Abstract

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) are a heterogeneous category of disease entities occurring in the context of iatrogenic immune suppression. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–driven B-cell lymphoproliferation represents the prototype of quintessential PTLD, which includes a range of histologies named nondestructive, polymorphic, and monomorphic EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) PTLD. While EBV is associated with the majority of PTLD cases, other drivers of lymphoid neoplasia and lymphoma transformation can occur—with or without EBV as a codriver—thus underlining its vast heterogeneity. In this review, we discuss the evolution in contemporary PTLD nomenclature and its emphasis on more precise subcategorization, with a focus on solid organ transplants in children, adolescents, and young adults. We highlight the fact that patients with quintessential EBV-associated PTLD—including those with monomorphic DLBCL—can be cured with low-intensity therapeutic approaches such as reduction in immune suppression, surgical resection, rituximab monotherapy, or rituximab plus low-dose chemotherapy. There is, though, a subset of patients (approximately 30%-40%) with quintessential PTLD that remains refractory to lower-intensity approaches, for whom intensive, lymphoma-specific chemotherapy regimens are required. Other forms of monomorphic PTLD, which are as diverse as the spectrum of defined lymphoma entities that also occur in immunocompetent patients, are rarely cured with lower-intensity therapies and appear to be better categorized as posttransplant lymphomas. These distinct scenarios represent the variations in lymphoid pathology that make up a conceptual framework for PTLD consisting of lymphoid hyperplasia, neoplasia, and malignancy. This framework serves as the basis to inform risk stratification and determination of evidence-based treatment strategies.

Learning Objectives

Differentiate the various histologies that fall under the PTLD umbrella and explain their relationship with EBV

Evaluate and review evidence that informs management of these complex disorders

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) are commonly lumped together as an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–driven lymphoproliferative phenomenon occurring in the setting of iatrogenic immune suppression following hematopoietic or solid organ transplant (SOT). This is understandable, as PTLD—especially in the pediatric population—is typically associated with EBV and its epidemiological incidence is greatest in patients who are EBV naïve at time of transplant (Table 1).1-6 However, somatic alterations may also combine with EBV as drivers of lymphoproliferation and lymphomagenesis, and indeed, there are cases of EBV-negative (EBV−) PTLD.7 In discussing PTLD, it is necessary to recognize the heterogeneity of this spectrum of disorders and to approach each distinct disease separately to understand differences in presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival. This article highlights the nuances that differentiate the various histologies that fall under the PTLD umbrella and reviews the evidence that informs management. Although we focus on PTLD developing after SOT in children and young adults, many of the concepts are translatable to PTLD in other settings.

Incidence of PTLD among pediatric solid organ transplant recipients at 5 years posttransplant

| Organ type . | EBV negative . | EBV positive . |

|---|---|---|

| Kidney | 2-2.5% | ~1% |

| Liver | ~5% | 2-3% |

| Heart | 6-7% | 3-4% |

| Lung | 7-8% | 2-3% |

| Intestinea | ~10% | 4-5% |

| Organ type . | EBV negative . | EBV positive . |

|---|---|---|

| Kidney | 2-2.5% | ~1% |

| Liver | ~5% | 2-3% |

| Heart | 6-7% | 3-4% |

| Lung | 7-8% | 2-3% |

| Intestinea | ~10% | 4-5% |

Data reported based on EBV status of recipient at time of and are derived from the United States Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network & Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients 2022 Annual Data Report transplant.

Data are from combined adult and pediatric intestine transplants.

Historically, PTLD has been classified based on morphological features and subcategorized broadly as early lesion, polymorphic, monomorphic, and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) PTLD.8,9 It was common to dichotomize this classification system as a spectrum with early lesion and polymorphic PTLD on one end and monomorphic and HL PTLD on the other.10 Such dichotomy did not differentiate that early lesion PTLD is characterized as lymphoid hyperplasia while polymorphic PTLD typically represents monoclonal proliferation and lymphoid neoplasia. This classification also failed to highlight that monomorphic PTLD with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) histology (the most common monomorphic form) may be more similar to polymorphic PTLD than de novo DLBCL occurring in immunocompetent children.7 In contrast, monomorphic PTLD with Burkitt lymphoma (BL) histology is very similar to de novo BL.7 Finally, earlier classification systems failed to distinguish the subset of EBV− PTLD, which while less common represents different disease pathophysiology.11 To address these limitations, PTLD nomenclature has evolved over the past 2 decades, and both the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Consensus Classification (ICC) 2022 classification systems have implemented changes to categorize patients more precisely (Table 2).12-15 For consistency and brevity in this review, we generally use the ICC 2022 nomenclature, referring to WHO 2022 nomenclature where relevant.14,15

Evolution of PTLD nomenclature

| Classification system . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO 2008 . | WHO 2016 . | WHO 2022 . | ICC 2022 . |

| Early lesions PTLD | Early lesions PTLD | Hyperplasias, EBV +/−, post SOT | Nondestructive PTLD |

| Plasmacytic hyperplasia PTLD | Plasmacytic hyperplasia PTLD | Plasma cell hyperplasia | Plasmacytic hyperplasia PTLD |

| Infectious mononucleosis-like PTLD | Infectious mononucleosis PTLD | Mononucleosis-like hyperplasia | Infectious mononucleosis PTLD |

| N/A | Florid follicular hyperplasia PTLD | Follicular hyperplasia | Florid follicular hyperplasia PTLD |

| Polymorphic PTLD | Polymorphic PTLD | Polymorphic LPDa | Polymorphic PTLD |

| Monomorphic PTLD | Monomorphic PTLD | Lymphoma, EBV +/−, post SOT | Monomorphic PTLD |

| Classical Hodgkin PTLD | Classical Hodgkin PTLD | Classic Hodgkin PTLD | |

| Classification system . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO 2008 . | WHO 2016 . | WHO 2022 . | ICC 2022 . |

| Early lesions PTLD | Early lesions PTLD | Hyperplasias, EBV +/−, post SOT | Nondestructive PTLD |

| Plasmacytic hyperplasia PTLD | Plasmacytic hyperplasia PTLD | Plasma cell hyperplasia | Plasmacytic hyperplasia PTLD |

| Infectious mononucleosis-like PTLD | Infectious mononucleosis PTLD | Mononucleosis-like hyperplasia | Infectious mononucleosis PTLD |

| N/A | Florid follicular hyperplasia PTLD | Follicular hyperplasia | Florid follicular hyperplasia PTLD |

| Polymorphic PTLD | Polymorphic PTLD | Polymorphic LPDa | Polymorphic PTLD |

| Monomorphic PTLD | Monomorphic PTLD | Lymphoma, EBV +/−, post SOT | Monomorphic PTLD |

| Classical Hodgkin PTLD | Classical Hodgkin PTLD | Classic Hodgkin PTLD | |

LPD, lymphoproliferative disorder.

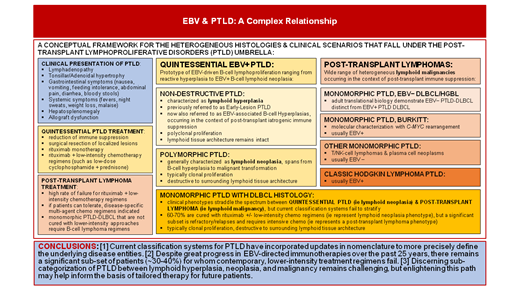

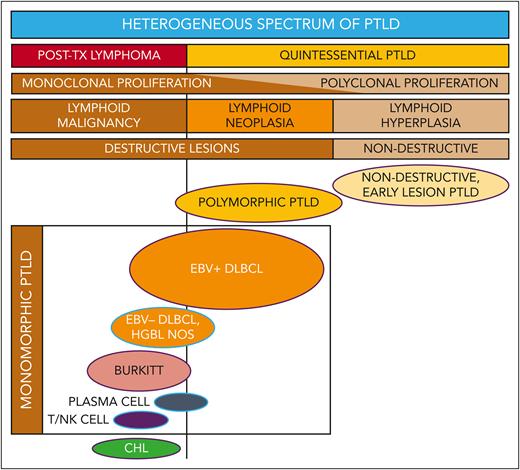

We prefer to conceptualize PTLD as a spectrum characterized by 3 variations of lymphoproliferation: lymphoid hyperplasia, neoplasia, and malignancy (Figure 1). Whether these represent a continuum of phases or an individual predisposition to 1 form vs another is a subject of debate. Regardless, clinicians should be aware that there are both critical distinctions and confounding overlap in the clinical presentations and therapeutic strategies for the various lymphoproliferative processes categorized as PTLD.

Reconceptualizing the framework for categorizing the heterogeneous spectrum of lymphoproliferation in pediatric posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD). Traditional PTLD classification is based on morphological features stratified as nondestructive, polymorphic, monomorphic, and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) PTLD. This revised stratification highlights the heterogeneity of monomorphic PTLD and demarcates a threshold beyond which quintessential EBV-driven lymphoid hyperplasia/neoplasia transforms into malignant lymphoma. EBV+ DLBCL in particular straddles the threshold between quintessential PTLD and posttransplant lymphoma. HGBL NOS, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified and other gray-zone, Burkitt-like mature B-cell lymphomas; PLASMA CELL, plasma cell neoplasm; T/NK CELL, T/NK-cell lymphoma; TX, transplant. Ovals with purple borders indicate entities that are typically EBV positive; ovals with blue borders indicate entities that are often EBV negative. Reproduced from El-Mallawany and Kamdar20 with permission.

Reconceptualizing the framework for categorizing the heterogeneous spectrum of lymphoproliferation in pediatric posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD). Traditional PTLD classification is based on morphological features stratified as nondestructive, polymorphic, monomorphic, and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) PTLD. This revised stratification highlights the heterogeneity of monomorphic PTLD and demarcates a threshold beyond which quintessential EBV-driven lymphoid hyperplasia/neoplasia transforms into malignant lymphoma. EBV+ DLBCL in particular straddles the threshold between quintessential PTLD and posttransplant lymphoma. HGBL NOS, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified and other gray-zone, Burkitt-like mature B-cell lymphomas; PLASMA CELL, plasma cell neoplasm; T/NK CELL, T/NK-cell lymphoma; TX, transplant. Ovals with purple borders indicate entities that are typically EBV positive; ovals with blue borders indicate entities that are often EBV negative. Reproduced from El-Mallawany and Kamdar20 with permission.

Quintessential PTLD

In this article, we refer to the prototypical spectrum of post-transplant EBV-driven lymphoproliferation as quintessential PTLD, defined as lymphoid hyperplasia or neoplasia driven by lytic EBV activation in immunocompromised patients. Quintessential PTLD includes EBV-positive (EBV+) nondestructive PTLD (plasmacytic hyperplasia, florid follicular hyperplasia, infectious mononucleosis), EBV+ polymorphic PTLD, and EBV+ monomorphic PTLD with DLBCL histology (Table 3). These entities may be successfully treated with EBV-directed therapeutics such as reduction of iatrogenic immune suppression (RIS), anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (anti-CD20 moAb, ie, rituximab) monotherapy, or anti-CD20 moAb plus low-dose chemotherapy. Surgical resection of lymphoproliferative lesions has also been successful.

Categorizing the heterogeneous spectrum of PTLD

| Framework . | Original category . | Infiltrative patterna . | Histology . | Typical therapy . | EBV association . | Think of as . . . . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-transplant EBV | EBV viremia | None | Not applicable (no lesions present, therefore no biopsy) | RI and clinical observation | Always | Asymptomatic posttransplant EBV infection |

| Quintessential PTLD | Early lesion | Nondestructive | Plasmacytic hyperplasia | Most likely to respond to RIS or surgical resection | Virtually always EBV+ | EBV-driven reactive lymphoid hyperplasia |

| Infectious mononucleosis-like | ||||||

| Florid follicular hyperplasia | ||||||

| Polymorphic | Destructive | Polymorphous infiltrate with various stages of B-cell maturation, often clonal | May respond to RIS, but often requires rituximab or CPRb | Typically EBV+ (>95%) | Lymphoid neoplasia | |

| Monomorphic | Destructive | DLBCL | Low-dose CPR. Potentially, up to 50% respond to rituximab alone. | Quintessential cases are typically EBV+ | Lymphoid neoplasia | |

| Post-transplant NHL | Monomorphic | Destructive | DLBCL | Multiagent chemotherapy for mature B-NHL | EBV− potential red flag Refractory EBV+ cases | De novo lymphoma in an immunocompromised patient |

| Post-transplant NHL | Monomorphic | Destructive | Burkitt lymphoma | Require disease-specific multi-agent chemotherapy | Burkitt usually EBV+ Others often EBV− | De novo lymphoma in an immunocompromised patient |

| High-grade B-cell lymphoma | ||||||

| T/NK-cell lymphoma | ||||||

| Plasma cell neoplasm | ||||||

| Post-transplant HL | Hodgkin lymphoma | Destructive | Classic Hodgkin lymphoma | Requires disease-specific multiagent chemotherapy | Usually EBV+ (>75%) | De novo lymphoma in an immunocompromised patient |

| Framework . | Original category . | Infiltrative patterna . | Histology . | Typical therapy . | EBV association . | Think of as . . . . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-transplant EBV | EBV viremia | None | Not applicable (no lesions present, therefore no biopsy) | RI and clinical observation | Always | Asymptomatic posttransplant EBV infection |

| Quintessential PTLD | Early lesion | Nondestructive | Plasmacytic hyperplasia | Most likely to respond to RIS or surgical resection | Virtually always EBV+ | EBV-driven reactive lymphoid hyperplasia |

| Infectious mononucleosis-like | ||||||

| Florid follicular hyperplasia | ||||||

| Polymorphic | Destructive | Polymorphous infiltrate with various stages of B-cell maturation, often clonal | May respond to RIS, but often requires rituximab or CPRb | Typically EBV+ (>95%) | Lymphoid neoplasia | |

| Monomorphic | Destructive | DLBCL | Low-dose CPR. Potentially, up to 50% respond to rituximab alone. | Quintessential cases are typically EBV+ | Lymphoid neoplasia | |

| Post-transplant NHL | Monomorphic | Destructive | DLBCL | Multiagent chemotherapy for mature B-NHL | EBV− potential red flag Refractory EBV+ cases | De novo lymphoma in an immunocompromised patient |

| Post-transplant NHL | Monomorphic | Destructive | Burkitt lymphoma | Require disease-specific multi-agent chemotherapy | Burkitt usually EBV+ Others often EBV− | De novo lymphoma in an immunocompromised patient |

| High-grade B-cell lymphoma | ||||||

| T/NK-cell lymphoma | ||||||

| Plasma cell neoplasm | ||||||

| Post-transplant HL | Hodgkin lymphoma | Destructive | Classic Hodgkin lymphoma | Requires disease-specific multiagent chemotherapy | Usually EBV+ (>75%) | De novo lymphoma in an immunocompromised patient |

Infiltrative pattern refers to the morphology of the lymphocytic hyperplasia and/or infiltrate observed on tissue biopsy.

Those patients who do not achieve CR with CPR will likely require mature B-cell NHL intensive multiagent chemotherapy.

CPR, low-dose cyclophosphamide, prednisone, and rituximab regimen; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; RIS, reduction in immune suppression.

In contrast, we categorize patients with other forms of monomorphic PTLD and those with EBV− disease as post-transplant lymphomas based on the WHO 2022 classification system (Figure 1). The following clinical cases highlight these concepts.

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 2-year-old boy underwent a heart transplant at the age of 7 months from an EBV− donor. Sixteen months after the transplant, he developed upper airway obstruction and severe sleep apnea. He was otherwise well, without lymphadenopathy, systemic or gastrointestinal symptoms, and no signs of allograft rejection.

EBV viral load (VL) first became detectable 2 months prior at 2195 IU/mL, followed by a logarithmic increase to 122 042 IU/mL 1 month later, at which time his immune suppression was reduced. Since then, EBV VL fluctuated between 30 000 and 80 000 IU/mL.

He underwent tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy, and hematopathology evaluation revealed florid follicular hyperplasia with numerous reactive follicles of varying shapes and sizes. CD20 stains highlighted follicular and parafollicular B lymphocytes, and EBV Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNAs in situ hybridization highlighted the hyperplastic lesions. He was diagnosed with nondestructive florid follicular hyperplasia PTLD. No other suspicious sites were identified on imaging. His symptoms resolved, and adjustments to immunosuppression resulted in low-level EBV viremia ranging between 1000 and 20 000 IU/mL. He did not receive additional treatment beyond surgical resection and RIS and had no recurrence of PTLD.

Nondestructive PTLD

Previously referred to as early lesion PTLD, ICC 2022 refers to this entity as nondestructive PTLD while the WHO 2022 classification uses the term hyperplasia to highlight this EBV-driven reactive B-cell hyperplasia. Nondestructive PTLD is virtually always EBV+, with rare cases of florid follicular hyperplasia PTLD reported as EBV−.16 Symptoms are attributed to lymphoid hyperplasia, most commonly as tonsillar and/or adenoidal hypertrophy, though gastrointestinal involvement and lymphadenopathy also occur.17 Nondestructive PTLD is characteristically polyclonal and does not represent neoplastic transformation.13 Most patients are successfully treated with RIS and/or surgical resection.17,18 However, patients at risk of transplant rejection who cannot afford RIS can be effectively treated with rituximab. Beyond nondestructive PTLD, the remainder of lymphoproliferative entities discussed are more severe and represent either lymphoid neoplasia or malignancy.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 19-year-old woman (EBV naïve with an EBV+ donor) presented 7 months after a lung transplant with persistent abdominal pain and severe oral intolerance. Computed tomography and fluorodeoxyglucose on positron emission tomography demonstrated multifocal bowel wall thickening and intense hypermetabolic uptake, multifocal nodal involvement, numerous parenchymal pulmonary nodules, multiple liver lesions, a large splenic lesion, and bone lesions. Bone marrow and cerebrospinal fluid analyses were negative. Peripheral EBV VL was 12 000 IU/mL and serology was positive for EBV IgM/viral-capsid antigen IgG. A supraclavicular lymph node biopsy revealed sheets of large B-cell infiltrates showing morphologic atypia positive for CD20, PAX5, MUM1, BCL6 (variable), BCL2, and EBV Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNAs with focal CD30 positivity. Findings were consistent with an ICC diagnosis of monomorphic PTLD, with DLBCL histology, EBV+ (WHO 2022 nomenclature DLBCL, EBV+, post-SOT). She was treated with 6 cycles of rituximab plus low-dose cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2/cycle) and prednisone (cyclophosphamide and prednisone + rituximab [CPR] regimen) as per Children's Oncology Group (COG) protocol ANHL0221 and achieved complete remission (CR).19

Monomorphic PTLD with EBV+ DLBCL histology (EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL)

EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL presents a unique clinical conundrum.20 Patients often present with advanced-stage disease with seemingly innumerable nodal and extranodal lesions, similar to de novo, aggressive DLBCL in immunocompetent patients. Nonetheless, widespread, advanced EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL (as in case 2) can be cured with less-intensive, low-dose chemotherapy regimens with or without rituximab, or rituximab monotherapy.7,19,21-24 These patients are included in the aforementioned spectrum of quintessential PTLD, characterized as lymphoid neoplasia rather than malignancy.

Favorable outcomes for patients like the one above are unfortunately contrasted by poor outcomes in a subset of patients with refractory or relapsed EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL, classified as lymphoid malignancy (posttransplant lymphoma). Event-free survival (EFS) for children/adolescents with monomorphic PTLD has generally plateaued at 70% despite anti-CD20 moAbs and EBV-directed cellular therapies (Table 4).19,21-23,25 There is thus a favorable (and fortunately majority) subset of patients with EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL that can be cured with less-intensive treatment and a subset with unfavorable outcomes for whom more-intensive, B-cell lymphoma (BCL) regimens are indicated. Unfortunately, the 2 are indistinguishable by morphology. However, a recent translational study demonstrated that pediatric PTLD-DLBCL is biologically different from and genetically less complex than adult PTLD-DLBCL and de novo pediatric DLBCL. Additionally, the presence of somatic alterations in cases of pediatric PTLD-DLBCL were associated with worse outcomes.7 Ultimately, these data suggest that molecular classification may play a future role in risk stratification for pediatric EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL. Discovery of tools that can reliably predict which patients can be classified as quintessential PTLD and cured with less-intensive EBV-directed therapies vs posttransplant lymphomas requiring conventional BCL regimens is needed.

Treatment outcomes for pediatric PTLD in solid organ transplant recipients

| Study . | N . | EBV+ . | ND PTLD . | Polymorphic . | Monomorphic PTLD . | Treatment regimen . | Overall outcome . | Polymorphic outcome . | M-DLBCL outcome . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLBCL . | HGBCL . | BL . | Other . | |||||||||

| US multicenter (P) | 36 | 36 (100%) | 0 | Not specified | Cy-pred | 2-yr RFS 69% | Not specified | Not specified | ||||

| Germany multicenter (R) | 55 | 32/46 (70%) | 1 (2%) | 8 (15%) | 26 (47%) | 14 (25%) | 6 (11%) | Variousa | 5-yr EFS 59% | 5-yr EFS 66% | 5-yr EFS 68% | |

| COG ANHL0221 (P) | 55 | 55 (100%) | 0 | 8/40 (20%) | 32/40 (80%) CD20+ monomorphic | 0 | Ritux + Cy-pred (CPR) | 2-yr EFS 71% | 2-yr EFS 58% | 2-yr EFS 76% | ||

| Germany Ped PTLD pilot 2005 (P) | 49 | 44 (90%) | 0 | 12 (24%) | 24 (49%) | 6 (12%) | 7 (14%) | 0 | Ritux induction, then Ritux vs mCOMP based on response | 5-yr EFS 67% | Not specified | Not specified |

| Canada multicenter (R) | 55 | 35 (64%) | 0 | 0 | 23 (42%) | 0 | 25 (45%) | 7 (13%) | Variousb | 3-yr EFS 62% | Not applicable | Not specified |

| Germany multicenter kidney transplant (R) | 20 | Not specified | 0 | 4 (20%) | 13 (65%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | Ritux monotherapy (n = 18), Ritux/mCOMP (n = 2) | 18/20 continuous CR (90%) | 4/4 continuous CR (100%) | 11/13 continuous CR (85%)c |

| COG ANHL1522 (P) | 18 | 18 (100%) | 0 | 3 (17%) | 15 (83%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ritux + EBV T cells | 2-yr EFS 61% | Not specified | Not specified |

| United Kingdom and Spain multicenter (R) | 56 | 47/52 (90%) | 0 | 0 | 42 (75%) | 6 (11%) | 8 (14%) | 0 | Variousd | 5-yr EFS 64% | Not applicable | 26/42 continuous 1st CR (62%) |

| Study . | N . | EBV+ . | ND PTLD . | Polymorphic . | Monomorphic PTLD . | Treatment regimen . | Overall outcome . | Polymorphic outcome . | M-DLBCL outcome . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLBCL . | HGBCL . | BL . | Other . | |||||||||

| US multicenter (P) | 36 | 36 (100%) | 0 | Not specified | Cy-pred | 2-yr RFS 69% | Not specified | Not specified | ||||

| Germany multicenter (R) | 55 | 32/46 (70%) | 1 (2%) | 8 (15%) | 26 (47%) | 14 (25%) | 6 (11%) | Variousa | 5-yr EFS 59% | 5-yr EFS 66% | 5-yr EFS 68% | |

| COG ANHL0221 (P) | 55 | 55 (100%) | 0 | 8/40 (20%) | 32/40 (80%) CD20+ monomorphic | 0 | Ritux + Cy-pred (CPR) | 2-yr EFS 71% | 2-yr EFS 58% | 2-yr EFS 76% | ||

| Germany Ped PTLD pilot 2005 (P) | 49 | 44 (90%) | 0 | 12 (24%) | 24 (49%) | 6 (12%) | 7 (14%) | 0 | Ritux induction, then Ritux vs mCOMP based on response | 5-yr EFS 67% | Not specified | Not specified |

| Canada multicenter (R) | 55 | 35 (64%) | 0 | 0 | 23 (42%) | 0 | 25 (45%) | 7 (13%) | Variousb | 3-yr EFS 62% | Not applicable | Not specified |

| Germany multicenter kidney transplant (R) | 20 | Not specified | 0 | 4 (20%) | 13 (65%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | Ritux monotherapy (n = 18), Ritux/mCOMP (n = 2) | 18/20 continuous CR (90%) | 4/4 continuous CR (100%) | 11/13 continuous CR (85%)c |

| COG ANHL1522 (P) | 18 | 18 (100%) | 0 | 3 (17%) | 15 (83%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ritux + EBV T cells | 2-yr EFS 61% | Not specified | Not specified |

| United Kingdom and Spain multicenter (R) | 56 | 47/52 (90%) | 0 | 0 | 42 (75%) | 6 (11%) | 8 (14%) | 0 | Variousd | 5-yr EFS 64% | Not applicable | 26/42 continuous 1st CR (62%) |

Various regimens included RIS only (n = 6, 1 nondestructive, 2 polymorphic, 3 monomorphic DLBCL), rituximab (n = 6), or various combinations of dose-reduced mature B-cell lymphoma chemotherapy regimens.

Various regimens included CPR (n = 14, 8 DLBCL & 6 BL) and rituximab + LMB96 (n = 22, 17 BL & 5 DLBCL), rituximab monotherapy (n = 4), and other.

Of the 2 patients with M-DLBCL-PTLD who relapsed, one received ritux/mCOMP, the other ritux monotherapy. The single patient with BL received ritux/mCOMP.

Various regimens include RIS only (n = 6, 5 DLBCL & 1 HGBCL), rituximab (n = 26, 21 DLBCL, 4 HGBCL, 1 BL), CPR/R-COP/COP (n = 24, 16 DLBCL, 1 HGBCL, 7 BL).

COG, Children's Oncology Group; CPR, low-dose cyclophosphamide, prednisone, and rituximab; CR, complete remission; cy-pred, low-dose cyclophosphamide and prednisone; EFS, event-free survival; HGBCL, high-grade B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; mCOMP, moderate cyclophosphamide, vincristine, methotrexate, and prednisone regimen; M-DLBCL, monomorphic DLBCL; ND, nondestructive; (P), prospective; (R), retrospective; R-COP/COP, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone +/− rituximab; RFS, relapse-free survival; RIS, reduction of immune suppression; ritux, rituximab; yr, year.

Association of EBV with PTLD histology

| Typically EBV+ (>95%) . | Usually EBV+ (>75%) . | Infrequently EBV+ (<50%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Nondestructive PTLD | Monomorphic DLBCL | Monomorphic high-grade B-cell lymphoma |

| Polymorphic PTLD | Monomorphic Burkitt lymphoma | Monomorphic T/NK-cell lymphoma |

| Classic Hodgkin lymphoma PTLD | Monomorphic plasma cell neoplasm |

| Typically EBV+ (>95%) . | Usually EBV+ (>75%) . | Infrequently EBV+ (<50%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Nondestructive PTLD | Monomorphic DLBCL | Monomorphic high-grade B-cell lymphoma |

| Polymorphic PTLD | Monomorphic Burkitt lymphoma | Monomorphic T/NK-cell lymphoma |

| Classic Hodgkin lymphoma PTLD | Monomorphic plasma cell neoplasm |

Polymorphic PTLD

Polymorphic PTLD is characterized by destructive lymphocytic infiltrates that efface the surrounding lymphoid tissue architecture and is virtually always EBV+ (Table 5). These polymorphous lesions are composed of B cells spanning all stages of development, but the lymphoproliferative populations are usually monoclonal.13 This EBV-driven lymphoproliferation can typically be halted from true malignant transformation by immune control of EBV (RIS) or EBV-directed therapy (rituximab). Though less common, some cases require treatment with low-dose chemotherapy, and/or are refractory, ultimately behaving like posttransplant BCL.17

Polymorphic PTLD is challenging to characterize because few clinical trials capture these patients. When included, they may represent the most aggressive cases and reflect selection bias. Prospective clinical trials for pediatric PTLD have excluded nondestructive PTLD and polymorphic PTLD that resolves after RIS. Data reported by the COG and German Pediatric-PTLD registry demonstrate that outcomes for polymorphic PTLD were not significantly different from those for monomorphic disease (Table 4).19,22 Retrospective studies have included polymorphic PTLD, including patients treated with RIS only, with mixed results.17,26 Polymorphic PTLD may best reflect the shortcomings of morphological classification systems in establishing prognostic implications. Additionally, polymorphic lesions can be seen concurrently with monomorphic PTLD and, at times, can be difficult to differentiate by histology.19 Based on available data, we can conclude that the majority of patients with polymorphic PTLD are curable with RIS or rituximab monotherapy, but that a subset will require chemotherapy and some will relapse despite it. Therefore, in our graphical depiction of quintessential PTLD, polymorphic spans the breadth of lymphoproliferation, mostly falling into the category of lymphoid neoplasia, but extends from B-cell hyperplasia to malignant transformation (Figure 1).

Treatment of monomorphic EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL and polymorphic PTLD

Precise histological categorization of PTLD subtype is paramount in determining optimal frontline therapy. Stratification between nondestructive PTLD vs polymorphic and monomorphic EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL establishes the framework for treatment.

There remains some debate regarding the optimal first-line treatment for polymorphic or monomorphic EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL. One treatment option supported by data from a prospective clinical trial includes 6 cycles of low-dose CPR from the COG study ANHL0221, which included EFS for 4 patients with fulminant PTLD as well.19

Rituximab monotherapy, while the alternative of choice, lacks evidence from prospective trials. Preliminary data from a multicenter prospective pilot study in Germany used a sequential approach of 3 doses of rituximab weekly, followed by disease evaluation.23 Those with partial response or CR received an additional 3 rituximab doses, while others received escalated therapy with rituximab plus chemotherapy (low-dose cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and 300 mg/m2/dose methotrexate). Twenty-six of 49 patients (53%) remained in continuous CR after rituximab monotherapy with a median follow-up of 4.9 years, while 6 relapsed. Ten of 15 patients who required escalation to chemotherapy achieved CR. The estimated 5-year EFS was 67% for the entire cohort.23

These data are supported by retrospective studies demonstrating curative potential of rituximab for EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL; however, small cohort size and selection bias are major limitations.24,27 Ultimately, because comprehensive data are lacking, it is challenging to make definitive recommendations regarding efficacy of rituximab monotherapy for monomorphic EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL. Nevertheless, evidence suggests a subset of patients with monomorphic EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL are curable with rituximab monotherapy.

Regardless of frontline therapy, published prospective and retrospective data report curative outcomes between 60% and 70% (Table 4), which are modest compared with immunocompetent pediatric patients with de novo BCL. This reality underscores the need for prospective diagnostic tools that may enable precise risk stratification to inform tailored therapy.

Post-transplant lymphomas

In the conceptual framework described above, all other monomorphic PTLD is considered posttransplant lymphoma, thus treatment is based on established guidelines in immunocompetent patients with the same histology. Monomorphic PTLD can represent any of the dozens of WHO-defined lymphoma histologies.

Post-transplant mature BCL

Based on existing evidence that patients with monomorphic BL-PTLD have significantly inferior survival compared with monomorphic PTLD-DLBCL, it is widely accepted to treat such patients similar to those with de novo BL.22 A retrospective multicenter study described 35 children with monomorphic BL. Of 15 patients who received less-intensive PTLD therapy (CPR or rituximab), only 6 were event-free survivors.28 In a multicenter study from the United Kingdom and Spain of monomorphic PTLD, 4 of 8 with BL-PTLD achieved continuous remission with rituximab plus low-dose chemotherapy. These outcomes are not surprising, given the clear biological overlap with de novo BL.7 We can thus conclude that these biologically related entities with similar mutational profiles should be treated the same, particularly given the high cure rates with contemporary pediatric BL therapy.29

Data are severely lacking for other mature BCL histologies, making it challenging to declare an optimal treatment approach (Table 4). High-grade BCL have been reported in the posttransplant setting, but whether these patients require treatment similar to de novo mature BCL vs with low-dose chemotherapy is yet unestablished.23 Clinical decision-making may hinge on the PTLD's EBV status. In a multicenter retrospective study of 36 children with EBV− monomorphic PTLD (31 DLBCL, 5 BCL not otherwise specified), 8 of 15 (53%) patients treated with lower-intensity chemotherapy or rituximab monotherapy either relapsed or experienced disease progression.30 Definitive conclusions cannot be drawn given the small, heterogeneous retrospective cohorts, thus extrapolation from adult studies is warranted. In adults, EBV− monomorphic PTLD-DLBCL in the posttransplant setting is distinct from EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL. Shared features with de novo DLBCL that occurs in immunocompetent adults suggests they should be approached similarly.11

Other post-transplant lymphomas

Other post-transplant lymphomas are even less common. HL-PTLD in children typically shares clinical overlap with immunocompetent HL, except for a much higher percentage of cases being EBV associated. Patients are often treated with conventional HL chemotherapy, and outcomes, where reported, are similar to those of immunocompetent children and adults.31,32 Monomorphic PTLD with T-cell lymphoma and plasma cell neoplasm histologies are extremely rare but have been reported, even in the pediatric population.33-36 In-depth discussion of these entities goes beyond the scope of this review, but clinicians should be aware of these entities and treat as they would in immunocompetent settings.

Future directions

The relationship between EBV and PTLD is complex. Posttransplant EBV infection usually does not lead to PTLD, and asymptomatic EBV viremia can be managed with RIS and close monitoring. Risk thresholds of extreme EBV viremia have yet to be comprehensively defined. Preemptive rituximab has been used for persistent high EBV VL, or when RIS is not feasible; however, the reduction in viremia is typically transient, and there is no evidence that this prevents PTLD.37 These topics are discussed in the International Pediatric Transplant Association guidelines.38,39

Although EBV drives lymphoproliferation in the B-cell compartment through lytic activation in quintessential PTLD, its association with posttransplant lymphoma may be tangential. In both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients with BL, for example, EBV is only one aspect of a complex network of molecular pathways contributing to lymphomagenesis.40 Despite incredible progress in EBV-specific cytotoxic T cells, neither these nor the addition of rituximab to conventional chemotherapy have resulted in overall improvements in outcomes for children with PTLD.19,25 This suggests that the 30% to 40% of patients who are not cured with less-intensive frontline regimens may suffer from molecular mechanisms of lymphomagenesis unrelated to EBV. Future studies aimed at further decoding the molecular heterogeneity of pediatric PTLD may inform risk stratification and identification of subsets of patients most likely to respond to EBV-directed therapy vs alternative approaches.7

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Nader Kim El-Mallawany: no competing financial interests to declare.

Rayne H. Rouce: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Nader Kim El-Mallawany: off-label use of disease-specific cytotoxic chemotherapy in pediatric patients is discussed.

Rayne H. Rouce: off-label use of disease-specific cytotoxic chemotherapy in pediatric patients is discussed.