Abstract

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) do not require routine monitoring of anticoagulant effect, but measuring DOAC activity may be desirable in specific circumstances to detect whether clinically significant DOAC levels are present (eg, prior to urgent surgery) or to assess whether drug levels are excessively high or excessively low in at-risk patients (eg, after malabsorptive gastrointestinal surgery). Routine coagulation tests, including the international normalized ratio (INR) or activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), cannot accurately quantify drug levels but may provide a qualitative assessment of DOAC activity when considering the estimated time to drug clearance based on timing of last drug ingestion and renal and hepatic function. Drug-specific chromogenic and clot-based assays can quantify drug levels but they are not universally available and do not have established therapeutic ranges. In this review, we discuss our approach to measuring DOAC drug levels, including patient selection, interpretation of coagulation testing, and how measurement may inform clinical decision-making in specific scenarios.

Learning Objectives

Review the rationale for measuring DOAC anticoagulant effect with a focus on assessing clinical utility

Summarize the role of routine coagulation tests and drug-specific assays for measuring DOAC anticoagulant effect

Introduction

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), including apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and dabigatran, are widely prescribed for the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in atrial fibrillation, for which they are at least as effective and safe as treatment with warfarin.1,2 Unlike warfarin, DOACs have relatively predictable pharmacokinetics, short-half lives, and a wide therapeutic index, and they are prescribed in fixed doses without the need for routine monitoring.3 However, measuring DOAC anticoagulant effect may be desirable in some circumstances for which the results could change clinical management. The clinical utility remains uncertain due to important challenges that affect how to interpret and apply results to practice, including (1) lack of established therapeutic ranges, (2) no threshold for clinically significant anticoagulant effect, (3) routine coagulation tests not being accurate or reliable, (4) limited availability of specific tests, and (5) uncertainty about how results should change treatment in individual patients. In this article, we provide an approach to rationalize the measurement of DOAC effects in routine practice, including general principles, laboratory testing considerations and interpretation, and common scenarios for which measurement may be helpful.

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 51-year-old man with a history of recurrent, unprovoked deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) on apixaban 5 mg twice a day presents to the emergency department (ED) with intractable abdominal pain due to an incarcerated hernia. His last dose of apixaban was taken 18 hours prior to the ED presentation. Creatinine clearance is 51 mL/min. An apixaban drug level (measured by a drug-specific anti-Xa assay) is 50 ng/mL. The expected peak plasma concentration is 59-302 ng/mL at a steady state. Six hours later, his condition worsens and he requires urgent surgery. Do you recommend preoperative anticoagulant reversal?

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 55-year-old woman with obesity (body mass index [BMI] 42 kg/m2), type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and prior transient ischemic attack (TIA) is diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (CHADS2 score of 4) 1 year after a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). Her mobility is limited, and she has difficulty attending medical or laboratory appointments. What anticoagulant do you recommend for stroke prevention?

Why measure the effect of drugs that do not require routine monitoring?

Although there are no established therapeutic ranges for DOACs, it appears that DOAC levels may influence clinical outcomes. Phase 3 clinical trials of DOACs for atrial fibrillation showed associations between trough drug levels (for edoxaban4 and dabigatran5), prothrombin time (PT; for rivaroxaban3,6), or anticoagulant exposure as measured by area under the curve (AUC; for apixaban) and the risks of stroke or bleeding.3Post-hoc analyses of the RE-LY5 and ENGAGE AF-TIMI 484 trials showed that low trough levels of dabigatran and edoxaban measured at steady-state are correlated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, and analyses of the ROCKET-AF trial6 showed that a prolonged PT among patients taking rivaroxaban predicts a lower risk of stroke. No such relationship was found between apixaban exposure measured by AUC and ischemic stroke in the ARISTOTLE trial.3 In all 4 trials, higher drug levels, prolonged PT, or larger AUC predicted a higher risk of major or life-threatening bleeding during therapy.

While these and other modeling studies suggest that individualized DOAC dosing may ultimately optimize the balance between benefit and harm,7 this approach is not recommended in the absence of high-quality data supporting dose adjustment based on the results of drug levels. First, therapeutic ranges for DOAC drug levels have not been established. Instead, expected on-therapy peak and trough drug levels derived from clinical trials evaluating the use of DOACs in atrial fibrillation and VTE treatment can help clinicians interpret results (Table 1). Second, substantial interpatient and intrapatient variability of DOAC drug levels limits their interpretation at the individual patient level.8-11 Among DOAC-treated patients with atrial fibrillation, there is significant variability in DOAC concentrations reflected by high coefficients of variation (CV) when measured at both peak and trough, within (34% and 37%) and between individuals (46% and 63%).12 In the ARISTOTLE trial, there was a substantial overlap in apixaban levels between patients who did and those who did not experience a major bleed.3 Third, the relationship between drug levels and the risk of stroke or bleeding is confounded by clinical characteristics, especially age, renal function, and body mass, which are already used to reduce DOAC doses to account for decreased drug clearance. Evidence is lacking on how DOAC dosing should be adjusted to achieve desired drug levels within the constraints of available tablet or capsule strengths. Finally, there are no adequately powered randomized trials addressing the impact of dose adjustment according to laboratory monitoring on efficacy and safety. In a prospective registry of 5738 patients treated with DOACs for atrial fibrillation, those receiving an off-label dose reduction experienced a higher risk of cardiovascular hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.26; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07-1.50), and those receiving an off-label dose increase experienced increased all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.02-3.60) compared with patients treated with on-label doses.13 Risks of major bleeding and hospitalization due to bleeding were comparable between dosing groups. These data suggest that patients who are prescribed DOACs at off-label doses are at higher risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes without attenuation of their bleeding risk. RE-ALIGN was a phase 2 dose-validation study that compared dabigatran with warfarin after mechanical heart valve implantation with dose-adjustment of dabigatran to obtain a trough drug level >50 ng/mL.14 The trial was terminated prematurely because of an excess of thromboembolic and bleeding events in patients receiving dabigatran compared to warfarin.

Expected DOAC steady-state peak and trough plasma concentrations

| Direct oral anticoagulant . | Dose . | Expected peak plasma concentration (ng/mL)b . | Expected trough plasma concentration (ng/mL) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apixaban | 5 mg twice daily | 132 (59-302) VTE 171 (91-321) AFib | 103 (41-230) |

| Rivaroxaban | 10 mg once daily | 125 (91-196) | 26 (6-87) |

| 15 mg once daily | 229 (178-313) | ||

| 20 mg once daily | 270 (189-419) VTE 249 (184-343) AFib | ||

| Edoxaban | 30 mg once daily | 164 (99-225) VTE 169 (10-400) Afib | 22 (10-40)c |

| 60 mg once daily | 234 (149-317) VTE 300 (60-569) Afib | ||

| Dabigatran | 110 mg twice daily | 126 (52-275) | 90 (31-225) |

| 150 mg twice daily | 175 (74-383) |

| Direct oral anticoagulant . | Dose . | Expected peak plasma concentration (ng/mL)b . | Expected trough plasma concentration (ng/mL) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apixaban | 5 mg twice daily | 132 (59-302) VTE 171 (91-321) AFib | 103 (41-230) |

| Rivaroxaban | 10 mg once daily | 125 (91-196) | 26 (6-87) |

| 15 mg once daily | 229 (178-313) | ||

| 20 mg once daily | 270 (189-419) VTE 249 (184-343) AFib | ||

| Edoxaban | 30 mg once daily | 164 (99-225) VTE 169 (10-400) Afib | 22 (10-40)c |

| 60 mg once daily | 234 (149-317) VTE 300 (60-569) Afib | ||

| Dabigatran | 110 mg twice daily | 126 (52-275) | 90 (31-225) |

| 150 mg twice daily | 175 (74-383) |

Adapted from Rottenstreich et al, J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2018;45(4):543-549; Gosselin et al, Thromb Haemost. 2018;118(3):437-450; Ezekowitz et al, Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(9):1419-1426; Mueck et al, Clin Phrarmacokinet. 2014;53(1):1-16; Weitz et al, Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(3):633-641.

Peak plasma concentrations are expressed as median (5th-95th percentile range) with the exception of dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, which is expressed as median (10th-90th percentile range).

Interquartile range.

AFib, atrial fibrillation.

Studies examining DOAC drug level ordering patterns reveal equipoise on how drug levels are used in clinical practice and whether they influence management.15-17 In 1 single-center retrospective study, changes to anticoagulation were made in only 2 of 8 patients in whom drug levels were ordered for bleeding and in only 2 of 10 patients who had drug levels measured for breakthrough thrombosis.16 In another study of 119 patients, clinical decisions regarding DOAC management, including dose adjustments, changes in antithrombotic therapy, and drug discontinuation, occurred in one-third of DOAC drug level measurements performed.17

How to interpret coagulation tests in patients treated with DOACs

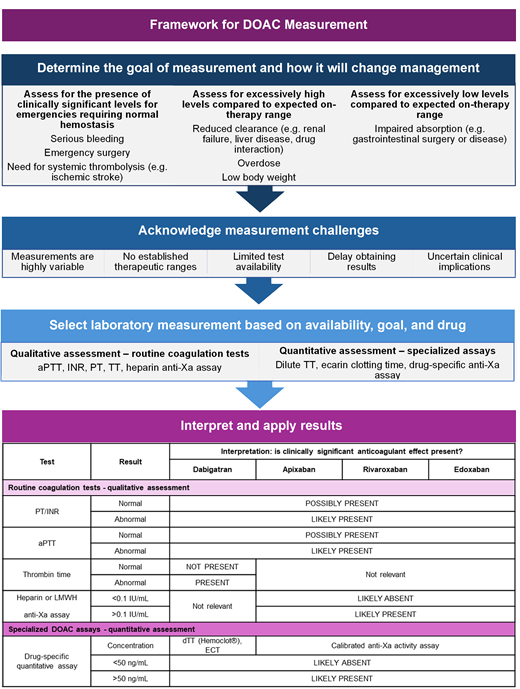

Routine coagulation tests (eg, PT, international normalized ratio [INR], activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT]) are not accurate or reliable for quantification of DOAC concentrations but may provide a qualitative assessment of clinically significant DOAC levels when incorporating the timing of last ingestion and estimated drug clearance (eg, considering renal function, hepatic function, drug interaction). DOAC-specific assays can quantify DOAC concentrations, but they are not universally available (especially on an urgent basis), nor are there established therapeutic ranges for determining whether measured concentrations are appropriate in individual patients.

Qualitative measurements of DOAC anticoagulant effect

In general, routine coagulation tests (including INR and aPTT) are not sufficiently sensitive to reliably detect clinically significant levels of factor Xa inhibitors or dabigatran (ie, levels in the on-therapy range), and there is substantial variability between assays18 (Table 2). The INR and aPTT also lack specificity; these tests may be abnormal for reasons unrelated to DOAC exposure, including liver disease, disseminated intravascular coagulation, massive transfusion, vitamin K deficiency, or preanalytic laboratory error.

Practical approach to interpreting lab tests in the presence of DOACs

| Test . | Result . | Interpretation: is clinically significant anticoagulant effect present? . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dabigatran . | Apixaban . | Rivaroxaban . | Edoxaban . | ||

| Routine coagulation tests - qualitative assessment . | |||||

| PT/INR | Normal | ← POSSIBLY PRESENT → | |||

| Abnormal | ← LIKELY PRESENT → | ||||

| aPTT | Normal | ← POSSIBLY PRESENT → | |||

| Abnormal | ← LIKELY PRESENT → | ||||

| Thrombin time | Normal | NOT PRESENT | ← Not relevant → | ||

| Abnormal | PRESENT | ||||

| Heparin or LMWH Anti-Xa assay | <0.1 IU/mL | Not relevant | ← LIKELY ABSENT → | ||

| >0.1 IU/mL | ← LIKELY PRESENT → | ||||

| Specialized DOAC assays—quantitative assessment | |||||

| Drug-specific quantitative assay | Concentration | dTT (Hemoclot®), ECT | Drug-specific anti-Xa activity assay | ||

| <50 ng/mL | ← LIKELY ABSENT → | ||||

| ≥50 ng/mL | ← LIKELY PRESENT → | ||||

| Test . | Result . | Interpretation: is clinically significant anticoagulant effect present? . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dabigatran . | Apixaban . | Rivaroxaban . | Edoxaban . | ||

| Routine coagulation tests - qualitative assessment . | |||||

| PT/INR | Normal | ← POSSIBLY PRESENT → | |||

| Abnormal | ← LIKELY PRESENT → | ||||

| aPTT | Normal | ← POSSIBLY PRESENT → | |||

| Abnormal | ← LIKELY PRESENT → | ||||

| Thrombin time | Normal | NOT PRESENT | ← Not relevant → | ||

| Abnormal | PRESENT | ||||

| Heparin or LMWH Anti-Xa assay | <0.1 IU/mL | Not relevant | ← LIKELY ABSENT → | ||

| >0.1 IU/mL | ← LIKELY PRESENT → | ||||

| Specialized DOAC assays—quantitative assessment | |||||

| Drug-specific quantitative assay | Concentration | dTT (Hemoclot®), ECT | Drug-specific anti-Xa activity assay | ||

| <50 ng/mL | ← LIKELY ABSENT → | ||||

| ≥50 ng/mL | ← LIKELY PRESENT → | ||||

anti-Xa, anti-Xa activity assay; dTT, dilute thrombin time; ECT, ecarin clotting time.

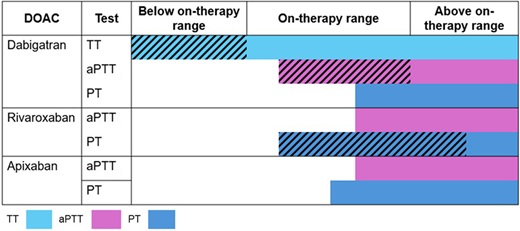

Factor Xa inhibitors prolong the prothrombin time (PT) or aPTT to variable degrees depending on the specific drug (Figure 1), laboratory reagent, and coagulation instrument used for testing.19 An elevated INR or prolonged aPTT in a patient taking a factor Xa inhibitor suggests that a clinically significant factor Xa inhibitor drug level may be present, but these tests should not be used to rule out DOAC exposure (low sensitivity).

Sensitivity and linearity of coagulation assays to DOAC concentrations. Horizontal colored bars correspond to the approximate range of detectability of each assay (ie, sensitivity) below, within, and above expected on-therapy ranges. Diagonal hatching indicates linear relationship between coagulation assay and DOAC concentration within the range. Ranges are approximations and may vary based on assay, reagents, and analyzer. Adapted from Cuker et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1128-1139.

Sensitivity and linearity of coagulation assays to DOAC concentrations. Horizontal colored bars correspond to the approximate range of detectability of each assay (ie, sensitivity) below, within, and above expected on-therapy ranges. Diagonal hatching indicates linear relationship between coagulation assay and DOAC concentration within the range. Ranges are approximations and may vary based on assay, reagents, and analyzer. Adapted from Cuker et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1128-1139.

Studies evaluating thromboelastography (TEG) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) show that R times and clot formation times correlate with dabigatran and rivaroxaban serum concentrations,20 but testing is insensitive to detecting trough DOAC drug levels.21 The International Council of Standardization of Hematology (ICSH) advises against the routine use of TEG or ROTEM for measuring the anticoagulant effect of DOACs.22

The thrombin time (TT) and aPTT have complementary test characteristics for determining the presence of dabigatran. A normal TT excludes dabigatran exposure (very high sensitivity, but low specificity), whereas a prolonged aPTT confirms that dabigatran is present at a potentially clinically meaningful concentration (high specificity, low sensitivity).22

Anti-Xa assays calibrated with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) are highly sensitive to the presence of oral factor Xa inhibitors and correlate linearly with drug levels in the therapeutic range.23 To accurately interpret results, clinicians should be aware of the specific DOAC the patient is taking and ensure the sample is not contaminated with unfractionated heparin (UFH) or LMWH. An undetectable or very low UFH or LMWH anti-Xa level (<0.1 IU/mL) virtually rules out the presence of a factor Xa inhibitor.22 However, results should be interpreted with caution when the goal is to exclude clinically important drug levels in the range of >30-50 ng/mL. One exploratory study24 showed that an apixaban drug level >50 ng/mL corresponded to a LMWH anti-Xa level anywhere between >0.28 to 0.88 U/mL depending on the specific instrument-reagent combination used for testing. For rivaroxaban, the corresponding LMWH anti-Xa threshold ranged from 0.41 to 1.45 U/mL. Differences in chromogenic substrate and factor Xa origin might explain why some assays are more sensitive to the presence of oral factor Xa inhibitors than others.22 These findings highlight the need for local laboratory validation before the routine use of heparin-calibrated assays for this purpose.

Quantitative measurements of DOAC drug levels

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) remains the gold standard and the most accurate means of measuring DOAC drug levels, but it is not used in clinical practice due to lack of instrument availability, labor-intensive sample preparation, and complexity of the technique, all of which limit its widespread use.22 Drug-specific chromogenic and clot-based assays can quantify DOAC drug-level quantitation but are not universally available in all clinical laboratories. Non-specific chromogenic anti-Xa assays are not specific for DOAC measurement, as the anti-Xa level will also be elevated in the presence of UFH, LMWH, or fondaparinux.

When to measure a drug level: clinical utility of testing

The clinical utility of DOAC measurement for decision-making and patient care depends on the goal(s) of testing, which can be conceptualized as follows: (1) to determine whether excessively high levels are present (eg, suspected bioaccumulation or overdose, drug-drug interaction), (2) to determine whether excessively low levels are present (eg, suspected therapeutic failure, confirming adherence, drug-drug interaction, or after malabsorptive gastrointestinal surgery), or (3) to determine whether DOAC concentration is likely sufficient to impair hemostasis (eg, guide anticoagulant reversal for major bleeding or urgent surgery, or use of systemic thrombolysis).19 Specific clinical scenarios for which drug level measurement may inform clinical management are shown in Table 3.

Clinical scenarios in which DOAC drug level measurement may inform clinical management

| Scenario . | Rationale . | Timing of measurement . | Potential impact on clinical decision-making . |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOAL: To assess whether a clinically significant DOAC level is likely to be present in an emergency requiring normal hemostasis | |||

| Prior to an urgent invasive procedure with high bleeding risk | Based on limited data, a DOAC drug level <30 ng/mL is unlikely to warrant anticoagulant reversal for patients requiring an urgent procedure associated with a high risk of bleeding.27 | Random sample for drug level drawn immediately prior to the procedure. | • Use of anticoagulant reversal agent. • Timing of surgery/procedure. • Use of neuraxial anesthesia. |

| Serious bleeding | Based on limited data, a DOAC drug level <50 ng/mL is unlikely to warrant anticoagulant reversal for patients with severe bleeding.27 | Random sample for drug level drawn at presentation with serious bleeding. | • Use of anticoagulant reversal agent. |

| Prior to systemic thrombolysis for acute stroke | Observational data suggest a low risk of intracranial hemorrhage among patients treated with systemic thrombolysis and a DOAC drug level <20-50 ng/mL.30-32 US and European guidelines recommend against use of systemic thrombolysis in patients who ingested a DOAC within the last 48 hours.56,57 | Random sample for drug level drawn at presentation with acute stroke. | • Use of intravenous thrombolysis or alternatives (mechanical thrombectomy). • Surgical approaches. |

| GOAL: To assess for excessively high DOAC levels (above on-therapy range) | |||

| Anticoagulant overdose | The finding of a very high DOAC drug level can confirm a diagnosis of DOAC overdose where the history is unclear. | Random sample for drug level +/- serial drug measurements. | • Reversal agents are not indicated in the absence of bleeding or surgery.58 • Serial drug level measurements can be used to calculate elimination half-life and inform when the patient is no longer at excess risk of bleeding. |

| Severe chronic kidney disease (CKD) | There is uncertainty on the appropriate use and dosing of DOACs in severe renal insufficiency. Phase III trials of DOACs for atrial fibrillation and VTE excluded patients with a creatinine clearance (CrCl) <25-30 mL/min. | Sample for drug level drawn at trough, just before the next dose is due, and after at least 5 doses to ensure drug level is checked at steady state. | • Engage in shared decision- making with the patient or caregiver on alternative options, including switching to a VKA • Plan duration of DOAC interruption for elective surgery/procedure. |

| Pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions | Apixaban and rivaroxaban are substrates of cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), and all DOACs are substrates of p-glycoprotein (p-gp). Strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 and/or p-gp can increase DOAC drug levels and may increase risk of bleeding59 (although high quality data are lacking regarding clinical outcomes). | Sample for drug level drawn at trough (just before the next dose is due) and after at least 5 doses to ensure drug level is checked at steady state.22 | • Change therapy based on drug interaction profile. |

| GOAL: To assess for excessively low DOAC levels (below on-therapy range) | |||

| Malabsorptive gastrointestinal surgery | DOACs are variably absorbed in the stomach and the proximal gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GI cancer or bariatric surgery may reduce DOAC absorption by altering GI motility, reducing stomach acidity, or disrupting the intestinal absorptive surface.40 Patients taking dabigatran or who have undergone highly malabsorptive procedures (such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) appear to be at greatest risk of malabsorption.34 | Sample for drug level drawn at peak (1-4 hours after drug ingestion), and/or at trough (just before the next dose is due).22,40 Drug level should be measured after at least 5 doses to ensure steady state is achieved. | • Engage in shared decision- making with the patient or caregiver on switching DOACs based on site of impaired absorption and remeasuring drug level, or switching to a VKA.41 |

| Pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions | Coadministration of DOACs with strong inducers of p-gp and CYP3A4 (eg, carbamazepine) can decrease DOAC drug levels and may reduce their efficacy60 (although high quality data regarding clinical outcomes are lacking). | Sample for drug level drawn at peak (1-4 hours after drug ingestion) and after at least 5 doses to ensure drug level is checked at steady state. | • Change treatment based on drug interaction profile. |

| Suspected therapeutic failure | Nonadherence to long-term anticoagulation therapy is common (impacting around 15% of patients initiated on a DOAC for atrial fibrillation)61 and associated with a higher risk of thromboembolism. Therefore, checking for adequate drug exposure may be indicated in the workup of a new thromboembolic event sustained while taking a DOAC. | Random sample for drug level drawn at the time of diagnosis of the thromboembolic event. | • Assess and optimize risk factors for nonadherence if applicable (eg, switch from twice daily drug to once daily), or switch anticoagulant (eg, to a VKA with regular INR monitoring). |

| Scenario . | Rationale . | Timing of measurement . | Potential impact on clinical decision-making . |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOAL: To assess whether a clinically significant DOAC level is likely to be present in an emergency requiring normal hemostasis | |||

| Prior to an urgent invasive procedure with high bleeding risk | Based on limited data, a DOAC drug level <30 ng/mL is unlikely to warrant anticoagulant reversal for patients requiring an urgent procedure associated with a high risk of bleeding.27 | Random sample for drug level drawn immediately prior to the procedure. | • Use of anticoagulant reversal agent. • Timing of surgery/procedure. • Use of neuraxial anesthesia. |

| Serious bleeding | Based on limited data, a DOAC drug level <50 ng/mL is unlikely to warrant anticoagulant reversal for patients with severe bleeding.27 | Random sample for drug level drawn at presentation with serious bleeding. | • Use of anticoagulant reversal agent. |

| Prior to systemic thrombolysis for acute stroke | Observational data suggest a low risk of intracranial hemorrhage among patients treated with systemic thrombolysis and a DOAC drug level <20-50 ng/mL.30-32 US and European guidelines recommend against use of systemic thrombolysis in patients who ingested a DOAC within the last 48 hours.56,57 | Random sample for drug level drawn at presentation with acute stroke. | • Use of intravenous thrombolysis or alternatives (mechanical thrombectomy). • Surgical approaches. |

| GOAL: To assess for excessively high DOAC levels (above on-therapy range) | |||

| Anticoagulant overdose | The finding of a very high DOAC drug level can confirm a diagnosis of DOAC overdose where the history is unclear. | Random sample for drug level +/- serial drug measurements. | • Reversal agents are not indicated in the absence of bleeding or surgery.58 • Serial drug level measurements can be used to calculate elimination half-life and inform when the patient is no longer at excess risk of bleeding. |

| Severe chronic kidney disease (CKD) | There is uncertainty on the appropriate use and dosing of DOACs in severe renal insufficiency. Phase III trials of DOACs for atrial fibrillation and VTE excluded patients with a creatinine clearance (CrCl) <25-30 mL/min. | Sample for drug level drawn at trough, just before the next dose is due, and after at least 5 doses to ensure drug level is checked at steady state. | • Engage in shared decision- making with the patient or caregiver on alternative options, including switching to a VKA • Plan duration of DOAC interruption for elective surgery/procedure. |

| Pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions | Apixaban and rivaroxaban are substrates of cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), and all DOACs are substrates of p-glycoprotein (p-gp). Strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 and/or p-gp can increase DOAC drug levels and may increase risk of bleeding59 (although high quality data are lacking regarding clinical outcomes). | Sample for drug level drawn at trough (just before the next dose is due) and after at least 5 doses to ensure drug level is checked at steady state.22 | • Change therapy based on drug interaction profile. |

| GOAL: To assess for excessively low DOAC levels (below on-therapy range) | |||

| Malabsorptive gastrointestinal surgery | DOACs are variably absorbed in the stomach and the proximal gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GI cancer or bariatric surgery may reduce DOAC absorption by altering GI motility, reducing stomach acidity, or disrupting the intestinal absorptive surface.40 Patients taking dabigatran or who have undergone highly malabsorptive procedures (such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) appear to be at greatest risk of malabsorption.34 | Sample for drug level drawn at peak (1-4 hours after drug ingestion), and/or at trough (just before the next dose is due).22,40 Drug level should be measured after at least 5 doses to ensure steady state is achieved. | • Engage in shared decision- making with the patient or caregiver on switching DOACs based on site of impaired absorption and remeasuring drug level, or switching to a VKA.41 |

| Pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions | Coadministration of DOACs with strong inducers of p-gp and CYP3A4 (eg, carbamazepine) can decrease DOAC drug levels and may reduce their efficacy60 (although high quality data regarding clinical outcomes are lacking). | Sample for drug level drawn at peak (1-4 hours after drug ingestion) and after at least 5 doses to ensure drug level is checked at steady state. | • Change treatment based on drug interaction profile. |

| Suspected therapeutic failure | Nonadherence to long-term anticoagulation therapy is common (impacting around 15% of patients initiated on a DOAC for atrial fibrillation)61 and associated with a higher risk of thromboembolism. Therefore, checking for adequate drug exposure may be indicated in the workup of a new thromboembolic event sustained while taking a DOAC. | Random sample for drug level drawn at the time of diagnosis of the thromboembolic event. | • Assess and optimize risk factors for nonadherence if applicable (eg, switch from twice daily drug to once daily), or switch anticoagulant (eg, to a VKA with regular INR monitoring). |

Assessing whether a clinically significant amount of DOAC is likely present in an emergency requiring normal hemostasis

The concentration threshold at which DOACs have a clinically meaningful impact on hemostasis is uncertain. Prior studies have shown that even very low DOAC levels (<10 ng/mL) have a measurable effect on thrombin generation in vitro, but the clinical significance for in vivo coagulation is uncertain.25,26 In an emergency such as serious bleeding or urgent surgery, assessing for the presence of clinically significant concentrations may be desirable to guide reversal therapy administration or surgical planning. Expert guidance from the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) endorses a cutoff of 30-50 ng/mL, below which patients are unlikely to benefit from anticoagulant reversal if they present with serious bleeding or require an urgent invasive procedure.27 However, the overall clinical utility of DOAC measurement to guide decision-making in emergencies is uncertain due to the potential for unacceptable treatment delays (eg, life-threatening intracerebral hemorrhage), the unavailability of specific DOAC assays, and challenges interpreting nonspecific (routine) coagulation tests, which are variably sensitive and specific. Very few hospital laboratories report DOAC drug levels within 30 minutes, which is the ICSH standard for test turnaround time in urgent situations.22

Given these logistical challenges and the importance of using costly reversal agents with associated thrombotic risk judiciously, the likelihood of clinically significant DOAC levels can be estimated pragmatically based on the time of last dose, drug clearance (renal/hepatic function), and the presence of interacting medications. In the ANNEXA-4 study,28 28% of patients were excluded from the efficacy analysis because they had factor Xa inhibitor levels below 75 ng/mL, which highlights the urgent need to develop reliable, accurate testing that can be used at the point of care.

In the Perioperative Anticoagulant Use for Surgery Evaluation (PAUSE) study,29 patients on apixaban and rivaroxaban undergoing scheduled surgery held their DOAC according to a prespecified schedule corresponding to 4-5 half-lives off the drug, and a subset of patients had a drug level measured immediately before surgery. Most patients had a DOAC drug level below 50 ng/mL (only 0.6% of rivaroxaban patients and 2.1% of apixaban patients exceeded this threshold), and the 30-day risk of bleeding was acceptable at around 3%. These data confirm that most patients achieve low DOAC drug levels after holding the drug for 4-5 half lives and that drug levels below 50 ng/mL enabled patients to undergo surgery with an acceptable risk of perioperative bleeding.

Several observational studies30-32 have evaluated the practice of measuring DOAC drug levels among anticoagulated patients to determine the safety of off-label systemic thrombolysis or endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. One registry evaluated a clinical algorithm where DOAC-treated patients with a drug level less than 50 ng/mL (as measured by a drug-specific anti-Xa assay) were treated with thrombolysis, and an individualized decision regarding thrombolysis was made for patients with a drug level between 50 and 100 ng/mL.32 Employing this strategy led to a low risk of intracranial hemorrhage (1 in 24 patients, or 4.2%). The median turnaround time for DOAC drug levels was 39 minutes (IQR, 35-46 minutes), and was comparable with other routine coagulation tests (eg, 39 minutes [IQR, 31-46 minutes] for INR among warfarin-treated patients) in this study.

Assessing whether DOAC levels are excessively high (above on-therapy range) or excessively low (below on-therapy range)

DOAC drug level measurement may be considered in selected stable anticoagulated patients at high risk for levels outside the typical on-therapy range due to bioaccumulation (eg, dialysis-dependent renal failure), malabsorption (eg, after major gastrointestinal surgery), extremes in body weight, or other factors (eg, drug-drug interactions with cytochrome P450 3A4 and/or p-glycoprotein inducers). Cautious interpretation of results is required, as single measurements may not reflect total anticoagulant exposure33 and multiple measurements may be affected by differences in the timing of measurement, given that drug levels change rapidly across the dosing interval; measurements should be taken after achieving steady state concentrations (ie, after at least 4-5 half lives of the drug being given at regular intervals).

Despite the aforementioned limitations, there are specific at-risk patients in whom monitoring DOAC drug levels might influence clinical decision-making. Patients who have undergone highly malabsorptive gastrointestinal surgery (including bariatric surgery, such RYGB or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch) appear to be at high risk for DOAC malabsorption. Peak DOAC drug levels below the expected on-therapy range are seen in around one-third of patients after major gastrointestinal surgery,34-36 although the clinical relevance of this finding with respect to thromboembolism risk is unknown.35 In patients with lower than expected drug levels, there may be a theoretical advantage in switching from one DOAC to another based on the drug's absorption characteristics, expected caloric intake37 (for rivaroxaban), and the type of surgery. For example, apixaban may be preferred after vertical sleeve gastrectomy or RYGB because it exhibits decreasing absorption along the length of the small bowel and ascending colon,38 as opposed to dabigatran, which is primarily absorbed in the stomach and duodenum and requires an acidic environment for absorption.39 Recent guidance from the ISTH suggests avoiding the use of DOACs for treatment or prevention of VTE within 4 weeks of bariatric surgery and to check a trough drug level if a DOAC is prescribed after this period.40 The optimal course of action for drug levels outside of the expected on-therapy range is uncertain; in these cases, the accuracy of the drug level should be confirmed by ensuring that it was measured at steady-state, that the patient was adherent to taking the drug appropriately (eg, taking rivaroxaban 20 mg with food), and that the sample for the drug level was drawn at the appropriate time (ie, just before the next dose for a trough drug level, or 1-4 hours after ingestion for a peak drug level). For drug levels deemed accurate but outside of the expected range, shared decision-making with the patient or caregiver is warranted to consider switching DOACs to one with a theoretical advantage in absorption for the specific type of surgery or to switching to a vitamin K antagonist (VKA).41

Data are less clear on the utility of measuring drug levels to assess for bioaccumulation (ie, for patients with advanced renal failure, with extremely low body weight, or with pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions that might theoretically increase DOAC exposure). Taking renal failure as an example, DOACs are cleared from the circulation by the kidney to a varying degree: 80% for dabigatran, 50% for edoxaban, 36% for rivaroxaban, and 27% for apixaban.42 Rivaroxaban is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients with atrial fibrillation and advanced kidney disease (CrCl <15 mL/min or hemodialysis dependent) where the 15 mg daily dose is expected to result in serum concentrations similar to those observed in the ROCKET AF study. Apixaban is FDA-approved for patients with atrial fibrillation or VTE and advanced kidney disease. The recommended dose of apixaban for atrial fibrillation in advanced kidney disease varies between guidelines, with some recommending standard doses of apixaban (5 mg twice daily)43,44 and others recommending dose reduction (2.5 mg twice daily).45 FDA labeling for apixaban and rivaroxaban in advanced kidney disease is based on limited pharmacokinetic and observational data,46-48 and, in the absence of adequately powered randomized trials, there remains considerable uncertainty on their safety and efficacy compared with VKAs in this population.49 Although measuring drug levels could theoretically identify patients with drug accumulation,50 prospective studies with a clinical endpoint are needed to evaluate this strategy in practice before it can be routinely recommended.

CLINICAL CASE RESOLUTION

Case 1. This 51-year-old man with recurrent VTE requires urgent surgery within 24 hours of his last dose of apixaban. We acknowledge that preoperative treatment with off-label prothrombin complex concentrate [PCC] or andexanet alfa51 can be considered; however, treatment is costly and is associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism (4%-8% short term risk of thromboembolism for PCC52-54 and up to 10% risk for andexanet alfa55). His apixaban drug level, drawn at least 6 hours before surgery, is exactly at the ISTH threshold of clinical significance for hemostatic impairment. In this case, we decided against prescribing an anticoagulant reversal drug. The patient proceeded to surgery under general anesthesia, which was uncomplicated with minimal blood loss. LMWH thromboprophylaxis was started on POD1, and we restarted apixaban 5 mg twice a day on POD2 after his diet was advanced.

Case 2. This 55-year-old woman has newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation (CHADS2 score of 4) 1 year after an RYGB. We engaged in shared decision-making with the patient, which revealed that she preferred the convenience of a DOAC over warfarin because of her poor mobility. She acknowledged the uncertainty about DOAC absorption and pharmacokinetics after bariatric surgery. We prescribed apixaban 5 mg twice a day on the basis of its primary absorption site, and measured a peak drug level 5 days later, which was 131 ng/mL (expected on-therapy range for atrial fibrillation 91-321 ng/mL at steady state). She continued taking apixaban without complication.

Acknowledgment

Deborah Siegal is supported by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Anticoagulant Management of Cardiovascular Disease.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Siraj Mithoowani: no competing financial interests to declare.

Deborah Siegal has received honoraria paid indirectly to her research institute from Astra Zeneca, BMS-Pfizer, Roche, and Servier for work unrelated to the content of this manuscript.

Off-label drug use

Siraj Mithoowani: Nothing to disclose.

Deborah Siegal: Nothing to disclose.