Abstract

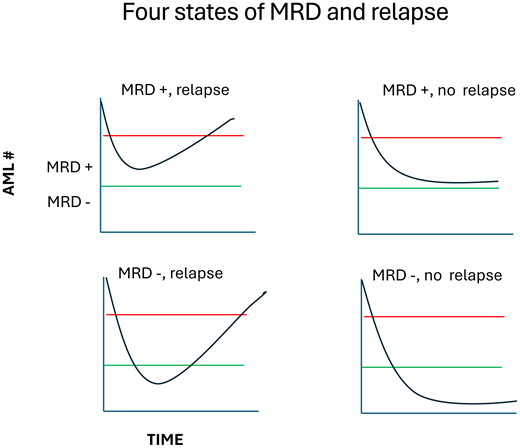

Measurable residual disease (MRD) is a strong but imprecise predictor of relapse in acute myeloid leukemia. Many patients fall into the outlier categories of MRD positivity without relapse or MRD negativity with relapse. Why? We will discuss these states in the context of “clonal ontogeny” examining how mutations, clonal structure, and Darwinian rules impact response, resistance, and relapse.

Learning Objectives

Understand the 4 states of relationship between MRD and relapse

Appreciate the complexity of mutation ontogeny and its relationship with the MRD states

CLINICAL CASE

A 45-year-old woman presents with de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML). She has a normal karyotype and mutations in genes A, B, and C. She then gets induction therapy with X and Y and has a bone marrow biopsy at day 14, which is hypoplastic. A day-30 bone marrow at count recovery shows a normal morphology and cytogenetics. Flow cytometry shows an abnormal flow phenotype of 0.2% blasts. Standard next-generation sequencing (NGS) does not show mutations.

This case is intentionally vague to highlight just a few of the issues that must be considered in the clinical context of what to think and do about measurable residual disease (MRD). Specifically, there are five main issues: (1) What is the age and history of AML? Is it de novo AML in a younger person? Is the patient older, with either known or suspected antecedent MDS? (2) What are the specific cytogenetic and gene mutations? (3) What type of therapy did the patient receive? Generic 7 + 3? Targeted therapy to a specific mutation? (4) What is the level of MRD, and when? (5) What type of assay was used, and what kind of sensitivity of detection should one expect?

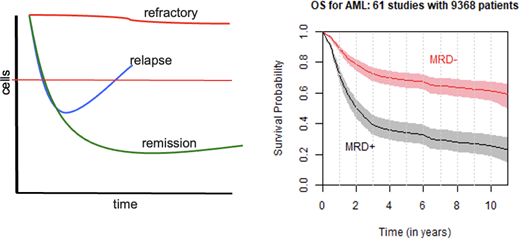

MRD is a measure of treatment response

There are several distinct outcomes of treatment for AML and other cancer types (Figure 1): resistance to therapy (“refractory,” top curve, red), remission (bottom curve, green), and relapse following initial response (middle curve, blue). Refractory and remission states may represent relatively homogeneous monoclonal or low-clonal tumors that are either insensitive or sensitive, respectively, to therapy. Relapse, however, may be the consequence of a heterogeneous, polyclonal tumor in which the selective pressure of chemotherapy eliminates sensitive cells, reducing tumor burden, but does not eliminate all tumor cells (further discussed later). Subsequently, even with continued therapy, treatment-resistant clones enjoy a competitive advantage as their treatment-sensitive counterparts are eliminated. The resulting tumor could then be populated by genetically identical progeny of these resistant cells (those resistant to the first-line therapy) or by clones that have acquired additional mutations due to the presence of chemotherapy, producing a more widely resistant tumor.

Resistance, response, and MRD. The figure on the left shows the 3 paths of cancers—refractory to therapy, relapse after response, and remission. The red horizonal line reflects clinical complete remission, thus any disease burden below the line that is detectable is MRD. On the right is the summary of a large meta-analysis of nearly 10 000 AML cases across 61 studies. While there is a large difference in outcome based on MRD status, many patients who are MRD negative relapse and die, while many with MRD do not. Why? Right panel reprinted with permission from Short et al.4

Resistance, response, and MRD. The figure on the left shows the 3 paths of cancers—refractory to therapy, relapse after response, and remission. The red horizonal line reflects clinical complete remission, thus any disease burden below the line that is detectable is MRD. On the right is the summary of a large meta-analysis of nearly 10 000 AML cases across 61 studies. While there is a large difference in outcome based on MRD status, many patients who are MRD negative relapse and die, while many with MRD do not. Why? Right panel reprinted with permission from Short et al.4

The promise of MRD

Although most AML patients treated with intensive chemotherapy can achieve complete remission (CR), the majority will relapse, and the 5-year survival is only approximately 25%.1-3 The presence of MRD among patients who have achieved CR is the most important predictor of disease recurrence and mortality.4-6 MRD assessment in AML is used to (1) provide a quantitative methodology to establish a deeper remission status; (2) refine post-remission relapse risk assessment; (3) identify impending relapse to enable early intervention; and (4) accelerate drug testing and approval as a regulatory endpoint.

MRD is often thought of as a dichotomous variable—“positive” or “negative”—but this is mostly due to limitations of the sensitivity of the assays used to detect it (flow cytometry, polymerase chain reaction [PCR], NGS) and our tendency to try to simplify rich, continuous variables into relatively dumb, yes-or-no categories. MRD is best thought of not as a thing—yes or no—but by a dynamic quantification of response, and a measure of the biology of response.

The subsequent chapters of this educational section by Drs. Heuser and DiNardo will deal with examples of how MRD can be used in specific clinical contexts, especially regarding types of therapy (low- and high-intensity chemotherapy, allogeneic transplantation). In this section we try to understand how and why the genetic landscape of AML changes with therapy, and what those changes mean in the context of what MRD is, and how to use it. By “clonal ontogeny” we refer to acquisition, evolution, and selection of genetic clones in AML. We can now track AML through therapy by multiple means—flow cytometry, PCR of specific targets, and sensitive NGS methods. This has the potential to both give us new insight into the biology of response, resistance, and relapse and allow us to use these measures to predict response, attempting abortive therapy if relapse looks inevitable. The potential uses of the study of clonal ontogeny, and methods for its study, are outlined in Box 1.

“ . . . because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know.”

Donald Rumsfeld, February 12, 2002

Why is clonal ontogeny important? How do we study it?

Clonal ontogeny is the acquisition, evolution, and selection of genetic clones. Understanding clonal ontogeny in the context of AML treatment and response follows several paths:

Clonal evolution and heterogeneity: Cancer wins by using Darwinian selection against us, as the selective pressure of treatment can create more space and resources for resistant clones to grow. Studying clonal ontogeny may help us identify and understand clonal competition and cooperation so that we can use evolutionary rules against the more virulent clones.

Tracking residual disease: By characterizing and tracking leukemic clones from diagnosis through therapy, we can predict and perhaps abort future relapse.

Targeted therapy: By using more sensitive molecular methods, we may detect persistent rare clones that might allow for specific targeted therapy.

Predicting treatment outcomes: As we improve clonal detection and characterization, it may be an early marker of novel therapeutic efficacy, greatly shortening clinical trials (see CML for an example).

Several techniques are used to study clonal ontogeny and MRD, all of which have some advantages and disadvantages.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS): Genetic panel, whole-exome, or even whole-genome sequencing are used to track genetic alterations. However, in the context of MRD, error-corrected methods must be used to gain sufficient sensitivity.

Single-cell genomics: This allows deconvolution of bulk leukemia populations, getting better insight on clonal composition and dynamics. The method also can be used to detect lineage-specific mutations and expression. Throughput and cost are major limitations.

Targeted gene molecular monitoring: Quantitative PCR or digital PCR can be used to monitor specific genetic alterations. These methods have the best combination of sensitivity and cost but have the limitation of the number of targets one can pursue in a multiplex format.

At first read (or even second read) the above seems a tad ridiculous, yet it is explanatory of many geopolitical events. However, it turns out to be an effective way to frame many problems, including MRD. There are three fundamental “known knowns” concerning MRD in AML.

MRD after chemotherapy is bad. A recent large meta-analysis is shown in Figure 1.4 MRD status was highly associated with OS and disease-free survival and stayed significant across all age groups, AML subtypes, time of MRD assessment, specimen source, and type of assays, be they flow cytometry, PCR, or NGS. Of note, MRD status assessed by cytogenetics and FISH were not associated with outcomes. Although not all studies reported the sensitivity of their analyses, those that did identified the MRD level cutoff defining negativity/positivity as 0.1%.

MRD at the time of allogeneic transplant is bad. Many studies have established that the presence of MRD prior to transplant is associated with a high risk of relapse.7-12 This holds true for both patients treated with full ablative conditioning regimens and reduced intensity regimens. Not surprising, pre-BMT MRD was somewhat worse in the nonablative setting, though interestingly enough, the specific gene mutations associated with relapse were somewhat different between the 2 conditioning settings.9

MRD after transplant is bad. Both the persistence of MRD after transplant and the emergence of MRD post-transplant from a pre-MRD negative state are associated with a high risk of relapse.8

There are many “known unknowns” of MRD in AML. Some are noted in Box 2, with accompanying (and perhaps helpful) editorial comment.

Some “known unknowns” in MRD assessment and interpretation

What is the best method(s) for MRD assessment? In many centers flow cytometry is the default measure of MRD. It has the advantages of speed and of giving an output of a single number that is easy to process and compare with previous values. Most labs have a limit of detection (LOD) of approximately 0.1%. PCR-based assays tend to be the most sensitive assays, and digital PCR assays appear dependable at the LOD. The limitations are that they are best with single targets (translocations, NPM1, FLT3). Standard NGS is acceptable for diagnostic testing, but the LOD of many platforms (1%-5%) makes it unsuitable for MRD. However, many labs use error-corrected methods that increase the sensitivity of the assay by several orders of magnitude. However, the promise of cheaper and cheaper sequencing has largely been just that (a promise).

How should MRD be measured, qualitative or quantitative? In the vast majority of MRD studies, a cutoff level is established (say, 0.1%) and patients are classified as “MRD positive” or “MRD negative” based on that arbitrary bar. There is obvious convenience in this classification, though it turns a rich, continuous variable across 5 orders of magnitude into a dumb dichotomous value. This convention ignores the effect of kinetics. For example, going from a blast percentage of 100% to >0.2% would be an MRD positive state, while going from 10% to >0.09% is MRD negative. It would seem the former would be more desirable. Also, this categorization inevitably leads to misclassification, and trials might be more efficient using actual MRD quantification values as the comparator statistic.

What is the effect of treatment on the implications of MRD? In general, the implication of MRD is unfavorable in all treatment settings, though as noted above in the transplant setting, therapy intensity may interact with the specific genetic context. This will likely become especially true as targeted therapy becomes more prevalent (eg, FLT3- or IDH-directed therapy), and the future may look more like CML, where the molecular response of the target (BCR::ABL1) drives treatment decisions. The topic of chemotherapy intensity and MRD is discussed extensively in subsequent chapters.

What is the effect of mutations—individually and in combination? As we understand the complexity of clonal structure, how to define clinically relevant MRD will necessarily become more complicated. Different mutations may have different clinically relevant thresholds. Different combinations of mutations may reflect different biology of response/resistance. For any 2 mutations existing in the same clone, the order of acquisition may influence the biology. Keep applying for those grants.

What is the biology/effect of the “cancer ecosystem”? We are only beginning to understand the role of immunology in controlling/combating emergent disease and “mopping up” resistant disease. It is likely that immunotherapy will play a major role in MRD management soon.

How will single-cell genetics be used in MRD? Single-cell work has a rich potential for understanding clonal structure, the biology of individual and complex genetics, and treatment resistance. Its role in tying MRD to outcome prediction is unclear, and yet no study has systematically compared MRD methods such as bulk flow cytometry, genotyping, and single-cell analysis.

What is the relevance/importance of CHIP? The meaning of CHIP is complicated in those that evolve to AML, even after therapeutic response, as CHIP subclones in an AML patient may be biologically different from CHIP subclones that linger without transformation in many of us. As sequencing methods become more and more sensitive, it is likely we will find low-level clones containing many other mutations than just the DTA variety. This will be challenging in the context of allogeneic transplant, as presumably some of the same CHIP mutations found in ultra-low levels in the donor will also be genes sometimes mutated in the patient's leukemia. How will one sort out at day 21 whether the same mutation is donor or host residual leukemia?

Despite the strong association of MRD and outcome (particularly relapse), Figure 1 points to a major insight where the study of clinical ontogeny becomes important. First, roughly one-third of MRD-positive patients will not relapse. Second, roughly one-third of MRD-negative cases will relapse. Why do all MRD-positive cases not relapse? Why do MRD-negative cases ever relapse? Can the careful study of response at the molecular level help us understand this and potentially improve the predictive and prognostic power of MRD?

Which mutations matter?

The year 2022 was a busy year for (re)classification systems of AML, as the European LeukemiaNet, International Consensus Classification, and World Health Organization made changes based on the increasing knowledge base of mutations and outcomes.1-3 The major changes define distinct entities of TP53-mutant AML and MDS/AML with mutations ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and/or ZRSR2. The latter group containing MDS-related mutations is common, consisting of nearly a quarter of all AML cases and nearly half of adult cases diagnosed at age >60.13 (Tables containing European LeukemiaNet classifications are in the last chapter of this education section.)

How do these genes interplay with our clinical account of AML? In the past AML has been roughly grouped in cases arising from without any hematological antecedent issue (de novo), those arising from an antecedent disorder (MDS), or those arising after genotoxic therapy (treatment related). An elegant study put the idea of genetic ontogeny on the map.14 By studying a very carefully curated set of secondary AML cases, researchers found 8 genes to be highly enriched in the s-AML population (SRSF2, SF3B1, U2AF1, ZRSR2, ASXL1, EZH2, BCOR, and STAG2) compared with de novo AML. In a subset of cases with paired MDS and subsequent AML, the subsequent mutations found in the s-AML tended to be like those found in de novo AML, especially genes involved in signal transduction pathways (eg, FLT3, RAS) and transcription factors. In addition, paired diagnosis and remission samples from secondary AML cases commonly demonstrated clonal remission, where the persistent clones retained the “early” secondary mutation type. These suggest an evolution from early leukemia events (TP53, secondary-type mutations, DMT3A, TET2, etc) with subsequent acquisition of mutations involved in further growth promotion of subclones (RAS, FLT3, transcription factor fusions, etc). The implication on MRD is 2-fold. First, in known cases of secondary AML, persistence of secondary-like mutations after induction remission is common. This is not surprising, and similarly cytogenetic lesions persist after induction therapy in transformed MDS.

How can we use this information to our best clinical practice? Interpretation requires consideration of complicating factors: first, germline mutations that may predispose to myeloid malignancies (eg, CEBPA, GATA2, JAK2, NPM1),15 and second, the presence of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminant potential (CHIP). The mutational patterns of CHIP-related mutations versus additional transforming mutations are complex and depend on several factors, including specific hematological malignancy (eg, ALL vs AML) and age (with increasing mutational load as age increases).16 Several articles suggest that prediction is improved by exclusion of mutations in DMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 (“DTA” mutations) since they are commonly found in CHIP.17-19 However, some caution is useful, since once a patient evolves into a frank leukemia, the concept of CHIP subclones as being of indeterminant prognosis is somewhat undermined. Further refinement has suggested that predictive models also eliminating splicing factor mutations and IDH2 status may improve prognostic performance (though obviously IDH2 mutation status would be imperative in therapy using an IDH2 inhibitor!).20 The clearance of non-CHIP-associated genes has been associated with better survival10,18,21,22 and conversely, their persistence associated with poor outcome.

One of the more difficult issues with MRD is how to interpret new mutations that arise during therapy but were not present at diagnosis. Two recent articles using newer, more sensitive technical approaches address the issue. In 1 study, 30 patients had both whole-exome and sensitive error-corrected panel sequencing performed.22 After standard induction therapy, a surprising 80% had persistent molecular disease. Nearly all patients with DTA mutations had persistent molecular disease of these markers—not entirely surprising. But definitely surprising, a new mutation not present at diagnosis was detected after induction therapy in nearly two-thirds of patients. A second study used ultra-sensitive duplex sequencing to study 62 patients receiving standard induction therapy.18 These cases were specifically selected to have both achieved a morphologic CR and had concurrent flow cytometry assessment of MRD. In 9 cases, new mutations were detected in CR that were not present even using a methodology with several logs more sensitivity than standard NGS. The question thus remains whether these new mutations represent de novo acquisition (perhaps following genotoxic chemotherapy) or clones present at diagnosis but so rare that even our best methodology could not detect them. In this study, however,18 the detection of new mutations had the same deleterious effect on relapse rates as did mutations that persisted with therapy.

The effect of treatment

In the most extreme cases, the effect of treatment on MRD utility can be found in allogeneic transplant, where more intense regimens directly affect the AML population and are backed by the powerful allograft immunological effect. (The influence of specific treatments for MRD given mutations and patients' physiological condition are explored in subsequent chapters and will not be repeated here.) As noted, various groups have shown that the presence of MRD before and after transplant is highly associated with inferior outcomes compared with those without MRD in those settings. Using both pre- and post-MRD status (based on flow cytometry) allowed the categorization of 4 groups, with the highest-risk group (pre- and post-MRD positive) having relapse rates of over 80% and the lowest-risk group (pre- and post-MRD negative) having a relapse risk of only 20%. However, when assessing the data for the ability to predict outcome in the individual patient, MRD-containing models were only modest in predicting outcome (C statistic of 0.7, where 0.5 is a coin flip).23

Perhaps MRD based on genetic sequencing might be better at predicting outcome. A series of studies have suggested that MRD based on gene mutation panel is associated with subsequent relapse, with the risk being higher for MRD-positive cases of transplant with reduced-intensity therapy compared with ablative regimens.9 DTA genes at transplant were not associated with a higher risk of relapse. These studies have also suggested that mutation testing pre-transplant for limited genes (NPM1, FLT3) again shows a high risk of relapse compared with those cases without MRD of these genes. Satisfying was the demonstration of a “dose response” of FLT3-ITD variant allele frequency with relapse, as such a dose response has been curiously hard to demonstrate in studies of MRD using flow cytometry.12 Lastly, a recent study of post-allograft relapses (thus, no comparator group of nonrelapsed cases) suggested relapse kinetics after transplant were influenced by the “functional class” of mutations and their stability during molecular progression.7 Mutations in epigenetic modifier and spliceosome genes had a higher prevalence of MRD positivity, greater stability before relapse (mutation present at diagnosis and at relapse), and a slower tempo from first detection to relapse, while mutations in signaling genes (eg, FLT3-ITD) demonstrated less stability (eg, not detectable at diagnosis but detectable at relapse) and a shorter time to relapse. These differences in mutation-dependent kinetics mirror those found in patients with AML after receiving chemotherapy.21,22 Approximately 80% of all MRD mutations found at relapse were present at diagnosis. Thus, a future potential application could be a cheaper, faster, targeted-approach strategy for mutation testing post-transplant, focusing only on mutations present at the time of transplant (especially if coupled with flow cytometry as another way to detect MRD). Both DTA and non-DTA mutations displayed similar relapse kinetics during the follow-up period after allogeneic transplant.

MRD, mutations, and treatment responses

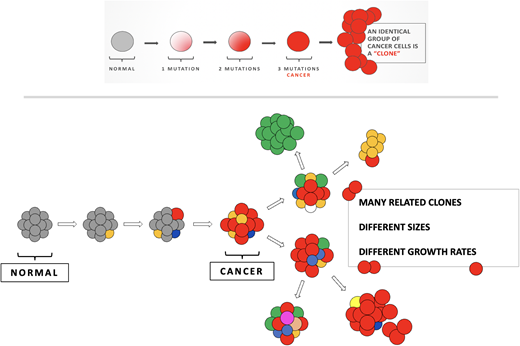

Early models of carcinogenesis suggested a linear acquisition of mutations—first “pre-leukemic” mutations that set the foundation for other mutations, leading to decreased apoptosis, differentiation, and proliferation. In the context of MRD, the potential complexity of the clonal landscape was obscured by focusing on single-gene studies (eg, FLT3-ITDs) and flow cytometry, where the reporting of a blast number does not necessarily speak to the underlying genetic complexity of those blasts. NGS studies of diagnostic and remission samples suggested a more complex picture, with a branching evolution structure24-28 (Figure 2). In this context, AML is part of the cancer ecosystem, composed of competing and cooperating populations of AML, predation (therapy and the immune system), and a landscape with shelter and food (the microenvironment). The relative size of these populations (clones), and how they change with the selective pressure of therapy, drives the initial response (MRD status), composition of the MRD, and thus relapse or cure. Thus, there is a setting of clonal complexity allowing for clones to compete and cooperate with each other (Figure 3). Under selection pressure, sensitive clones are eliminated, but resistant clones can emerge. These often emerge with new cytogenetic lesions and a different mutation landscape. These mutations can be the new acquisition of mutations, particularly in those involved in epigenetic pathways, and loss of mutations (eg, NPM1, FLT3-ITD). Recently, it has been shown in paired samples that patients with a stable genotype from diagnosis to relapse undergo epigenetic changes and bend toward convergent evolution to a common epigenetic landscape.28

Linear versus branched evolution. In linear evolution, a clone evolves by accumulating sequential biologically relevant mutations. This would be assumed to create a large cancer clone of a similar phenotype—either resistant or sensitive, depending on a patient's luck. It is harder to understand in this model why patients would respond and then relapse, unless treatment was not given long (or hard enough) to a sensitive tumor. Below shows branching evolution, with related clones that may have similar or dissimilar biological properties. This is the foundation of a Darwinian landscape where clones compete, cooperate, and are differentially selected by therapy.

Linear versus branched evolution. In linear evolution, a clone evolves by accumulating sequential biologically relevant mutations. This would be assumed to create a large cancer clone of a similar phenotype—either resistant or sensitive, depending on a patient's luck. It is harder to understand in this model why patients would respond and then relapse, unless treatment was not given long (or hard enough) to a sensitive tumor. Below shows branching evolution, with related clones that may have similar or dissimilar biological properties. This is the foundation of a Darwinian landscape where clones compete, cooperate, and are differentially selected by therapy.

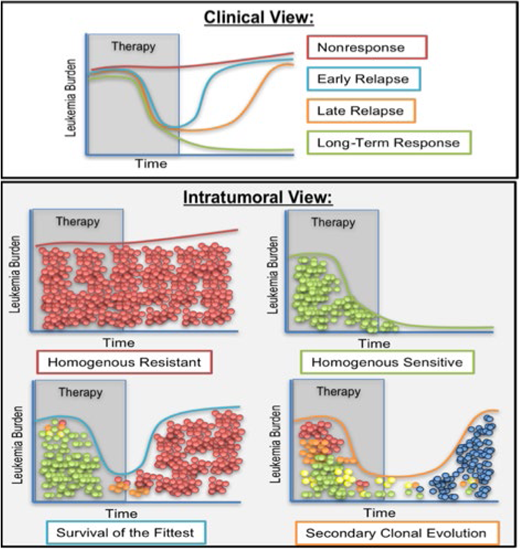

Clonal dynamics and therapeutic response. While we can see 4 general types of response to therapy in the clinic (top panel, nonresponse, early relapse, late relapse, and long-term response), the hypothesized underlying intratumoral views (bottom panel) of these scenarios could have significant implications for therapy. If the response of patients to therapeutic intervention is either a long-term response or complete nonresponse, we hypothesize that the underlying genetic diversity is minimal, with clones either homogenously sensitive or homogenously resistant to therapy. Those that initially respond to therapy but relapse early or late after therapy is completed could be examples of either selection for the fittest existing clone (early relapsers, survival of the fittest) or the emergence of new clones generated during (or by) therapy that over time cause another outgrowth of the tumor (late relapsers, secondary clonal evolution). To distinguish which of the evolutionary pressures (resistance, sensitivity, survival of the fittest, or secondary clonal evolution) apply to each clinical manifestation requires additional tools suitable for clinical monitoring of clonal diversity and clonal identities. (Figure by Dr. Amy Paguirigan).

Clonal dynamics and therapeutic response. While we can see 4 general types of response to therapy in the clinic (top panel, nonresponse, early relapse, late relapse, and long-term response), the hypothesized underlying intratumoral views (bottom panel) of these scenarios could have significant implications for therapy. If the response of patients to therapeutic intervention is either a long-term response or complete nonresponse, we hypothesize that the underlying genetic diversity is minimal, with clones either homogenously sensitive or homogenously resistant to therapy. Those that initially respond to therapy but relapse early or late after therapy is completed could be examples of either selection for the fittest existing clone (early relapsers, survival of the fittest) or the emergence of new clones generated during (or by) therapy that over time cause another outgrowth of the tumor (late relapsers, secondary clonal evolution). To distinguish which of the evolutionary pressures (resistance, sensitivity, survival of the fittest, or secondary clonal evolution) apply to each clinical manifestation requires additional tools suitable for clinical monitoring of clonal diversity and clonal identities. (Figure by Dr. Amy Paguirigan).

The advent of single-cell genotyping has furthered this evolutionary focus, replacing the estimation of clonal structure from bulk sequencing of a leukemia sample with clonal population determinations based on counting the mutations in each cell.29-32 These studies support the concept of branching evolution suggested by bulk sequencing but up the ante: single-cell analyses show a shocking amount of genetic complexity, with multiple clones including various combinations of functionally distinct mutations arising per cell. Darwinian concepts are found, including exclusion of like-functioning mutations in the same cell (eg, no N-RAS and K-RAS in the same cell), convergent evolution (similar mutations arising in different clonal trees), and selection and expansion of clones after the selective pressure of chemotherapy. Additionally, an approach of combining lineage detection and patient-specific target amplification has suggested the ability to tease apart prior CHIP clones with clones evolving to AML after subsequent mutations are acquired.33

Conclusion: MRD in a 2-by-2 table

Let us return to the most basic problem with MRD: despite being the most powerful predictor of relapse, it still suffers from a very high rate of false positives (MRD positive, no relapse) and false negatives (MRD negative, relapse). Simplifying the problem into a 2-by-2 table (Table 1) allows us to make quick intuitive sense of the concordant cases (MRD-positive patients who relapse, MRD-negative patients who do not)—the test works! However, what about the discordant cases?

MRD and relapse made simple

| . | Relapse status . | |

|---|---|---|

| MRD status . | Yes . | No . |

| Yes | Disease persists Test works! | Mutations not responsible for pre-malignant transformation and/or Mutation present in lineage not prone to leukemia and/or Active immune suppression and/or Other molecular reprogramming that prevents progression |

| No | Insufficient test sensitivity and/or Genetic marker instability and/or New clone/disease | No evidence of disease Test works! |

| . | Relapse status . | |

|---|---|---|

| MRD status . | Yes . | No . |

| Yes | Disease persists Test works! | Mutations not responsible for pre-malignant transformation and/or Mutation present in lineage not prone to leukemia and/or Active immune suppression and/or Other molecular reprogramming that prevents progression |

| No | Insufficient test sensitivity and/or Genetic marker instability and/or New clone/disease | No evidence of disease Test works! |

MRD-negative patients who relapse

The simplest explanation is that we need a more sensitive assay to detect malignant clones (the better mousetrap solution). This is best supported by the study noted above directly comparing the very sensitive duplex sequencing assay with flow cytometry, which doubled the odds ratio of relapse. Another possibility is that a clone might become detectable at relapse that was not present during MRD assessment (eg, FLT3-ITD). However, unless the time of MRD assessment and relapse was long, this would seem unlikely for the evolution of a new clone, but rather might still fall under a limit of detection issue.

MRD-positive patients who do not relapse

The most obvious possibility here is the persistence of mutations that occurred in a “premalignant” state—for example, from CHIP, or in a case of known (or unknown) antecedent MDS. However, while these may persist and may not relapse within a relatively short time frame, it seems caution would apply (if I were a betting man, I would lay odds that an AML having a persisting DTA mutation after therapy has a worse hematological future than an age-matched me). Another possibility is lineage spillover—that is, the mutation being present in nonmyeloid cells (eg, lymphoid), producing a positive signal in a lineage that will not contribute to relapse. This has been seen in MDS and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) on the level of chromosomal aberrations and in some single-cell studies where mutations and lineage can be simultaneously studied.

There are several remaining issues that might further enhance our understanding of disease response, MRD, and relapse. Among these include whether different mutations have different quantitative thresholds (eg, a mutation in gene X might be permissible at a variant allele frequency of 0.1%, while in gene Y, any evidence of persistence portends relapse). In addition, for any given clone size, different combinations of mutations may have different implications. Lastly, the order of mutation acquisition may influence the biology of response and relapse.

While much of this article's emphasis has been on exploring the shortcomings of MRD and on how understanding clonal dynamics might improve the clinical impact of MRD detection, given the complexity of cancer therapy—the genetic and phenotypic qualities of the leukemia, the host factors' influence on the therapy, the impact of the microenvironment and the immune system—perhaps we instead should be marveling at how well MRD performs, after all.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Jerald Radich: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Jerald Radich: Nothing to disclose.