Abstract

Acute pain in sickle cell disease (SCD) involves multiple, complex downstream effects of vaso-occlusion, ischemia, and inflammation, ultimately resulting in severe and sudden pain. Historically, opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been the cornerstone of treatment for acute SCD pain. However, given the evolving understanding of the complexity of pain pathways in SCD and the desire to avoid NSAID and opioid-induced side effects, a multimodal approach is needed to effectively treat acute SCD pain. In this article we review recent research supporting the utilization of nonopioid pharmacologic interventions and nonpharmacologic interventions while also describing the research questions that remain surrounding their use and efficacy and effectiveness in the management of acute SCD pain. Furthermore, we review care delivery processes shown to improve acute SCD pain outcomes and highlight areas where more work is needed. Through this comprehensive approach, alternative mechanistic pathways may be addressed, leading to improved SCD pain outcomes.

Learning Objectives

Describe nonopioid pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions for the management of acute SCD pain

Describe the care delivery approaches that have been demonstrated to improve acute SCD pain outcomes

Appreciate that the management of acute pain in SCD necessitates a multimodal and multidisciplinary approach

CLINICAL CASE

A 16-year-old girl with hemoglobin SC sickle cell disease (SCD) complicated by chronic pain presents to the emergency department (ED) for the third time in the last 6 weeks due to acute left leg pain. She takes 2 000 mg (30 mg/kg/d) of hydroxyurea daily. During previous ED presentations, she was rapidly triaged, and intravenous (IV) morphine was administered up to 3 doses, with pain evaluation after each dose. Analgesic ED interventions were not successful in controlling her pain, and she was hospitalized for further pain management. During previous hospitalizations, acute pain had been managed with morphine patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). She reports that all previous medication management has been ineffective in alleviating her acute pain. Given this is her third hospitalization for acute pain in 6 weeks, additional acute pain management strategies are discussed.

Introduction

Recurrent acute pain episodes are the hallmark of SCD and the most common cause of ED visits and hospitalizations for individuals living with SCD.1 Acute SCD pain is characterized by sudden-onset severe pain commonly located in the extremity, back, or chest. Acute pain events can begin within the first year of life and continue into adulthood, leading to significant morbidity and negative effects on patients' health-related quality of life. The pathophysiology of acute pain is complex and poorly understood, involving mechanisms including but not limited to increased red blood cell adhesion, inflammation, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and nervous system sensitization.2 The complexity of the integrated pain pathways and the lack of mechanistic understanding leads, in part, to challenges in SCD acute pain treatment. The 2014 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Expert Panel Report for the management of SCD provided guidance on acute pain based on expert consensus and limited research.3 In 2020 the American Society of Hematology developed recommendations based on current evidence.4 The mainstay treatment of acute SCD pain is IV opioids. However, prolonged opioid utilization over a life span as well as escalating doses of opioids for opioid-refractory pain can cause tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia, resulting in further opioid-refractory pain. Opioid side effects such as respiratory depression, constipation, and nausea can exacerbate SCD-related complications. Alternative and adjunctive methods to effectively treat acute SCD pain have been explored to reduce opioid exposure and provide potentially more effective analgesia. Optimal SCD acute pain management requires an individualized approach encompassing pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions delivered via multidisciplinary care teams tailored to SCD management. Given the multifaceted nature of acute SCD pain, a comprehensive approach involving multiple analgesic targets is often required. This article reviews evidence-based approaches for SCD acute pain management beyond opioids and NSAIDs, with an emphasis on a multimodal approach.

Nonopioid pharmacologic pain interventions

Ketamine

Ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, interrupts pain signal transmission to the central nervous system. Because of its distinct mechanism of action, ketamine does not carry the same side effect profile as opioids and has demonstrated antihyperalgesia effects, the reduction of opioid tolerance, and the prevention of opioid hyperalgesia in mouse models.5,6 Traditionally, ketamine has been used as a general anesthetic; however, in the last decade, data show that subanesthetic continuous infusions of ketamine (<1 mg/kg/h) are an effective adjunctive analgesic for refractory acute SCD pain.7-9 Recent systematic reviews of ketamine use in acute SCD pain that include observational studies found improvement in pain and opioid consumption with low-dose ketamine infusions and conclude the drug is a safe and effective treatment for acute SCD pain.8,10 Given the evidence, subanesthetic ketamine infusion is suggested as an adjunctive treatment for acute opioid-refractory pain in adults and children.4 Studies report transient side effects of nystagmus, visual hallucinations, dizziness, and dysphoria associated with subanesthetic ketamine for acute SCD pain management.8,10,11 Thus, experienced providers are required to monitor and to administer ketamine safely. Its use is not recommended for those with a history of seizure, stroke, psychosis, or altered mental status.

Several questions remain regarding the use of ketamine in acute SCD pain. The use of bolus dosing, rather than continuous infusion, of ketamine in the ED for the treatment of acute pain prior to admission has been explored. To date, 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have compared morphine to bolus-dose ketamine for the treatment of acute SCD pain (Table 1).11,12 In both studies ketamine was noninferior to morphine. In one trial, ketamine resulted in decreased opioid use. However, a comparison analysis in this trial did not control for the initial morphine intervention dose (not received by the ketamine group), confounding the conclusion that the ketamine group had decreased opioid use.12 Published studies report vast practice variability regarding timing of initiation, bolus vs continuous infusion, infusion duration, and timing of discontinuation.8 Guidance surrounding optimal ketamine administration practices is needed. Systematic reviews underscore the heterogeneity in responses to ketamine in acute SCD pain treatment, highlighting the need to further identify response predictors. The long-term effects of repeated ketamine exposure in the SCD population are unclear. Preliminary studies in patients with complex regional pain syndrome showed an association with low-dose repeated ketamine use and decreased cognitive function.13 SCD-specific studies are needed to determine the long-term effects of repeated use for acute pain.

RCTs comparing ketamine to morphine in treatment of acute SCD pain

| Authors . | Population . | Intervention . | Primary outcome . | Results . | Conclusions . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lubega et al., 201811 | 240 children between 7 and 18 years with severe sickle cell pain crisis | IV ketamine 1 mg/kg compared to IV morphine 0.1 mg/kg infusion over 10 min | Maximal change in NRS pain score | - IV ketamine was comparable to IV morphine in maximum change in NRS scores. - IV ketamine was associated with high prevalence (11-fold increase) of transient, mild side effects such as nystagmus, dysphoria, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, increased salivation, and pruritis compared to morphine. | - IV ketamine can be a reliable alternative to morphine in management of severe acute sickle cell pain - Further studies are needed to determine optimal ketamine dosing and infusion rate to reduce transient side effects. |

| Alshahrani et al., 202212 | 278 adults with acute sickle cell pain crisis | IV ketamine 0.3 mg/kg compared to morphine 0.1 mg/kg infused over 30 min in the ED | Mean difference in pain NRS over 2 h | - Mean pain NRS scores between ketamine and morphine groups were similar. - Those who received ketamine had reduced cumulative morphine dose (0.07 mg/kg) compared to those receiving morphine (0.13 mg/kg); P < .001. - Cumulative morphine dose analysis between groups did not control for the initial morphine intervention dose (vs initial ketamine intervention dose). This confounds study results as the morphine group would have increased morphine consumption compared to the ketamine group at time of intervention by study design. | - Early ketamine use in acute sickle cell pain had an analgesic effect with less accumulative morphine doses needed. |

| Authors . | Population . | Intervention . | Primary outcome . | Results . | Conclusions . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lubega et al., 201811 | 240 children between 7 and 18 years with severe sickle cell pain crisis | IV ketamine 1 mg/kg compared to IV morphine 0.1 mg/kg infusion over 10 min | Maximal change in NRS pain score | - IV ketamine was comparable to IV morphine in maximum change in NRS scores. - IV ketamine was associated with high prevalence (11-fold increase) of transient, mild side effects such as nystagmus, dysphoria, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, increased salivation, and pruritis compared to morphine. | - IV ketamine can be a reliable alternative to morphine in management of severe acute sickle cell pain - Further studies are needed to determine optimal ketamine dosing and infusion rate to reduce transient side effects. |

| Alshahrani et al., 202212 | 278 adults with acute sickle cell pain crisis | IV ketamine 0.3 mg/kg compared to morphine 0.1 mg/kg infused over 30 min in the ED | Mean difference in pain NRS over 2 h | - Mean pain NRS scores between ketamine and morphine groups were similar. - Those who received ketamine had reduced cumulative morphine dose (0.07 mg/kg) compared to those receiving morphine (0.13 mg/kg); P < .001. - Cumulative morphine dose analysis between groups did not control for the initial morphine intervention dose (vs initial ketamine intervention dose). This confounds study results as the morphine group would have increased morphine consumption compared to the ketamine group at time of intervention by study design. | - Early ketamine use in acute sickle cell pain had an analgesic effect with less accumulative morphine doses needed. |

NRS, numerical rating scale.

Lidocaine

Systemic lidocaine administered as a continuous IV infusion acts as an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist, reducing central nervous system sensitization and producing an antihyperalgesia effect. When given as a local anesthetic, lidocaine causes direct blockage of nociceptive fibers via infiltrative, perineural, or neuraxial blockade, and the antihyperalgesia effect is not observed. Because of its efficacy in cancer-related, opioid-refractory pain and neuropathic pain, systemic lidocaine infusions have been explored as an acute SCD pain treatment. Currently, no published RCTs or prospective studies assess the efficacy of lidocaine compared to traditional opioid therapy in individuals with SCD. In a single institution retrospective review, 11 adults with SCD presenting in acute pain received 15 trials of systemic IV lidocaine as an adjunctive pain treatment. Of the 15 trials, 8 had significant (≥20%) reduction in pain scores 24 hours after infusion. Morphine consumption was reduced on average by 32% in the same time frame.14 In another single institution cohort study, 21 adults with SCD hospitalized for acute pain received lidocaine infusions and experienced significantly decreased opioid consumption throughout hospitalization compared to those not receiving lidocaine infusions independent of treatment length or opioid use prior to the initiation of lidocaine.15 In the pediatric population, only 2 single-institution studies totaling 13 patients report on the use of adjunctive lidocaine infusions for acute SCD pain. Both studies demonstrate decreased opioid consumption and pain scores throughout hospitalization compared to before the initiation of lidocaine infusion or to other hospitalizations without lidocaine infusions.16,17

Given the lack of robust clinical trials, there are currently no established recommendations or guidance for its use in acute SCD pain treatment. An ongoing clinical trial is evaluating bolus IV lidocaine as an adjunct to opioids in the ED for acute SCD pain treatment (NCT04614610).

Regional anesthesia

Regional anesthesia is delivered via single injection or continuous infusion of an analgesic (ie, lidocaine, ropivacaine, bupivacaine), resulting in peripheral nerve blockade via the inhibition of sodium ion influx into nerve fibers. Because of its safe and efficacious use in perioperative and acute pain management in the general population, regional anesthesia has been explored as a therapeutic option for opioid refractory acute SCD pain.18 Few published case series address the use and efficacy of regional anesthesia in SCD. In 2 retrospective case series (n = 20), children with SCD who received adjunctive epidural lidocaine infusions for acute pain had reduced pain scores 24 hours after placement of the epidural catheter.19,20 One study reported decreased morphine use after placement.19 In a more recent case series, regional anesthesia via ropivacaine nerve blockade for upper extremity acute pain in 3 children with SCD was described.21 In 1 case a supraclavicular and in 2 cases an intrascalene continuous nerve block was delivered. In all cases there were decreased pain scores and opioid use. Importantly, the resolution of pain was sustained several days after hospital discharge. In adults with SCD, a case series of 9 individuals hospitalized for acute pain received a single injection of ropivacaine to a focused area of pain.22 Pain scores and opioid use were decreased after the single injection; 5 of the 9 patients received 1 repeat injection over their hospitalization (length of stay ranged 2-9 days).

Across studies, there are variable indications to initiate regional anesthesia, and further guidance is needed to determine optimal timing. Previous successful pediatric studies initiating nerve blocks in the ED for severe injuries have demonstrated feasibility and safety in up-front regional anesthesia for severe pain.23 There are no published RCTs comparing regional anesthesia with opioid therapy for acute SCD pain. Acute SCD pain is often generalized, making the use of regional anesthesia approaches limited and perhaps thereby contributing to the lack of RCTs for this pain treatment intervention. However, existing data support a conditional recommendation as an adjunctive treatment for acute SCD pain with a defined location.4 Further research is needed to determine the optimal timing of initiation of regional anesthesia and its feasibility given the need for expertise in catheter placement.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

On the third day of hospitalization, the patient reports uncontrolled pain with increasing doses and utilization of morphine PCA and NSAIDs. She is visibly uncomfortable, reporting that “nothing touches the pain.” The inpatient pain team is consulted and initiates a ketamine infusion at 0.2 mg/kg/h, later titrated to 0.1 mg/kg/h due to dizziness. The patient's pain remains unchanged. She appears anxious and expresses concern that her “pain will never go away.”

Nonpharmacologic pain interventions

Nonpharmacologic interventions for acute SCD pain encompass a range of approaches to improve coping skills, reduce stress, and optimize function. Nonpharmacologic interventions can augment pharmacologic management and include acupuncture, distraction techniques such as music or guided imagery, massage, yoga, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Data demonstrate that nonpharmacologic pain management interventions lead to decreased pain scores, morphine use, and stress levels when used in combination with pharmacologic interventions.24 While studies have explored nonpharmacologic interventions for acute SCD pain, few have been published in the last 5 years (Table 2).

Recent studies of nonpharmacologic interventions for acute SCD pain

| Authors . | Study type . | Population . | Pain intervention . | Primary outcome . | Results . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dev et al25 | Single-arm prospective study | 39 adults hospitalized for pain | 4 guided videos on mindfulness meditation, breathing exercises, and yoga | Acceptability and feasibility of the intervention | - 45% completed all 4 videos, 79% watched at least 1 video - Of those who watched videos, 72% of participants found videos helpful and enjoyed sessions - Acceptability demonstrated by positive feedback - Feasibility demonstrated by high engagement |

| Rodgers-Melnick et al26 | Retrospective review | 72 hospitalized pediatric and young adults with SCD (unspecified admission diagnosis) | 20-30 minute massage therapy sessions delivered by certified massage therapist | Descriptive of clinical delivery of massage therapy | - Significant reported mean reductions in pain, stress, and anxiety post massage |

| Reece-Stremtan, et al27 | Quasi-experimental | 29 pediatric patients hospitalized for pain | Acupuncture | Reduction in pain scores | - Acupuncture group associated with reduction in pain scores - Opioid use was not different between standard of care and acupuncture group |

| Tsai et al28 | Retrospective review | 24 pediatric patients in the outpatient or inpatient setting with acute pain | Acupuncture | Reduction in pain scores | - 65.5% of acupuncture treatments resulted in decreased pain scores - No adverse events were noted |

| Wihak et al29 | Quasi-experimental | 8 pediatric patients with SCD hospitalized for pain | Video-based biobehavioral pain-management techniques | Feasibility in the intervention | - Intervention is acceptable to adolescents and parents - Can be administered during inpatient hospitalization |

| Authors . | Study type . | Population . | Pain intervention . | Primary outcome . | Results . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dev et al25 | Single-arm prospective study | 39 adults hospitalized for pain | 4 guided videos on mindfulness meditation, breathing exercises, and yoga | Acceptability and feasibility of the intervention | - 45% completed all 4 videos, 79% watched at least 1 video - Of those who watched videos, 72% of participants found videos helpful and enjoyed sessions - Acceptability demonstrated by positive feedback - Feasibility demonstrated by high engagement |

| Rodgers-Melnick et al26 | Retrospective review | 72 hospitalized pediatric and young adults with SCD (unspecified admission diagnosis) | 20-30 minute massage therapy sessions delivered by certified massage therapist | Descriptive of clinical delivery of massage therapy | - Significant reported mean reductions in pain, stress, and anxiety post massage |

| Reece-Stremtan, et al27 | Quasi-experimental | 29 pediatric patients hospitalized for pain | Acupuncture | Reduction in pain scores | - Acupuncture group associated with reduction in pain scores - Opioid use was not different between standard of care and acupuncture group |

| Tsai et al28 | Retrospective review | 24 pediatric patients in the outpatient or inpatient setting with acute pain | Acupuncture | Reduction in pain scores | - 65.5% of acupuncture treatments resulted in decreased pain scores - No adverse events were noted |

| Wihak et al29 | Quasi-experimental | 8 pediatric patients with SCD hospitalized for pain | Video-based biobehavioral pain-management techniques | Feasibility in the intervention | - Intervention is acceptable to adolescents and parents - Can be administered during inpatient hospitalization |

Nonpharmacologic interventions target various mechanisms to reduce acute pain. For example, although the mechanisms of acupuncture analgesia are not fully understood, acupuncture is hypothesized to stimulate the release of serotonin and norepinephrine via the stimulation of particular acupoints.30 The use of virtual reality or guided imagery utilizes distraction techniques to reduce perceived pain. Nonpharmacologic interventions provide options for addressing the multifaceted nature of acute SCD pain. They target aspects of SCD pain that traditional pharmacologic interventions may not effectively treat, such as biobehavioral factors. These interventions are low risk with minimal side effects, making them appealing options as adjuvant analgesic therapies. Many individuals with SCD manage acute pain at home, and some nonpharmacologic interventions can serve as home-management strategies when combined with oral pharmacologic treatments, potentially reducing the need to seek ED care.

Existing studies of nonpharmacologic interventions show feasibility, but robust research methods that include comparison control groups are lacking, leading to difficulty drawing conclusions regarding the efficacy of the intervention. For example, in acupuncture studies, although pain scores are decreased after treatments, the effect on length of stay and opioid use are undetermined.27,28 More research is needed to better understand the mechanisms that nonpharmacologic interventions address and their impact on clinical pain outcomes.

Care delivery interventions

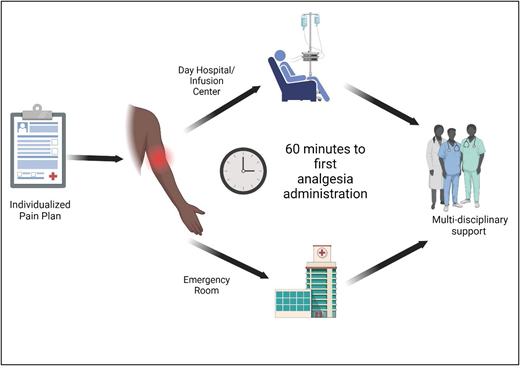

Optimal care delivery is critical to acute SCD pain management. The lack of timely analgesia delivery during acute pain can lead to exacerbated and/or prolonged pain. Patients receiving prompt analgesia for acute pain show reduced hospitalization and length of stay.31,32 Untreated pain may lead to worsening central sensitization and hyperalgesia, potentially progressing to chronic pain. Thus, optimal clinical care delivery processes (Figure 1) should be factored into acute SCD pain management because they can collectively influence pain outcomes.

Care delivery for acute pain in SCD. Optimizing care delivery practices influences clinical outcomes in acute SCD pain. Patients should have established individualized pain plans detailing the medications and dosing that have previously provided pain relief. Effective and comprehensive individualized pain plans often require multi-isciplinary collaboration with anesthesia/acute pain teams, psychology and/or psychiatry, pharmacy, physical therapy, integrative health, and child life. In the event of acute SCD pain, rapid analgesia (within 60 minutes of arrival) is critical to providing effective pain relief. The use of an individualized pain plan and day hospital/infusion center may facilitate rapid analgesia and avoid potential delays in EDs. Reassessments and repeated analgesia are recommended every 30 to 60 minutes. Ongoing multidisciplinary support for additional pain management and continuous adjustments to the individualized pain plan are needed.

Care delivery for acute pain in SCD. Optimizing care delivery practices influences clinical outcomes in acute SCD pain. Patients should have established individualized pain plans detailing the medications and dosing that have previously provided pain relief. Effective and comprehensive individualized pain plans often require multi-isciplinary collaboration with anesthesia/acute pain teams, psychology and/or psychiatry, pharmacy, physical therapy, integrative health, and child life. In the event of acute SCD pain, rapid analgesia (within 60 minutes of arrival) is critical to providing effective pain relief. The use of an individualized pain plan and day hospital/infusion center may facilitate rapid analgesia and avoid potential delays in EDs. Reassessments and repeated analgesia are recommended every 30 to 60 minutes. Ongoing multidisciplinary support for additional pain management and continuous adjustments to the individualized pain plan are needed.

Rapid triage and analgesia administration

Rapid triage, analgesia administration, and individualized care are recommended for patients presenting for acute SCD pain treatment.3,4 National guidelines recommend rapid assessment and treatment within 1 hour of ED arrival and reassessments and administration of analgesia every 30 to 60 minutes.3,4 Studies demonstrate that the early receipt of opioids and the timely administration of second opioid dose are associated with decreased hospitalization and a shorter length of stay.31,32 Notably, logistical challenges of administering rapid analgesia in the ED and adherence to this recommendation exist. In a multiyear cross-sectional study investigating time to first analgesia administration in pediatric patients presenting with uncomplicated acute SCD pain, only 48% of 4 578 visits were adherent to the recommended analgesia administration within 60 minutes.31 Barriers to rapid administration include large patient volumes and wait times, competing ED patient risk levels, inadequate staffing, difficult IV access, and a lack of provider understanding or awareness of guidelines. To mitigate identified barriers, mechanisms to facilitate rapid pain management have been proposed. Alternative routes of analgesia such as intranasal fentanyl are recommended to bypass delays from IV access, offering safe and effective treatment in the ED for acute pain.33 The use of day hospitals or infusion centers for the treatment of uncomplicated acute pain is shown to decrease the time to the initiation of the first opioid and the need for hospital admission.34

Individualized pain care plans

Individualized acute pain care plans that include personalized patient dosing (vs weight-based dosing) are recommended.4 Individualized pain plans are based on medications, personalized dosing of opioids, and all adjunctive therapies that have previously provided pain relief as per patient and provider report during previous acute pain episodes. The personalized dosing of opioids is critical as this has led to greater improvements in pain scores and lower hospital admission rates when compared to weight-based dosing.35 The implementation of such protocols is shown to decrease time to first analgesia administration,36 hospitalization rates,32 and length of stay. An RCT found that adults with SCD with patient-specific dosing of opioids in the ED for acute pain had greater pain score reduction than those given standard weight-based dosing.35 Individualized pain care plans should detail the dose, route, frequency, and potential side effects previously experienced by the individual for both ED and inpatient pain management. The pain plan should be easily accessible by the inpatient and ED providers and ideally exist and be updated regularly in the electronic medical record. Often, a multidisciplinary team is needed to create a comprehensive, individualized pain care plan. In addition to hematologists, pain-management experts such as anesthesiologists, pharmacists, psychologists, and psychiatrists can ensure multimodal input and expertise to create an individualized pain care plan.

Patient-controlled analgesia

PCA to deliver opioids for acute pain management is used at many institutions as it provides administration of opioids at intervals dictated by patients' individual needs. PCA dosing should also be included in individualized pain care plans as dosing of a PCA requires critical consideration and balance of opioid-based side effects and effective pain treatment. With PCA, providers also may add basal (continuous) IV opioid to on-demand dosing. Currently, there are no recommendations on the use of PCA basal dosing.4 Although PCA basal dosing may provide improved pain control, administering continuous opioid and increased opioid doses can lead to respiratory depression and precipitate sickle cell–related complications such as acute chest syndrome (ACS). In a study to evaluate the implementation of institutional guidelines to eliminate PCA basal infusion from children hospitalized for acute sickle cell pain, rates of ACS and hypoxia significantly decreased in children after the implementation of the practice guideline and the reduced use of PCA basal infusion.37 Conversely, ineffective pain control, particularly for chest or back sickle cell pain, may lead to poor respiratory effort and hypoventilation, increasing the risk of development of ACS. Decisions on opioid dosing and delivery should consider the risks and benefits to each patient and the clinical scenario as well as individualized pain plans to optimize effective pain control while minimizing unwanted side effects.

Multidisciplinary pain-management team

Skilled experts in pain management are needed for the safe administration and monitoring of ketamine, lidocaine, and regional anesthesia. Partners in anesthesia/acute pain are often critical in the management of acute SCD pain and can guide the escalation of medications, the selection of drugs, dosing, and the monitoring of side effects. Mental health diagnoses such as depression and anxiety are associated with increased pain intensity and frequency in SCD.38 Poor mental health may exacerbate acute pain, leading to a cycle that can be difficult to break without collaboration with psychology and/or psychiatric expertise. Integrative health teams can often offer the nonpharmacologic approaches reviewed above. In settings with limited specialized pain or integrative health expertise, palliative care may provide another source of support and guidance in SCD. Although associated with end-of-life care, the palliative care approach aims to relieve suffering and improve health-related quality of life at any stage of illness and can offer a holistic pain- and symptom-management perspective.39 Currently, research on the use of palliative care in SCD is limited and focused on advance care planning.40 A retrospective study from 2008 to 2017 investigating palliative care in SCD found that palliative care teams were more likely to be consulted during hospitalizations in which the clinical condition was thought to be terminal in those aged 40 to 55 years compared to those deemed not terminal in those aged 18 to 39 years.41 Given the complexity of SCD pain and the comprehensive palliative care approach, palliative care may be beneficial in acute SCD pain management; however, more research is needed to better define its role. Ultimately, the palliative care model may be more applicable to chronic pain, which is not addressed by this article.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

On day 4 of hospitalization, ketamine was discontinued as the patient's pain remained unchanged. Given escalating anxiety, psychology was consulted, and she began daily therapy sessions and journaling. The morphine PCA was decreased and discontinued on day 7 of hospitalization. She was discharged home with tolerable pain. She was seen by the pain team in outpatient follow-up and referred to an intensive outpatient pain program involving holistic care, which included physical therapy, pain management education, and emotional support with the goal of optimizing function.

Conclusions and future directions

Acute SCD pain treatment requires a multimodal approach that builds upon traditional treatment with opioids and NSAIDs. Recent research supports adjuvant pharmacologic interventions such as subanesthetic ketamine, lidocaine, and regional anesthesia for opioid refractory pain. Adjuvant nonpharmacologic interventions offer pain control via alternative mechanisms and have minimal risk and side effects. Care delivery plays a crucial role in acute SCD pain management and should be optimized to achieve adequate pain control. Continued research is necessary to determine optimal practices for nonopioid pharmacologic interventions and to better determine the efficacy of nonpharmacologic interventions. Finally, further understanding of the mechanisms driving acute SCD pain is needed to develop and target specific therapies for acute SCD pain.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Melissa Azul: no competing financial interests to declare.

Amanda M. Brandow: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Melissa Azul: There is nothing to disclose.

Amanda M. Brandow: There is nothing to disclose.