Abstract

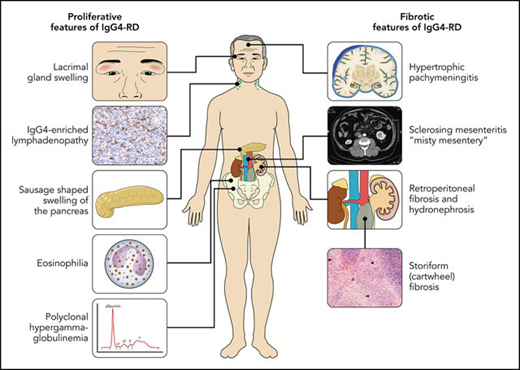

Immunoglobulin G4–related disease (IgG4-RD) is an immune-mediated disease with many important manifestations in hematopoietic and lymphoid tissue. IgG4 is the least naturally abundant IgG subclass, and the hallmark feature of IgG4-RD is markedly increased IgG4-positive plasma cells (with an IgG4 to IgG ratio >40%) in affected tissue, along with elevated polyclonal serum IgG and IgG4 in most patients. Histological diagnosis is essential, and other key features include storiform fibrosis, lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, tissue eosinophilia, and obliterative phlebitis. The disease can present with predominantly proliferative features, such as swollen lacrimal and salivary glands, orbital pseudotumor, autoimmune pancreatitis, polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (PHGG), eosinophilia, and tubulointerstitial nephritis of the kidneys, or predominantly fibrotic disease, including mediastinal and retroperitoneal fibrosis, sclerosing mesenteritis, and hypertrophic pachymeningitis. This review focuses on 4 key hematological manifestations: PHGG, IgG4-positive plasma cell enriched lymphadenopathy (LAD), eosinophilia, and retroperitoneal fibrosis (RPF). These features are found in 70%, 60%, 40%, and 25% of IgG4-RD patients, respectively, but can also represent key hematological “mimickers” of IgG4-RD, including Castleman disease (PHGG, LAD), eosinophilic vasculitis (eosinophilia, PHGG, LAD), hypereosinophilic syndromes (eosinophilia, LAD, PHGG), and histiocyte disorders (PHGG, LAD, RPF). An organized approach to these 4 manifestations, and how to distinguish IgG4-RD from its mimickers, is explained. Proliferative manifestations typically respond very well to treatment corticosteroids, rituximab, and other immunosuppressives, whereas chronic fibrotic disease may not be reversible with current treatment modalities.

Learning Objectives

Explain the key hematologic manifestations of IgG4-RD

Differentiate IgG4-RD from its key mimickers

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 66-year-old Chinese man is referred for chronic diffuse lymphadenopathy. He had autoimmune pancreatitis 2 years ago. The physical exam reveals symmetric swelling of the lacrimal and submandibular glands and palpable lymphadenopathy up to 2.5 cm in both cervical chains and axillae. Blood work shows an eosinophil count of 2.2 × 109/L (reference range, <0.7) with an otherwise normal complete blood count, a differential creatinine of 165 µmol/L (60-110), and a urine albumin to creatinine ratio of 25.5 (<3.1). IgG by nephelometry is 86.7 g/L (7-16). Serum protein electrophoresis shows an albumin level of 32.9 g/L and marked polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (PHGG) with beta gamma bridging (β2-globulins, 13.2 g/L, reference range, 1.8-4.8; γ-globulins, 71.2 g/L, reference range, 5.1-15). A lymph node biopsy performed 5 years earlier shows reactive follicular hyperplasia with polyclonal plasmacytosis, and a submandibular biopsy performed 7 years earlier shows sclerosing sialadenitis with fibrosis and a polyclonal infiltrate of eosinophils, plasma cells, and lymphocytes.

Introduction

Immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a disease of immune dysregulation characterized by the tumefactive (puffy) infiltration of affected organs, fibrosis, and IgG4-positive plasma cells in affected tissue.1-3 In 2001, increased serum IgG4 in patients with sclerosing (autoimmune) pancreatitis was discovered in Japan.4 Further examination of these patients revealed IgG4-positive plasma cells in the pancreas as well as in the extrapancreatic organs such as the bile duct, gastric mucosa, bone marrow, lymph nodes, and salivary glands, implying the presence of a systemic disease.5 Subsequently, many rare, eponymous entities such as Mikulicz syndrome (chronic swelling of the lacrimal and salivary glands), Ormond disease (idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis), and Reidel thyroiditis (fibrotic infiltration of the thyroid gland) were linked to IgG4. The unifying diagnosis for these diverse disease presentations was officially named “IgG4- Related Disease” at the first International Symposium in Boston in 2011.6 In 2022, IgG4-RD was included in the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms as a “tumor-like lesion with B cell predominance.”7

IgG4-RD has been labeled both “overdiagnosed,” in that increased IgG4-positive plasma cells and elevated serum IgG4 are present in many conditions that may mimic IgG4-RD, and “underdiagnosed,” as the disease can also be easily missed by physicians unfamiliar with its many manifestations.8 In October 2023, IgG4-RD received an ICD-10 code, D89.84, which falls under the range “diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism,” underscoring the important role hematologists can play in the diagnosis and management of these patients. The present review provides an overview of the disease and focuses on 4 key manifestations of IgG4-RD that are likely to present to hematologists: PHGG, IgG4-enriched lymphadenopathy, eosinophilia, and retroperitoneal fibrosis (RPF).

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

The point prevalence of IgG4-RD in the United States was 5.34 in 2019 and rising due to increased recognition.9 The median age of diagnosis is 55 to 60 years, and 60% to 65% of cases are in males, except for head and neck disease, wherein there is a slight female preponderance and a younger onset. The proliferative variant is more common in Asians, who also have higher serum IgG and IgG4 levels,10,11 whereas the fibrotic variant is more common in Whites.

The 4 subclasses of human IgG were discovered in myeloma serum samples in the 1960s.12 They are named in order of abundance; IgG4 myeloma composes only 2% of IgG myeloma cases, and the reference range for serum IgG4 is approximately 0.05 to 1.5 g/L in most laboratories.13 IgG4 is generally considered an anti-inflammatory antibody, as it has a low affinity for target antigens and is unable to bind Fcγ and C1q receptors.14 While diseases such as thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura and myasthenia gravis are mediated by IgG4 autoantibodies,15 the role of IgG4 in IgG4-RD itself requires further elucidation.16,17 Despite the prominence of IgG4-positive plasma cells in IgG4-RD, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells may play a more central role in the pathophysiology of the disease.18,19

Clinical presentation

Nearly any organ can be affected by this protean disease, and the most commonly affected organs are lymph nodes (60%), salivary and lacrimal glands (Mikulicz syndrome, 50%-75%), pancreatic-hepatobiliary (25%-30%), RPF (25%), and kidneys (15%-30%). Synovial tissue, brain parenchyma, bone (aside from eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis of the maxilla and facial bones), and skin are rarely involved, and extensive involvement of these organs should trigger a search for alternative or concomitant disease processes. Different “clusters,” or phenotypes, of IgG4-RD have been proposed (eg, pancreato-hepato-biliary disease, RPF and/or aortitis, head and neck limited disease, classic Mikulicz syndrome with systemic involvement),20 but the most practical way to divide the disease presentations is proliferative vs fibrotic disease (visual abstract and Table 1).21,22 Two-thirds of cases have a more proliferative phenotype, with features such as autoimmune pancreatitis, hepatobiliary involvement, lacrimal and salivary gland swelling, and tubulointerstitial nephritis. These are easier to diagnose as the involved organs, such as the lacrimal or salivary glands, are accessible for biopsy, and diagnostic biomarkers such as PHGG, serum IgG4, and IgE are more profoundly abnormal. The patient in Clinical Case 1 has classic proliferative disease, including swollen glands, autoimmune pancreatitis, and severe PHGG. One-third of patients have predominantly fibrotic disease, with features such as retroperitoneal and mediastinal fibrosis, thyroiditis, mesenteritis, and hypertrophic pachymeningitis. Fibrotic disease is often more morbid due to fibrotic stricture of the ureteric and biliary systems and other end organ damage that may not respond to systemic therapy. Proliferative and fibrotic disease are not entirely separate nor are they mutually exclusive. Patients may have features of both, and proliferative disease may progress to fibrosis. Regardless of the presentation, early recognition is essential to prevent organ damage from progressive diseases.

Features of proliferative vs fibrotic IgG4-RD

| . | Proliferative . | Fibrotic . |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Involvement of specific organs Symptoms are from tumefactive swelling of organs and organ dysfunction Chronic, relapsing and remitting | Involvement of body regions rather than distinct organs Contiguous spread and architectural distortion Progressive disease Chronic, long-standing disease (median time to diagnosis >6 months) |

| Organ involvement | Lacrimal and major salivary glands Lymph nodes Orbits and sinuses Lungs and airways Vasculature (aorta, coronary arteries) Pancreas and hepatobiliary system Kidneys | Retroperitoneum/aortitis Mediastinum Abdominal mesenteritis Thyroid Meninges |

| Laboratory | High serum IgG4 (especially Asian patients) Frequent elevation in IgE Eosinophilia Hypocomplementemia CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are low or modestly elevated in most cases | Normal or slightly elevated serum IgG4 and IgE Normal complement CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are low in most cases but elevated in the subset with active aortitis |

| Radiology | CT scan neck to pelvis sufficient for most If lacrimal swelling → CT head as well to assess for orbital involvement | For fibrotic disease, FDG-PET may be helpful to rule out histiocytosis (bone involvement) or lymphoma/metastatic cancer. FAPI-PET is an emerging tool for assessing fibrotic disease. |

| Pathology | Dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with many IgG4+ plasma cells Scattered eosinophils Storiform fibrosis Obliterative phlebitis rare | Scant lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with scattered IgG4+ plasma cells Storiform fibrosis predominant Obliterative phlebitis predominant |

| Treatment | Typically responsive to glucocorticoids and B-cell depletion | Glucocorticoids and B-cell depletion halt progression, but fibrosis is often not reversible. |

| . | Proliferative . | Fibrotic . |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Involvement of specific organs Symptoms are from tumefactive swelling of organs and organ dysfunction Chronic, relapsing and remitting | Involvement of body regions rather than distinct organs Contiguous spread and architectural distortion Progressive disease Chronic, long-standing disease (median time to diagnosis >6 months) |

| Organ involvement | Lacrimal and major salivary glands Lymph nodes Orbits and sinuses Lungs and airways Vasculature (aorta, coronary arteries) Pancreas and hepatobiliary system Kidneys | Retroperitoneum/aortitis Mediastinum Abdominal mesenteritis Thyroid Meninges |

| Laboratory | High serum IgG4 (especially Asian patients) Frequent elevation in IgE Eosinophilia Hypocomplementemia CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are low or modestly elevated in most cases | Normal or slightly elevated serum IgG4 and IgE Normal complement CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are low in most cases but elevated in the subset with active aortitis |

| Radiology | CT scan neck to pelvis sufficient for most If lacrimal swelling → CT head as well to assess for orbital involvement | For fibrotic disease, FDG-PET may be helpful to rule out histiocytosis (bone involvement) or lymphoma/metastatic cancer. FAPI-PET is an emerging tool for assessing fibrotic disease. |

| Pathology | Dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with many IgG4+ plasma cells Scattered eosinophils Storiform fibrosis Obliterative phlebitis rare | Scant lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with scattered IgG4+ plasma cells Storiform fibrosis predominant Obliterative phlebitis predominant |

| Treatment | Typically responsive to glucocorticoids and B-cell depletion | Glucocorticoids and B-cell depletion halt progression, but fibrosis is often not reversible. |

Diagnostic approach to suspected IgG4-related disease

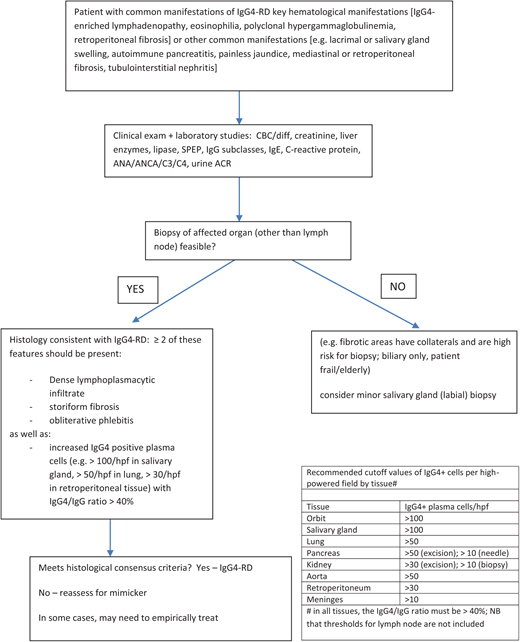

Most patients with suspected IgG4-RD are complex, and an efficient diagnostic approach is important. My approach is summarized in Figure 1 and hinges on 3 elements:

Awareness of the common manifestations of IgG4-RD and the differences between the proliferative and fibrotic phenotypes (Table 1)

Ability to recognize and assess the key manifestations referred to hematologists:

PHGG (present in 70% of IgG4-RD patients)

IgG4-positive plasma cell–enriched lymphadenopathy (60% of IgG4-RD patients)

Eosinophilia (40% of IgG4-RD patients)

RPF (25% of IgG4-RD patients). This includes being able to assess for diseases that mimic these manifestations of IgG4-RD and vice versa, such as Castleman disease (CD), vasculitis, hypereosinophilic syndromes, histiocyte disorders, and lymphoma (Table 2).

Understanding and applying the IgG4-RD diagnostic criteria. The International Consensus Criteria should be applied in patients in whom an adequate tissue sample is available.23 In patients for whom histological diagnosis is not safe or feasible, the 2019 ACR EULAR classification criteria can be a helpful diagnostic aide.24

Hematological and rheumatological mimickers of IgG4-RD

| Disease . | PHGG . | High serum IgG4 . | IgG4-enriched LAD . | Eosinophilia . | RPF . | High CRP . | Other overlap with IgG4-RD . | Contrasting features and notes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG4-RD—proliferative | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++ | + | Rare | N/A | Skin, synovium, bone, parenchymal brain involvement rare Autoantibodies negative or weak positive |

| IgG4-RD—fibrotic | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++++ | Typically low, but can be high in active aortitis | N/A | Skin, synovium, parenchymal brain involvement rare Nasal/facial bones can be involved in EAF but other bones are not involved Autoantibodies negative or weak positive |

| Multicentric CD (particularly iMCD-IPL) | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | ++++ | Albuminuria | Fever High CRP |

| Still’s disease | +++ | + | + | − | − | ++++ | Skin rash Synovitis Pleural/pericardial effusions Cardiomyositis | |

| Sjӧgren syndrome | ++ | ++ | + | + | − | Variable | Tubulointerstitial nephritis Sicca | Sicca more severe in Sjӧgren syndrome Strongly positive autoantibodies |

| Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome | ++++ | + | + | + | − | Rare | αβ double negative T cells FAS gene mutations Lymphocytosis Immune cytopenias | |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++++ | − | ++++ | Asthma Atopy High IgE | Cardiomyopathy/myocarditis Skin involvement |

| Lymphocyte-variant hypereosinophilic syndrome | + | + | + | ++++ | − | ++ | Asthma Atopy High IgE | Skin lesions in >90% of patients with L-HES |

| IgG4-secreting B-cell lymphoma | ++ (or monoclonal) | ++ | ++++ | + | + | ++ | Clonal B cells | |

| T-cell NHL (AITCL, HSTCL) | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++ | Clonal T cells | |

| Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | ++ | Autoimmune pancreatitis Hypertrophic pachymeningitis | Skin Bone Large histiocytes with emperipolesis MAPK mutations |

| Erdheim-Chester disease | ++ | + | ++ | − | ++ (hairy kidney) | +++ | Skin (xanthelasmas) Bone Large histiocytes BRAF in 50% | |

| Langerhan’s cell histiocytosis | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | Skin (xanthelasmas) Bone Liver CD1a+ histiocytes BRAF in 50% | |

| Sarcoidosis | ++ (PHGG or MGUS) | + | + | + | − | ++ | Pulmonary lesions | Uveitis Erythema nodosum High ACE level Noncaseating granuloma |

| Disease . | PHGG . | High serum IgG4 . | IgG4-enriched LAD . | Eosinophilia . | RPF . | High CRP . | Other overlap with IgG4-RD . | Contrasting features and notes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG4-RD—proliferative | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++ | + | Rare | N/A | Skin, synovium, bone, parenchymal brain involvement rare Autoantibodies negative or weak positive |

| IgG4-RD—fibrotic | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++++ | Typically low, but can be high in active aortitis | N/A | Skin, synovium, parenchymal brain involvement rare Nasal/facial bones can be involved in EAF but other bones are not involved Autoantibodies negative or weak positive |

| Multicentric CD (particularly iMCD-IPL) | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | ++++ | Albuminuria | Fever High CRP |

| Still’s disease | +++ | + | + | − | − | ++++ | Skin rash Synovitis Pleural/pericardial effusions Cardiomyositis | |

| Sjӧgren syndrome | ++ | ++ | + | + | − | Variable | Tubulointerstitial nephritis Sicca | Sicca more severe in Sjӧgren syndrome Strongly positive autoantibodies |

| Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome | ++++ | + | + | + | − | Rare | αβ double negative T cells FAS gene mutations Lymphocytosis Immune cytopenias | |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++++ | − | ++++ | Asthma Atopy High IgE | Cardiomyopathy/myocarditis Skin involvement |

| Lymphocyte-variant hypereosinophilic syndrome | + | + | + | ++++ | − | ++ | Asthma Atopy High IgE | Skin lesions in >90% of patients with L-HES |

| IgG4-secreting B-cell lymphoma | ++ (or monoclonal) | ++ | ++++ | + | + | ++ | Clonal B cells | |

| T-cell NHL (AITCL, HSTCL) | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++ | Clonal T cells | |

| Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | ++ | Autoimmune pancreatitis Hypertrophic pachymeningitis | Skin Bone Large histiocytes with emperipolesis MAPK mutations |

| Erdheim-Chester disease | ++ | + | ++ | − | ++ (hairy kidney) | +++ | Skin (xanthelasmas) Bone Large histiocytes BRAF in 50% | |

| Langerhan’s cell histiocytosis | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | Skin (xanthelasmas) Bone Liver CD1a+ histiocytes BRAF in 50% | |

| Sarcoidosis | ++ (PHGG or MGUS) | + | + | + | − | ++ | Pulmonary lesions | Uveitis Erythema nodosum High ACE level Noncaseating granuloma |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; AITCL, angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma; EAF, eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis; HSTCL, hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

The laboratory workup should include a complete blood count/ differential, creatinine, urine albumin to creatinine ratio (often elevated in patients with IgG4-renal disease), liver enzymes and lipase, serum protein electrophoresis, quantitative Igs, IgG subclasses, C-reactive protein (CRP; typically <30 mg/L), and complement levels. Most patients require computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis to examine for subclinical disease. “Sausage-shaped” swelling of the pancreas from IgG4-autoimmune pancreatitis, often with a hypoattenuating halo or capsule, when accompanied by wedge-shaped hypodensities in the kidneys (due to tubulointerstitial nephritis [TIN]), are nearly pathognomonic for IgG4-RD. The aorta and kidneys/ureters may be surrounded by a soft tissue rind when RPF is present. Those with clinical lacrimal gland swelling should also undergo a CT of the head to examine for orbital pseudotumor. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) will typically demonstrate modest FGD avidity and adds little to the CT in most cases of proliferative IgG4-RD. A diagnostic approach to the 4 key hematological features of IgG4-RD is summarized in the following sections.

Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia

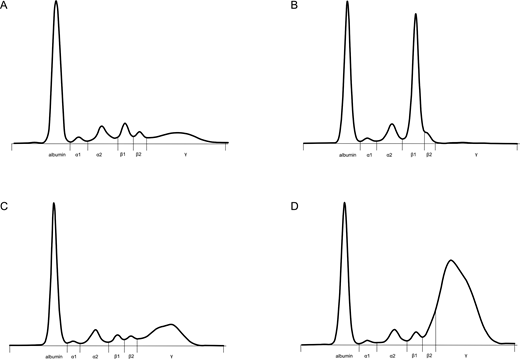

The patient in Clinical Case 1 has profound PHGG (Figure 2). Traditionally, PHGG has been viewed as a nonspecific reactive finding in patients with liver disease, autoimmunity, infection, and immunodeficiency25; however, PHGG can be a very helpful diagnostic clue in patients with complex systemic disease.26,27 Causes of polyclonal elevation of IgG can be separated into 8 categories: liver disease, autoimmune and autoinflammatory disease (including vasculitis), infection, hematological disorders (eg, CD, histiocytosis, lymphoma), nonhematological malignancy, immunodeficiency (eg, autoimmune lymphoproliferative disease), IgG4-RD, and iatrogenic (intravenous Ig [IVIG] administration). Then, after a careful history and physical exam focusing on these 8 categories, the differential diagnosis can be narrowed using the CRP and IgG subclass results (Table 3). In most reactive conditions, the IgG subclass is predominantly IgG1.14 CRP is low in IgG4-RD, typically less than 10 mg/L in most large cohort studies,28-30 except in cases of active aortitis/vasculitis or other concomitant infectious/inflammatory conditions.

Serum protein electrophoresis tracings. (A) Normal; (B) a 40-g/L monoclonal band running in the β1 region in a patient with IgG4 myeloma; (C) PHGG, predominantly IgG1, in a patient with Sjӧgren syndrome; (D) PHGG with beta-gamma bridging in a patient with IgG4-RD (Clinical Case 1). Figure courtesy of Eric Zhao and Andre Mattman.

Serum protein electrophoresis tracings. (A) Normal; (B) a 40-g/L monoclonal band running in the β1 region in a patient with IgG4 myeloma; (C) PHGG, predominantly IgG1, in a patient with Sjӧgren syndrome; (D) PHGG with beta-gamma bridging in a patient with IgG4-RD (Clinical Case 1). Figure courtesy of Eric Zhao and Andre Mattman.

Common causes of PHGG divided by CRP

| High CRP (>30 mg/L) . | Variable CRP . | Low CRP (<30 mg/L) . |

|---|---|---|

| • Infection • Malignancy • Vasculitis • Autoinflammatory • Hematologic (CD, ECD) Note: PHGG in these conditions is typically driven by IL-6 and other inflammatory cytokines. | • Autoimmune (Sjӧgren syndrome, sarcoidosis) • Iatrogenic (IVIG) • Hematologic (lymphoma, RDD) | • Liver disease • IgG4-RD • Immune deficiency (ALPS, dysgammaglobulinemias) • Graves disease Note: PHGG in these conditions is generally from immune dysregulation other than IL-6 signaling. In liver disease, loss of portal filtering and increased exposure to enteric antigens are implicated. |

| High CRP (>30 mg/L) . | Variable CRP . | Low CRP (<30 mg/L) . |

|---|---|---|

| • Infection • Malignancy • Vasculitis • Autoinflammatory • Hematologic (CD, ECD) Note: PHGG in these conditions is typically driven by IL-6 and other inflammatory cytokines. | • Autoimmune (Sjӧgren syndrome, sarcoidosis) • Iatrogenic (IVIG) • Hematologic (lymphoma, RDD) | • Liver disease • IgG4-RD • Immune deficiency (ALPS, dysgammaglobulinemias) • Graves disease Note: PHGG in these conditions is generally from immune dysregulation other than IL-6 signaling. In liver disease, loss of portal filtering and increased exposure to enteric antigens are implicated. |

CRP is a surrogate for systemic inflammation and is the “rule of thumb” with many individual exceptions. For example, a patient with an inflammatory condition may have received corticosteroids suppressing their CRP, or a patient with a condition such as IgG4-RD may have a concomitant infection driving up the CRP.

ALPS, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome.

PHGG is present in about 70% of patients with IgG4-RD, and rare cases of polyclonal hyperviscosity have been reported.31,32 Most laboratories use immunonephelometry or chemiluminescence for IgG subclass measurement, but very high IgG4 levels may be prone to the hook effect. Mass spectrometry is an alternative option that avoids the hook effect and the formation of immune complexes.33 Mild elevation in serum IgG4 is very nonspecific and is often seen in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Serum IgG4 levels above 5 g/L are about 90% specific for IgG4-RD, but importantly, markedly elevated levels can be seen in CD, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), adult onset Still disease, Sjӧgren syndrome, and many other diseases, so clinicopathological correlation is essential.14

CLINICAL CASE 1 (continued)

Further investigations demonstrate CRP, 1.6 mg/L (<3.1) and IgG subclasses IgG1, 36.3 g/L (2.8-8); IgG2, 3.41 g/L (1.1-5.7); IgG3, 19.7 g/L (0.5-1.25); IgG4, 31.4 g/L (0.05-1.25). C3 is 0.31 (0.8-1.8); C4 is less than 0.02 (0.12-0.36), and antinuclear antibody and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody are negative. Although IgG1, IgG3, and IgG4 are all elevated, IgG4 is most markedly abnormal. The normal CRP, negative antinuclear antibody and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and hypocomplementemia are typical for IgG4-RD. He should undergo a CT of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis. A histological diagnosis of IgG4-RD should be sought. His previous lymph node specimen is reviewed and demonstrates follicular hyperplasia, a polyclonal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, and progressive transformation of germinal centers.

IgG4-enriched lymphadenopathy and other histological considerations

Understanding the histological features of IgG4-RD laid out by the International Consensus Criteria is crucial for diagnosis of this disease (Figure 1).23 The presence of IgG4-positive plasma cells in a tissue sample is simply one feature of the disease. Importantly, the number of IgG4-positive cells should meet the minimum threshold for the given type of biopsy (>50 cells/high-powered field (HPF) for excisional biopsy in most tissues) with an IgG4/IgG ratio greater than 40%, and 2 or more of the following features must also be present: dense (polyclonal) lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, storiform (swirling or cartwheel pattern) fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis.

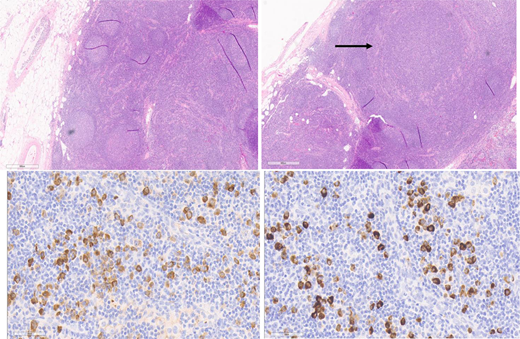

The bone marrow and lymph nodes are lower yield than other tissues for diagnosis. Although the seminal report of IgG4-RD in 2003 included 2 cases with bone marrow involvement,5 the presence of increased IgG4-positive plasma cells is rare and the specificity unknown. In most tissues the histological appearance is fairly uniform, but 2 notable exceptions are the kidneys and lymph nodes. Renal IgG4-RD manifests as TIN in 80% of cases, membranous nephropathy in 20%, and, rarely, as other histology such as acute interstitial nephritis.34 Lymph node pathology is complicated by the fact that at least 5 histological patterns of IgG4-lymphadenopathy (IgG4-LAD) are recognized35: 1) CD like, 2) follicular hyperplasia pattern, 3) progressive transformation of germinal center (PTGC) [Figure 3], 4) interfollicular expansion pattern, and 5) inflammatory pseudotumor pattern. Moreover, in many diseases such as CD, Kimura disease, EGPA, and Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes (RDD) disease, [Figure 4] a subset of patients have increased IgG4-positive plasma cells in the lymph nodes.36-40 Thus, if lymph node histology is the only available tissue, extreme care must be taken to have an expert pathologist experienced in IgG4-RD and its mimickers review the specimen.

Excisional axillary lymph node biopsy from a patient with IgG4-RD with a PTGC pattern of IgG4-LAD. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, top left and right 2 images at 4 × magnification. Top left: The lymph node shows follicular hyperplasia with progressive transformation of germinal centers. Top right: There is a notable absence of obliterative phlebitis and capsular and storiform fibrosis. Bottom left: IgG stain. Bottom right: IgG4 stain. Hot spots show more than 100 IgG4-positive cells per high-powered field, and the IgG4 to IgG ratio is higher than 40%. Figure courtesy of Collin Pryma.

Excisional axillary lymph node biopsy from a patient with IgG4-RD with a PTGC pattern of IgG4-LAD. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, top left and right 2 images at 4 × magnification. Top left: The lymph node shows follicular hyperplasia with progressive transformation of germinal centers. Top right: There is a notable absence of obliterative phlebitis and capsular and storiform fibrosis. Bottom left: IgG stain. Bottom right: IgG4 stain. Hot spots show more than 100 IgG4-positive cells per high-powered field, and the IgG4 to IgG ratio is higher than 40%. Figure courtesy of Collin Pryma.

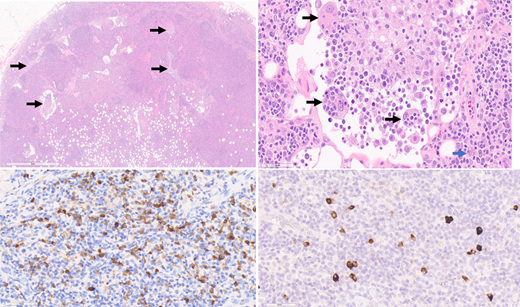

RDD LAD with increased IgG4+ plasma cells. Top left: H&E, 2 × magnification. Left axillary lymph node biopsy from a patient with RDD disease. The lymph node architecture is preserved, but there are distended sinuses with lesional histiocytes (top left image, arrows). Top right: H&E, 40 × magnification. Histiocytes with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei containing prominent nucleoli characterize the lesion. Many contain engulfed inflammatory cells (emperipolesis), such as those labeled with a black arrow. Occasional background plasma cells are identified (blue arrow). Bottom left: IgG immunohistochemical stain, 40 × magnification. The higher magnification of Figure 4 highlights the many plasma cells positive for IgG. Bottom right: IgG4 immunohistochemical stain, 40 × magnification. The higher magnification of Figure 4 highlights the scattered plasma cells positive for IgG4. The IgG4/IgG ratio is not increased (14%). Figure courtesy of Collin Pryma.

RDD LAD with increased IgG4+ plasma cells. Top left: H&E, 2 × magnification. Left axillary lymph node biopsy from a patient with RDD disease. The lymph node architecture is preserved, but there are distended sinuses with lesional histiocytes (top left image, arrows). Top right: H&E, 40 × magnification. Histiocytes with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei containing prominent nucleoli characterize the lesion. Many contain engulfed inflammatory cells (emperipolesis), such as those labeled with a black arrow. Occasional background plasma cells are identified (blue arrow). Bottom left: IgG immunohistochemical stain, 40 × magnification. The higher magnification of Figure 4 highlights the many plasma cells positive for IgG. Bottom right: IgG4 immunohistochemical stain, 40 × magnification. The higher magnification of Figure 4 highlights the scattered plasma cells positive for IgG4. The IgG4/IgG ratio is not increased (14%). Figure courtesy of Collin Pryma.

Clinicopathological correction is critical (Table 2). For example, an entity known as idiopathic plasmacytic lymphadenopathy, characterized by polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, chronic inflammation, and IgG4-enriched lymphadenopathy, has recently been classified as a subtype of idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD-IPL).41 In a seminal comparative study of iMCD-IPL and IgG4-RD, 13 of 39 patients with iMCD-IPL met histological criteria for IgG4-LAD (>100/HPF and IgG4 to IgG ratio >40%), and these patients also had serum IgG4 levels of 5 g/L or higher.42 However, the median CRP in the iMCD patients was 61 mg/L compared to 1 mg/L in the IgG4-RD patients (P < .001), demonstrating how simple laboratory parameters such as CRP can help differentiate between these rare, distinct conditions.

CLINICAL CASE 1 (continued)

IgG4 and IgG staining revealed hot spots of higher than 100 IgG4-positive plasma cells/HPF and a PTGC pattern. The submandibular gland biopsy is also reviewed and shows storiform fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis, and IgG4 cells at 150/HPF with an IgG4 to IgG ratio of 80%. The diagnosis of IgG4-RD is confirmed. He receives 2 doses of 1 g rituximab IV every 2 weeks followed by maintenance prednisone at 5 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil at 500 mg twice daily and attains an excellent clinical, radiological, and biochemical response, with normalization of renal function and serum IgG4 levels to 1.5 to 2 g/L.

Eosinophilia

Approximately 40% of patients with IgG4-RD present with eosinophilia, but this is rarely higher than 3 × 109/L and is often evanescent, ablating with steroids or other treatment.24,43 Some IgG4-RD patients may mimic lymphocyte-variant hypereosinophilic syndrome (L-HES) in that the T-cell immunophenotype may be abnormal (CD4+/CD3−, CD4+/CD7−, and “double negative” T cells), and T-cell clonality by PCR may be positive, presumably due to the oligoclonal T-cell expansions seen in IgG4-RD. Asthma, allergy, lymphadenopathy, and elevated IgE are common in both IgG4-RD and L-HES. However, the eosinophilia in L-HES is typically more severe (>5 × 109/L) and persistent and is typically associated with extensive cutaneous disease, which is rare in IgG4-RD.44 Eosinophilic vasculitis, particularly EGPA, is an important mimicker, as serum IgG4 levels can be markedly elevated, and IgG4-positive plasma cells can infiltrate affected tissues.37 Likewise, secondary eosinophilia from inflammatory bowel disease may mimic eosinophilic IgG4-RD, but both in EGPA and inflammatory bowel disease the CRP is typically elevated to more than 30 mg/L (Table 2).

CLINICAL CASE 1 (continued)

This patient had flow cytometry of peripheral blood sent at initial workup because of the eosinophilia. He has a small population of T cells with aberrant loss of CD7, and his T cell clonality by PCR is reported as clonal. These are nonspecific findings sometimes seen in IgG4-RD.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 78-year-old White man presents with back and abdominal pain and is found to have perivascular soft tissue thickening around the descending aorta and both kidneys. He has a history of chronic sclerosing cholangitis. His lab results are as follows: eosinophils, 0.3; IgE, 99 μg/L (<430); CRP, 3 mg/L; serum protein electrophoresis, normal; gamma globulins, 8 g/L; IgG, 8.4 g/L; IgG4, 0.8 g/L.

Retroperitoneal fibrosis

Approximately one-third of patients with IgG4-RD present with fibrotic disease, and RPF is the most common manifestation. RPF can be caused by drugs (eg, methyldopa, β-blockers), infections (eg, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis), or radiotherapy or surgical intervention in the retroperitoneum. Historically, idiopathic RPF was called Ormond disease, but the majority of patients with Ormond disease in fact have fibrotic IgG4-RD.45 Sclerosing cholangitis is frequent in fibrotic IgG4-RD and can also be seen in Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) and CD.

Important hematological causes of RPF include lymphoma and histiocyte disorders, including (ECD) and RDD disease.39 The RPF of ECD is often characterized by wispy projections on CT, also known as “hairy kidney.” Importantly, like IgG4-RD, ECD can demonstrate fibrosis and even storiform fibrosis in extranodal tissues. Both ECD and RDD can be notoriously difficult to diagnose in extranodal tissues, as the characteristic histiocytes (foamy histiocytes and Touton giant cells in ECD; large histiocytes with pale cytoplasm and frequent emperipolesis in RDD) are rarer, and fibrosis and inflammatory infiltrates are more prominent.

One of the challenges of fibrotic IgG4-RD is that noninvasive biomarkers such as IgG, IgG4, and eosinophils are normal at baseline, and the imaging of affected organs along with endoscopy or other direct visualization is necessary. While FDG-PET has limited value in proliferative IgG4-RD, scanning with tracers specific for fibroblast activation protein (FAPI) shows promise for staging and monitoring fibrotic IgG4-RD. In a study of 27 patients, 68Ga-FAPI-04 PET correlated well with activated fibroblasts expressing FAP.46 However, this modality is not clinically available in most centers.

CLINICAL CASE 2 (continued)

A core needle biopsy of the RPF reveals a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, obliterative phlebitis, and up to 20 IgG4- positive plasma cells/HPF with an IgG4 to IgG ratio of 50%. He is diagnosed with IgG4-RD and receives 2 doses of rituximab IV at 1 g every 2 weeks. A posttreatment CT scan shows partial reduction in the volume of the periaortic soft tissue rind.

Treatment and future directions

Most patients with proliferative disease respond to corticosteroids, and in fact steroid response is a component of the HiSort diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis.47 However, over 40% of patients develop new or worsening diabetes due to corticosteroids. B-cell depletion with rituximab at 2 doses of 1 g IV every 2 weeks is highly effective in more than 90% of patients, particularly those with proliferative disease.48 However, most patients need retreatment within 2 years if rituximab is used as a single agent, and medication coverage is challenging in many jurisdictions outside the United States. Other immunosuppressives such as azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil have reported response rates of 40% to 50% and can be useful for maintenance of remission.49 In rare cases of refractory disease, lymphoma chemotherapy regimens such as bendamustine and rituximab may be helpful in ablating the T cells and B cells responsible for disease.32

Novel agents such as dupilumab (interleukin [IL]-4/13 inhibitor), rilzabrutinib (Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor), abatacept (T-cell inhibitor), inebilizumab, and obexelimab (CD19-directed B-cell depletion) have shown promise in case series and single-arm prospective trials.50-53 Larger randomized trials of these agents and others are underway. Not surprisingly, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that patients receiving maintenance rituximab at fixed intervals had a lower risk of disease flare than those receiving it “on demand.”54 Better biomarkers are needed to select patients for maintenance; the measurement of CD19+ B-cell depletion and persistence of T-follicular helper cells after rituximab shows promise in this regard.55 Developing more effective therapies for fibrotic disease is a priority, and the inclusion of patient-centered outcomes will be an important dimension for IgG4-RD trials and studies.

Acknowledgment

Luke Y. C. Chen's research is supported by a philanthropic gift from the Hsu & Taylor Family through the University of British Columbia and Vancouver General Hospital Foundation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Luke Y. C. Chen: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Luke Y. C. Chen: Off-label use of rituximab is discussed in this review.