Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is classified by risk groups according to a number of genetic mutations, which may occur alone or in combination with other mutations and chromosomal abnormalities. Prognosis and appropriate therapy can vary significantly based on a patient's genetic risk group, making mutation-informed decisions crucial to successful management. However, the presence of measurable residual disease (MRD) after induction and consolidation therapy, before hematopoietic cell transplant, and during posttransplant monitoring can be even more significant to patient prognosis than their genetic subtype. Clinicians must select MRD-monitoring methods most appropriate for a patient's genetic profile and a treatment regimen that considers both a patient's primary genetic subgroup and other risk factors, including MRD information. Recent clinical trial data and drug approvals, together with advances in the validation of MRD using next-generation sequencing, require a deeper understanding of the complex AML mutation and MRD matrix, enabling more insightful monitoring and treatment decisions for intensively treated AML patients. Here, we provide an overview on methods and clinical consequences of MRD monitoring in genetic subgroups of patients with AML. As treatment options become more personalized, on-treatment MRD monitoring will become even more important to effective AML care.

Learning Objectives

Select the appropriate MRD technology in the context of the ELN risk groups for intensively treated AML patients

Apply the prognostic implications of mutations and MRD to the risk groups and treatment phases of transplant-eligible AML patients

Compare the treatment options in MRD-positive and MRD-negative patients depending on genetic risk and treatment phase

Introduction

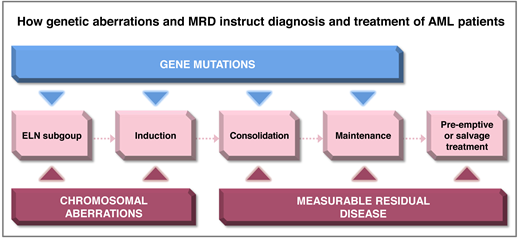

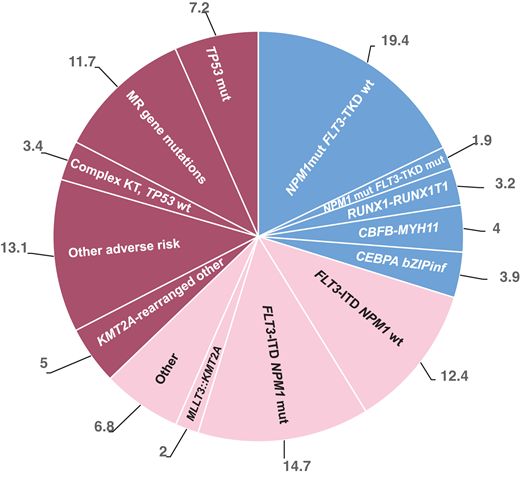

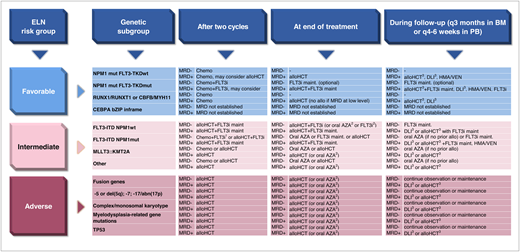

Molecular and cytogenetic aberrations are major determinants of prognosis in patients treated with intensive induction and consolidation treatment for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Measurable residual disease (MRD) monitoring is increasingly being used to refine risk assessment during treatment and detect relapse early during follow-up. The European LeukemiaNet (ELN) 2022 classification assigns a large number of genetic subgroups into 3 risk categories (Figure 1). Due to the heterogeneity of AML, several MRD technologies are required to monitor response and relapse in all patients. The recommended technologies for each ELN subgroup are shown in Figure 2. The rates of remission and MRD negativity vary by treatment regimen and genetic subgroup, although these rates are often not reported in detail for the current ELN risk groups (Table 1; Figure 3). Genetic subgroups, different treatment options, and various MRD methods provide a complex matrix of dependencies that clinicians should consider to guide patients through their disease journey (Figure 4). We will exemplify such dependencies with 2 patient scenarios.

Frequency of molecular and therapeutic subgroups based on the ELN 2022 classification modified from Rausch et al,2who reported frequencies of ELN 2022 subgroups from an intensively treated AML cohort (n = 1118) with a median age of 58 years (range, 18-86 years).2 mut, mutated; wt, wild type.

Recommended MRD technology by ELN risk and genetic subgroup for pre-alloHCT and post-alloHCT MRD monitoring. bZIP inframe, inframe mutations in the bZIP domain; mut, mutated; wt, wild type.

Recommended MRD technology by ELN risk and genetic subgroup for pre-alloHCT and post-alloHCT MRD monitoring. bZIP inframe, inframe mutations in the bZIP domain; mut, mutated; wt, wild type.

Rates of CR and CRi (A) and rates of MRD negativity (B) reported in clinical trials are shown by genetic subgroup or MRD technology. The cited clinical trials are listed in Table 1. Data on mutated NPM1 and CBF MRD are based on qPCR assessment. Data on FLT3-ITD are based on NGS. MFC-MRD assessment includes studies of intermediate-risk AML with or without FLT3-ITD or mutated NPM1. CBF, core-binding factor; mut, mutated.

Rates of CR and CRi (A) and rates of MRD negativity (B) reported in clinical trials are shown by genetic subgroup or MRD technology. The cited clinical trials are listed in Table 1. Data on mutated NPM1 and CBF MRD are based on qPCR assessment. Data on FLT3-ITD are based on NGS. MFC-MRD assessment includes studies of intermediate-risk AML with or without FLT3-ITD or mutated NPM1. CBF, core-binding factor; mut, mutated.

Therapeutic consequences of MRD after 2 cycles of treatment, at the end of treatment, and during follow-up for the genetic subgroups defined by ELN. abn, abnormality; AZA, azacitidine; BM, bone marrow; bZIP inframe, inframe mutations in the bZIP domain; chemo, consolidation chemotherapy; del, deletion; HMA, hypomethylating agent; maint, maintenance; MRD−, MRD negative; MRD+, MRD positive; mut, mutated; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain; wt, wild type. 1Chemotherapy consolidation plus FLT3i may be considered in patients with low FLT3-ITD allelic ratio with NPM1 comutation. 2If alloHCT is contraindicated. 3With or without salvage treatment prior to alloHCT/DLI.

Therapeutic consequences of MRD after 2 cycles of treatment, at the end of treatment, and during follow-up for the genetic subgroups defined by ELN. abn, abnormality; AZA, azacitidine; BM, bone marrow; bZIP inframe, inframe mutations in the bZIP domain; chemo, consolidation chemotherapy; del, deletion; HMA, hypomethylating agent; maint, maintenance; MRD−, MRD negative; MRD+, MRD positive; mut, mutated; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain; wt, wild type. 1Chemotherapy consolidation plus FLT3i may be considered in patients with low FLT3-ITD allelic ratio with NPM1 comutation. 2If alloHCT is contraindicated. 3With or without salvage treatment prior to alloHCT/DLI.

Results of published studies reporting remission and MRD status after intensive induction and consolidation chemotherapy

| References . | ELN subgroup . | MRD method . | Patient population N . | Rate of CR/CRi . | Rate of MRD negativity in CR/CRi patients . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnett et al47 | Favorable NPM1 | No MRD | 1113 | 85% | - |

| Döhner et al48 Schwoerer et al49 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR/dPCR | 588 | 86% | 56% |

| Lambert et al50 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 278 | 89.6 | 37% after induction 1; 93% at EOT |

| Krönke et al51 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 245 | 91% | 19% after induction; 45% after EOT (CR) |

| Lambert et al52 | Favorable NPM1 | - | 271 | 87.1% | - |

| Dillon et al53 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 1206 | 82% | 54% (of 107 NPM1 mut. pts) (CR) |

| Balsat et al54 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 229 | 97% | 55% |

| Othman et al55 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 737 | Only CR pts included | 81% (CR) |

| Bataller et al56 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 110 | 91% | 58% (CR) |

| Dillon et al6 | Favorable NPM1 | NGS | 822 | Only CR pts prior to alloHCT included | 84.7% (CR) |

| Bouvier et al57 | Favorable cytogenetics | - | 238 | 91.6% | - |

| Yin et al58 | Favorable CBF | qPCR/dPCR | 278; 163 (t(8;21)) 115 (inv(16)) | t(8;21): 97% inv(16): 92% (CR) | t(8;21): 47% inv(16): 51% (CR) |

| Rücker et al59 | Favorable CBF t(8;21) | qPCR | 155 | 98% | PB 74% EOT; PB 48% after 2 cycles (CR) |

| Borthakur et al60 | Favorable CBF | qPCR | 45 | 95% | 98% |

| Willekens et al61 | Favorable CBF t(8;21) | qPCR | 94 | Only CR pts included | 70% (in PB) at EOT; during FU PB-MRD negativity 81.9% (CR) |

| Krauter et al62 | Favorable CBF | qPCR | 37 | Only CR pts included | 70.3% MRD level <1% (CR) |

| Weisser et al63 | Favorable CBF t(8;21) | qPCR | 45 | 95.5% | Data on below and above median AML1-ETO expression; no cutoff defined |

| Corbacioglu et al64 | Favorable CBF (inv16) | qPCR | 53 | Only CR pts included | 59% (CR) |

| Deotare et al65 | Favorable CBF | qPCR | 80 | 90% | 33% |

| Puckrin et al66 | Favorable CBF | qPCR | 114 | 99.1% (CR) | 72.8% (CR) |

| Marcucci et al67 | Favorable CBF | - | 61 | 90% (CR) | - |

| Paschka et al68 | Favorable CBF | - | 89 | 94% | - |

| Freeman et al69 | NPM1 | MFC | GO1: 100 GO2: 115 | 80% 77% | 62% 70% |

| Freeman et al70 | Favorable (FLT3-ITD wt, NPM1 mut) | MFC | 213 | 88% | 53% |

| Stone et al9 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | - | 717 | 59% (CR) | - |

| Röllig et al71 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | - | 267 | 60% (CR) | - |

| Erba et al8 Levis et al72 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | NGS FLT3-ITD | 539 | 71.6% | 24.6% |

| Grob et al4 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | NGS FLT3-ITD; MFC (in 138 of 161 pts with FLT3-ITD) | 161 | Only CR pts included | 71% (CR) |

| Loo et al5 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | NGS | 104 | Only CR pts included | 63.5% (CR) |

| Dillon et al6 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | NGS | 822 | Only CR pts included | 86% (CR) |

| Han et al73 | Intermediate risk | MFC/LAIP | 235 | 91.5% | 56.6% after cycle 3 |

| Freeman et al74 | Intermediate risk | MFC | 1754 279 with C2 MRD | 65.5% (CR) | 64% (CR) |

| Tettero et al75 | Intermediate risk | MFC; qPCR for NPM1 | 153 | Only CR/CRi patients included | 72% |

| Venditti et al76 | Intermediate risk | MFC; qPCR for CBF and NPM1 | 500 | 72% (CR) | 45% negative by both techniques (CR) |

| Freeman et al69 | FLT3-ITD | MFC | GO1: 80 GO2: 99 | 71% 72% | 59% 58% |

| Freeman et al70 | Intermediate | MFC | 1230 | 68% | 41% |

| Lancet et al77 | Adverse | MFC | 309 | 47.7% | - |

| Rautenberg et al78 | tAML, AML-MRC | MFC | 188 | 47% | 64% |

| Freeman et al70 | MRC | MFC | 246 | 46% | 24% |

| Freeman et al69 | TP53 | MFC | GO1: 32 GO2: 37 | 47% 43% | 22% 23% |

| References . | ELN subgroup . | MRD method . | Patient population N . | Rate of CR/CRi . | Rate of MRD negativity in CR/CRi patients . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnett et al47 | Favorable NPM1 | No MRD | 1113 | 85% | - |

| Döhner et al48 Schwoerer et al49 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR/dPCR | 588 | 86% | 56% |

| Lambert et al50 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 278 | 89.6 | 37% after induction 1; 93% at EOT |

| Krönke et al51 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 245 | 91% | 19% after induction; 45% after EOT (CR) |

| Lambert et al52 | Favorable NPM1 | - | 271 | 87.1% | - |

| Dillon et al53 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 1206 | 82% | 54% (of 107 NPM1 mut. pts) (CR) |

| Balsat et al54 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 229 | 97% | 55% |

| Othman et al55 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 737 | Only CR pts included | 81% (CR) |

| Bataller et al56 | Favorable NPM1 | qPCR | 110 | 91% | 58% (CR) |

| Dillon et al6 | Favorable NPM1 | NGS | 822 | Only CR pts prior to alloHCT included | 84.7% (CR) |

| Bouvier et al57 | Favorable cytogenetics | - | 238 | 91.6% | - |

| Yin et al58 | Favorable CBF | qPCR/dPCR | 278; 163 (t(8;21)) 115 (inv(16)) | t(8;21): 97% inv(16): 92% (CR) | t(8;21): 47% inv(16): 51% (CR) |

| Rücker et al59 | Favorable CBF t(8;21) | qPCR | 155 | 98% | PB 74% EOT; PB 48% after 2 cycles (CR) |

| Borthakur et al60 | Favorable CBF | qPCR | 45 | 95% | 98% |

| Willekens et al61 | Favorable CBF t(8;21) | qPCR | 94 | Only CR pts included | 70% (in PB) at EOT; during FU PB-MRD negativity 81.9% (CR) |

| Krauter et al62 | Favorable CBF | qPCR | 37 | Only CR pts included | 70.3% MRD level <1% (CR) |

| Weisser et al63 | Favorable CBF t(8;21) | qPCR | 45 | 95.5% | Data on below and above median AML1-ETO expression; no cutoff defined |

| Corbacioglu et al64 | Favorable CBF (inv16) | qPCR | 53 | Only CR pts included | 59% (CR) |

| Deotare et al65 | Favorable CBF | qPCR | 80 | 90% | 33% |

| Puckrin et al66 | Favorable CBF | qPCR | 114 | 99.1% (CR) | 72.8% (CR) |

| Marcucci et al67 | Favorable CBF | - | 61 | 90% (CR) | - |

| Paschka et al68 | Favorable CBF | - | 89 | 94% | - |

| Freeman et al69 | NPM1 | MFC | GO1: 100 GO2: 115 | 80% 77% | 62% 70% |

| Freeman et al70 | Favorable (FLT3-ITD wt, NPM1 mut) | MFC | 213 | 88% | 53% |

| Stone et al9 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | - | 717 | 59% (CR) | - |

| Röllig et al71 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | - | 267 | 60% (CR) | - |

| Erba et al8 Levis et al72 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | NGS FLT3-ITD | 539 | 71.6% | 24.6% |

| Grob et al4 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | NGS FLT3-ITD; MFC (in 138 of 161 pts with FLT3-ITD) | 161 | Only CR pts included | 71% (CR) |

| Loo et al5 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | NGS | 104 | Only CR pts included | 63.5% (CR) |

| Dillon et al6 | Intermediate FLT3-ITD | NGS | 822 | Only CR pts included | 86% (CR) |

| Han et al73 | Intermediate risk | MFC/LAIP | 235 | 91.5% | 56.6% after cycle 3 |

| Freeman et al74 | Intermediate risk | MFC | 1754 279 with C2 MRD | 65.5% (CR) | 64% (CR) |

| Tettero et al75 | Intermediate risk | MFC; qPCR for NPM1 | 153 | Only CR/CRi patients included | 72% |

| Venditti et al76 | Intermediate risk | MFC; qPCR for CBF and NPM1 | 500 | 72% (CR) | 45% negative by both techniques (CR) |

| Freeman et al69 | FLT3-ITD | MFC | GO1: 80 GO2: 99 | 71% 72% | 59% 58% |

| Freeman et al70 | Intermediate | MFC | 1230 | 68% | 41% |

| Lancet et al77 | Adverse | MFC | 309 | 47.7% | - |

| Rautenberg et al78 | tAML, AML-MRC | MFC | 188 | 47% | 64% |

| Freeman et al70 | MRC | MFC | 246 | 46% | 24% |

| Freeman et al69 | TP53 | MFC | GO1: 32 GO2: 37 | 47% 43% | 22% 23% |

CBF, core binding factor; dPCR, digital PCR; EOT, end of treatment; FU, follow-up; GO, gemtuzumab ozogamicin; inv, inversion, PB, peripheral blood; pts, patients; t, translocation; tAML, therapy-related AML (acute myeloid leukemia).

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 53-year-old woman with normal cytogenetics, an FLT3-ITD (internal tandem duplication) mutation, and concurrent IDH2 mutation (R140Q), NPM1 wild type, was diagnosed with AML, not otherwise specified, according to the International Consensus Classification (ICC). She achieved complete remission (CR) after the first induction with 7 days of cytarabine and 3 days of an anthracycline chemotherapy (a regimen known as 7 + 3) combined with midostaurin and continued treatment with 1 cycle of intermediate-dose cytarabine with midostaurin. Multicolor flow-cytometry (MFC)-MRD was negative before she received a myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (alloHCT) from a matched related donor. Pre-alloHCT next-generation sequencing (NGS) MRD results received after engraftment showed FLT3-ITD positivity with a variant allele frequency (VAF) of 0.09%. The patient received maintenance sorafenib from day 46 after alloHCT and stopped treatment after 1 year due to poor tolerance, at which point NGS-MRD was negative.

Approach to an FLT3-ITD–mutated AML patient without NPM1 mutation

Variable proportions of patients with FLT3-ITD–mutated AML without NPM1 mutation are reported: based on the HARMONY open-access big data platform, this group of patients composes 8.2% of the total AML population,1 while Rausch et al report a frequency of 12.4%.2 Based on HARMONY another 10.4% present with FLT3-ITD and NPM1 mutation, while Rausch et al report 14.7%. ELN 2022 assigns an intermediate risk to FLT3-ITD– mutated patients, independent of the allelic ratio and comutations.3 Patients with NPM1 mutations traditionally receive quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) monitoring of MRD, while those without NPM1 are traditionally monitored with MFC. NGS for FLT3-ITD has recently been validated for any NPM1 status.4-7 Standard induction treatment is 7 plus 3 in combination with an FLT3 inhibitor (FLT3i) for both groups.3

As of the approval of quizartinib in combination with 7 plus 3 chemotherapy, a second tyrosine kinase inhibitor became available to treat AML patients with FLT3-ITD. Quizartinib was evaluated in the phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled QuANTUM-First trial in newly diagnosed AML patients aged 18 to 75 years with FLT3-ITD mutation. After 1 or 2 cycles of induction treatment, CR and CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) were achieved in 71.6% and 64.9% of patients in the quizartinib and placebo groups, respectively; MRD was assessed using a PCR-NGS assay with a lower limit of detection of 2 × 10−6. The proportion of FLT3-ITD NGS-MRD low/negative patients (VAF <0.01%) was 24.6% and 21.4% of CR/CRi patients on quizartinib and placebo, respectively.8 At a median follow-up of 39.2 months, however, median overall survival (OS) was significantly longer for quizartinib (31.9 months) compared with placebo-treated patients (15.1 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.78; 95% CI, 0.62-0.98; P = .032). A subgroup analysis for OS suggested a more pronounced effect in patients younger than 60 years of age, of female sex, and with NPM1 comutation.

The efficacy of quizartinib appears comparable to midostaurin, which resulted in the same HR of 0.78 when evaluated in the RATIFY trial compared to placebo, although the analyzed population in RATIFY also included patients with FLT3-TKD (tyrosine kinase domain) mutations and restricted inclusion to patients aged 18 to 59 years.9

Secondary factors may therefore influence the decision to use midostaurin or quizartinib. For example:

Quizartinib is the only FLT3i approved for maintenance treatment after alloHCT.

The pretreatment QT interval using Fridericia's correction (QTcF) must be less than 450 ms for quizartinib and equal to or less than 500 ms for midostaurin (midostaurin dose must be reduced for QTcF of 471-500 ms).

Quizartinib is inactive against FLT3-TKD (D835) and Y842 mutations and must not be used in these patients.10

The AMLSG 16-10 trial reported a high efficacy of midostaurin in younger and older patients (61-70 years old), while the effect of quizartinib was most pronounced in patients aged less than 60 years.11

It is not understood why subgroup analyses showed a better efficacy of quizartinib in female and midostaurin in male patients.

At the time our patient was treated, quizartinib was not available. As the patient's treatment plan included alloHCT with FLT3i maintenance treatment, the patient was a woman younger than 60 years of age, and pretreatment QTcF was less than 450 ms, quizartinib would now be considered an equally effective alternative to midostaurin for this patient.

MRD monitoring of FLT3-ITD–mutated AML patients

In our patient, MRD was assessed by MFC and NGS. ELN 2021 MRD guidelines recommend monitoring patients without NPM1 mutation or fusion gene by MFC, which may be supplemented by NGS-MRD.12 Several studies have now shown the high prognostic value of FLT3-ITD as an MRD marker after 2 cycles of intensive chemotherapy, which is now considered a standard for MRD monitoring in FLT3-ITD–mutated patients when a validated NGS test is available. The prognostic effect of FLT3-ITD MRD is established for the time point after 2 cycles of chemotherapy and before alloHCT using either bone marrow or peripheral blood. The proportion of MRD-positive patients after 2 cycles of chemotherapy ranges from 29% to 56%.4,5,7,8 The most discriminatory threshold for MRD is a VAF of 0.01%, although MRD detection below this threshold is also associated with a higher relapse rate. When NGS-MRD is used, no additional prognostic value has been found for MFC-MRD.4

How can MRD results be used for guiding further treatment? Our patient had an indication for alloHCT and had achieved remission; therefore, this patient should be transplanted as soon as possible, independent of the MRD result. AlloHCT has been shown to convert 73% of MRD-positive patients to MRD negativity, and converting patients had an improved OS compared to nonconverting patients, thus providing evidence that alloHCT is an effective MRD conversion treatment.13 The use of FLT3i for MRD conversion has also been reported, with a conversion rate from positive to negative of 56% and 24% in patients without and with prior FLT3i treatment, respectively.14 However, these patients had an MRD relapse when treatment was initiated, in contrast to patients with persisting MRD after induction chemotherapy, and therefore the results cannot be simply extrapolated. In patients with FLT3-ITD and mutated NPM1 with molecular relapse, treatment with low-intensity chemotherapy and venetoclax (VEN) induced MRD negativity in 50% of patients with favorable survival rates.15 In patients with persisting MRD after 2 cycles of chemotherapy, we favor direct alloHCT without additional treatments, while in patients with an MRD relapse during follow-up, we prefer MRD converting/remission-inducing treatment before alloHCT.

Another option when intervening in MRD-positive patients is the choice of the pre-alloHCT conditioning regimen. Myeloablative conditioning is recommended for MRD-positive patients whenever possible,6,7,12 and melphalan-containing regimens have been associated with improved outcome in these patients.6,7

Maintenance treatment of FLT3-ITD–mutated AML patients

FLT3i maintenance treatment after alloHCT is recommended in all FLT3-mutated patients.3 MRD positivity before or after alloHCT is a critical indicator of a high risk of relapse. The BMT-CTN 1506 (MORPHO) trial randomized patients with FLT3-mutated AML to gilteritinib maintenance or placebo after alloHCT. The trial missed its primary end point of relapse-free survival (HR, 0.679; 95% CI, 0.459-1.005; P = .0518), but maintenance treatment significantly improved OS in the 50.5% of patients with detectable MRD before or after alloHCT.16

Similarly, quizartinib maintenance after alloHCT was associated with improved OS mainly in the subgroup of patients with composite CR and detectable MRD before alloHCT.17 In contrast to these studies, sorafenib maintenance was associated with improved leukemia-free survival and OS independent of MRD.18,19 Although all patients with FLT3-ITD should receive FLT3i maintenance after alloHCT, MRD can underscore its importance in situations in which posttransplant complications impede prompt treatment with an FLT3i. In our patient, the MRD level was positive before alloHCT, and therefore FLT3i maintenance treatment post transplant was particularly important.

FLT3i maintenance after alloHCT should be started as soon as possible after recovery of blood counts. The tested duration of maintenance treatment was between 5 to 24 months for sorafenib,18,19 36 months for quizartinib,8 and 24 months for gilteritinib.16 Whether the duration of FLT3i treatment can be guided by MRD assessment has not been studied yet and is currently not recommended. Our patient suffered from nausea and muscle aches, and upon confirmation of MRD negativity, the FLT3i was stopped. Longitudinal MRD monitoring after alloHCT may further help to guide preemptive donor lymphocyte infusions (DLIs) or reduce immunosuppression.

In summary, FLT3-ITD–mutated patients without NPM1 comutation constitute a significant number of AML patients, can now be monitored by NGS using the FLT3 mutation as an MRD marker, benefit most from post-alloHCT maintenance therapy if they are MRD positive before or after alloHCT, and have an additional treatment option with quizartinib, which also extends to maintenance treatment.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 65-year-old man was diagnosed with AML with normal cytogenetics, after which sequencing revealed a mutation in SRSF2 with a VAF of 47% and in STAG2 with a VAF of 36%. The diagnosis was revised to AML with myelodysplasia-related (MR) gene mutations without diagnostic classifiers according to ICC,20 and an adverse risk was assigned according to the ELN 2022 recommendation. He achieved CR after first induction with 7 plus 3 chemotherapy and continued treatment with 1 cycle of intermediate-dose cytarabine and reduced-intensity conditioning, followed by alloHCT from a matched unrelated donor. MFC-MRD was negative before alloHCT, while SRSF2 and STAG2 mutations were still detectable (VAF, 19% and 4%, respectively) pretransplant but became undetectable by NGS-MRD by 3 months post alloHCT. At 9 months after alloHCT, SRSF2 was detectable by NGS-MRD in bone marrow at VAF 0.05%, while STAG2 remained undetectable. A reanalysis from bone marrow after 4 weeks confirmed SRSF2 MRD at VAF 0.06%. In the absence of chronic graft-versus-host disease, DLIs were initiated, and SRSF2 MRD became undetectable during subsequent assessments.

Classification and prognosis of patients with AML with MR gene mutations

The ICC and World Health Organization classifications from 2022 introduced a diagnostic subgroup of patients with MR gene mutations based on the presence of at least 1 mutation in the genes ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, ZRSR2, and, according to ICC, RUNX1.20,21 With 11% to 24% of all patients, this subgroup represents one of the largest subgroups of AML (Figure 1).2,22-24 A frequency of up to 45% has been reported in patients older than 60 years.22 MR gene mutations are also found in 72% of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/AML.25 In two-thirds of these patients, MR gene mutations are accompanied by unfavorable cytogenetic aberrations, and 23%, 6%, and 17% carry a comutation in FLT3 (ITD, 15%; tyrosine kinase domain, 8%), IDH1, or IDH2, respectively.22

The ELN 2022 classification assigns an adverse risk to most AML patients with MR gene mutations. The adverse risk has been confirmed in several studies but questioned by others.26-30 A worse prognosis has been described for patients with 2 or more MR gene mutations compared to 1 or none.22,31 In addition, clonal dominance represented by a VAF greater than or equal to 45% has been associated with a worse prognosis compared to subclonal MR gene mutations, which may explain some of the variability of reported prognostic associations.32

According to the hierarchical classification of ICC and ELN, however, patients with NPM1 or TP53 comutation are not classified in the MR gene mutation subgroup, and co-occurring MR cytogenetic abnormalities do not change the assignment to this diagnostic category. For example, NPM1-mutated patients with MR gene mutations remain in the ELN favorable-risk group. Recent studies support this classification, showing a similar prognosis for patients with mutated NPM1 with or without MR gene mutations.33 A diagnostic difficulty arises from the co-occurrence of MR gene mutations with FLT3-ITD mutations. While MR gene mutations represent a unique diagnostic category, FLT3-ITD mutations do not. Patients with MR gene mutations are classified to the ELN adverse-risk group, while patients with FLT3-ITD are classified to the ELN intermediate-risk group. The prognostic implications of MR gene mutations co-occurring with FLT3-ITD in the absence of NPM1 await more detailed evaluation. Until then, FLT3-ITD–mutated patients are classified to the intermediate-risk group independent of MR comutations.

MRD monitoring in patients with AML with MR gene mutations

Is MRD assessment useful to refine the prognosis of patients with MR gene mutations? The ELN 2021 recommendations recommend MFC for MRD assessment in patients without an established molecular MRD marker.12 The MRD level should be assessed in the bone marrow of intensively treated patients at diagnosis to establish a leukemia-associated immunophenotype (LAIP), after 2 cycles of chemotherapy, and at the end of treatment. The LAIP-based different from normal approach is recommended as it increases the number of patients who can be monitored.34 The recommended cutoff for MRD positivity is 0.1% or more when using MFC. However, when distinguishing between ELN intermediate- and adverse-risk groups, MFC-MRD was not prognostic in ELN adverse-risk patients.35 MFC-MRD monitoring has also been shown to have a prognostic impact at 20 to 40 days after alloHCT,13 but the prognostic relevance of long-term monitoring during follow-up is not well established. MFC-MRD monitoring in patients with MDS/AML is also prognostic, although it appears less discriminatory than in patients with AML.36

Molecular monitoring by NGS using MR gene mutations is not recommended before alloHCT. Several MR genes have been associated with clonal hematopoiesis, often leading to molecular persistence despite remission of the leukemic clone. In addition, NGS-based MRD assessment after 2 cycles of intensive chemotherapy using MR gene mutations had no prognostic impact,37 as we encountered in the case described above. In contrast, NGS-MRD monitoring has been validated for FLT3-ITD– mutated patients and may also be used in patients with FLT3-ITD and MR comutations.

In patients undergoing alloHCT, longitudinal MRD monitoring after alloHCT using the mutations known from diagnosis, including MR and clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) mutations, has shown prognostic value.38,39 It is important to note that during follow-up, MRD relapse is defined as a dynamic increase of MRD, either as conversion from negative to positive or by one log10 increase.12 Using NGS for MRD monitoring after alloHCT, approximately one-third and two-thirds of hematologic relapses can be identified 3 and 1 months before hematologic relapse, respectively, with approximately 2.3 months lead time over chimerism analysis.40 CHIP and MR gene mutations were described as useful MRD markers after alloHCT, as they were associated with a longer lead time to relapse compared to mutations in signaling genes.40 However, with the rising use of post-alloHCT NGS, we will increasingly identify donor-derived CHIP, which may be ruled out by correlation with highly sensitive/molecular chimerism analysis. In the case described above, NGS-MRD converted from negative to positive, allowing the preemptive administration of DLIs, which converted the patient back to MRD-negative status.

Treatment of patients with AML with MR gene mutations

The treatment of patients with MR gene mutations is heterogeneous, depending on the co-occurring aberrations. In the absence of FLT3 mutations and World Health Organization 2016–defined MR changes (known as MRC status or MRC-AML) and a history of prior treatment with cytotoxic agents for an independent malignancy, the standard treatment is 7 plus 3 in eligible patients. In patients with MRC-AML or therapy-related AML, CPX-351 (cytarabine and daunorubicin in a 5:1 drug ratio) is considered the standard treatment.41 If FLT3 mutations are present, patients should be treated with 7 plus 3 plus an FLT3i (midostaurin or quizartinib). Most importantly, all eligible patients should undergo alloHCT, as retrospective studies showed a strong survival benefit with alloHCT in patients with AML with MR gene mutations.22,28

Maintenance treatment may include oral azacitidine in patients not undergoing alloHCT,42 an FLT3i after alloHCT in FLT3- comutated patients, or no maintenance after alloHCT in all other patients. MRD monitoring after alloHCT may guide the tapering of immunosuppression and the use of preemptive DLIs or salvage treatment of MRD relapse.43

Earlier studies showed that cladribine or fludarabine in combination with cytarabine and anthracycline improved the outcome of patients with adverse-risk cytogenetics. The United Kingdom's National Cancer Research Institute AML19 study therefore compared a combination of fludarabine, high-dose cytosine arabinoside, idarubicin, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor with CPX-351 in 189 patients with adverse karyotype AML or high-risk MDS aged 18 to 70 years.44 While the overall outcome was comparable between granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and CPX-351, an exploratory subgroup analysis showed an improved survival for CPX-351 in patients with MR gene mutations. A retrospective study suggested improved OS when venetoclax (VEN) was added to intensive chemotherapy or hypomethylating agents in patients with splicing factor mutations,45 while the prospective CAVEAT study showed a heterogeneous picture, with higher blast reductions for SRSF2-mutated cases but lower blast reductions for SF3B1- and RUNX1-mutated patients.46

Future studies will show the therapeutic value of HMA/VEN induction, the addition of VEN to 7 plus 3 or CPX-351, and the addition of IDH1/2 inhibitors to chemotherapy in patients with MR gene mutations.

In summary, patients with AML with MR gene mutations constitute a significant number of AML patients, can be monitored for MRD before alloHCT by MFC, can be monitored after alloHCT by MFC or NGS, should undergo alloHCT whenever possible, and should receive oral azacitidine as maintenance treatment if they are transplant ineligible.

Conclusion

The heterogeneity of AML in terms of molecular subgroups, treatments, and clonal evolution mandates an integrated approach to risk assessment using the genetic information at diagnosis, as well as an MRD-based response assessment during treatment. The appropriate MRD technology is determined by genetic and immunophenotypic characteristics (Figure 2). The prognostic impact of MRD in intensively treated AML patients should be considered in the context of ELN risk groups. The assessment of MRD during intensive treatment allows treatment stratification in some genetic subgroups after 2 cycles of treatment and in most subgroups at the end of treatment and during follow-up (Figure 4). This time-dependent treatment matrix evolves with every emergence of additional targeted therapies. As treatment options become more personalized in the future, on-treatment MRD monitoring will become even more important to effective AML care.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katherine Brind'Amour for editorial and Sophie Steers for graphical support.

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No. 101136502.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Michael Heuser: honoraria: Abbvie, Eurocept, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Novartis, Takeda, consultancy: Abbvie, Agios, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Glycostem, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Kura Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer, PinotBio, Roche, Tolremo; research funding: Abbvie, Agios, Astellas, Bayer Pharma AG, BergenBio, Daiichi Sankyo, Glycostem, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Loxo Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer, PinotBio, Roche.

Rabia Shahswar: travel support: Abbvie.

Off-label drug use

Michael Heuser: Gilteritinib maintenance after alloHCT is off- label; CPX-351 in AML patients with MR gene mutations is off- label; cytarabine combined with venetoclax is off-label.

Rabia Shahswar: Gilteritinib maintenance after alloHCT is off- label; CPX-351 in AML patients with MR gene mutations is off- label; cytarabine combined with venetoclax is off-label.