Learning Objectives

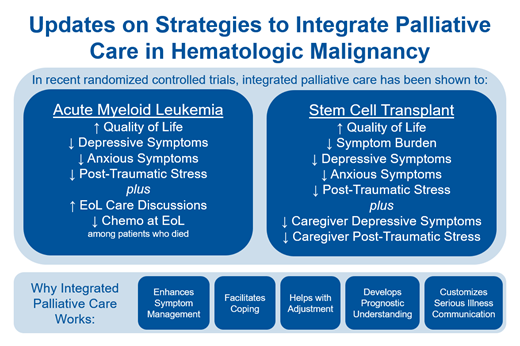

Review recent studies that have characterized the benefits of integrated palliative care in hematologic malignancies

Explain what features of integrated palliative care lead to improved outcomes in hematologic malignancies

CLINICAL CASE

A 62-year-old man is diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Molecular genetic testing reveals an NPM1 mutation without FLT3 mutation. He undergoes induction chemotherapy with cytarabine/daunorubicin with a complete response, followed by consolidation with high-dose cytarabine, but has a persisting NPM1 mutation by quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing. Ultimately, a matched unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is offered with curative intent. He is admitted to the hospital for conditioning chemotherapy with busulfan/cyclophosphamide. Palliative care (PC) consultation is offered to the patient. Do patients undergoing HSCT benefit from PC during their initial transplant hospitalization?

PC in hematologic malignancies

The integration of PC in hematologic malignancies has lagged behind solid oncology for many reasons, including prognostic uncertainty, the use of intense treatments that may result in a cure, misperceptions of PC as end-of-life (EoL) care, cultural paradigms in hematologic oncology, and limited evidence for its use in this patient population.1 More patients with hematologic malignancies are being referred to PC, but expert consensus remains that only a small minority of patients and families who could benefit from PC are referred early, if at all, in their illness course.2 Hematologic malignancies result in substantial physical and psychological suffering for patients and families, often starting at diagnosis. With this, patients and families may miss out on many benefits of PC if referred too late.3

Historically, research has focused on the EoL-specific benefits of PC in hematologic malignancies, including improved hospice utilization, more likely out-of-hospital death, and decreased health care utilization.4 Although these are important findings, we have only recently characterized the upstream benefits of PC in this population. Since the publication of the last evidence-based minireview on PC in 2015,5 the literature base has grown significantly and now includes multiple randomized trials confirming the benefits of integrated PC in hematologic malignancy. Accordingly, the 2024 update of the American Society for Clinical Oncology guidelines now recommends specialist PC for all patients with hematologic malignancies.6

Integrated PC makes a difference in AML and HSCT

Acute myeloid leukemia

The diagnosis of AML and the initiation of high-intensity chemotherapy is a uniquely challenging experience. Patients experience intense physical symptoms and psychological distress through an urgent and prolonged hospitalization.7 Recognizing this, a multisite randomized trial enrolled 160 patients, comparing the effect of inpatient PC with the usual care on quality of life (QoL) and other patient-reported outcomes in high-risk AML (Table 1).8 Patients receiving PC saw a PC clinician an average of 2.2 times per week during their induction hospitalization. Compared to the usual care, those receiving PC reported better QoL, as well as lower depressive, anxious, and post-traumatic stress symptoms at 2 weeks. Among those who died, those receiving PC were more likely to discuss their EoL care preferences and were less likely to receive chemotherapy in the last month of life. These findings demonstrate that PC confers significant benefits related to QoL and important EoL care measures when patients are referred during induction chemotherapy.

Patient-reported outcomes in studies comparing integrated PC with usual care in patients with hematologic malignancies

| Study . | Design . | N . | Hematologic malignancy . | Outcome . | Time . | Scales . | P . | Conclusions . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El-Jawahri et al8 | RCT comparing integrated PC to usual care in patients undergoing intensive chemotherapy for AML | 160 | AML | Standardized mean difference between scores | 2 wk | FACT-L HADS-A HADS-D PHQ-9 ESAS PCL | .04 .02 .02 .04 .12 .01 | Significant difference in change of scores over 12 weeks for multiple scales except ESAS, favoring integrated PC group. |

| El-Jawahri et al10,11 | RCT comparing integrated PC to usual care in patients undergoing HSCT (single site) | 160 | HSCT | Standardized mean difference between scores | 2 wk 3 mo 6 mo | Patients FACT-BMT FACT-F HADS-A HADS-D PHQ-9 ESAS Caregivers CGO-QOL CGO-QOL-C CGO-QOL-AF HADS-A HADS-D PHQ9 FACT-BMT FACT-F HADS-A HADS-D PHQ-9 ESAS PTSDC-C FACT-BMT FACT-F HADS-A HADS-D PHQ-9 PCL | .02 .04 <.001 .008 .10 .02 .24 .02 .02 .95 .03 .99 .048 .20 .13 .002 .002 .21 .002 .346 .957 .267 .024 .027 .013 | Significant difference in change of patient scores over 2 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months for multiple scales, favoring early PC group. Significant difference in change of caregiver scores over 2 weeks for CGO-QOL coping and administrative/financial subscales and HADS-D, favoring integrated PC group. |

| El-Jawahri et al12 | RCT comparing early PC to usual care in patients undergoing HSCT (multisite) | 360 | HSCT | Standardized mean difference between scores | 2 wk | FACT-BMT FACT-F HADS-A HADS-D PCL ESAS | <.001 .014 NS .041 .022 .018 | Significant difference in change of patient scores over 2 weeks, favoring integrated PC group. |

| Study . | Design . | N . | Hematologic malignancy . | Outcome . | Time . | Scales . | P . | Conclusions . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El-Jawahri et al8 | RCT comparing integrated PC to usual care in patients undergoing intensive chemotherapy for AML | 160 | AML | Standardized mean difference between scores | 2 wk | FACT-L HADS-A HADS-D PHQ-9 ESAS PCL | .04 .02 .02 .04 .12 .01 | Significant difference in change of scores over 12 weeks for multiple scales except ESAS, favoring integrated PC group. |

| El-Jawahri et al10,11 | RCT comparing integrated PC to usual care in patients undergoing HSCT (single site) | 160 | HSCT | Standardized mean difference between scores | 2 wk 3 mo 6 mo | Patients FACT-BMT FACT-F HADS-A HADS-D PHQ-9 ESAS Caregivers CGO-QOL CGO-QOL-C CGO-QOL-AF HADS-A HADS-D PHQ9 FACT-BMT FACT-F HADS-A HADS-D PHQ-9 ESAS PTSDC-C FACT-BMT FACT-F HADS-A HADS-D PHQ-9 PCL | .02 .04 <.001 .008 .10 .02 .24 .02 .02 .95 .03 .99 .048 .20 .13 .002 .002 .21 .002 .346 .957 .267 .024 .027 .013 | Significant difference in change of patient scores over 2 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months for multiple scales, favoring early PC group. Significant difference in change of caregiver scores over 2 weeks for CGO-QOL coping and administrative/financial subscales and HADS-D, favoring integrated PC group. |

| El-Jawahri et al12 | RCT comparing early PC to usual care in patients undergoing HSCT (multisite) | 360 | HSCT | Standardized mean difference between scores | 2 wk | FACT-BMT FACT-F HADS-A HADS-D PCL ESAS | <.001 .014 NS .041 .022 .018 | Significant difference in change of patient scores over 2 weeks, favoring integrated PC group. |

Bold typeface indicates significant differences found between intervention and control groups.

CGO-QOL, CareGiver Oncology Quality of Life Questionnaire; CGO-QOL-AF, CareGiver Oncology Quality of Life Questionnaire Administrative and Financial subscale; CGO-QOL-C, CareGiver Oncology Quality of Life Questionnaire Coping subscale; ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; FACT-L, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Leukemia; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Anxiety subscale; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Depression subscale; PCL, Post-Traumatic Distress Checklist—Civilian; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant

Undergoing HSCT is similarly difficult due to the significant symptom burden, psychological distress, isolation related to conditioning chemotherapy, prolonged immune compromise, and posttransplant complications.9 A similarly constructed single-center randomized trial compared in-hospital PC with the usual care for 160 patients undergoing autologous or allogeneic transplant (Table 1).10 Patients receiving PC had a better QoL at 2 weeks compared to the usual care, with fewer issues regarding symptom burden, depression, and anxiety. Despite the PC intervention being limited to the index transplant hospitalization, the observed effects on QoL and depression persisted at 3 months, and effects on depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms persisted at 6 months.11 Caregiver outcomes were similarly tracked, and PC was associated with decreased depressive symptoms and improved QoL related to coping and administrative/financial domains for caregivers. These data suggest that even short-term exposure to PC during a period of intense physical and emotional distress can durably improve QoL. These findings have recently been replicated in a multisite randomized trial among 360 patients treated at 3 major transplant centers (Table 1).12

Why integrated PC works in hematologic malignancies

Historically, the observed benefit of integrated PC was attributed to improved symptom control and additional contact with clinicians.13 With further study we have recognized other important mediators of improved QoL, especially in patients with hematologic malignancies. Interdisciplinary PC teams help patients and families adjust to new diagnoses and progressive illness, facilitate an understanding and awareness of prognosis, and provide patient- and family-customized serious illness communication.14 Of particular interest in this patient population, PC actively facilitates improved patient and family coping.15,16 In the above AML trial, mediation analysis found that intervention effects on coping may account for as much as 78% of the effect of PC on overall QoL and significant proportions of the effect on depression and anxiety symptoms.17 Crucially, studies of integrated PC have focused on interventions that rely solely on clinician visits. We anticipate that patients and families also benefit from the involvement of other members of the PC interdisciplinary team, including specialist chaplains, social workers, and nurses.18

Future research directions

These studies suggest an expanded role for integrated PC in hematologic malignancies. Unfortunately, barriers to expanded PC access and delivery persist. One of the most significant challenges facing PC as a discipline is the lack of clear referral criteria in a consultative model that depends on timely and appropriate referral from other disciplines.19 Previously employed models of PC referral have been criticized as being overly “sensitive” (ie, occurs in the absence of unmet need or before needs develop) or “specific” (occurs too late or when unmet needs are extreme).2 This has led to calls to deploy new technologies (including machine-learning mortality prediction and natural language-processing algorithms and provider “nudge” notifications in the medical record) to deliver more precise PC, in which the patient's unmet PC need(s) are identified as early as possible, and their care model routes them to the most appropriate interdisciplinary PC professional to address that particular need.20-23

Although PC is more broadly available now than earlier in its history, the workforce is small and access issues remain.24 One of the most significant barriers to improving PC availability is a limited workforce relative to clinical demand.18 In order to sustainably deliver PC to patients with hematologic malignancies, we need to identify the “minimum effective dose” necessary to improve outcomes. To better understand the dosing of PC in AML and explore alternative care delivery models, a multisite trial is underway to determine whether a hematologist-delivered intervention is noninferior to specialist PC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT05237258). Studies to this point have focused exclusively on inpatient PC delivery. It is important that future studies explore the efficacy and feasibility of outpatient and mixed PC delivery models in this population.

Last, PC expertise continues to cluster around academic centers and large accountable care organizations, with significantly less availability in smaller community-based centers.24 Efforts must be undertaken to ensure that patients have access to high-quality PC regardless of where they live and receive their cancer treatment. As such, we must develop scalable and pragmatic PC interventions that translate across care settings.

Conclusion

Recent years have yielded exciting data about the benefit of integrated PC in AML and HSCT, reinforcing its critical importance in hematologic malignancy care. Additional studies to better characterize PC's effect in other hematologic malignancies, understand the minimum effective dose of PC in these populations, and develop scalable PC interventions are critical.

Recommendations

In patients with AML receiving high-intensity induction chemotherapy, we recommend integrated specialist PC (grade 1B).

In patients undergoing HSCT, we recommend integrated specialist PC (grade 1B).

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Wil L. Santivasi: no competing financial interests to declare.

Thomas W. Leblanc: consultancy: AbbVie, Agilix, Agios/Servier, Apellis, Astellas, Beigene, BlueNote, Bristol Myers Squibb/ Celgene, Genentech, Gilead, GSK, Lilly, Meter Health, Novartis, Pfizer; honoraria: AbbVie, Agios, Astellas, Bristol Myers Squibb/ Celgene, GSK, Incyte, Rigel; equity interest: Dosentrx, ThymeCare; royalties: UpToDate; research funding: AbbVie, American Cancer Society, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Deverra Therapeutics, Duke University, GSK, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, National Institute of Nursing Research/National Institutes of Health, Seattle Genetics.

Off-label drug use

Wil L. Santivasi: None.

Thomas W. Leblanc: None.