Abstract

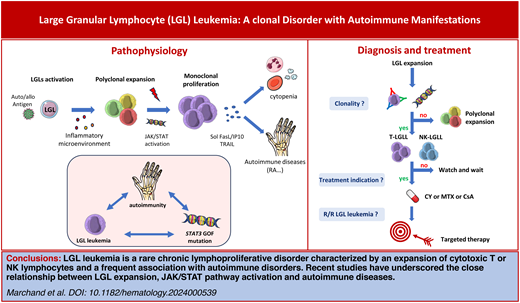

Large granular lymphocyte (LGL) leukemia is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by an expansion of clonal T or natural killer lymphocytes. Neutropenia-related infections and anemia represent the main manifestations. LGL leukemia is frequently associated with autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren's syndrome, autoimmune endocrinopathies, vasculitis, or autoimmune cytopenia. Recent advances in the phenotypic and molecular characterization of LGL clones have underscored the pivotal role of a chronic antigenic stimulation and a dysregulation of the Jak/STAT signaling pathway in the pathophysiology linking leukemic-cell expansion and autoimmunity. In more than half of patients, there is a somatic STAT3 mutation. The disease is characterized by an indolent course, but approximately half of all patients will eventually require therapy. The first-line treatment for LGL leukemia is historically based on immunosuppressive agents (methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, or cyclosporine). However, cytokines blocking molecules or Jak/STAT inhibitors represent a new conceptual therapeutic approach for LGL leukemia. In this review, we present an overview of the spectrum of LGL proliferations, potential links between LGL expansion and autoimmunity, and therapeutic approaches.

Learning Objectives

Delineate the spectrum of LGL proliferations

Understand potential mechanisms of associated autoimmune diseases in the context of LGL proliferations

Propose an appropriate therapy in LGL leukemia

CLINICAL CASE

A 62-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has been treated with methotrexate (MTX) and prednisone for the past 2 years. While control of the disease has been adequate over the last year, blood cell counts have demonstrated a progressive decline in the absolute neutrophil count below 0.6 g/L despite the recent cessation of MTX, with lymphocytosis at 5.2 g/L comprising 1.9 g/L of large granular lymphocytes (LGLs). The patient reported recurrent stomatitis and has had 2 recent episodes of fever requiring antibiotics. Clinical examination revealed an enlarged spleen. Her hemoglobin level was 11.5 g/dL and her platelet count 145 g/L. Prior to the implementation of a novel therapeutic approach, a diagnostic procedure was required.

Diagnosis, classification, and molecular events of LGL proliferations

Diagnosis

The diagnostic procedures aim to differentiate reactive LGL expansion from LGL leukemia. Reactive polyclonal LGL expansion can be seen in various situations, such as viral infections (cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, etc), after splenectomy, and after organ or stem cell transplantation.

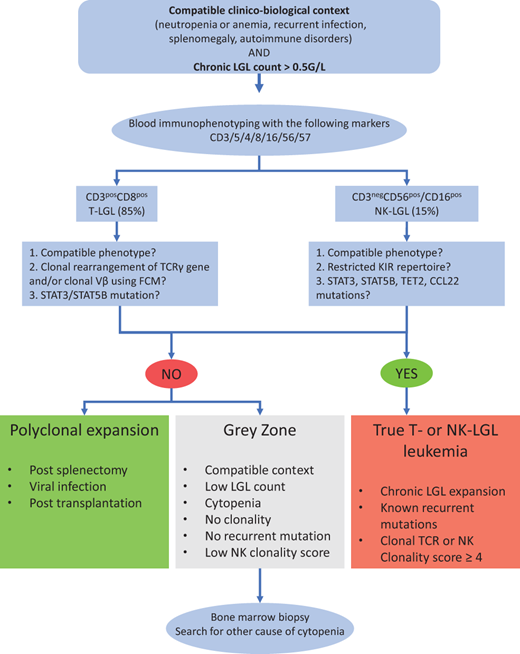

The diagnosis is based on 2 mandatory criteria: (1) the identification of an elevated number of circulating LGL cells (>0.5 × 109/L) and/or a compatible phenotypic pattern and (2) a proof of clonality obtained by flow cytometry and/or molecular biology. The diagnosis workflow is presented in Figure 1. Large granular lymphocytes are easily identified on a blood smear. These large cells (15-20 µm) are characterized by abundant cytoplasm containing azurophilic granules and a reniform or round nucleus with mature chromatin. In a normal setting, LGLs represent 10%-15% of mononuclear cells (ie, 0.21-0.29 LGL × 109/L). Leukemic and normal LGLs are morphologically indistinguishable, justifying phenotypic analyses when LGL leukemia is suspected. Caution is warranted in the case of normal lymphocyte count. Blood analyses are typically sufficient to ascertain the diagnosis. Bone marrow exploration is recommended in cases of low LGL count (<1 × 109/L) or associated confounding conditions such as pure red-cell aplasia (PRCA) or myelodysplasia. Histological analysis typically reveals intrasinusoidal linear clusters of LGLs that are CD8+, granzyme B+, and TIA1+.1

Workflow for the diagnostic procedure of LGL leukemia. CCL22, C-C motif chemokine ligand 22; KIR, killer- cell immunoglobulin-like receptors.

Workflow for the diagnostic procedure of LGL leukemia. CCL22, C-C motif chemokine ligand 22; KIR, killer- cell immunoglobulin-like receptors.

Neutropenia is observed in 70%-85% of cases, with a higher incidence in T-LGL leukemia compared to its natural killer (NK) counterpart.2 Anemia is moderate and fewer than 10%-20% of patients are transfusion dependent. PRCA affects 5%-7% of patients in the West and up to 40% in Asia. The pathogenesis of PRCA in LGL leukemia involves T-cell dysregulation with the activation of cytotoxic T cells and the direct destruction of erythroid precursors. Hemolytic anemia and immune thrombocytopenia have occasionally been reported. Thrombocytopenia, usually moderate, is observed in fewer than 20% of patients. Bone marrow involvement, observed in 70%-90% of cases, is unlikely to contribute directly to cytopenias as infiltration is subtle in the majority of patients. Lymphocytosis is inconsistent, and the LGL threshold was lowered to 0.5 × 109/L even though the 2 × 109/L threshold is still retained as a diagnostic criterion in the last 2022 International Consensus Classification and World Health Organization classifications.3,4 Serum electrophoresis frequently shows hypergammaglobulinemia. Antinuclear antibodies are seen in 20%. Increased ß2-microglobulin and soluble Fas-L are observed in 65% and 95%, respectively.

LGL leukemia has a CD3+ T-cell phenotype in 85% of diagnoses, whereas its CD3− CD56+/CD16+ NK counterpart represents 15% of cases. In most cases, leukemic T LGLs display a terminal effector memory T-cell phenotype (T-cell receptor αβ [TCRαβ]+ CD45+ D8+ CD57+ CD16+ CD62L−) and an aberrant dim expression of CD5.5 TCRγδ-LGL leukemia with a CD4− CD8− phenotype is observed in approximately 15% of cases.6 The demonstration of clonality represents a pivotal step in the diagnosis of T-LGL leukemia. TCR Vβ analysis by flow cytometry can be employed as a surrogate marker of TCR clonality with commercially available antibodies that cover approximately 70% of the Vβ repertoire.7 Nevertheless, polymerase chain reaction using primers targeting the conserved region of the VDJ segments remains the gold standard to demonstrate a clonal rearrangement of the TCRγ gene. In TCRαβ+ LGL, flow cytometry–based analysis of the constant region 1 of the TCRβ chain (TCRBC1) has been recently developed with high sensitivity and good correlation with the TCR sequencing.8

In NK-LGL leukemia, leukemic cells typically display the following phenotype: CD2+ sCD3− CD3ε+ TCRαβ− CD4− CD8+ CD16highCD56low. However, phenotypic analysis does not easily allow the distinction between normal and leukemic NK cells. In contrast with T-LGL leukemia, the demonstration of clonality in chronic NK-LGL is considerably more challenging due to the lack of TCR expression in NK cells. A restricted killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors repertoire has been employed as a surrogate marker of clonality, and we recently developed an NK clonality score to distinguish authentic NK-LGL leukemia from reactive NK-LGL expansion.9

Classification

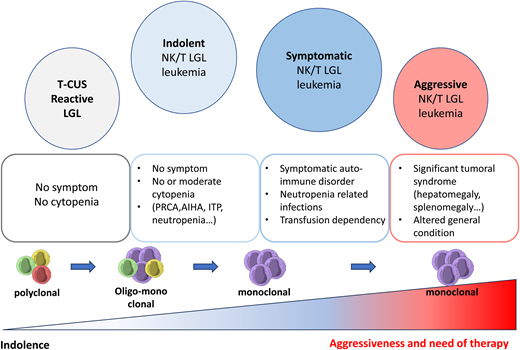

LGL leukemias are divided in 2 categories, T-LGL (85%) and NK-LGL subtypes (15%). The most common subtypes of T-LGL leukemias are CD3+ αβ+ CD8+ CD57+ (80%), CD3+ γδ+ CD4− CD8− (15%), and more rarely CD3+ αβ+ CD4+ CD8+ (5%). Beside this “hematological” classification, the border between LGL leukemia and T-cell clonal associated diseases is highly debated. It has become evident that autoimmune diseases may share biological similarities with LGL leukemia (T-cell expansion, STAT3 mutation, secretion of proinflammatory cytokines). The term T-cell clones of uncertain significance has been proposed to describe a clinical situation in which patients have persistent oligoclonal/monoclonal effector memory T-cell expansion (mimicking leukemic LGL) in the absence of clinical or biological features that would allow the diagnosis of T-LGL leukemia (Figure 2).10

Spectrum of LGL expansion ranging from reactive LGL to an aggressive form of LGL leukemia. AIHA, auto-immune hemolytic anemia; ITP, immune thrombocytopenia; T-CUS, T-cell clones of uncertain significance.

Spectrum of LGL expansion ranging from reactive LGL to an aggressive form of LGL leukemia. AIHA, auto-immune hemolytic anemia; ITP, immune thrombocytopenia; T-CUS, T-cell clones of uncertain significance.

Molecular events and the key role of STAT3 mutation

Since the discovery of the constitutive activation of STAT3 in 2001 as the hallmark of LGL leukemia, several mutations have been identified that affect key T-cell cellular functions, including cytokine secretion, proliferation, apoptosis, and epigenetics.11,12STAT3 gain-of-function mutations have been identified in up to 60% of T-LGL and 30% of NK-LGL subtypes, unifying both entities.13,14 These mutations induce constitutive dimerization and phosphorylation of STAT3, resulting in the increased transcription of antiapoptotic genes (BCLXL, FLIP), cell-cycle genes (CDKN1D, CMYC), and proinflammatory cytokine coding genes (IL-6, IL-12, IL-17, IL-21, IL10 and immune interferon [IFN-γ]). A STAT3 gain-of-function mutation results in a more cytotoxic profile, a higher blood LGL level, deeper cytopenia, and an increased incidence of RA.15 In addition to STAT3, mutations in STAT5B have been reported, mainly occurring in the rare indolent form of CD4+ Tαβ-LGL leukemia (45%) and in Tγδ-LGL leukemia (6%).16 In T-LGL leukemia, mutations of the histone monomethyltransferase KMT2D are detected in up to 20% of cases. Epigenetic modifications including DNA methylation alterations seem to be a crucial event in NK-LGL leukemia, as evidenced by the high prevalence of TET2 (10-11-translocation 2) mutations in this subtype, which are present in 28%-34% of NK-LGL leukemia patients.9,17 There is mounting evidence that the microenvironment plays a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Gain-of-function in the CCL22 gene mutations are observed in 27% of NK-LGL subtypes and are mutually exclusive of STAT3 mutations.18 These alterations induce a defect in CCR4 internalization in targeted cells, resulting in increased cellular chemotaxis and dysregulated cross talk with the hematopoietic microenvironment. Nonleukemic immune cells have also recently been implicated in the pathogenesis of the disease. Indeed, single-cell analysis revealed that IFN-γ response genes were upregulated in various immune cells, including nonleukemic NK cells and monocytes.19 Monocytes have been shown to support leukemic T-LGL growth, and an abnormal monocyte distribution has been observed in symptomatic patients.20

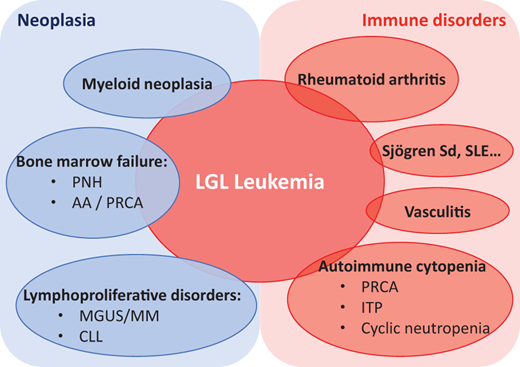

Spectrum of autoimmune diseases with LGL leukemia

LGL leukemia lies at the interface between neoplasia, hematology and autoimmunity, with autoimmune disorders reported in 25%-32% of cases (Table 1 and Figure 3).21 RA represents the main autoimmune disorder associated with LGL leukemia, affecting 10%-15% of patients, a prevalence not coincidental.2,22,23 RA is more common in the T-LGL subtype, and the severity of the disease appears similar to that seen in canonical RA. Two-thirds of patients with RA and LGL leukemia are female. Several other autoimmune disorders have been described, mostly sporadically. Sjögren's syndrome, rhizomelic pseudopolyarthritis, and unclassified inflammatory arthritis have also been described.24 Vasculitis, including cryoglobulinemia, cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–negative microscopic polyangiitis, and pulmonary artery hypertension have been reported.25-27 Occasionally, systemic lupus erythematosus and inclusion body myositis have been reported. The regression of autoimmune manifestations following the treatment of LGL leukemia highlights the close relationship between these 2 conditions.26,27

Spectrum of LGL leukemia and associated diseases. AA, aplastic anemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; ITP, immune thrombocytopenia; MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM, multiple myeloma; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; Sjögren Sd, Sjögren syndrome; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Spectrum of LGL leukemia and associated diseases. AA, aplastic anemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; ITP, immune thrombocytopenia; MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM, multiple myeloma; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; Sjögren Sd, Sjögren syndrome; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Principal diseases associated with LGL leukemia

| Autoimmune disorders . | Prevalence . | |

|---|---|---|

| Joint disorders | RA | 10%-18% |

| Rhizomelic pseudopolyarthritis | Sporadic | |

| Unclassified inflammatory arthritis | Sporadic | |

| Endocrinopathies | Hashimoto's disease | Sporadic |

| Cushing's syndrome | Sporadic | |

| Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome | Sporadic | |

| Connective tissue disorders | Sjögren's syndrome | 13% |

| Uveitis | Sporadic | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Sporadic | |

| Muscular and neurological disorders | Polymyositis | Sporadic |

| Inclusion body myositis | Sporadic | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Sporadic | |

| Lambert-Eaton syndrome | Sporadic | |

| Myasthenia gravis | Sporadic | |

| Skin disorders | Psoriasis | Sporadic |

| Livedoid vasculopathy | Sporadic | |

| Cutaneous vasculitis | Sporadic | |

| Cutaneous papules and nodules | Sporadic | |

| Vasculitis | Small-vessel vasculitis | Sporadic |

| Type 1/2 cryoglobulinemia vasculitis | Sporadic | |

| Glomerulonephritis | Sporadic | |

| Pulmonary artery hypertension | Sporadic | |

| Bowel disorders | Celiac disease | Sporadic |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Sporadic | |

| Immunodeficiencies | Good syndrome | Sporadic |

| Adenosine deaminase deficiency | Sporadic | |

| Immune cytopenia | PRCA | 5%-7%a |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | Sporadic | |

| Immune thrombocytopenia | 1%-2% | |

| Evans syndrome | Sporadic | |

| Autoimmune disorders . | Prevalence . | |

|---|---|---|

| Joint disorders | RA | 10%-18% |

| Rhizomelic pseudopolyarthritis | Sporadic | |

| Unclassified inflammatory arthritis | Sporadic | |

| Endocrinopathies | Hashimoto's disease | Sporadic |

| Cushing's syndrome | Sporadic | |

| Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome | Sporadic | |

| Connective tissue disorders | Sjögren's syndrome | 13% |

| Uveitis | Sporadic | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Sporadic | |

| Muscular and neurological disorders | Polymyositis | Sporadic |

| Inclusion body myositis | Sporadic | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Sporadic | |

| Lambert-Eaton syndrome | Sporadic | |

| Myasthenia gravis | Sporadic | |

| Skin disorders | Psoriasis | Sporadic |

| Livedoid vasculopathy | Sporadic | |

| Cutaneous vasculitis | Sporadic | |

| Cutaneous papules and nodules | Sporadic | |

| Vasculitis | Small-vessel vasculitis | Sporadic |

| Type 1/2 cryoglobulinemia vasculitis | Sporadic | |

| Glomerulonephritis | Sporadic | |

| Pulmonary artery hypertension | Sporadic | |

| Bowel disorders | Celiac disease | Sporadic |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Sporadic | |

| Immunodeficiencies | Good syndrome | Sporadic |

| Adenosine deaminase deficiency | Sporadic | |

| Immune cytopenia | PRCA | 5%-7%a |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | Sporadic | |

| Immune thrombocytopenia | 1%-2% | |

| Evans syndrome | Sporadic | |

In the West and 29%-48% in Asia.

AIHA, autoimmune hemolytic anemia; ITP, immune thrombocytopenia; T-CUS, T-cell clones of uncertain significance.

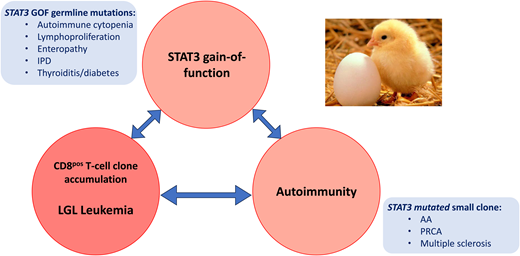

The question of whether autoimmune disorders are a cause or a consequence of LGL leukemia is a matter of ongoing debate that has been likened to the “chicken or the egg” conundrum (Figure 4). Indeed, in both conditions an autoantigen or pathogen- derived antigen has been postulated as an initiating event. There is a clear association between RA and LGL leukemia. Activation of the janus kinase/STAT (Jak/STAT) pathway and inflammatory cytokines are implicated in the pathogenesis of both diseases. Patients with RA and those with RA and LGL leukemia share a proinflammatory cytokine profile (IFN-γ, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor α, IL-6, IL-12, IL-15 and IL-18), as well as the presence of anticitrullinated protein antibodies. In 90% of cases, patients with both diseases display an HLA-DR4 phenotype, in comparison to 30% of RA patients without LGL disease. Effector memory cytotoxic T cells, phenotypically identical to LGL cells, have been found in the synovium of RA patients. However, no STAT3 mutations have been identified in RA patients without LGL leukemia.28 Usually, RA precedes the onset of LGL leukemia. It is therefore plausible that it may contribute to the clonal expansion of LGL, at least in patients affected by both diseases. In LGL leukemia, RA is more frequently observed in patients harboring multiple STAT3 mutations.29

Links between STAT3 mutation, autoimmune conditions, and LGL expansion. AA, aplastic anemia; GOF, gain-of-function; IPD, inherited photoreceptor degeneration.

Links between STAT3 mutation, autoimmune conditions, and LGL expansion. AA, aplastic anemia; GOF, gain-of-function; IPD, inherited photoreceptor degeneration.

STAT3 gain-of-function mutations have been observed in several autoimmune diseases associated with a CD8+ T-cell expansion, including aplastic anemia, PCRA, and multiple sclerosis. Furthermore, the majority of patients with a germline STAT3 gain-of-function mutation present with lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmune disorders, including autoimmune cytopenia, vasculitis, and arthritis.30 In a mouse model, STAT3 gain-of- function induced the expansion of NKG2D+ CD8+ CD62L− CD44+ T cells and the overexpression of cell-cycle and killer-cell genes (GZMA and GZMB) through NKG2D/IL-2-IL-15 receptor interactions.31 While current opinion holds that autoimmune disease and LGL leukemia may both arise from a common proinflammatory context, this study demonstrates that the LGL clone itself may play a crucial role in autoimmunity development. In fact, it appears that different subsets of STAT3 mutations may cause the accumulation of oligoclonal CD8 cytotoxic cells that are closely related to LGL and participate in autoimmune manifestations.

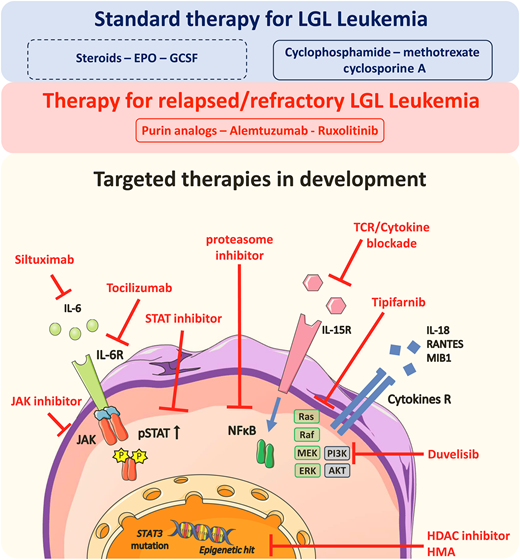

Treatment of LGL leukemia

LGL leukemia remains an indolent but incurable disease. In the largest retrospective studies, the 10-year overall survival is above 70%.2,22,23 There is no difference in the treatment strategy between T-LGL and NK-LGL subtypes. Before starting cytotoxic or immunosuppressive therapy, symptomatic anemia may be supported by erythropoietin. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor may be proposed for acute severe infection-associated neutropenia but is not routinely recommended for a long period of time.

When should treatment be initiated?

A watch-and-wait strategy can be proposed in approximately half of the cases at diagnosis. However, most patients will eventually require treatment during their lifetime. Severe neutropenia (neutrophils <0.5 × 109/L), neutropenia-related infections, and transfusion-dependent and symptomatic anemia represent the main indications. Autoimmune disorders may indicate the need for treatment even in the absence of symptomatic cytopenia.

How and when should the response to treatment be evaluated?

It is recommended that the response to immunosuppressive therapy be evaluated between month 4 and 6 after initiation. The evaluation of the treatment response is primarily based on blood parameters and transfusion dependency.

First-line treatment

Single-agent cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), MTX, and cyclosporine are the 3 recommended drugs in first-line treatment. There is no consensus regarding the optimal treatment sequence. Overall response rates (ORRs) reported with the 3 available drugs range from 38 to 75% depending on the retrospective or prospective nature of the studies. Only 2 prospective studies have been conducted in naive patients. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study reported an ORR of 38% after MTX.32 A total of 166 patients have been enrolled in the prospective randomized study comparing cyclophosphamide and MTX in France (NCT01976182).33 The results of the interim analysis performed on the first 96 patients showed an ORR to the first line of 55% at 4 months with only 16% complete remission and a high rate of relapse occurring in 67% of the cohort. MTX (10 mg/m2/wk) and cyclosporine A (3 mg/kg/d) are typically administered until progression, whereas cyclophosphamide should not be administered for more than 1 year due to the mutagenic risk. Cyclophosphamide or cyclosporine may be more suitable for patients with anemia, particularly PRCA. MTX is appropriate for patients with RA due to its efficacy in both conditions. In the absence of response to 1 drug, a switch is recommended. Cyclophosphamide and MTX are generally considered the best first-line option. Cyclosporine A is typically considered for LGL leukemia patients with aplastic anemia or those who have failed both drugs. A retrospective study including 60 patients in second-line treatment reported a 70% ORR with cyclophosphamide.34 In contrast, MTX was not effective in patients failing cyclophosphamide.

Treatment in relapsed/refractory disease

Several approaches have been evaluated in patients refractory to the 3 main immunosuppressive drugs. Alemtuzumab has been used with promising results (56% ORR; 95% CI, 35-76), although it is associated with high toxicity (7 deaths out of 25 patients).35 Bendamustine and purine analogues, such as fludarabine and cladribine, have demonstrated interesting response rates in small retrospective studies.2,36 In patients with aplastic anemia, antithymocyte globulins, either alone or in combination with cyclosporine A, have led to some responses. Autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantations have been employed infrequently in highly pretreated and refractory patients.

Given the pivotal role of the Jak/STAT pathway in the pathogenesis of LGL leukemia, JAK inhibitors represent an attractive option. In 2015, tofacitinib, a Jak3 inhibitor, demonstrated partial efficacy in LGL leukemia patients with associated RA, although this was accompanied by significant toxicity.37 We initially reported the efficacy of ruxolitinib in 2 patients with refractory T-LGL leukemia and more recently published the retrospective analysis of a series of 21 patients showing an 85% ORR, including patients with complete clinical and molecular remission.38 The efficacy of ruxolitinib was recently confirmed in a prospective phase 2 clinical trial.39 In 20 patients with refractory/relapsed disease, the ORR and complete response rate were respectively 55% and 30%. Interestingly, STAT3 mutational status was predictive of event-free survival, with a 14-month event-free survival of 100% in the mutated patients compared to 40% in the nonmutated patients.

Future therapeutic directions

BNZ-1, a pegylated peptide that selectively inhibits the binding of IL-15 and other γc cytokines to their receptors, was prospectively evaluated in a phase 1/2 clinical trial showing a 20% ORR.40 A phase 1 study evaluating siltuximab is currently underway (NTC05316116). The role of hypomethylating agents is currently being evaluated in a phase 1 study with oral azacitidine (NCT05141682). A phase 1/2 trial is currently underway to assess the safety and efficacy of DR-01, a nonfucosylated antibody targeting the CD94 lectin receptor (NCT05475925). Similarly, ABC008 is a first-in-class monoclonal antibody targeting the coinhibitory T-cell receptor killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 and was tested in a phase 1/2 trial (NCT05532722). Specific STAT inhibitors have been developed. KT-333 is a STAT3 degrader currently being evaluated in a phase 1a/1b study (NCT05225584). Given the multiplicity of pathways involved in the pathogenesis of LGL leukemia and the clonal heterogeneity of the disease, it is conceivable that a multidrug approach combining a Jak/STAT inhibitor and a cytokine-targeting agent will be proposed in the near future (Figure 5).

Treatment options for LGL leukemia. AKT, protein kinase B; EPO, erythropoietin; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GCSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HMA, hypomethylating agents; IL, interleukin; IL-R, interleukin receptor; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; MIB1, Mindbomb E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1; NFKB, nuclear factor-kappa B; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; RANTES, regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted.

Treatment options for LGL leukemia. AKT, protein kinase B; EPO, erythropoietin; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GCSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HMA, hypomethylating agents; IL, interleukin; IL-R, interleukin receptor; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; MIB1, Mindbomb E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1; NFKB, nuclear factor-kappa B; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; RANTES, regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient presented with a CD3+ CD5dim CD8+ CD57+ LGL phenotype, and the TCRγ gene rearrangement confirmed the monoclonality. HST sequencing revealed the presence of a STAT3 mutation with a 35% variable allele frequency, confirming the diagnosis of T-LGL leukemia. The patient was treated successfully with cyclophosphamide at 100 mg/d for 4 months, entering complete hematological remission with no RA symptoms while maintaining a prednisone dosage of 5 mg/d. The cyclophosphamide was then tapered to 50 mg/d and discontinued at month 8. The patient remains in complete remission after 3 years of follow-up.

Conclusions

LGL leukemia is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by a large spectrum of clinicobiological manifestations and a peculiar association with autoimmune disorders. Even though single-agent immunosuppressive drugs induce responses in the majority of patients, relapses are frequent, and the disease remains uncurable. Advances in understanding its pathophysiology and the identification of recurrent mutations open the way to developing new therapeutic strategies.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Tony Marchand: no competing financial interests to declare.

Cédric Pastoret: no competing financial interests to declare.

Aline Moignet: no competing financial interests to declare.

Mikael Roussel: no competing financial interests to declare.

Thierry Lamy: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Tony Marchand: Nothing to disclose.

Cédric Pastoret: Nothing to disclose.

Aline Moignet: Nothing to disclose.

Mikael Roussel: Nothing to disclose.

Thierry Lamy: Nothing to disclose.