Abstract

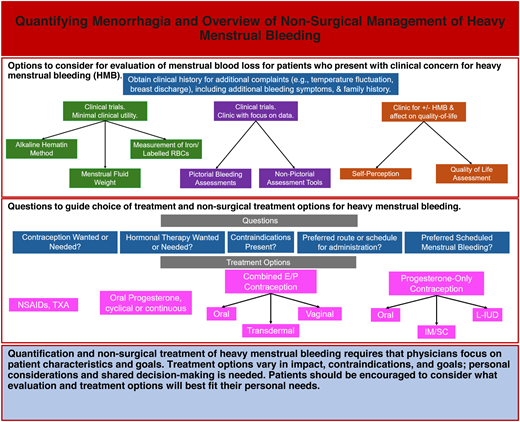

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is a common problem, presenting in 1 in 5 females. The quantification of menstrual blood loss and the subsequent treatment of HMB are both nuanced tasks that require the physician to consider the patient perspective. The individualization of care and transition to methods that fit each individual patient are critical to building a successful relationship with the patient to facilitate follow-up care and evaluation of response to treatment. In this review we outline various methods of quantification of menstrual blood loss, including considerations of accuracy and practicality. These methods, all of which have the potential for clinical benefit, vary from pictorial assessment charts to the gold standard alkaline hematin method to asking the patient about their average amount of blood loss and how it affects their quality of life. Next, we outline nonsurgical treatments for HMB, including hormonal and nonhormonal options, and consider the potential for success, as well as treatment considerations and contraindications. Overall, options for the evaluation and nonsurgical management of menstrual blood loss and HMB are presented along with quality-of-life considerations.

Learning Objectives

Describe and compare the clinical tools used to quantify HMB to optimize patient care and data collection

Describe the characteristics, benefits, and contraindications of hormonal and nonhormonal menstrual management options

CLINICAL CASE

A 16-year-old girl (she/her) presents with her mother to discuss heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB). The mother is very concerned at the number of tampons used, but the patient argues that she did not want this visit. The patient reports menarche at age 13 with regular monthly cycles that last 7 to 8 days. She describes her bleeding as “normal,” saying “It's fine.” Mom clarifies that her daughter has had to come home from school several times after bleeding into her clothes. Their doctor has diagnosed iron deficiency without anemia. You consider how to determine whether this patient has HMB.

Quantification of HMB

The quantification of menstrual blood loss (MBL) requires consideration of both the accuracy and practicality of the measurement tool. HMB is historically defined as MBL of more than 80 mL and/or bleeding for over 7 days per menstrual cycle.1 However, multiple organizations have transitioned to a more comprehensive definition of excessive MBL that interferes with a female's physical, social, or maternal quality of life (QOL).

The most quantitatively accurate assessment of MBL is the alkaline hematin (AH) method, a chemical measurement of blood from collected cotton menstrual products.2 Menstrual fluid weight and the measurement of iron/ labeled red blood cells are additional accurate measurements, but this test is quite laborious. Given the difficulty with directly measuring menstrual blood, a variety of tools have been developed to collect these data more practically. These authors advocate for considering provider goals (eg, exact MBL vs effect on QOL) as well as the environment (eg, clinical trial, clinic) when choosing a method of quantification (Table 1).

Review of methods to quantify HMB

| Goals . | MLB assessment method . | Advantages . | Disadvantages . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good for clinical trials focused specifically and strictly on volume of menstrual blood Minimal clinical utility | AH method | • “Gold standard” | • Collection of pads is laborious • Breakthrough bleeding is lost |

| Menstrual fluid weight | • Simple | • Collection of pads is laborious • Fluid evaporation can affect measurement | |

| Measurement of iron/ labeled red blood cells | • Great accuracy | • Technically challenging | |

| Good for clinic patients with focus on numbers/data Use in clinical trials for estimated volume assessment | Pictorial bleeding assessments | • Simple and easy to learn • Semiquantitative | • Validated for specific products • Participant assessment of soiling |

| Nonpictorial assessment tools | • Variability | • Poorly validated | |

| Good for clinical assessment of presence or absence of HMB and effect on QOL Often secondary outcomes for clinical trials | QOL assessment | • Insight into effect of menstrual bleeding | • Lack of volume • Individual variation |

| Self-perception | • Simple • Helpful for clinical impact | • Lack of volume of MBL assessment • Individual variation |

| Goals . | MLB assessment method . | Advantages . | Disadvantages . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good for clinical trials focused specifically and strictly on volume of menstrual blood Minimal clinical utility | AH method | • “Gold standard” | • Collection of pads is laborious • Breakthrough bleeding is lost |

| Menstrual fluid weight | • Simple | • Collection of pads is laborious • Fluid evaporation can affect measurement | |

| Measurement of iron/ labeled red blood cells | • Great accuracy | • Technically challenging | |

| Good for clinic patients with focus on numbers/data Use in clinical trials for estimated volume assessment | Pictorial bleeding assessments | • Simple and easy to learn • Semiquantitative | • Validated for specific products • Participant assessment of soiling |

| Nonpictorial assessment tools | • Variability | • Poorly validated | |

| Good for clinical assessment of presence or absence of HMB and effect on QOL Often secondary outcomes for clinical trials | QOL assessment | • Insight into effect of menstrual bleeding | • Lack of volume • Individual variation |

| Self-perception | • Simple • Helpful for clinical impact | • Lack of volume of MBL assessment • Individual variation |

Pictorial menstrual quantification tools

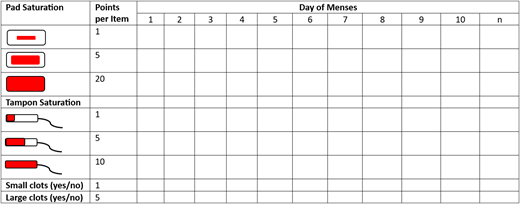

Pictorial assessments quantitatively assess MBL and rely on patients to record the number of menstrual products used each day and the degree to which each product is soiled; observations are then compared to a visual scoring system. These tools rely on the use of menstrual pads and tampons and thus are limited by the use of modern products that are more variable (DIVA cup, menstrual discs, period underwear, etc); a recent assessment of the red blood cell volume capacity of menstrual products emphasizes the criticality of a careful review of products when obtaining a menstrual history.3

The pictorial bleeding assessment chart (PBAC) (Figure 1) is a prospective tool first evaluated in comparison with the AH method. Numerous follow-up studies have investigated its potential to identify HMB. In the original study both the patients and gynecologist completed the PBAC; a PBAC score of more than 100 correlated with HMB (>80 mL MBL).4 In various studies the sensitivity (58%-99%) and specificity (7.5%-89%) of a PBAC score of more than 100 have demonstrated variability, as have assessments of alternative PBAC cutoff values (Table 2). Furthermore, the PBAC has been shown to distinguish the degree of MBL in both adult and adolescent females (Table 3).5,6 Overall, this assessment tool can be used to identify females with HMB and semiquantify blood loss; however, interindividual variations in PBAC scores have been noted. Variability is likely multifactorial given that patients' subjective assessment of degrees of soiling and newer menstrual products are both contributing. The PBAC was validated with specific products, but modern products have improved absorption with significant volume and visual variation. A recent reassessment of the scoring system provides a more nuanced measurement using modern products and should be considered to improve accuracy for clinical or research work.7

PBAC—each pad and/or tampon used throughout a menstrual cycle is counted with an assessment of saturation. Points are tallied at the end of the cycle. Additionally, 1 point is added for small (1 cm) clots each day and 5 points are added for large (>2 cm) clots each day.

PBAC—each pad and/or tampon used throughout a menstrual cycle is counted with an assessment of saturation. Points are tallied at the end of the cycle. Additionally, 1 point is added for small (1 cm) clots each day and 5 points are added for large (>2 cm) clots each day.

Assorted studies evaluating PBAC for the identification of HMB

| . | Number of females . | Number of cycles . | PBAC cutoff . | Comparison . | Sensitivity (%) . | Specificity (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higham et al4 | 28 | 55 | >100 | >80 mL via AH | 86 | 89 |

| Janssen et al41 | 288 | 489 | >185 | 62 | 96 | |

| 90-300 | 98-19 | 52-100 | ||||

| Reid et al42 | 103 | 103 | >100 | 97 | 7.5 | |

| Zakherah et al43 | 197 | 241 | >100 | 99 | 39 | |

| >150 | 83 | 77 | ||||

| Hald and Lieng5 | 429 | 1049 | >160 | Subjective assessment | 78.5 | 75.8 |

| 75-450 | 96-20 | 39-99 |

| . | Number of females . | Number of cycles . | PBAC cutoff . | Comparison . | Sensitivity (%) . | Specificity (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higham et al4 | 28 | 55 | >100 | >80 mL via AH | 86 | 89 |

| Janssen et al41 | 288 | 489 | >185 | 62 | 96 | |

| 90-300 | 98-19 | 52-100 | ||||

| Reid et al42 | 103 | 103 | >100 | 97 | 7.5 | |

| Zakherah et al43 | 197 | 241 | >100 | 99 | 39 | |

| >150 | 83 | 77 | ||||

| Hald and Lieng5 | 429 | 1049 | >160 | Subjective assessment | 78.5 | 75.8 |

| 75-450 | 96-20 | 39-99 |

Studies demonstrating PBAC quantification of subjective light, normal, and heavy menstrual bleeding

| . | Number of females . | Value reported . | PBAC “light” . | PBAC “normal” . | PBAC “heavy” . | Specificity (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanchez et al6 | 73 | Mean | 44 | 136 | 362 | 89 |

| Hald and Lieng5 | 429 | Median | 45 | 116 | 255 | 52 |

The menstrual pictogram is an alternative pictorial assessment of MBL, which distinguishes between daytime and nighttime bleeding and has been validated in comparison to both the AH method and the self-assessment of menstrual bleeding with a sensitivity of 82% to 95% and a specificity of 88% to 94%.8 Additional nonvalidities pictorial assessment tools, as well as pad and tampon counts, have been investigated while also considering menstrual blood clots and breakthrough bleeding, with variable results.

Nonpictorial tools

Tools that aim to assess the degree of HMB and additional concerning symptoms have also been investigated and demonstrated variability utility. These tools take advantage of the variety of signs and symptoms that have been associated with HMB (eg, bleeding for more than 7 days, saturating a tampon in less than 2 hours).

The MBL tool includes 2 questionnaires: one asks general questions about menstrual characteristics, and the second asks for duration of menses and number and size of pads or tampons used on heavy bleeding days. The MBL score quantifies blood loss based on the data from the second questionnaire. The tool has shown correlation with a history of anemia, hormonal contraceptive use, and various hematologic parameters, including iron deficiency.9

The Philipp tool was designed as a screening tool with maximized sensitivity and positive predictive value for the identification of patients with HMB at risk of a bleeding disorder. It includes 8 questions in 4 categories (Table 4). While this tool does not provide a clear quantitative assessment of menses, it can be used to identify persons who warrant evaluation for hemostatic disorders, with sensitivity ranging from 89% in adults to 62% in adolescents.10

Questionnaire-based assessments of HMB

| . | Questions . |

|---|---|

| Philipp et al10 | • How many days did your period usually last, from the time bleeding began until it completely stopped? • How often did you experience a sensation of “flooding” or “gushing” during your period? • During your period did you ever have bleeding where you would bleed through a tampon or napkin in 2 hours or less? • Have you ever been treated for anemia? • Has anyone in your family ever been diagnosed with a bleeding disorder? • Have you ever had a tooth extracted or had dental surgery? If yes, any bleeding concerns? • Have you ever had surgery other than dental surgery? If yes, any bleeding concerns? • Have you ever been pregnant? If yes, any bleeding concerns? |

| Matteson et al12 (selected questions) | • During the past month, how would you describe your periods? • On your heaviest day of bleeding during the past month, how many high-absorbency sanitary products did you soak (either completely or almost completely)? • During the past month, how many times have you had an episode of bleeding that soaked through your “outer” clothes (pants, skirt, dress)? • During the past month, how many times did you pass blood clots (clumps of blood)? • Please fill in the following statement about pain related to your period. During the past month, my period was associated with . . . • During the past month, how many days do think your work at your job suffered because you were bleeding? • During the past month, how many days did you avoid family activities (grocery shopping, household chores) when you thought you would be bleeding? • During the past month, on how many days did you plan your activities (work, social, or family) based on whether or not there was a bathroom nearby? • During the past month, on how many days did you choose what to wear based on whether or not you were bleeding? • On a scale of 0-10, with 0 being no concern at all and 10 being extremely concerned, please rate your overall concern about bleeding staining your clothes. |

| Toxqui et al9 | • Self-judgment: Do you believe that you have an excessive menstrual flow? • Lasting days: • Does your menses last for more than 7 days? • Total number of days in a single menstrual period: • Total pad counts per single menstrual period: • Do you use more than 20 pads during a single menstrual period? • Total pad counts in a single menstrual period: • Number of sanitary products changed per day: • Do you need to change pads or tampons more frequently than every 3 hours? • Number of pads on the day with the heaviest menstrual flow: • Leaking of menstrual blood: Do you experience frequent episodes of accidental soiling of your clothing or bedsheets? • Presence of coagulated menstrual blood: Do you pass blood clots that are larger than 1 inch in diameter? |

| . | Questions . |

|---|---|

| Philipp et al10 | • How many days did your period usually last, from the time bleeding began until it completely stopped? • How often did you experience a sensation of “flooding” or “gushing” during your period? • During your period did you ever have bleeding where you would bleed through a tampon or napkin in 2 hours or less? • Have you ever been treated for anemia? • Has anyone in your family ever been diagnosed with a bleeding disorder? • Have you ever had a tooth extracted or had dental surgery? If yes, any bleeding concerns? • Have you ever had surgery other than dental surgery? If yes, any bleeding concerns? • Have you ever been pregnant? If yes, any bleeding concerns? |

| Matteson et al12 (selected questions) | • During the past month, how would you describe your periods? • On your heaviest day of bleeding during the past month, how many high-absorbency sanitary products did you soak (either completely or almost completely)? • During the past month, how many times have you had an episode of bleeding that soaked through your “outer” clothes (pants, skirt, dress)? • During the past month, how many times did you pass blood clots (clumps of blood)? • Please fill in the following statement about pain related to your period. During the past month, my period was associated with . . . • During the past month, how many days do think your work at your job suffered because you were bleeding? • During the past month, how many days did you avoid family activities (grocery shopping, household chores) when you thought you would be bleeding? • During the past month, on how many days did you plan your activities (work, social, or family) based on whether or not there was a bathroom nearby? • During the past month, on how many days did you choose what to wear based on whether or not you were bleeding? • On a scale of 0-10, with 0 being no concern at all and 10 being extremely concerned, please rate your overall concern about bleeding staining your clothes. |

| Toxqui et al9 | • Self-judgment: Do you believe that you have an excessive menstrual flow? • Lasting days: • Does your menses last for more than 7 days? • Total number of days in a single menstrual period: • Total pad counts per single menstrual period: • Do you use more than 20 pads during a single menstrual period? • Total pad counts in a single menstrual period: • Number of sanitary products changed per day: • Do you need to change pads or tampons more frequently than every 3 hours? • Number of pads on the day with the heaviest menstrual flow: • Leaking of menstrual blood: Do you experience frequent episodes of accidental soiling of your clothing or bedsheets? • Presence of coagulated menstrual blood: Do you pass blood clots that are larger than 1 inch in diameter? |

QOL and self-reported bleeding

Clinicians should consider the perception of bleeding and the impact of bleeding on QOL. A multidimensional, menstrual-specific, validated questionnaire that includes both bleeding and QOL assessment is preferred to account for the physical, psychological, and financial effects of HMB. QOL tools play an important part in clinical assessment and can be an important clinical trial end point.

Multiple QOL tools have been used to evaluate HMB.11 For this review the menstrual bleeding questionnaire (MBQ) is discussed. The MBQ includes the subjective assessment of heaviness of bleeding, bleeding pattern, pain and impact of symptoms, and social and behavioral effects (Table 3). The MBQ, scored from 0 to 75, demonstrated discrimination with minimal recall bias between adult women with no menstrual problems (mean, 10.6) and those with HMB (mean, 30.8).12 The adolescent MBQ demonstrates excellent discrimination when a score of 30 or higher is used as a cutoff.13 The MBQ/adolescent MBQ and other QOL tools have the potential to provide insight into the effect of HMB without the need for quantification of pads/tampons or other prospective assessments.

Self-reporting of MBL should also be considered. Although there is inherent concern with self-reported symptoms and poor correlation with objective measurements has been noted, 1 recent prospective study of 301 premenopausal females asked, “Do you believe that you have an excessive menstrual flow?” (Table 4). This self-perception question was the only significant predictor of HMB with associated iron deficiency anemia in multivariate analysis.14

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient agrees that her periods last 7 to 8 days, but she cannot firmly quantify the number of tampons used. She states that she can make it through 1 class (55 minutes) but not 2 before having to change her tampon on her 5 heavy days and on reflection uses about 4 tampons per school day. She goes home once every other month due to breakthrough bleeding, which is frustrating because it forces her to miss after-school activities. You conclude that while a PBAC cannot be calculated, her school day tampon use on heavy days reflects a score of 100 alone. Combined with the effect on her QOL due to missed school and activities, you elect to discuss details of menstrual control options.

Nonsurgical treatment of HMB

The treatment of HMB requires individualization with an understanding of the mechanism of action, potential benefits, and contraindications of treatment options (Table 5). It is important to discuss medical history and additional goals beyond a reduction in menstrual bleeding, as well as personal preferences and expectations of successfully maintaining the treatment schedule. These authors recommend a systematic series of questions that assesses both medical and social considerations (Figure 2). Generally, a treatment option should be monitored for 3 to 6 months in the absence of concerning side effects or worsening bleeding as many treatments, especially hormonal management, require this time to demonstrate full efficacy. This multifaceted discussion is critical as studies demonstrate minimal to no QOL changes between treatment options.15,16 Further, qualitative, interview-style research demonstrates the importance of individualization on treatment preference as patients consider HMB and its impact on fertility, method familiarity, and ability to control the method start and stop times as important contributors to the selection of a product.17 Hemostatic testing for bleeding disorders should be considered at presentation, prior to the initiation of estrogen therapy, and after the resolution of physiological stress (eg, improvement of bleeding, resolution of iron deficiency).

Treatment of HMB algorithm—step-by-step questions to guide providers and patients through the process of choosing a menstrual management option. H/O, history of; HTN, hypertension; IM, intramuscular; SC, subcutaneous.

Treatment of HMB algorithm—step-by-step questions to guide providers and patients through the process of choosing a menstrual management option. H/O, history of; HTN, hypertension; IM, intramuscular; SC, subcutaneous.

Treatment options for HMB

| . | Agent . | Examples . | Mechanism . | Contraception . | Dosing . | Contraindications . | Amenorrhea rate . | Additional information . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonhormonal | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories | Ibuprofen, naproxen, mefenamic acid | Cyclo-oxygenase inhibition, decreased prostaglandins | No | • Varies | Allergic reaction, gastrointestinal disease, renal disease, some bleeding disorders | N/A | May benefit dysmenorrhea. |

| TXA | ——- | Reversibly blocks lysine-binding sites on plasminogen, slows fibrin degradation, stabilized clots | No | • 1300 mg 3 times daily for 5 days | Thromboembolic disease, defective color vision | N/A | ||

| Combined hormonal | COCs | Multiple | Suppresses endogenous estrogen production, thins uterine lining | Yes | • Varies, daily administration | Thromboembolic disease, migraine with aura, hypertension, breast cancer, liver disease, smokers >35 y of age | 79-88% at 12 cycles | Can take for extended duration. May benefit dysmenorrhea and/or acne. |

| Transdermal contraceptive patch | Xulane | Yes | • 120 µg levonorgestrel and 30 µg EE • 150 µg norelgestromin and 35 µg EE • Weekly patch change | No specific data; good with prolonged use | May benefit dysmenorrhea and/or acne. Not recommended for body mass index >30 or weight >198 lbs due to decreased efficacy. | |||

| Vaginal contraceptive ring | Nuvaring | Yes | • 120 µg etonogestrel and 15 µg EE (1 cycle) • 150 µg segesterone acetate and 13 µg EE (reuse for 13 cycles) • Monthly maintenance | Up to 89% at 6 mo | Easy extended use. May benefit dysmenorrhea and/or acne. May have less nausea compared to oral and transdermal. | |||

| Progesterone-only hormonal | Cyclic oral progesterone | Medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethindrone acetate | Thins uterine lining, decreased angiogenesis | No | • MPA 5-20 mg/d • NA 5-15 mg/d during luteal phase (cycle days 15-19 through 23-26) | Breast cancer, liver disease | N/A | |

| Continuous oral progesterone | Medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethindrone acetate | Thins uterine lining, may suppress endogenous estrogen production | No | • MPA 5-20 mg/d in 1-3 divided doses • NETA 5-15 mg/d in 1-3 divided doses | Up to 76% at 2 y | |||

| POPS | Norethindrone, Slynd, Opill | Thins uterine lining, may suppress endogenous estrogen production | Yes | • 35 µg norethindrone daily • 4 mg drosperinone daily • 75 µg norgestrel daily | No specific data; low for lower-dose pills | |||

| Progesterone-only injectable contraceptive | Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate | Thins uterine lining, suppresses endogenous estrogen production | Yes | • 150 mg intramuscular MPA every 3 mo • 104 mg SC MPA every 3 mo | 50% at 1 y; 68-71% at 2 y | Significant side effects of weight gain and potential exacerbation of mood symptoms. Reversible bone density loss limits duration of therapy. Intermediate thrombosis risk. | ||

| Progesterone-only contraceptive implant | Nexplanon | Thins uterine lining, may suppress endogenous estrogen production | Yes | • 68 mg etonogestrel | 22% | |||

| Progesterone-only IUS | Levonorgestrel | Thins uterine lining | Yes | • 20 µg/d • 17.5 µg/d • 14 µg/d | 50% at 1 y; 60% at 2 y | Contraindicated for uterine anomalies, active PID or active lower genital tract STI. |

| . | Agent . | Examples . | Mechanism . | Contraception . | Dosing . | Contraindications . | Amenorrhea rate . | Additional information . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonhormonal | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories | Ibuprofen, naproxen, mefenamic acid | Cyclo-oxygenase inhibition, decreased prostaglandins | No | • Varies | Allergic reaction, gastrointestinal disease, renal disease, some bleeding disorders | N/A | May benefit dysmenorrhea. |

| TXA | ——- | Reversibly blocks lysine-binding sites on plasminogen, slows fibrin degradation, stabilized clots | No | • 1300 mg 3 times daily for 5 days | Thromboembolic disease, defective color vision | N/A | ||

| Combined hormonal | COCs | Multiple | Suppresses endogenous estrogen production, thins uterine lining | Yes | • Varies, daily administration | Thromboembolic disease, migraine with aura, hypertension, breast cancer, liver disease, smokers >35 y of age | 79-88% at 12 cycles | Can take for extended duration. May benefit dysmenorrhea and/or acne. |

| Transdermal contraceptive patch | Xulane | Yes | • 120 µg levonorgestrel and 30 µg EE • 150 µg norelgestromin and 35 µg EE • Weekly patch change | No specific data; good with prolonged use | May benefit dysmenorrhea and/or acne. Not recommended for body mass index >30 or weight >198 lbs due to decreased efficacy. | |||

| Vaginal contraceptive ring | Nuvaring | Yes | • 120 µg etonogestrel and 15 µg EE (1 cycle) • 150 µg segesterone acetate and 13 µg EE (reuse for 13 cycles) • Monthly maintenance | Up to 89% at 6 mo | Easy extended use. May benefit dysmenorrhea and/or acne. May have less nausea compared to oral and transdermal. | |||

| Progesterone-only hormonal | Cyclic oral progesterone | Medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethindrone acetate | Thins uterine lining, decreased angiogenesis | No | • MPA 5-20 mg/d • NA 5-15 mg/d during luteal phase (cycle days 15-19 through 23-26) | Breast cancer, liver disease | N/A | |

| Continuous oral progesterone | Medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethindrone acetate | Thins uterine lining, may suppress endogenous estrogen production | No | • MPA 5-20 mg/d in 1-3 divided doses • NETA 5-15 mg/d in 1-3 divided doses | Up to 76% at 2 y | |||

| POPS | Norethindrone, Slynd, Opill | Thins uterine lining, may suppress endogenous estrogen production | Yes | • 35 µg norethindrone daily • 4 mg drosperinone daily • 75 µg norgestrel daily | No specific data; low for lower-dose pills | |||

| Progesterone-only injectable contraceptive | Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate | Thins uterine lining, suppresses endogenous estrogen production | Yes | • 150 mg intramuscular MPA every 3 mo • 104 mg SC MPA every 3 mo | 50% at 1 y; 68-71% at 2 y | Significant side effects of weight gain and potential exacerbation of mood symptoms. Reversible bone density loss limits duration of therapy. Intermediate thrombosis risk. | ||

| Progesterone-only contraceptive implant | Nexplanon | Thins uterine lining, may suppress endogenous estrogen production | Yes | • 68 mg etonogestrel | 22% | |||

| Progesterone-only IUS | Levonorgestrel | Thins uterine lining | Yes | • 20 µg/d • 17.5 µg/d • 14 µg/d | 50% at 1 y; 60% at 2 y | Contraindicated for uterine anomalies, active PID or active lower genital tract STI. |

EE, ethinylestradiol; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; NETA, norethisterone acetate; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; SC, subcutaneous; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are thought to reduce MBL by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase, thereby reducing prostaglandins. For maximized benefit, NSAIDs should be scheduled continuously during the heaviest days of bleeding.

A 2020 Cochrane review showed a mean decrease of 124 mL per cycle for NSAIDs when compared to placebo and similar decreases in MBL between NSAIDs and combined oral contraceptives (COCs).18 There were no significant differences between different NSAIDs, with mefenamic acid and naproxen being the most commonly studied medications.19 However, NSAIDs were outperformed by tranexamic acid (TXA), danazol, and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (L-IUS).

Antifibrinolytics

Antifibrinolytics reduce MBL by reversibly blocking lysine-binding sites on plasminogen, slowing the downstream degradation of fibrin and the stabilizing of clots. In 2009 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved oral TXA for the treatment of HMB.

A multicenter randomized controlled trial (mRCT) published in 2010 demonstrated a mean decrease in MBL of approximately 57 mL per cycle compared to placebo in addition to improvements in perceived menstrual flow and work limitations (P < .001).20 A 2011 mRCT compared standard TXA dosing, low-dose TXA, and placebo. Both standard and low-dose TXA showed decreased MBL compared to placebo (62 mL/cycle and 43 mL/cycle, respectively; P < .001); both groups also showed improvements in QOL.21

Factor replacement

For patients with inherited bleeding disorders (BDs), the exogenous or endogenous increase of the missing factor product can be considered to aid in the treatment of HMB; however, studies confirming the benefit are limited.

DDAVP (1-deamino-8-D-arginine), a synthetic vasopressin, results in the release of von Willebrand factor and factor VIII from endothelial cells and platelets. DDAVP has demonstrated significantly decreased PBAC scores in patients with BDs (−64.1; 95% CI, −88.0, −40.3]).22 In those without BDs, DDAVP improved bleeding compared to placebo; this effect was enhanced by the addition of TXA.23

VWDMin, a randomized crossover study comparing recombinant von Willebrand factor vs TXA for the treatment of HMB, showed in interim analysis the superiority of TXA (median PBAC score, 146; 95% CI, 117-199] vs 213 [152-298]).24

Combined hormonal therapies

Combined hormonal therapies containing both estrogen and progesterone suppress the endogenous production of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, respectively, which suppresses ovulation and endogenous estrogen production. A decrease in estrogen production combined with a progestogenic effect thins the lining of the uterus, resulting in decreased menstrual flow.

Several formulations and doses of COCs are available, any of which may be beneficial for HMB. COCs require daily pill administration, and formulations include standard (placebo pills every 4 weeks) and extended (prolonged interval between placebo weeks) dosing. Older nonrandomized studies demonstrated a decrease in MBL with a 30 µg ethinyl estradiol and 150 µg desogestrel COC.25 Multiple RCTs since that time have compared various COCs with other interventions and demonstrated a wide range of decreased bleeding (35%-79% reduction in MBL).26 A multiphasic estradiol valerate and dienogest combination has been compared with placebo and showed a decrease in MBL and improved hemoglobin.27 Currently, multiphasic estradiol valerate and dienogest is the only COC with FDA approval for the treatment of HMB.

There are 2 FDA-approved transdermal contraceptive formulations, which are replaced on a weekly basis and removed for the fourth week, during which bleeding occurs. No specific comparison studies have evaluated the decrease in MBL for patients utilizing transdermal contraceptive patches; however, 12-week extended-cycle use vs standard use resulted in fewer bleeding days.28

The FDA has approved 2 vaginal contraceptive rings, which are left in place for 3 weeks and then removed by the user for the fourth week, during which bleeding occurs. Extended use is possible by skipping the removal week. No specific studies have evaluated the decrease in MBL using a vaginal ring compared to placebo. A 2019 Cochrane review evaluated studies comparing the vaginal ring with COCs and found comparable reductions in MBL and similar rates of satisfaction, with decreased nausea compared to COCs.29 Studies comparing extended-cycle regimens with standard use demonstrate that extended-cycle use resulted in fewer bleeding days but increased spotting and breakthrough bleeding.30

Progesterone-only hormonal therapies

The mechanism by which progesterone-only therapies decrease menstrual flow varies with administration. Cyclic progesterone may thin the endometrial lining and decrease angiogenesis. When used continuously, some progesterone formulations may suppress ovulation and decrease endogenous estrogen production, thinning the endometrial lining. Most progesterone-only therapies are available by prescription only, and intrauterine and subdermal implants are placed by medical providers. In 2023 the FDA approved the 75-µg norgestrel progesterone-only pill (POP) for over-the-counter use. Unscheduled bleeding tends to be more common with progesterone-only hormonal therapies compared to combined hormonal therapies and is a significant factor in the discontinuation of progesterone-only therapies.31 None of the progesterone formulations described have been compared with placebo in the assessment of HMB/MBL.

Although regimens differ significantly, cyclic oral progesterone therapy is typically administered in the luteal phase starting on cycle days 15 to 19 and continuing through cycle days 23 to 26. Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethindrone acetate, and norethisterone regimens have all been described. Cyclic progesterone regimens are noncontraceptive. The few studies investigating the benefit of cyclic progesterone for HMB show variable results.32

Continuous oral progesterone therapy is administered daily. Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate and oral norethindrone acetate are the most common. Although continuous progesterone regimens likely result in ovulation suppression, their efficacy for contraception have never been explicitly studied. A 2019 Cochrane review evaluated studies comparing long-cycle progesterone regimens with other regimens for HMB and found a significant reduction in MBL with long-cycle progesterone. However, long-cycle progesterone was outperformed by the L-IUS.32

Currently, there are 3 FDA-approved POPs. The 35-µg norethindrone minipill demonstrates more frequent and longer bleeding coupled with less predictable bleeding.31 Both the 4-mg drospirenone pill and the 75-µg norgestrel pill showed potential for an improved bleeding profile with increased duration of use, although unscheduled spotting and variability have been noted.33,34

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate is administered every 12 to 14 weeks. Amenorrhea rates are favorable for treatment, 50% at 1 year and 68% to 71% at 2 years; however, irregular bleeding has been reported in up to 70% of users in the first year of use.35

The 68-mg etonogestrel subdermal contraceptive implant has limited use for HMB. In a systematic review of 11 clinical trials, 18% of users experienced frequent bleeding, 27% experienced prolonged bleeding, and 22% experienced amenorrhea. Approximately 11% of users discontinued the implant due to bleeding irregularities.36

The FDA has approved 4 L-IUSs with varied dosing. IUSs are placed by trained medical providers, and their duration of efficacy varies. While all L-IUSs may ultimately provide some benefit for HMB, the 20-µg/d devices have been the most studied. Nulliparity and adolescent age are not contraindications to L-IUS placement.37 A 2023 study found that among patients with quantified HMB (>80 mL/cycle), treatment with L-IUS resulted in a 93% and 97% reduction in MBL compared to baseline after 3 and 6 cycles, respectively. The discontinuation rate for bleeding and/or cramping (6%) and expulsion (5%) were low in the study period.38 A 2013 randomized trial demonstrated that patients with HMB treated with the L-IUS had sustained improvement in QOL compared to patients treated with the “usual medical treatment,” which included NSAIDs, TXA, continuous oral progesterone, COC pills, POPs, or the progesterone-only injectable contraceptive.39 A 2019 study found that amenorrhea and infrequent bleeding rates were highest in the 20-µg/d device compared to lower-dose devices.40

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

After reviewing menstrual-management options, the patient elects to start a COC pill due to her desire for regular menses and her familiarity with “the pill” because some of her friends use it. A hemostatic evaluation is completed and is reassuring prior to starting the COC pill. The patient returns to your office after 5 months of treatment. She describes initially struggling with compliance, which has since improved with cell phone reminders. She notes improved menses, most significantly with her last period. She states that she bled for 4 days, the last of which was very light. On the other days, she used 3 tampons during the day and did not saturate her pad overnight. Overall, she is happy and comments that her periods were perhaps heavier than she realized. She then asks about extending the time between her periods to minimize the impact of bleeding even further.

Conclusions

Overall, the quantification and nonsurgical treatment of HMB can be difficult and require physicians to listen and consider the personality and goals of the patient. We need to adapt when our patients are unable to provide clear quantification data and trust their personal reports of bleeding and the impact of HMB on their QOL. When treatment decisions are made, the options vary in impact, contraindications, and goals; personal considerations and shared decision-making are needed. Patients should be encouraged to consider what evaluation and treatment options will best fit their personal needs.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Allison P. Wheeler: no competing financial interests to declare.

Celeste O. Hemingway: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Allison P. Wheeler: Use of hormonal medications for menstrual management, while approved for contraception, have not been specifically approved for management of bleeding unless otherwise noted.

Celeste O. Hemingway: Use of hormonal medications for menstrual management, while approved for contraception, have not been specifically approved for management of bleeding unless otherwise noted.