Abstract

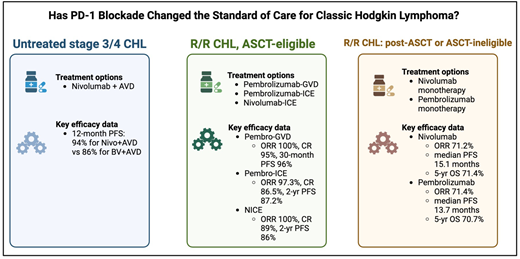

The treatment paradigm for classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) continues to evolve, particularly in light of the incorporation of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors into a variety of therapeutic settings. PD-1 inhibitors have demonstrated high efficacy and a favorable toxicity profile when added to a doxorubicin, vinblastine, dacarbazine chemotherapy backbone in patients with untreated CHL. PD-1 inhibitors are also effective treatment options in the relapsed/refractory setting. For patients who are pursuing autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), pembrolizumab plus gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and liposomal doxorubicin has shown marked efficacy and is an effective treatment regimen to administer prior to transplant. For patients who either are not eligible for ASCT or have relapsed after ASCT, pembrolizumab or nivolumab monotherapy have been well studied and demonstrate high efficacy even when patients have been exposed to numerous lines of prior therapy. As data from previous trials continue to mature and new clinical trials are conducted, PD-1 inhibitors will continue to become an integral component for successful management of CHL.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the role of PD-1 inhibitors in untreated advanced-stage and relapsed/refractory classic Hodgkin lymphoma

Describe the safety and efficacy data of PD-1 inhibitors in the treatment of classic Hodgkin lymphoma

Highlight unanswered research questions related to PD-1 inhibitors that warrant further investigation

CLINICAL CASE

A 65-year-old male presented with night sweats, weight loss, and progressive lymphadenopathy. He underwent an excisional lymph node biopsy, which confirmed a diagnosis of classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL). A positron emission tomography (PET) scan demonstrated metabolically active lymph nodes above and below the diaphragm, as well as involvement of the spleen and liver. His past medical history was notable for hypertension, diabetes, and peripheral neuropathy. Various treatment options were discussed prior to initiation of treatment.

Introduction

With the advent of targeted immunotherapies, the treatment paradigm for CHL continues to evolve. PD-1 inhibitors have demonstrated high efficacy in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, including one of the highest objective response rates for this class of drug seen in any malignancy in relapsed/refractory (R/R) CHL.1,2 In addition to their impressive efficacy, PD-1 inhibitors are also an appealing therapeutic agent due to their favorable toxicity profile. Minimizing toxicity is of considerable importance for a disease in which the median age of diagnosis is 39 years,3 as younger patients must cope with residual long-term effects, and side effects from traditional chemotherapy, such as infertility, are more consequential.

These agents have been the focus of numerous recent clinical trials in both the frontline and R/R settings. We review the role of PD-1 inhibitors in 3 separate clinical settings: untreated advanced-stage CHL (defined as either stage III or IV disease), R/R disease for patients eligible for autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), and R/R disease for patients who are ineligible for transplant or progressed after ASCT. In each setting, we review the key efficacy and safety data and highlight pertinent findings for specific subpopulations.

Untreated advanced-stage classic Hodgkin lymphoma

Standard frontline treatment for advanced-stage CHL typically includes doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) or brentuximab vedotin (BV) with doxorubicin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (AVD). Other treatment regimens include escalated BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone) in a PET-adapted approach and BrECADD (BV, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, dacarbazine, dexamethasone), which has recently shown superiority over escalated BEACOPP in the HD21 trial.4,5 During the past several years, clinical trials investigating the role of PD-1 inhibitors in the frontline setting for patients with CHL have demonstrated promising results (Table 1). PD-1 inhibitors were first evaluated using a sequential approach, which consisted of PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy followed by chemotherapy or combination chemoimmunotherapy.6,7 Patients in the CheckMate 205 cohort D study received 4 cycles of nivolumab followed by 12 cycles of nivolumab plus AVD.6 This approach proved effective with a 21-month progression-free survival (PFS) of 83%.8 Another study that also used a sequential approach—3 cycles of pembrolizumab followed by 4 to 6 cycles of AVD—demonstrated an even higher PFS of 100% at 33 months.9

Efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors for untreated advanced-stage classic Hodgkin lymphoma

| Author, year . | Study design . | Number of patients . | Key efficacy results . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ramchandren et al 20196 | Sequential nivolumab × 4, Nivolumab+AVD × 12 | 51 | 21-month PFS 83%8 |

| Allen et al 20217 Allen et al 20219 | Sequential Pembrolizumab+AVD | 30 | 33-month PFS 100%9 |

| Lynch et al 202310 Lynch et al 202311 | Pembrolizumab+AVD × 2-6 | 50 | 2-year PFS 97%11 |

| Herrera et al 202312 | Nivolumab+AVD vs BV+AVD | 994 | 12-month PFS 94%12 |

| Author, year . | Study design . | Number of patients . | Key efficacy results . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ramchandren et al 20196 | Sequential nivolumab × 4, Nivolumab+AVD × 12 | 51 | 21-month PFS 83%8 |

| Allen et al 20217 Allen et al 20219 | Sequential Pembrolizumab+AVD | 30 | 33-month PFS 100%9 |

| Lynch et al 202310 Lynch et al 202311 | Pembrolizumab+AVD × 2-6 | 50 | 2-year PFS 97%11 |

| Herrera et al 202312 | Nivolumab+AVD vs BV+AVD | 994 | 12-month PFS 94%12 |

AVD, adriamycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine; BV+AVD, brentuximab vedotin, adriamycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine; PFS, progression-free survival.

Although effective, sequential approaches can prolong the total duration of therapy. Concurrent approaches, which deliver immunotherapy and chemotherapy together from treatment outset and are shorter, have demonstrated promising results. In one of the first trials to use a concurrent approach in patients with advanced-stage CHL, 50 patients were treated with concurrent pembrolizumab-AVD for 2 to 6 cycles depending on stage and baseline risk factors.10,11 Patients with advanced-stage disease in this study demonstrated a 2-year overall survival and PFS of 100% and 97%, respectively.11 Importantly, the high PET2 false positivity rate (42% in advanced stage) despite extremely low relapsed rate calls into question the role of interim PET imaging when using concurrent chemotherapy and PD-1 inhibitors.11 Rates of serious adverse events were relatively low, and although 8 patients missed at least 1 dose of pembrolizumab—the majority of which were for grade ≥2 transaminitis—this did not appear to compromise overall efficacy. There did appear to be higher than expected rates of any grade elevated transaminases and neutropenia, though these were reversible and did not appear to affect outcomes.11

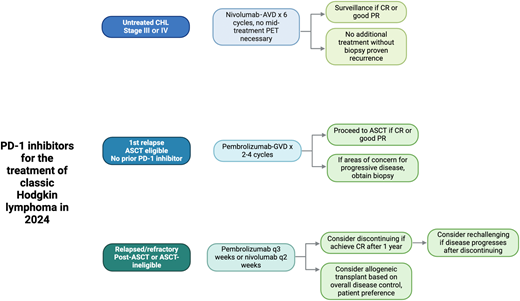

The largest study to date of PD-1 inhibitors combined with chemotherapy for untreated CHL is the SWOG 1826 trial, in which 976 patients were randomized to 6 cycles of either concurrent nivolumab-AVD (N-AVD) or BV-AVD.12 Data are still maturing, but an interim 12-month analysis highlighted a PFS of 94% for patients receiving nivolumab-AVD compared with only 86% treated with BV-AVD. Importantly, the 2 treatment arms had similar rates of febrile neutropenia, pneumonitis, and transaminase elevations. Patients receiving N-AVD had higher rates of thyroid dysfunction, whereas those who received BV-AVD experienced more peripheral neuropathy (54.2% vs 28.1%).12 If the results of this study are sustained over time, use of PD-1 inhibitors in the frontline setting for advanced-stage CHL will become standard practice (Figure 1).

PD-1 inhibitors for the treatment of CHL in 2024. Figures were created with BioRender.

PD-1 inhibitors for the treatment of CHL in 2024. Figures were created with BioRender.

Data for frontline PD-1 inhibitors are also compelling in older populations. Older adults with CHL historically have lower survival rates and higher rates of treatment-associated toxicities when treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy. In a subset analysis of 95 patients aged ≥60 years in the S1826 study, those who received N-AVD had lower rates of sensory neuropathy (31% vs 66%) and sepsis (6% vs 21%) when compared with those who received BV-AVD.13 Older adults receiving N-AVD had comparable outcomes to the overall study population and superior 1-year PFS (93% vs 64%) and 1-year overall survival (95% vs 83%). Similar to the results of the ECHELON-1 study, older adults receiving BV-AVD in S1826 performed worse overall, with 1-year PFS of 64%.13,14 Treatment discontinuation was greater in the BV-AVD group, with 33% of patients in the BV-AVD group discontinuing treatment compared with only 10% in the N-AVD group.13 As most patients discontinued the treatment because of adverse events, the increased tolerability of N-AVD may make it particularly appealing in older, more comorbid patients.

As N-AVD and BrECADD are poised to become the new standards for most patients with untreated advanced-stage CHL, additional follow-up will help define the comparison of treatment efficacy as well as short- and long-term effects. So far, these discussions are similar to previous debates between the merits of ABVD vs escalated BEACOPP, comparing a less toxic regimen with lower rates of upfront disease control with one that is more toxic but cures more patients.15 Thankfully, both N-AVD and BrECADD are highly effective and significant improvements on the regimens that preceded them.

R/R CHL: eligible for ASCT

Although there is no standard treatment regimen for R/R CHL, management of ASCT-eligible patients has historically involved intensive combination chemotherapy followed by ASCT upon achieving a complete response (CR). Targeted immunotherapy, including BV and PD-1 inhibitors, has been explored in this setting. One of the first studies to demonstrate the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors as first salvage treatment in the R/R setting combined BV plus nivolumab.16 In this study, patients received 4 cycles of BV and nivolumab and subsequently underwent ASCT per the discretion of their treating physician. Results with this chemotherapy-free regimen were quite favorable, demonstrating an ORR of 85% and 3-year PFS of 77%.16 Another study of 43 patients with R/R CHL treated with a response-adapted approach using nivolumab or combination nivolumab plus ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide (ICE) provided additional insight into the efficacy of a chemotherapy-sparing approach. Twenty-six patients achieved a CR and were able to proceed to ASCT with only nivolumab monotherapy, suggesting that PD-1 monotherapy may be sufficient pre-transplant therapy for some patients.

Researchers have also investigated the role of PD-1 inhibitors in combination with intensive chemotherapy in the R/R setting prior to ASCT (Table 2). It is important to note that there is a scarcity of randomized data in this setting, but 1 small, randomized phase 2 trial of pembrolizumab-BV vs gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin is currently enrolling patients (NCT05180097). In 1 single-arm phase 2 study, 38 patients with R/R CHL were treated with pembrolizumab and gemcitabine, vinorelbine, liposomal doxorubicin (GVD) followed by ASCT.17 The majority of patients in this cohort had received ABVD in the frontline setting, and 9 patients had received a BV-containing regimen. After only 2 cycles of pembrolizumab-GVD, 92% of patients achieved a CR, and 36 of 38 patients ultimately proceeded to ASCT. Of these 36 patients, only 1 patient experienced relapsed disease at a median follow-up of 30 months.18 These efficacy rates are significantly higher than historical controls using chemotherapy- only-based regimens.19 Another study enrolled 42 ASCT-eligible patients and treated them with 2 cycles of pembrolizumab and ICE, followed by 1 cycle of pembrolizumab monotherapy.20 Although 5 of 42 patients were excluded for various reasons, 35 of 37 evaluable patients ultimately underwent ASCT, and the ORR and CR rates were 97.3% and 86.5%, respectively.21 PFS was 87.2% at 2 years. Lastly, nivolumab in combination with ICE chemotherapy followed by ASCT has been investigated in the R/R setting. In this trial, patients who received nivolumab-ICE achieved an ORR and a CR of 100% and 89%, respectively.22 Similar to the pembrolizumab-ICE data, PFS was 86% at 2 years for those who received nivolumab-ICE.22

Efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors in relapsed/refractory classic Hodgkin lymphoma

| Author, year . | Study design . | Treatment setting . | Number of patients . | Key efficacy data . | Key toxicity data . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moskowitz et al 202117 Moskowitz et al 202218 | Pembrolizumab-GVD × 2-4 cycles, followed by ASCT | ASCT eligible | 39 | ORR 100%, CR 95% 30-month PFS 96% | Grade ≥3 hepatoxicity 10%; grade ≥3 neutropenia 10% |

| Mei et al 202222 | Nivo × 3, Nivo × 3 and/or Nivo-ICE × 2, then ASCT | ASCT eligible | 43 | Nivo alone: ORR 89%, CR 78%, 2-year PFS 96% Nivo-ICE: ORR 100%, CR 89%, 2-year PFS 86% | 1 case of grade 4 encephalitis; 1 case of grade 3 colitis |

| Bryan et al 202320 | Pembrolizumab-ICE × 2, pembro × 1 | ASCT eligible | 42 | ORR 97.3%, CR 86.5%, 2-year PFS 87.2% | Grade ≥3 hepatoxicity 5%; grade ≥3 neutropenia 36%; 2 grade 5 events |

| Advani et al 202116 | BV+nivolumab | ASCT eligible | 93 | ORR 85%, CR 67%, 3-year PFS 77% | Grade ≥3 pneumonitis 3%, grade ≥3 rash 1%, grade ≥3 AST elevation 1%, Guillain-Barre syndrome 1% |

| Ding et al 202328 | Tislelizumab+GemOx × 6-8, followed by tislelizumab maintenance | Relapsed/refractory; majority without prior ASCT | 30 | ORR 100%, CR 96.7%, 12-month PFS 86% | Grade ≥3 neutropenia 3%, grade ≥3 transaminase elevation 3% |

| Kuruvilla et al 202132 | BV vs pembrolizumab | After prior ASCT or ineligible for ASCT | 153 | Median PFS 13.2 vs 8.3 mos | Grade ≥3 pneumonitis 4% (1 grade 5 event); grade ≥3 neutropenia 2% |

| Chen et al 201938 Armand et al 202329 | KEYNOTE-087: pembrolizumab every 3 weeks up to 2 years | After prior ASCT/BV or salvage chemo/BV or ASCT | 210 | ORR 71.4%, median DOR 16.6 mos, median PFS 13.7 mos, median OS NR, 5-year OS 70.7% | Grade ≥3 neutropenia 2.4%; grade ≥3 pericarditis 1%; grade ≥3 diarrhea 1% |

| Ansell et al 202330 Armand et al 201839 | CheckMate 205: Nivo every 2 weeks until progression or unacceptable toxicity | After prior BV or ASCT or ASCT/BV | 243 | ORR 71.2%, median DOR 18.2 mos, median PFS 15.1 mos, median OS NR, 5-year OS 71.4% | Grade ≥3 hepatitis 4.9%; grade ≥3 colitis 2.1%; grade ≥3 pneumonitis 0.8% |

| Author, year . | Study design . | Treatment setting . | Number of patients . | Key efficacy data . | Key toxicity data . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moskowitz et al 202117 Moskowitz et al 202218 | Pembrolizumab-GVD × 2-4 cycles, followed by ASCT | ASCT eligible | 39 | ORR 100%, CR 95% 30-month PFS 96% | Grade ≥3 hepatoxicity 10%; grade ≥3 neutropenia 10% |

| Mei et al 202222 | Nivo × 3, Nivo × 3 and/or Nivo-ICE × 2, then ASCT | ASCT eligible | 43 | Nivo alone: ORR 89%, CR 78%, 2-year PFS 96% Nivo-ICE: ORR 100%, CR 89%, 2-year PFS 86% | 1 case of grade 4 encephalitis; 1 case of grade 3 colitis |

| Bryan et al 202320 | Pembrolizumab-ICE × 2, pembro × 1 | ASCT eligible | 42 | ORR 97.3%, CR 86.5%, 2-year PFS 87.2% | Grade ≥3 hepatoxicity 5%; grade ≥3 neutropenia 36%; 2 grade 5 events |

| Advani et al 202116 | BV+nivolumab | ASCT eligible | 93 | ORR 85%, CR 67%, 3-year PFS 77% | Grade ≥3 pneumonitis 3%, grade ≥3 rash 1%, grade ≥3 AST elevation 1%, Guillain-Barre syndrome 1% |

| Ding et al 202328 | Tislelizumab+GemOx × 6-8, followed by tislelizumab maintenance | Relapsed/refractory; majority without prior ASCT | 30 | ORR 100%, CR 96.7%, 12-month PFS 86% | Grade ≥3 neutropenia 3%, grade ≥3 transaminase elevation 3% |

| Kuruvilla et al 202132 | BV vs pembrolizumab | After prior ASCT or ineligible for ASCT | 153 | Median PFS 13.2 vs 8.3 mos | Grade ≥3 pneumonitis 4% (1 grade 5 event); grade ≥3 neutropenia 2% |

| Chen et al 201938 Armand et al 202329 | KEYNOTE-087: pembrolizumab every 3 weeks up to 2 years | After prior ASCT/BV or salvage chemo/BV or ASCT | 210 | ORR 71.4%, median DOR 16.6 mos, median PFS 13.7 mos, median OS NR, 5-year OS 70.7% | Grade ≥3 neutropenia 2.4%; grade ≥3 pericarditis 1%; grade ≥3 diarrhea 1% |

| Ansell et al 202330 Armand et al 201839 | CheckMate 205: Nivo every 2 weeks until progression or unacceptable toxicity | After prior BV or ASCT or ASCT/BV | 243 | ORR 71.2%, median DOR 18.2 mos, median PFS 15.1 mos, median OS NR, 5-year OS 71.4% | Grade ≥3 hepatitis 4.9%; grade ≥3 colitis 2.1%; grade ≥3 pneumonitis 0.8% |

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BV, brentuximab vedotin; CR, complete response; DOR, duration of response; GemOx, gemcitabine, oxaliplatin; GVD, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, liposomal doxorubicin; ICE, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide; mos, months; NR, not reached; ORR, objective response rate; PFS, progression-free survival.

With multiple chemoimmunotherapy combinations available in the R/R setting, clinicians should be mindful of the unique toxicities associated with these agents and understand how to manage them, particularly immune-related adverse events.23,24 While both pembrolizumab-GVD and pembrolizumab-ICE did not have any life-threatening immune-related adverse events, patients did experience thyroid dysfunction, transaminitis, and rash that were believed to be related to immunotherapy.17,20 One other important adverse event that has been associated with PD-1 inhibitor exposure prior to ASCT is engraftment syndrome.25 In the pembrolizumab-GVD study, 68% of patients experienced engraftment syndrome, and the pembrolizumab-ICE study had 1 fatal case of engraftment syndrome.17,20 Rates of engraftment syndrome in other studies involving PD-1 inhibitors prior to ASCT were less common, ranging from 12% to 18%.22,26 As clinicians continue to use immunotherapy more frequently prior to ASCT, further investigation into the risk factors and management of engraftment syndrome for this specific patient population is needed.

With combination chemoimmunotherapy yielding such high CR rates, it is also reasonable to ask whether undergoing ASCT is even necessary at all in the R/R setting.27 One study by Ding et al has already published data on an ASCT-free approach, and 2 ongoing trials are exploring this question in greater depth.28 In the trial by Ding et al, patients with R/R CHL were treated with 6 to 8 cycles of tislelizumab and gemcitabine/oxaliplatin, followed by tislelizumab maintenance for up to 2 years.28 While data for this trial are still maturing, patients demonstrated a 12-month PFS of 96%.28 Moskowitz et al are conducting an expansion cohort trial in which 40 patients with R/R HL are treated with 4 cycles of pembrolizumab-GVD, and upon achieving a CR are subsequently given 13 cycles of maintenance pembrolizumab rather than proceeding to ASCT (NCT03618550). While the trial is still recruiting, an interim analysis of the first 33 patients demonstrated a high CR rate of 90% with a relatively safe toxicity profile, though 1 patient did develop grade 5 pneumonitis.18 Meanwhile, Herrera et al have an ongoing clinical trial in which patients receive 4 cycles of BV-nivolumab, followed by an additional 12 cycles of BV-nivolumab if they achieve a CR (NCT04561206). As data from these trials mature, the role of ASCT and PD-1 inhibitors for patients with R/R CHL will likely continue to evolve.

R/R CHL: post-transplant or transplant ineligible

While undergoing an ASCT is the goal for many patients with R/R CHL, some patients are not eligible for an ASCT. Other patients relapse after having already received an ASCT. The KEYNOTE-087 and CheckMate 205 trials highlight the role of PD-1 inhibitors in this setting. In the KEYNOTE-087 study, patients who had previously received ASCT and/or BV were treated with pembrolizumab every 3 weeks for up to 2 years.29 The ORR was 71.4% and the median duration of response (DOR) was 16.6 months. Five-year overall survival was 70.7%.29 Patients in this cohort were heavily pretreated, with a median exposure to 4 prior lines of therapy. Importantly, 20 patients in this cohort who initially achieved a CR and discontinued treatment ultimately progressed and were restarted on pembrolizumab. The ORR for this group after their second course of pembrolizumab was 73.7% with a median DOR of 15.2 months, highlighting that resuming pembrolizumab can be quite effective for some patients.29

Similar to the KEYNOTE-087 trial, CheckMate 205 enrolled 243 patients with R/R CHL who had predominantly been treated with BV and/or ASCT. These patients were treated with nivolumab every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The 5-year analysis of this study was strikingly similar to that of KEYNOTE-087, with an ORR of 71.2% and a median DOR of 18.2 months.30 Five-year overall survival was 71.4%. These findings suggest that treatment with PD-1 inhibitors beyond radiographic progression can be warranted, as long as patients are deriving a clinical benefit and are remaining relatively asymptomatic.31

The KEYNOTE-204 trial also underscored the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors in the post-ASCT or ASCT-ineligible context. In this trial, patients who either had R/R CHL after ASCT or were ineligible for ASCT were randomized to either pembrolizumab or BV for up to 2 years or until disease progression.32 Patients who received pembrolizumab had higher PFS (13.2 months) than those who received BV (8.3 months). Patients treated with BV had higher rates of peripheral neuropathy (18% vs 2%), while those treated with pembrolizumab had higher rates of pneumonitis (8% vs 1%).32 Peripheral neuropathy was the most common treatment-related adverse event leading to drug discontinuation.

Patients with multiply R/R disease who are already post-ASCT may be eligible for an allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloSCT). One ongoing area of research is the role and timing of alloSCT after PD-1 blockade for patients with R/R disease. Interestingly, while exposure to PD-1 inhibitors prior to allogeneic transplant is associated with improved PFS and survival outcomes, it is also linked with higher rates of transplant-associated toxicities, including acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome.33,34 One retrospective cohort of 209 patients treated with allogeneic transplant after PD-1 blockade found that when PD-1 inhibitors were given ≤80 days from time of transplant, risk of developing grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD increased by 2.5-fold.34 Yet these patients overall had relatively lower rates of relapsed disease, possibly due to increased activity of alloreactive T cells leading to greater antitumor activity.34 The timing of PD-1 inhibitor in relation to alloSCT is a clinically significant factor and one that should be further investigated. The specific GVHD prophylaxis regimen is also an important consideration. Post-transplant cyclophosphamide, while not associated with a lower risk of acute GVHD, was associated with improved GVHD and relapse-free survival, as well as PFS in patients with prior PD-1 treatment.34

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient was started on concurrent N-AVD. If this patient had a clear contraindication to receiving chemotherapy, BV-nivolumab could be considered as an alternative treatment option.35,36 This regimen remains a reasonable chemotherapy-free option that may formally become integrated into expert guidelines in the near future. He received a total of 6 cycles of N-AVD without experiencing any major adverse events. Post-treatment PET imaging revealed a complete response, and he remains disease-free several years out from diagnosis.

Conclusions and future directions

PD-1 inhibitors are changing the standard of care for CHL. In the frontline setting, incorporation of PD-1 inhibitors into AVD chemotherapy backbone seems to improve efficacy while still maintaining a favorable toxicity profile. Additional follow-up from S1826 and HD21 will help inform patients and providers about the degree of difference in efficacy between N-AVD over BrECADD compared with the clear improvement in toxicity profile observed with N-AVD. While nivolumab is already an option in frontline management of advanced-stage CHL in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, we expect that nivolumab will eventually be approved in the frontline setting, particularly as data from S1826 continue to mature. In the R/R and ASCT-eligible setting, the addition of PD-1 inhibitors to intensive chemotherapy has also shown tremendous efficacy17,20,22 to the point that ASCT may not even be necessary for some patients, leading to the next generation of studies in this setting. For R/R patients who have received a prior ASCT or are ASCT ineligible, PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy is an effective treatment strategy in patients even when heavily pretreated with other chemotherapies.

Despite the extensive research already conducted involving PD-1 inhibitors in patients with CHL, there are still many questions worthy of investigation. For instance, in light of promising results in the NIVAHL trial, what is the role of immunotherapy in early-stage disease, and, in particular, can it be used in isolation rather than in combination with chemotherapy (NCT04837859)?37 Moreover, what is the role of consolidative radiotherapy after PD1-inhibitor and chemotherapy combinations for frontline treatment in early-stage disease? For patients who have progressed after first-line PD-1 blockade, what is the optimal salvage regimen? Given that false-positive PET scans are relatively common when using PD-1 inhibitors,10 is there still a role for PET-adapted treatment algorithms in the era of PD-1 inhibitors? Are there predictors of PD-1 inhibitor response that can help guide selection of therapy and retreatment upon progression of disease? Moreover, is there a role for novel techniques, such as circulating tumor DNA-based MRD assays, to determine treatment response to PD-1 inhibitors? What is the optimal duration of PD-1 inhibitor therapy in the upfront setting and as a maintenance therapy in the R/R setting? Ongoing and future investigations into these questions, among many others, may help further solidify PD-1 inhibitors into the treatment guidelines for CHL.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Thomas M. Kuczmarski: no competing financial interests to declare.

Ryan C. Lynch: consultancy/honoraria: Seagen, Foresight Diagnostics, AbbVie, Janssen, Merck; research funding: TG Therapeutics, Incyte, Bayer, Cyteir, Genentech, Seagen, Rapt, Merck, Janssen.

Off-label drug use

Thomas M. Kuczmarski: nothing to disclose.

Ryan C. Lynch: nothing to disclose.