Abstract

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a rare hematologic malignancy with a bimodal distribution of incidence, with most patients diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 30 years and another peak in patients older than 55 years. It is estimated that in 2023, almost 9000 people were diagnosed with HL in the United States. Most patients will be cured using conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The treatment of HL has changed significantly over the past decade following the approval of highly effective novel therapies, including brentuximab vedotin and the checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs) nivolumab and pembrolizumab. The increasing use of these novel therapies has resulted in decreased utilization of both autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) in patients with HL. In this review, we discuss the role of stem cell transplantation in patients with HL, with a particular focus on recent data supporting allogeneic HCT as a curative option in patients who progress on or are intolerant to CPI treatment.

Learning Objectives

Understand the role of stem cell transplantation for Hodgkin lymphoma in the era of novel therapies

Understand the impact of prior checkpoint inhibitor use in patients undergoing an allogeneic HCT for Hodgkin lymphoma

Introduction

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a rare hematologic malignancy with a bimodal distribution of incidence, with most patients diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 30 years and another peak in patients aged 55 years and older. It is estimated that in 2023 almost 9000 people were diagnosed with HL in the United States. Most patients will be cured using conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The treatment of HL has changed significantly over the past decade following the approval of highly effective novel therapies, including brentuximab vedotin (BV) and the checkpoint inhibitors (CPI) nivolumab and pembrolizumab.1-8 This has resulted in the decreased utilization of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and particularly allogeneic HCT in patients with HL.9-13 In this review we discuss the role of stem cell transplantation in patients with HL, with a particular focus on recent data supporting allogeneic HCT as a curative option in patients who progress on or are intolerant to CPI treatment (Tables 1 and 2).

Summary of treatment recommendations for autologous HCT for Hodgkin lymphoma

| Recommendation . | |

|---|---|

| Autologous HCT should be offered as first-line therapy for patients who fail to achieve CR. | |

| Autologous HCT should be offered as salvage therapy over nontransplantation (except for localized disease, in which IFRT may be considered, or for patients with low-stage disease and late relapse, in which chemotherapy may be considered). | |

| Several salvage chemotherapy regimens may be considered prior to autologous HCT in adult patients. | |

| BEAM or CBV are the most common conditioning regimens for autologous HCT in standard-risk patients. | |

| IFRT should be considered in patients with bulky disease not previously irradiated. | |

| Tandem autologous HCT is not routinely recommended in standard-risk patients. | |

| Maintenance therapy with brentuximab vedotin post autologous HCT is recommended in high-risk patients.a Additional maintenance therapies incorporating CPI are under investigation. | |

| Chemosensitive disease and negative functional imaging are associated with improved outcomes. | |

| Recent data with novel agents + chemotherapy +/− radiation in the second line suggests that in a highly selected population, some patients may not need to proceed with autologous HCT if they achieve a complete response. | |

| Recommendation . | |

|---|---|

| Autologous HCT should be offered as first-line therapy for patients who fail to achieve CR. | |

| Autologous HCT should be offered as salvage therapy over nontransplantation (except for localized disease, in which IFRT may be considered, or for patients with low-stage disease and late relapse, in which chemotherapy may be considered). | |

| Several salvage chemotherapy regimens may be considered prior to autologous HCT in adult patients. | |

| BEAM or CBV are the most common conditioning regimens for autologous HCT in standard-risk patients. | |

| IFRT should be considered in patients with bulky disease not previously irradiated. | |

| Tandem autologous HCT is not routinely recommended in standard-risk patients. | |

| Maintenance therapy with brentuximab vedotin post autologous HCT is recommended in high-risk patients.a Additional maintenance therapies incorporating CPI are under investigation. | |

| Chemosensitive disease and negative functional imaging are associated with improved outcomes. | |

| Recent data with novel agents + chemotherapy +/− radiation in the second line suggests that in a highly selected population, some patients may not need to proceed with autologous HCT if they achieve a complete response. | |

High-risk patients were defined in the AETHERA trial as having 1 of the following: refractory to frontline therapy, relapse less than 12 months after frontline therapy, or relapse 12 months or more after frontline therapy with extranodal disease.

BEAM, BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan; CBV, cyclophosphamide, carmustine (BCNU), etoposide; GVD, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and liposomal doxorubicin.

Adapted with permission from Perales et al.9

Summary of treatment recommendations for allogeneic HCT for Hodgkin lymphoma

| Recommendation . | |

|---|---|

| Most patients who relapse after autologous HCT will receive CPIs rather than conventional therapy. | |

| Allogeneic HCT should be used instead of conventional therapy for relapse after autologous HCT. | |

| RIC is the recommended regimen intensity. | |

| All donor sources (except cord blood) can be considered. | |

| PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis is considered standard and is preferred in patients with prior CPI. | |

| Allogeneic HCT can be considered in patients as soon as they achieve CR after CPI but is typically deferred to relapse/progression or because of lack of response or intolerance. | |

| DLI can be given for relapse or progressive disease (limited data for mixed-donor chimerism). | |

| Recommendation . | |

|---|---|

| Most patients who relapse after autologous HCT will receive CPIs rather than conventional therapy. | |

| Allogeneic HCT should be used instead of conventional therapy for relapse after autologous HCT. | |

| RIC is the recommended regimen intensity. | |

| All donor sources (except cord blood) can be considered. | |

| PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis is considered standard and is preferred in patients with prior CPI. | |

| Allogeneic HCT can be considered in patients as soon as they achieve CR after CPI but is typically deferred to relapse/progression or because of lack of response or intolerance. | |

| DLI can be given for relapse or progressive disease (limited data for mixed-donor chimerism). | |

DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion.

Adapted with permission from Perales et al.9

CLINICAL CASE

A 37-year-old woman was diagnosed with stage IIB classical Hodgkin lymphoma presenting with a right cervical lymph node. She received 6 cycles of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) and achieved a complete remission (CR) based on positron emission tomography (PET). A PET scan performed 6 months after the completion of therapy showed recurrent disease, which was confirmed on biopsy. She received 3 cycles of ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE) and achieved a PET CR. She then underwent autologous HCT. The patient declined maintenance therapy with BV due to logistics and was monitored clinically and with regular scans. Eighteen months after her autologous HCT, she was again found to have biopsy-proven recurrent disease. She was treated with a combination of nivolumab and BV and referred for consultation for allogeneic HCT.

Novel agents

Brentuximab vedotin

Brentuximab vedotin is an antibody-drug conjugate consisting of a recombinant chimeric immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody directed against CD30 that is covalently linked to monomethyl auristatin E. The drug was initially approved in patients with relapsed or refractory HL after autologous HCT based on overall response rates (ORRs) of up to 75%.2

Checkpoint inhibitors

A series of large prospective trials examined the role of the CPIs nivolumab or pembrolizumab in patients with relapsed/refractory HL with or without prior BV exposure and/or prior autologous HCT.6,8,14,15 Objective response rates ranged from 64% to 74% depending on the specific cohorts studied, with a median duration of response over 16 months and a median progression-free survival (PFS) of about 14 months. Based on these promising results, CPIs are routinely used in the treatment of HL and are being studied in earlier lines of treatment. The combination of pembrolizumab with gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and liposomal doxorubicin (pembro-GVD) has been shown to be effective in second-line therapy in a phase 2 trial.16 Overall and CR rates were 100% and 95%, respectively, and 95% of patients proceeded to autologous HCT. There are ongoing studies evaluating whether patients receiving these combinations may avoid the need for autologous HCT.17-20 Current practice for salvage therapy includes novel therapy, and most patients have been exposed to both BV and CPIs by the third line of treatment. Historically, a number of cytotoxic salvage regimens have been utilized; however, there is no compelling evidence that any one of them is superior in terms of disease control, and the objective response rates range from 60% to 80%.21 Patients who proceed to autologous transplant with the disease in a metabolic complete response have superior outcomes compared to those who do not.22 The development of antibody-targeted therapies as monotherapy, particularly in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy, has demonstrated higher levels of efficacy and reduced toxicity. Recent data highlight the fact that CPI-based regimens have been associated with superior 2-year PFS compared to conventional chemotherapy in patients who subsequently receive a consolidative autologous transplant.23Table 3 highlights the outcomes of modern salvage regimens.

Salvage chemotherapy + novel agent salvage therapy in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma

| Regimen . | Number of patients . | ORR (%) . | CR (%) . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential BV-chemo | 37 | 68a | 35a | 24 |

| BV- ESHAP | 66 | 91a | 70a | 25 |

| BV-ICE | 16 | 94a | 69a | 26 |

| BV-DHAP | 12 | 100a | 100a | 27 |

| BV-bendamustine | 55 | 93a | 74a | 28 |

| BV-nivolumab | 90 | 85a | 67a | 29 |

| Nivolumab (nivo-ICE) | 42 (34 nivolumab alone) | Nivo 81%a NICE 100%a | Nivo 71%aNICE 89%a | 30 |

| Pembrolizumab-GND | 38 | 100%a | 95%a | 16 |

| Regimen . | Number of patients . | ORR (%) . | CR (%) . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential BV-chemo | 37 | 68a | 35a | 24 |

| BV- ESHAP | 66 | 91a | 70a | 25 |

| BV-ICE | 16 | 94a | 69a | 26 |

| BV-DHAP | 12 | 100a | 100a | 27 |

| BV-bendamustine | 55 | 93a | 74a | 28 |

| BV-nivolumab | 90 | 85a | 67a | 29 |

| Nivolumab (nivo-ICE) | 42 (34 nivolumab alone) | Nivo 81%a NICE 100%a | Nivo 71%aNICE 89%a | 30 |

| Pembrolizumab-GND | 38 | 100%a | 95%a | 16 |

PET negative.

DHAP, dexamethasone, cisplatin, cytarabine; ESHAP, etoposide, solumedrol, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin; GND, gemcitabine, navelbine, doxorubicin; NICE, nivolumab-ICE.

Role of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation in Hodgkin Lymphoma

High-dose chemotherapy and autologous HCT remain the standard of care for treatment of relapsed or refractory HL with chemosensitive disease (Table 1).9,31-33 Schmitz et al randomized 161 patients with relapsed HL to autologous HCT vs chemotherapy.32 Of these, 144 had chemosensitive disease and proceeded to autologous HCT. Freedom from treatment failure at 3 years was significantly improved among patients who underwent autologous HCT (55%) compared to those treated with chemotherapy (34%; P = .019), though there was no difference in overall survival (OS). A Cochrane review concluded that salvage therapy with autologous HCT improved event-free survival (EFS) and PFS compared to non-HCT treatment but that the benefit for OS only showed a positive trend in favor of autologous HCT.33 In some patients with localized late relapses, consideration may be given to chemotherapy or involved field radiation therapy (IFRT) only when the lesion is amenable to this approach.34-36

Use of novel agents in the context of autologous HCT

The AETHERA trial was a multicenter randomized trial that showed a significant prolongation of PFS when BV was used as maintenance after autologous HCT in patients with high-risk HL.3 Risk factors included 1) refractory to frontline therapy, 2) relapse fewer than 12 months after initial therapy, or 3) relapse more than 12 months after initial therapy with extranodal disease. Three hundred and twenty-nine BV-naive patients with relapsed/refractory HL were randomly assigned to BV maintenance therapy (every 3 weeks for up to 16 cycles) or placebo, starting 30 to 45 days after HCT. At 5-year follow-up, the 5-year PFS favored BV over placebo (59% vs 41%,), including significant benefit in patients with 2 or more risk factors. The main toxicity was peripheral neuropathy, which was reversible in most patients. Based on this trial, the US Food and Drug Administration approved BV for postautologous HCT maintenance for HL.

More recent maintenance trials post autologous HCT have examined the role of adding CPIs with nivolumab (ongoing NCT03436862),37 or with pembrolizumab for 8 cycles post transplant, which revealed, among evaluable patients, an 18-month PFS of 82% and an OS of 100%.38 Nivolumab in combination with BV is highly active post autologous HCT in high-risk patients with prior BV or CPI exposure, as demonstrated in a phase 2 trial in which patients received 8 cycles of BV-nivolumab every 21 days. The 18-month PFS in all 59 patients was 94% (95% CI, 84-98).39 The ongoing role for autologous HCT in HL in the era of effective novel therapies was reviewed in detail by Dr. Alison Moskowitz in 2022, and the reader is referred to that publication for further information.17 We focus the remainder of our discussion on the role of allogeneic HCT in HL.

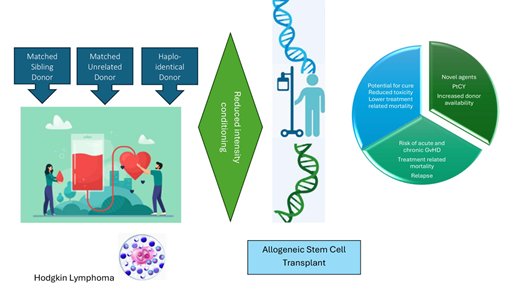

Role of allogeneic HCT in HL

The increasing use of BV and CPIs in patients with HL has resulted in decreased utilization of allogeneic HCT, which has long been considered the standard treatment in patients who relapse after autologous HCT (Table 2).9-13,40 In a multivariate analysis of 185 patients who relapsed after autologous HCT, the 2 factors associated with significantly improved OS and PFS were having a donor for HCT and relapse beyond 12 months after autologous HCT.40 A subsequent analysis incorporating this cohort by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) included a total of 511 patients who relapsed after autologous HCT, of which 29% underwent allogeneic HCT.41 Factors that predicted poorer OS included early relapse (<6 months), stage IV, bulky disease, poor performance status, and a patient aged more than 50 years at relapse. Table 4 reviews the key studies evaluating the role of allogeneic HCT in Hodgkin lymphoma.

Summary of key studies evaluating the role of allogeneic HCT in Hodgkin lymphoma

| Study . | Type . | # of pts . | Prior AHSCT . | Donor type . | Conditioning . | PFS . | OS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42 | Retrospective registry (EBMT) | 168 | 52% | MSD 70%, MUD 30% | MAC 47%, RIC 53% | 20% MAC and 18% RIC at 5 y | 22% MAC and 28% RIC at 5 y |

| 43 | Single-center prospective | 58 | 83% | MSD 43%, MUD 57% | RIC 100% (fludarabine/ melphalan) | 32% at 2 y | 64% at 2 y |

| 44 | Retrospective registry (EBMT) | 285 | 80% | MSD 60%, MUD 33% | RIC/NMA 100% fludarabine based (79.5%), low-dose TBI (16%) | 25% at 3 y | 29% at 3 y |

| 45 | Retrospective registry (CIBMTR) | 143 | 89% | Unrelated 100% (matched in 77%) | RIC/NMA 100%, melphalan based 34% | 20% at 2 y | 37% at 2 y |

| 46 | Multicenter retrospective in France | 98 | 91% | Haplo 35%, MUD 28%, CB 37% | RIC/NMA 100% | 58% EFS at 3 y | 76% at 3 y Improved GRFS in Haplo |

| 47 | Retrospective registry (Japanese society for HCT) | 122 | 67% | MSD 39% MUD 17% | MAC 30%, RIC 62% | 31% | 66% at 3 y |

| 48 | Retrospective multicenter in Italy | 198 | 86% | MSD/MUD 67%, Haplo 33% | NMA 29%, RIC 51%, MAC 20% | Haplo 63%, MSD/MUD 29% at 2 y | 66% at 2 y |

| 12 | Retrospective registry (CIBMTR) | 596 | 80% | Haplo 24%, MSD 76% | NMA/RIC 100% | 34%-38% | 63% |

| 49 | Retrospective registry (EBMT) | 860 | MSD/MUD 64% Haplo 75% | 166 MSD/MUD, 694 Haplo | RIC 75%-80% | MSD/MUD 66%, Haplo 58% | MSD/MUD 82%, Haplo 70% Higher NRM in Haplo |

| Study . | Type . | # of pts . | Prior AHSCT . | Donor type . | Conditioning . | PFS . | OS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42 | Retrospective registry (EBMT) | 168 | 52% | MSD 70%, MUD 30% | MAC 47%, RIC 53% | 20% MAC and 18% RIC at 5 y | 22% MAC and 28% RIC at 5 y |

| 43 | Single-center prospective | 58 | 83% | MSD 43%, MUD 57% | RIC 100% (fludarabine/ melphalan) | 32% at 2 y | 64% at 2 y |

| 44 | Retrospective registry (EBMT) | 285 | 80% | MSD 60%, MUD 33% | RIC/NMA 100% fludarabine based (79.5%), low-dose TBI (16%) | 25% at 3 y | 29% at 3 y |

| 45 | Retrospective registry (CIBMTR) | 143 | 89% | Unrelated 100% (matched in 77%) | RIC/NMA 100%, melphalan based 34% | 20% at 2 y | 37% at 2 y |

| 46 | Multicenter retrospective in France | 98 | 91% | Haplo 35%, MUD 28%, CB 37% | RIC/NMA 100% | 58% EFS at 3 y | 76% at 3 y Improved GRFS in Haplo |

| 47 | Retrospective registry (Japanese society for HCT) | 122 | 67% | MSD 39% MUD 17% | MAC 30%, RIC 62% | 31% | 66% at 3 y |

| 48 | Retrospective multicenter in Italy | 198 | 86% | MSD/MUD 67%, Haplo 33% | NMA 29%, RIC 51%, MAC 20% | Haplo 63%, MSD/MUD 29% at 2 y | 66% at 2 y |

| 12 | Retrospective registry (CIBMTR) | 596 | 80% | Haplo 24%, MSD 76% | NMA/RIC 100% | 34%-38% | 63% |

| 49 | Retrospective registry (EBMT) | 860 | MSD/MUD 64% Haplo 75% | 166 MSD/MUD, 694 Haplo | RIC 75%-80% | MSD/MUD 66%, Haplo 58% | MSD/MUD 82%, Haplo 70% Higher NRM in Haplo |

AHSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant; CB, cord blood; Haplo, haploidentical donor; GRFS, GVHD free and relapse free survival; MSD, matched sibling donor; MUD, matched unrelated donor; NMA, nonmyeloablative; TBI, total-body irradiation.

Use of novel agents in the context of allogeneic HCT

Brentuximab vedotin

Prior studies have shown improved outcomes of allogeneic HCT in HL in the BV era.50 A single-center analysis of 72 patients with relapsed/refractory HL reported improved 3-year PFS (49%; 95% CI, 26%-68% vs 23%; 95% CI, 13%-35%; P = .02) and OS (84%; 95% CI, 57%-94% vs 50%; 95% CI, 36%-62%; P = .01) for patients treated from 2009 to 2013 compared with patients treated from 2000 to 2008. More patients in the recent era had received treatment with BV (60% vs 2%). However, a registry report from the EBMT that included 428 patients showed that prior BV did not directly affect OS after allogeneic HCT.51 Prior to undergoing allogeneic HCT, 210 patients received BV, compared to 218 who did not. In multivariate analysis, pre-HCT BV had no impact on acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), nonrelapse mortality (NRM), relapse, PFS, or OS but significantly reduced the risk of chronic GVHD (hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% CI 0.45-0.92; P < .02).

Checkpoint inhibitors

As CPIs become standard treatment for HL, there are concerns that prior CPIs may exacerbate allogeneic HCT complications, particularly GVHD, and lead to worse outcomes.6,52-55 Ijaz et al performed a systematic review that included 107 patients (93 with HL) who received CPI before and 176 patients (89 with HL) who received CPI after allogeneic HCT.52 In patients who received CPI prior to allogeneic HCT, acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, GVHD-related mortality risk, and an ORR were 56%, 29%, 11%, and 68%, respectively. The use of CPIs after allogeneic HCT was associated with incidences of acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, GVHD-related mortality risk, and an ORR of 14%, 9%, 7%, and 54%, respectively. Merryman et al reported 39 patients, including 31 with HL, who underwent allogeneic HCT after prior CPI.53 The 1-year OS and PFS were 89% (95% CI, 74-96) and 76% (95% CI, 56-87), respectively, whereas the 1-year cumulative incidences of relapse and NRM were 14% (95% CI, 4-29) and 11% (95% CI, 3-23), respectively. In a study of 44 patients who proceeded to allogeneic HCT after treatment with nivolumab, 6-month PFS and OS estimates were 82% and 87%, respectively.6 In a larger retrospective cohort of 209 patients with HL who underwent allogeneic HCT after CPI, the 2-year PFS and OS were 69% and 82%, respectively, while the 2-year cumulative incidences of relapse and NRM were 18% and 14%, respectively.54 In multivariable analyses, a longer interval from a CPI to allogeneic HCT was associated with a lower incidence of severe acute GVHD, and post-transplantation cyclophosphamide (PTCy)-based GVHD prophylaxis was associated with significant improvement in PFS. These results are markedly better than older Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) data, where PFS and OS were 30% and 56% at 1 year and 20% and 37% at 2 years, respectively.45 In a recent meta-analysis of 1850 patients receiving allogeneic HCT for relapsed HL, the pooled estimates for 3-year relapse-free survival (RFS) and OS were 31% (25-37) and 50% (41-58), respectively.56 In a meta-regression analysis, HCT in 2000 or later was associated with 5% to 10% lower NRM and relapse rates and 15% to 20% higher RFS and OS compared to earlier studies.

What is the preferred conditioning regimen for allogeneic HCT?

Historically, the use of myeloablative conditioning (MAC) has been associated with increased toxicity.57,58 A recent report from the EBMT, however, shows that in the modern era, survival may be similar with MAC and reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) but that MAC may provide better disease control.59 In contrast, reports from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and HL indicate that more intense regimens are in fact associated with worse outcomes.13,60 Currently, RIC remains the preferred conditioning intensity for adult patients with HL undergoing allogeneic HCT.13,43,44

Who is the better donor, and what is the preferred GVHD prophylaxis?

The preferred graft source remains somewhat controversial, with conflicting data in the literature.12,61,62 Some experts have even stated that haploidentical donors should be the preferred graft for allogeneic HCT in HL based on recent data showing improved OS compared to other graft sources.12,63,64 This recommendation would appear to conflict with recommendations for other diseases. It should be noted that recipients of haploidentical donors all receive PTCy and have been transplanted in the more recent era with a higher likelihood of prior CPI use in the case of HL. In this regard, a recent CIBMTR-EBMT study in patients with lymphoma who underwent allogeneic HCT with PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis showed decreased OS in recipients of haploidentical donors compared to matched unrelated donors (MUD).65 While further studies are needed to identify the preferred donor (matched vs haploidentical vs mismatched unrelated), we do not recommend the use of cord blood as a graft source given the known higher incidence of acute GVHD with this graft and concerns that the risks would rise even higher due to prior CPI exposure. Furthermore, there are currently no data on cord blood transplant in patients who have received a prior CPI. As far as GVHD prophylaxis, PTCy-based prophylaxis is now considered the standard of care across graft sources in RIC,66-68 and we definitely recommend it in a patient who has recently been treated with a CPI.

When should patients proceed to allogeneic HCT?

Prior to the introduction of effective novel therapies, the standard approach to patients with HL who relapsed after autologous HCT was to try and achieve a CR or at least a partial response and proceed with allogeneic HCT. With the introduction of CPIs, this treatment paradigm has evolved. While it is certainly a reasonable consideration to proceed with allogeneic HCT once CR has been achieved with CPIs, in many cases both the treating physician and the patient prefer to continue treatment with a CPI as long as the patient is responding and tolerating the treatment. This has the advantage of delaying or avoiding the potential complications and treatment-related mortality related to allogeneic HCT. This is true not only for older patients with comorbidities who would be at higher risk of treatment-related mortality but also for younger and fit patients. In our practice we recommend proceeding to allogeneic HCT for patients who do not respond to CPI, are intolerant of CPI, or progress on CPI. It is important, however, not to forget the potential curative benefit of allogeneic HCT in those patients and consider this approach over investigational agents or multiple lines of chemotherapy in patients no longer responding to CPIs.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient was treated with a combination of nivolumab and BV and initially tolerated the treatment without significant complications, achieving a CR. Regarding options for allogeneic HCT, a 22-year-old male MUD was identified in the registry. Her 34-year-old brother was haploidentical. After 12 cycles, the patient developed progressive neuropathy and BV was discontinued. She remained in CR. Six months later, a PET scan revealed recurrent small-volume disease that was confirmed on biopsy. At that time, the decision was made to proceed to allogeneic HCT using the MUD with conditioning of fludarabine and melphalan. GVHD prophylaxis consisted of PTCy, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Conclusions

The approvals of new and highly effective drugs such as BV and CPIs have resulted in lower numbers of patients with HL being referred for allogeneic HCT. Results in the recent era of novel agents, and CPIs in particular, have shown remarkable outcomes for allogeneic HCT in HL. This is driven by a lower incidence of relapse, suggesting the effects of the CPI on the donor immune system and the enhancement of graft-versus-lymphoma effects. These results continue to support allogeneic HCT as a viable treatment option for these patients. Several questions nevertheless remain open, including the donor source and timing of HCT.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (NIH/NIC; Support Grant P30 CA008748 (MAP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Miguel-Angel Perales: honoraria: Adicet, Allogene, Allovir, Caribou Biosciences, Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Equilium, Exevir, ImmPACT Bio, Incyte, Karyopharm, Kite/Gilead, Merck, Miltenyi Biotec, MorphoSys, Nektar Therapeutics, Novartis, Omeros, OrcaBio, Sanofi, Syncopation, VectivBio AG, and Vor Biopharma; data and safety monitoring board: Cidara Therapeutics, Sellas Life Sciences; advisory board: NexImmune; ownership interests: NexImmune, Omeros, OrcaBio: research funding: Allogene, Incyte, Kite/Gilead, Miltenyi Biotec, Nektar Therapeutics, Novartis.

Sairah Ahmed: research funding: Nektar, Merck, Xencor, Chimagen, Janssen, Kite/Gilead, Genmab; scientific advisory committee: Chimagen; data safety monitoring board: Myeloid Therapeutics; consultancy: ADC Therapeutics, KITE/Gilead.

Off-label drug use

Miguel-Angel Perales: Some of studies described include use of FDA approved drugs in lines of therapy that may have not yet been approved.

Sairah Ahmed: Some of studies described include use of FDA approved drugs in lines of therapy that may have not yet been approved.