytosis is a clonal proliferative disorder of the mast cell and its progenitor. Reactive mast cell hyperplasia can be seen in a number of inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. Mast cell activation disorders (MCADs) include a broad range of conditions stemming from primary (mastocytosis/monoclonal MCAS), secondary (IgE and non–IgE-mediated mast cell activation due to allergic and nonallergic inflammatory and neoplastic diseases), and idiopathic origins. MCAS is a subgroup of MCADs usually presenting with severe episodic symptoms, which may be similar to anaphylaxis (see text for explanation). There may be overlap in patients with mastocytosis presenting with recurrent anaphylaxis symptoms or in patients with monoclonal MCAS.

Diagnosis and classification of mastocytosis

Mastocytosis is a clonal disease of the mast cell progenitor, most often driven by a somatic gain-of-function mutation in KIT, resulting in the pathologic accumulation and activation of mast cells in tissues. It can be diagnosed in children and adults. The driver mutation is KIT D816V in more than 90% of adults and in about 30% of children.6

Pediatric-onset disease

Pediatric-onset mastocytosis usually presents in the first year of life with typical maculopapular skin lesions, also known as urticaria pigmentosa. Pediatric mastocytosis generally has a self-limited course, with spontaneous resolution or significant regression by adolescence.7 Systemic involvement can be diagnosed in about 10% of cases. These children present with progressively increasing tryptase levels, liver or spleen enlargement, lymphadenopathy, or unexplained abnormalities in the complete blood count with differential. The peripheral blood KIT D816V mutation may be positive. Children with typical self-limited pediatric mastocytosis have polymorphic skin lesions, while children with systemic disease have monomorphic, smaller lesions resembling adult- onset skin lesions. Other rare types of skin involvement in children include mastocytomas and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (CM).8 A bone marrow biopsy is usually not necessary in children with typical polymorphic skin lesions and a tryptase level within normal range unless the child presents with increasing tryptase levels or one of the red flags mentioned above, or the skin lesions fail to improve by adolescence. It is very unusual for pediatric patients with mastocytosis to present with symptoms of mast cell activation without skin lesions (as opposed to some adult patients). Therefore, in a pediatric patient referred for mast cell activation symptoms without skin lesions, a bone marrow biopsy is usually not necessary unless there is another indication. If such a patient has an elevated baseline tryptase (normal range is considered <11.5 ng/mL in most commercial assays), hereditary alpha tryptasemia (HaT) should be considered first (see below for more detailed discussion). If HaT is not found, a bone marrow biopsy can be considered.

Adult-onset disease

Adult-onset mastocytosis can be diagnosed in the third decade of life or later.9 Patients may present with maculopapular CM lesions, symptoms of mast cell activation such as recurrent anaphylaxis, signs and symptoms of a hematologic disorder, or skeletal abnormalities on imaging raising suspicion for a metastatic disease or myeloma. Adult-onset mastocytosis is almost always systemic, and a bone marrow biopsy is needed to establish the diagnosis. Systemic disease refers to the presence of neoplastic mast cells in extracutaneous tissue.

The World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria for systemic mastocytosis are shown in Table 1.10,11 A major criterion plus 1 minor criteria or 3 minor criteria are required to establish the diagnosis.

WHO diagnostic criteria for systemic mastocytosis

| Major criterion . | Comments . |

|---|---|

| Multifocal compact infiltrates of mast cells (>15 cells per infiltrate) in a tissue biopsy other than skin (such as bone marrow). | Mast cells are best visualized by tryptase or CD117 immunohistochemical stains in biopsy sections. These infiltrates are generally found in perivascular and paratrabecular locations. |

| Minor criteria | |

| Mast cells co-express CD25, CD2, and CD30. | CD25 is the most specific neoplastic mast cell marker. CD2 may be absent in some advanced SM cases. CD30 has been recently added as a marker in the latest WHO document. These markers can be assessed by serial sections by immunohistochemistry or by flow cytometry. However, mast cell flow cytometry should be treated as a rare event analysis with acquisition of ideally 1 million or more events. Typical leukemia/lymphoma FC panels do not contain enough cells to gate on mast cells. |

| Morphological abnormalities in mast cells, such as spindle-shaped, elongated mast cells with hypogranulation, cytoplasmic projection, and an off-centric or multilobated nucleus. | More than 25% of mast cells in the infiltrate should be morphologically aberrant. A bone marrow aspirate smear is the best sample to evaluate for these aberrant mast cell forms. Mast cells are usually found embedded in or in close proximity to spicules. There is insufficient data on other tissue biopsies to assess mast cell morphology. A detailed photographic guide to these abnormalities is presented in Sperr et al.42 |

| Detection of KIT D816V mutation or another gain of function KIT mutation in blood, bone marrow, or another noncutaneous tissue. | Mutation detection should be done by a high-sensitivity test such as allele specific PCR or droplet digital PCR with a sensitivity to detect mutated allele frequency of <0.1%. NGS panels or sequencing-based assays lack this sensitivity and are often falsely negative. |

| Baseline serum or plasma tryptase level of >20 ng/ml. | Tryptase is a highly specific marker for mast cell burden and activation. It should be measured when the patient is at baseline and not after an anaphylactic or mast cell activation event, during which it may be found elevated regardless of mastocytosis. This criterion is not valid if the patient has another myeloid neoplasm as tryptase can be found in smaller quantities in myeloid progenitor cells. |

| Major criterion . | Comments . |

|---|---|

| Multifocal compact infiltrates of mast cells (>15 cells per infiltrate) in a tissue biopsy other than skin (such as bone marrow). | Mast cells are best visualized by tryptase or CD117 immunohistochemical stains in biopsy sections. These infiltrates are generally found in perivascular and paratrabecular locations. |

| Minor criteria | |

| Mast cells co-express CD25, CD2, and CD30. | CD25 is the most specific neoplastic mast cell marker. CD2 may be absent in some advanced SM cases. CD30 has been recently added as a marker in the latest WHO document. These markers can be assessed by serial sections by immunohistochemistry or by flow cytometry. However, mast cell flow cytometry should be treated as a rare event analysis with acquisition of ideally 1 million or more events. Typical leukemia/lymphoma FC panels do not contain enough cells to gate on mast cells. |

| Morphological abnormalities in mast cells, such as spindle-shaped, elongated mast cells with hypogranulation, cytoplasmic projection, and an off-centric or multilobated nucleus. | More than 25% of mast cells in the infiltrate should be morphologically aberrant. A bone marrow aspirate smear is the best sample to evaluate for these aberrant mast cell forms. Mast cells are usually found embedded in or in close proximity to spicules. There is insufficient data on other tissue biopsies to assess mast cell morphology. A detailed photographic guide to these abnormalities is presented in Sperr et al.42 |

| Detection of KIT D816V mutation or another gain of function KIT mutation in blood, bone marrow, or another noncutaneous tissue. | Mutation detection should be done by a high-sensitivity test such as allele specific PCR or droplet digital PCR with a sensitivity to detect mutated allele frequency of <0.1%. NGS panels or sequencing-based assays lack this sensitivity and are often falsely negative. |

| Baseline serum or plasma tryptase level of >20 ng/ml. | Tryptase is a highly specific marker for mast cell burden and activation. It should be measured when the patient is at baseline and not after an anaphylactic or mast cell activation event, during which it may be found elevated regardless of mastocytosis. This criterion is not valid if the patient has another myeloid neoplasm as tryptase can be found in smaller quantities in myeloid progenitor cells. |

Patients fulfilling only 1 or 2 minor clonality criteria (KIT mutation and/or CD25 expression) with symptoms of mast cell activation are termed to have monoclonal mast cell activation syndrome (MMAS).11 MMAS represents a low-burden clonal mast cell disease and is managed similarly to systemic mastocytosis.

An important point has to be made about KIT D816V mutation detection: next generation sequencing (NGS) or sequencing- based mutation detection methods are often not adequate, and KIT D816V allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or digital droplet PCR are required, especially if peripheral blood is used for screening (see scenario 4 below). However, NGS would be useful for evaluating for additional mutations that one would typically see in advSM, especially hematologic non–mast cell neoplasm (SM-AHN), as these mutations may have further prognostic significance.

Bone marrow biopsy and aspirate is the gold standard to establish the diagnosis by checking for the molecular and histopathologic markers below, as the bone marrow is almost uniformly involved in SM. However, working with a gastroenterologist may often be required in the further workup of symptoms such as abdominal pain and diarrhea. In this regard, immunohistochemical stains for tryptase, CD117, and CD25 should be employed on endoscopic biopsies to determine whether abdominal symptoms may be due to mast cell infiltration or mediator release or both. Some mast cells in gastrointestinal (GI) tract biopsies may be negative for tryptase and positive for CD117. It should be noted that an increased number of mast cells alone in the GI tract are not diagnostic of mastocytosis and that bands or clusters of aberrant mast cells fulfilling WHO pathology criteria are required to prove GI involvement.12

Well-differentiated systemic mastocytosis (WDSM) is a rare histologic subtype in which mast cells have a mature, round morphology, do not express aberrant CD25 or CD2, and usually lack the typical KIT D816V mutation, making it a challenging diagnosis.13,14 Patients with WDSM can have a history of pediatric-onset cutaneous disease that may have resolved or been persistent. Mast cells in WDSM express CD30, which should not be present in normal mast cells.

Classification of mastocytosis

The most recent WHO classification of mastocytosis is shown in Table 2.

WHO classification of mastocytosis

| Category . | Comment . |

|---|---|

| Cutaneous mastocytosis | Most common category in children. Subtypes include MPCM, mastocytoma, and diffuse CM. |

| Systemic mastocytosis | Presence of neoplastic mast cell infiltrates in extracutanous tissues. Most common in adults. |

| Indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM) | The most common category of SM, representing >80% of patients with SM. Patients in this category have mast cell collections meeting WHO criteria for systemic disease in the bone marrow but do not have an associated hematologic neoplasm or advanced disease findings or 2 or more B findings of SSM. Patients with ISM have a life expectancy that is comparable to the general age-matched population with less than 5% risk of progression to advanced disease. |

| Bone marrow mastocytosis (BMM) | This category was added in the most recent WHO document and was formerly included in ISM. BMM is diagnosed in a patient without skin lesions, tryptase level <125, no mast cell infiltrates in extramedullary tissue, and otherwise fits the criteria for ISM. This category is believed to have a lower risk of progression than ISM and SSM. |

| Smoldering systemic mastocytosis (SSM) | This is a rare category of nonadvanced SM with higher mast cell burden as evidenced by 2 or more B findings: i. tryptase level ≥200 ng/mL or bone marrow biopsy infiltration by mast cells of ≥30% or KIT D816V variant allele fraction of ≥10% in bone marrow or peripheral blood; ii. splenomegaly without hypersplenism and/or hepatomegaly without liver dysfunction and/or lymphadenopathy >2 cm; iii. myeloproliferation or subtle morphologic abnormalities in myeloid cells without meeting the criteria for a WHO-classified neoplasm. Patients with SSM may have a higher rate of progression to advSM, which still remains <10%. |

| Systemic mastocytosis with associated hematologic non–mast cell neoplasm (SM-AHN) | These patients have an AHN (usually an MPN or MDS) meeting the WHO criteria in addition to SM. Prognosis is determined by the AHN but is generally poor, with a median survival time of about 2 years after diagnosis. |

| Aggressive systemic mastocytosis (ASM) | Patients with ASM have high-level mast cell burden and tissue dysfunction due to infiltrating mast cells (also known as C findings). One or more C findings attributable to MC infiltration are required for diagnosis: cytopenias (hemoglobin <10 g/dL, platelets <100 000, and neutropenia <1000), liver dysfunction with portal hypertension, elevated liver function tests, ascites, malabsorption, and diarrhea with extensive GI infiltrates, splenomegaly with hypersplenism, large (≥2 cm) lytic bone lesions with pathological bone fractures. It should be noted that osteoporosis and smaller lytic and sclerotic bone lesions are common in all categories of SM and are not considered a C finding. Patients with ASM have a reduced life expectancy, with <3 years of average survival after diagnosis. |

| Mast cell leukemia (MCL) | MCL is diagnosed when ≥10% mast cells are found in peripheral circulation or ≥20% in bone marrow aspirate smears in a nonspicular area. It should be noted that 20% infiltration grade refers to bone marrow aspirate and not to bone marrow biopsy. Patients without circulating mast cells are referred to as aleukemic MCL. Patients with typical MCL also have C findings similar to ASM and carry a very poor prognosis. A chronic form of MCL without C-findings or cytopenias have recently been recognized with more favorable survival rates. |

| Mast cell sarcoma | Rare invasive solid mast cell tumor with poor prognosis. |

| Category . | Comment . |

|---|---|

| Cutaneous mastocytosis | Most common category in children. Subtypes include MPCM, mastocytoma, and diffuse CM. |

| Systemic mastocytosis | Presence of neoplastic mast cell infiltrates in extracutanous tissues. Most common in adults. |

| Indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM) | The most common category of SM, representing >80% of patients with SM. Patients in this category have mast cell collections meeting WHO criteria for systemic disease in the bone marrow but do not have an associated hematologic neoplasm or advanced disease findings or 2 or more B findings of SSM. Patients with ISM have a life expectancy that is comparable to the general age-matched population with less than 5% risk of progression to advanced disease. |

| Bone marrow mastocytosis (BMM) | This category was added in the most recent WHO document and was formerly included in ISM. BMM is diagnosed in a patient without skin lesions, tryptase level <125, no mast cell infiltrates in extramedullary tissue, and otherwise fits the criteria for ISM. This category is believed to have a lower risk of progression than ISM and SSM. |

| Smoldering systemic mastocytosis (SSM) | This is a rare category of nonadvanced SM with higher mast cell burden as evidenced by 2 or more B findings: i. tryptase level ≥200 ng/mL or bone marrow biopsy infiltration by mast cells of ≥30% or KIT D816V variant allele fraction of ≥10% in bone marrow or peripheral blood; ii. splenomegaly without hypersplenism and/or hepatomegaly without liver dysfunction and/or lymphadenopathy >2 cm; iii. myeloproliferation or subtle morphologic abnormalities in myeloid cells without meeting the criteria for a WHO-classified neoplasm. Patients with SSM may have a higher rate of progression to advSM, which still remains <10%. |

| Systemic mastocytosis with associated hematologic non–mast cell neoplasm (SM-AHN) | These patients have an AHN (usually an MPN or MDS) meeting the WHO criteria in addition to SM. Prognosis is determined by the AHN but is generally poor, with a median survival time of about 2 years after diagnosis. |

| Aggressive systemic mastocytosis (ASM) | Patients with ASM have high-level mast cell burden and tissue dysfunction due to infiltrating mast cells (also known as C findings). One or more C findings attributable to MC infiltration are required for diagnosis: cytopenias (hemoglobin <10 g/dL, platelets <100 000, and neutropenia <1000), liver dysfunction with portal hypertension, elevated liver function tests, ascites, malabsorption, and diarrhea with extensive GI infiltrates, splenomegaly with hypersplenism, large (≥2 cm) lytic bone lesions with pathological bone fractures. It should be noted that osteoporosis and smaller lytic and sclerotic bone lesions are common in all categories of SM and are not considered a C finding. Patients with ASM have a reduced life expectancy, with <3 years of average survival after diagnosis. |

| Mast cell leukemia (MCL) | MCL is diagnosed when ≥10% mast cells are found in peripheral circulation or ≥20% in bone marrow aspirate smears in a nonspicular area. It should be noted that 20% infiltration grade refers to bone marrow aspirate and not to bone marrow biopsy. Patients without circulating mast cells are referred to as aleukemic MCL. Patients with typical MCL also have C findings similar to ASM and carry a very poor prognosis. A chronic form of MCL without C-findings or cytopenias have recently been recognized with more favorable survival rates. |

| Mast cell sarcoma | Rare invasive solid mast cell tumor with poor prognosis. |

CM is the most common category in children with involvement limited to the skin. Patients with CM most often present with polymorphic skin lesions in the first year of life. Other less common skin manifestations of CM include mastocytomas and diffuse CM. These children do not require a bone marrow biopsy unless one of the red flag signs discussed above is present. In contrast, adult patients with skin lesions almost always have bone marrow involvement. If an adult patient with skin lesions does not have a bone marrow biopsy, that patient should be classified as “mastocytosis in the skin” rather than CM, as the probability of systemic disease is high.

Systemic mastocytosis means the presence of neoplastic mast cells meeting WHO diagnostic criteria in noncutaneous tissue, characteristically bone marrow. Systemic mastocytosis can be further subdivided into nonadvanced SM (bone marrow mastocytosis [BMM], indolent SM [ISM], and smoldering SM [SSM]) and advanced SM (SM-AHN, aggressive SM [ASM], and mast cell leukemia [MCL]) based on histopathologic criteria, end organ dysfunction, and the presence of another associated non–mast cell clonal disease).11 Patients with advanced SM usually have other myeloid mutations detected in NGS, in addition to KIT D816V.15

As mentioned in Table 2, osteoporosis or sclerotic lesions should not be misinterpreted as advanced disease as they are common findings in ISM. To that end, a routine dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry bone density scan is recommended for each patient diagnosed with SM. Furthermore, radiographic imaging of areas with bone pain may be considered in individual patients. A bone scan may show increased uptake focally or appear as a superscan, although it is not routinely recommended. We would recommend treatment of osteoporosis in collaboration with an endocrinologist. Bisphosphonates or denosumab has been successfully used in these patients.16

Mast cell sarcoma is an exceedingly rare subtype that does not meet the diagnostic criteria for SM but is characterized by a high-grade invasive solid MC tumor that carries a poor prognosis.17

Categories of systemic mastocytosis include ISM (most common), BMM, SSM, SM-AHN, ASM, and MCL. See Table 2 for important comments about these categories.

Mast cell activation syndromes

Mast cell activation syndromes (MCASs) represent a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by (1) the episodic presence of mast cell activation symptoms in more than 2 organ systems, such as cutaneous, cardiovascular, GI, pulmonary, and naso-ocular; (2) response of symptoms to mast cell mediator–targeting drugs; and (3) the detection of a validated marker of mast cell activation during the symptomatic phase.2,18 The best validated surrogate marker of mast cell activation is tryptase.19 Tryptase should be checked at baseline and within 4 hours of a suspected mast cell activation event. A formula of 20% of baseline plus 2 ng/mL is used to calculate the minimal increase required to diagnose mast cell activation.20 Urinary metabolites of other mast cell mediators such as histamine, prostaglandin D2, and leukotriene C4 measured in a 24-hour or spot collection can also be used to document mast cell activation if tryptase levels are not available; however, the sensitivity and specificity of these markers as well as the minimal increases and cutoff levels diagnostic for mast cell activation have not been established.21 A patient with recurrent anaphylaxis is a prototypical presentation of MCAS; however, less severe manifestations can meet the above criteria.

MCAS can be primary or clonal when it is associated with mastocytosis or MMAS, secondary when associated with immunoglobulin (Ig) E or non–IgE-mediated mast cell activation triggers, or idiopathic when no underlying cause has been found.

There is quite an extensive controversy surrounding the diagnosis of MCAS, and alternative diagnostic schemes with broader inclusion criteria may result in diagnosing nearly 17% of the general population with MCAS.22 However, this can become problematic for patients whose symptoms may be caused by another entity that may simply be associated with reactive mast cell activation because focusing on mast cell activation may leave the underlying entity undiagnosed. Contributing to this controversy somewhat is the International Classification of Diseases ICD-10-CM classification of diagnostic codes that currently includes additional categories of mast cell activation, including “Mast cell activation, not otherwise specified,” which until recently did not have diagnostic guidance.23 A detailed discussion of mast cell activation disorders is outside the scope of this article, as hematologists are generally not expected to diagnose and treat these disorders.

With this background information in mind, let us examine specific consultation scenarios mentioned at the beginning of the text.

1. Patients with advSM. This group of patients represents a classical indication for referral to a hematologist. Patients with advanced SM are in need of cytoreductive therapy and treatment of non–mast cell hematologic neoplasias such as MPNs and MDSs.4,24 The recent approval of KIT D816V–targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) revolutionized the treatment of patients with advSM, who typically have a reduced life expectancy.25-27 Since most of these patients present with mutations in addition to KIT D816V, additional therapies in those who do not respond or lose their response to TKIs may be needed, and targeted or palliative treatment options for the associated AHN regardless of mastocytosis should be considered. These options are discussed in a separate article by Gotlib in this educational program.43

2. The patient has skin lesions of maculopapular mastocytosis, and a bone marrow biopsy is needed to confirm or rule out systemic mastocytosis and categorize the disease. This is another common scenario for referral to the hematologist. The approach in this scenario is fairly straightforward. If the patient is an adult with skin lesions, the likelihood of systemic disease is high, and a bone marrow biopsy and aspiration is indicated to establish the diagnosis and categorize the disease. In pediatric patients presenting with typical CM, a bone marrow biopsy is generally not indicated due to the low risk of systemic disease unless the child has liver or spleen enlargement, has unexplained persistent or progressive lymphadenopathy, has peripheral blood abnormalities not explainable by another process, demonstrates consistently increasing tryptase levels in repeated measurements, has a positive peripheral blood KIT D816V mutation, or has persistent or progressive skin disease after adolescence.

3. The patient has a diagnosis of cutaneous or nonadvanced (indolent) systemic mastocytosis, and recommendations for management and follow-up are needed. In this scenario, patients do not have a hematologic abnormality but present for management of various mast cell activation symptoms, such as flushing, abdominal pain, diarrhea, peptic symptoms, tachycardia, hypotensive recurrent anaphylaxis, neurocognitive problems such as brain fog, musculoskeletal pain, and fatigue. Symptoms vary greatly from patient to patient; while some have minimal or no symptoms, others may have severe and disabling presentations. Symptom burden does not correlate with the extent of bone marrow infiltration by mast cells. Up to 50% of adult patients may experience anaphylaxis during the course of their disease.28 A prescription of multiple doses of self-injectable epinephrine is therefore recommended for all patients diagnosed with SM. Approximately 1 of 3 patients have clinically significant osteoporosis,16 and about 10% may have an associated IgE-mediated hymenoptera (bee or vespid) venom allergy, which can be life threatening.29 In this scenario, hematologists may feel they lack the experience or expertise to manage these symptoms, and it is reasonable to refer these patients to an allergist with special expertise in treating mast cell activation symptoms.

Common management strategies include the avoidance of triggers known to cause symptoms for each specific patient and the use of anti–mast cell mediator–targeting therapies such as H1 and H2 antihistamines, antileukotriene drugs, and mast cell stabilizers such as cromolyn.30,31 The anti-IgE monoclonal antibody omalizumab has been shown to reduce recurrent anaphylactic symptoms in patients who do not respond to first-line antimediator therapies.32

Patients with SM may be more susceptible to perioperative MC activation events and anaphylaxis, although most patients undergo successful surgeries with premedication and the selection of agents less likely to cause mast cell activation and the avoidance of those known to cause symptoms in individual patients.33 Multidisciplinary management involving surgeons, allergists, and anesthesiologists is crucial to mitigate MC activation in patients needing surgery. Pregnancy is generally well tolerated in SM, and the management of SM in pregnancy is discussed elsewhere.34

KIT D816V–targeting TKIs are currently approved for the treatment of advanced SM and are in the clinical trial stage for patients with nonadvanced SM who do not respond to optimized antimediator management.35 Hematological expertise may be required for the treatment and monitoring of these patients with TKIs in the future if they are approved for nonadvanced SM indications. Avapritinib, currently approved for advSM, was evaluated in a multicenter placebo-controlled clinical trial. According to part 1 data available from the PIONEER study (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT03731260), a dose of 25 mg/d was selected to move forward in an expanded part 2 cohort based on safety and efficacy data showing an approximately 30% reduction in patient-reported symptom scores and no serious adverse events.36 Avapritinib has also been shown to be highly effective in improving skin lesions in SM, and these improvements were associated with objective reductions in mast cell disease burden. The PIONEER trial is currently closed to new patient enrollment. Other clinical trials currently open for enrollment to evaluate D816V-selective KIT inhibitors in patients with ISM involve BLU-263 (HARBOR, NCT04910685) and bezuclastinib (SUMMIT, NCT05186753).

4. The patient has an elevated tryptase level. In this scenario a patient with or without mast cell activation symptoms and no skin lesions is referred due to an elevated tryptase level to rule out mastocytosis. The most common cause of an elevated tryptase level in the general population is HaT, which is seen in up to 7% of the population in the US (Figure 2).37 HaT is an autosomal dominantly transmitted genetic polymorphism of uncertain clinical significance due to copy number variations of the TPSAB1 gene encoding the alpha tryptase gene. Alpha tryptase, a proenzyme with no proteolytic activity, accounts for the bulk of measurable serum tryptase in baseline conditions. A median normal tryptase level is around 4.5 to 5 ng/mL. Patients with HaT are generally measured to have tryptase levels higher than 8 ng/mL. The elevation in tryptase level is proportionate to the number of alpha-encoding TPSAB1 genes. Due to the autosomal-dominant mode of transmission, patients with HaT are expected to have at least 1 parent with an elevated tryptase level and have a 50% chance of passing it on to their children. The initial description of HaT associated this genetic event with a number of seemingly unrelated phenotypic features, such as irritable bowel syndrome, skeletal abnormalities, retained primary dentition, skin rashes, and venom allergies.37 Subsequent studies, however, failed to consistently confirm many of the nonallergic phenotypes.38 HaT alone is not a mast cell activation disorder; however, some reports indicate that HaT may be a disease-modifying factor in those with concurrent hymenoptera venom allergy, idiopathic anaphylaxis and mastocytosis accounting for more severe mast cell activation symptoms in HaT carriers, although prospective studies with no referral bias are needed to confirm these associations.39 Interestingly, HaT is 2 to 3 times more prevalent in patients with systemic mastocytosis than in the general population.37 Patients with SM and concurrent HaT tend to present more often with mast cell activation symptoms rather than skin lesions or hematologic abnormalities.40 Whether this association is due to a mechanistic link between HaT and SM or selection bias needs to be investigated in future studies. There is no specific treatment available (or needed) for HaT, other than the treatment of underlying mastocytosis symptoms or management of anaphylaxis.

Testing for HaT (TPSAB1 gene copy number) is currently commercially available in the US. In this test, copy numbers of alpha and beta alleles are reported, and their sum should be 4 in most individuals. Possible combinations include 4 beta and 0 alpha, 3 beta and 1 alpha, and 2 beta and 2 alpha. A quick interpretation would be to consider any number above 4 to be an extra alpha allele, provided there are at least 2 alpha alleles. For example, in a patient with 3 beta and 2 alpha alleles, there is 1 extra alpha allele. However, as stated above, a positive test for HaT does not rule out concurrent mastocytosis. Patients with HaT and mastocytosis tend to have higher tryptase levels than what might be expected for HaT alone. A correction of tryptase level according to HaT genotype has been proposed as tryptase level divided by the extra alpha allele number plus 1. For example, if the serum tryptase is 15 ng/mL and the patient has an extra copy of the alpha tryptase allele, the corrected tryptase level would be 7.5 ng/mL.

Our approach to a patient with an elevated tryptase level higher than 8 ng/mL without skin lesions of mastocytosis or any other reason to explain elevated tryptase (such as myeloid neoplasia, chronic renal failure, etc) is as follows: If the patient has a history of severe hypotensive anaphylaxis and a score of 2 points or greater in REMA score (see below),41 or if the corrected tryptase is greater than 8 ng/mL, we consider a bone marrow biopsy and aspiration to rule out mastocytosis. Some experts also propose a high-sensitivity peripheral blood KIT D816V test in patients reluctant to have a bone marrow biopsy; however, a negative result in this test would not necessarily rule out mastocytosis. If the patient, however, is asymptomatic or has nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, abdominal pain, or multiple food intolerances, HaT testing is done. If this test shows positive results and the corrected tryptase is lower than 8 ng/mL, a bone marrow biopsy is optional, and the patient can be followed yearly with symptomatic assessment and a complete blood count with differential and tryptase levels. If the patient shows an increasing trend in tryptase levels or develops new symptoms such as hypotensive anaphylaxis, a bone marrow biopsy is considered. If HaT testing is negative in a patient with an elevated tryptase level, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended regardless of symptomatic status.

The clinical case presented at the beginning of this article is an example of a patient with an elevated baseline tryptase and severe hypotensive anaphylaxis. Even though he is fairly asymptomatic other than the anaphylaxis episode, his elevated baseline tryptase and high REMA score indicate the need for a bone marrow biopsy. While one can also check HaT status, a positive HaT test does not necessarily rule out mastocytosis in this case. The patient should also be referred to an allergist for venom allergy testing and consideration for venom immunotherapy and should be prescribed self-injectable epinephrine for as-needed use.

5. The patient has symptoms of mast cell activation with a normal baseline tryptase level, and an opinion is needed regarding whether the patient is in need of further hematologic workup. This scenario is probably the most confusing for the hematologist, as most of these patients present without an obvious hematologic abnormality, and hematologists may feel they lack sufficient expertise to evaluate and treat mast cell activation or anaphylaxis. While a normal tryptase level does not necessarily rule out systemic mastocytosis, SM is exceedingly rare in patients with a baseline tryptase lower than 4 ng/mL. Further guidance can be obtained by assessing the patient for REMA criteria (Figure 3).41 These criteria were developed by the Spanish Network of Mastocytosis and have a high predictive value for determining underlying mastocytosis in patients presenting with anaphylactic symptoms. Patients with hypotensive anaphylaxis episodes (particularly after bee/wasp stings or idiopathic) without urticaria or angioedema are at particular risk. It should be noted that while patients with several unexplainable symptoms such as chronic fatigue; fibromyalgia; headaches; irritable bowel syndrome-like symptoms; dysautonomia, including postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome; Ehlers-Danlos syndrome; and multiple food, drug, and environmental intolerances are considered for a diagnosis of mast cell disorder, there are no mechanistic studies proving a causal link between a primary mast cell disorder, such as mastocytosis or MCAS, and these entities, and such patients, especially those with normal tryptase levels, are not candidates for a hematologic workup. Some of these patients may have other localized manifestations of mast cell activation common to the general population, such allergic rhinitis, urticaria, and even flushing, and these patients could be evaluated for MCAS with the help of an allergist for these specific entities. Patients with a history of anaphylaxis should be evaluated and managed by an allergist.

REMA score to predict clonal mast cell disease (mastocytosis) in patients presenting with mast cell activation symptoms and/or anaphylaxis. Reproduced with permission from Alvarez-Twose et al.41

REMA score to predict clonal mast cell disease (mastocytosis) in patients presenting with mast cell activation symptoms and/or anaphylaxis. Reproduced with permission from Alvarez-Twose et al.41

Conclusions

Mast cell disorders encompass mastocytosis and MCASs. Due to their rarity and various forms of presentation without a hematologic disease, hematologists may feel they lack sufficient expertise to diagnose and treat these disorders. However, using the approach outlined above for different scenarios, most of these patients can be triaged to an appropriate diagnostic workup. A hematopathologist with experience in reviewing bone marrow and other tissue biopsy samples as well as an allergist knowledgeable about the symptomatic management of these patients can be helpful resources during this process. A referral to a center with more expertise can be considered for management recommendations and evaluation for clinical trials. A list of these academic centers is available through the American Initiative on Mastocytosis (www.aimcd.net). Finally, the patient support group the Mast Cell Disease Society (www.tmsforacure.org) has many useful informational materials for patients diagnosed with a mast cell disorder.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Cem Akin: consultancy: Blueprint Medicines, Cogent; research funding: Blueprint Medicines, Cogent.

Off-label drug use

Cem Akin: omalizumab is discussed. In addition, avapritinib, BLU-263, and bezuclastinib are in clinical trials for ISM.