Abstract

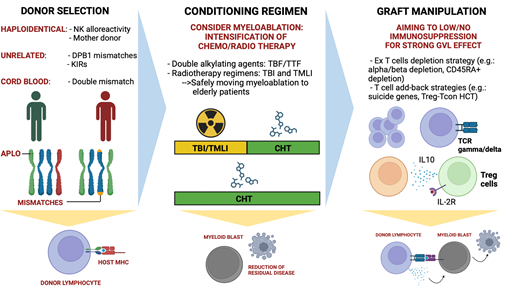

The last 20 years witnessed relevant clinical advancements in the field of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for leukemia patients. The introduction of novel conditioning regimens, a better prophylaxis and management of graft- versus-host disease, and an ameliorated posttransplant support system improved safety and, therefore, outcomes. On the other hand, leukemia relapse remains the major cause of allogeneic HCT failure. Efforts have been made to understand the mechanisms of leukemia relapse, and new insights that clarify how donor immunity exerts graft-versus- leukemia (GVL) activity are available. Such studies set the base to design novel transplant strategies that can improve disease control. In our review we begin by discussing the most relevant criteria to choose a donor that provides a strong GVL effect. We also report some of the novel conditioning regimens that aim to deliver and extend myeloablation in order to reduce the disease burden at time of graft infusion. Finally, we discuss how the graft can be manipulated to limit the use of immune suppression and ensure potent antileukemic activity.

Learning Objectives

Understand the antileukemic potential of transplant donors and consider novel conditioning regimens against residual leukemic cells

Explain major graft manipulation strategies that can enhance the graft-versus-leukemia effect

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a powerful consolidating strategy that can eradicate leukemia. Despite relevant improvements in conditioning regimens, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prevention/ treatment, and posttransplant support that increase safety and reduce transplant-related mortality, leukemia relapse is still the leading cause of HCT failure. The relapse rate is particularly high in patients with high-risk acute leukemias, such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML), with adverse genetics at diagnosis or acute leukemias with active or residual disease at transplant.

Here, we discuss recent advancements in HCT that are aimed at reducing posttransplant leukemia relapse by the selection of 3 meaningful clinical cases: (1) donor selection for relapse prevention; (2) novel conditioning regimens to increase antileukemic activity even in chemorefractory disease; (3) graft manipulation to safely boost the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect.

We are fully aware that we report a number of approaches that apply only to a minority of the routinely performed transplants. We consider them meaningful as they provide key knowledge on how to better control leukemia relapse.

CLINICAL CASE 1 – DONOR SELECTION

A 20-year-old man with AML with monosomy 7 and in good clinical condition underwent human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-haploidentical HCT in 2007. At the time of transplant, he had detectable blasts and no HLA-matched family or unrelated donor. The conditioning regimen was myeloablative and consisted of total body irradiation (TBI), thiotepa, fludarabine, and antithymoglobulin serum (ATG). T-cell depletion of the graft was chosen as a GVHD prevention strategy. Among several available family donors, we considered which donor might have features that would yield the results that were critical to ensure a potent GVL effect.

Donor selection criteria in bone marrow transplantation

A number of features are of key importance in the process of donor selection for allogeneic HCT transplantation, such as number and type of HLA mismatches, donor gender and age, and cytomegalovirus serostatus. Such features may have different impacts depending on conditioning regimen and graft composition. In our view, the donor selection criteria that are discussed play a major role in the antileukemic effect of the transplant.

Natural killer cell alloreactivity

Ruggeri and colleagues demonstrated that donor alloreactive NK cells that arise from engrafted hematopoietic stem cells after HLA-haploidentical HCT are effective at reducing the relapse rate of AML patients.1,2 (Importantly, in this case, HLA- haploidentical HCT used T-cell depletion as the sole form of GVHD prophylaxis). Donor NK cell alloreactivity can occur only in specific donor/recipient HLA combinations where recipient HLA–class I molecules are not able to bind and elicit inhibitory killer Ig-like receptors (KIRs) on donor NK cells, thus releasing NK cells from the HLA block and triggering the NK cells' killing capacity.1,3 Indeed, NK cell alloreactivity does not occur in HLA–class I fully matched HCT.

The effectiveness of donor NK cell alloreactivity against leukemic blasts has been proven in AML and pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), while not enough evidence of its clinical relevance has been proven in adult B-cell ALL (B-ALL).2,4 Indeed, the relapse incidence was very low (3%) in AML patients that underwent T cell–depleted HLA-haploidentical HCT from NK-alloreactive donors.5 Also, activating KIRs appear to play an additional role in ensuring alloreactive donor NK cell–mediated killing in pediatric ALL.4

After the discovery of donor NK cell alloreactivity in T cell– depleted HLA-haploidentical HCT, its clinical relevance has been investigated in HCT from unrelated donors that used non- T-cell–depleted grafts and consequently required posttransplant immune suppressive GVHD prophylaxis/treatment. Consequently, the role of alloreactive donor NK cells has been historically considered controversial in conventional T cell– replete HCT.6 A survival advantage has been found when ATG have been used as part of the conditioning regimen,7 but such impact has not been supported by large analyses. In these studies, the lack of T-cell depletion and the consequent need for posttransplant immune suppressive therapies, such as posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy), eliminated alloreactive natural killer (NK) cells in vivo and impaired their function and, therefore, their clinical impact.8

Thus, the presence of donor NK cell alloreactivity is considered a major criterion for donor selection in T cell–depleted HLA-haploidentical HCT in AML and pediatric ALL patients.

Mother as donor

Sex combinations between donor and recipient have been widely studied to better understand which donor provides the best outcomes. Mother as donor has been reported to allow for a survival advantage after T cell–depleted HLA-haploidentical HCT, thanks to a stronger antileukemic activity.9 The mechanisms through which such an effect occurs have not been fully elucidated, but studies showed that mothers might retain immunity against paternal HLA-haplotype antigens encountered because of transplacental trafficking between mother and child during pregnancy or delivery.10,11 Indeed, studies showed that mother donors of HLA-haploidentical HCT allow for outcomes that are comparable to those of matched unrelated donors because of a combination of lower incidence of disease relapse and a higher incidence of acute and chronic GVHD.12 Such outcomes suggest mother-derived alloreactivity against paternal antigens in the child play a relevant role that impacts HCT outcomes. More recently, a retrospective study by the Cellular Therapy and Immunobiology Working Party of the European Society for Bone Marrow Transplantation performed in a large cohort of HLA-haploidentical HCT showed that maternal donors provide a better a better survival advantage to the child in comparison to other donors. In fact, such advantage was observed in both ex vivo (with graft manipulation) and in vivo (with ATG) T cell–depleted HCT. These findings suggest that mother is to be considered the preferred donor in these conditions.13 In contrast, mother as donor is associated with an increased incidence of GVHD and, consequently, of nonrelapse mortality (NRM) in T cell–replete transplants. Thus, in this setting, donors that are alternative to the mother are preferred.14

Donor selection for a powerful GVL effect in HLA-matched or cord-blood HCT

In HLA-matched HCT, there is not enough evidence that allows a donor to be selected with the aim of enhancing the GVL effect. The results of mismatches at the HLA-DPB1 locus in unrelated HLA-matched HCT raised interest. A retrospective study in a large cohort of patients showed nonpermissive and permissive HLA-DPB1 mismatches did not differ in risk of relapse. However, the risk of relapse was lower when HLA-DPB1 mismatches in the graft-versus-host direction were considered.15 Such mismatches are not usually selected because they are followed by a higher risk of transplant-related complications and do not provide a survival advantage.16

Interesting analyses have been performed on the role of KIR haplotypes. Cooley and colleagues found that donors with group B KIR haplotypes improve relapse-free survival in unrelated HLA-matched and mismatched HCT for AML.17 The role of the group B haplotype has been further studied in larger cohorts and across diseases, but data, while promising, appear to be not yet consistent enough to recommend donor KIR genotyping for donor selection in clinical practice.18

Finally, it is important to underline that cord-blood HCT has been associated with lower relapse rates in comparison to unrelated HCT for patients with acute leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Such effect is particularly relevant in patients with minimal residual (MRD) disease at transplant.19 However, it is controversial whether the GVL effect is stronger in cord-blood HCT than in HLA-haploidentical HCT. Indeed, the level of cord unit/recipient mismatch and GVHD prophylaxis regimen impact the antileukemic activity.20,21

To date, in most centers, none of these reported donor selection criteria have become recommended clinical practice, but they might provide physicians with a possible choice to ensure higher antileukemic activity. A summary of the discussed criteria is reported in Table 1.

Donor selection criteria to enhance the GVL effect

| Criteria . | HLA-matched unrelated-donor or cord-blood HCT . | T cell–depleted haploidentical HCT . | T-cell replete haploidentical HCT . |

|---|---|---|---|

| NK cell alloreactivity | Not clear6,7 | Advantage in adult AML and pediatric ALL1,2,4 | Not clear7,8 |

| Mother as donor | N/A | Advantage13 | Father as donor preferred over mother14,73 |

| Activating KIR genes/B haplotypes | Possible advantage17,18 | Possible advantage4 | Not clear74 |

| Criteria . | HLA-matched unrelated-donor or cord-blood HCT . | T cell–depleted haploidentical HCT . | T-cell replete haploidentical HCT . |

|---|---|---|---|

| NK cell alloreactivity | Not clear6,7 | Advantage in adult AML and pediatric ALL1,2,4 | Not clear7,8 |

| Mother as donor | N/A | Advantage13 | Father as donor preferred over mother14,73 |

| Activating KIR genes/B haplotypes | Possible advantage17,18 | Possible advantage4 | Not clear74 |

Evidence for the role of some criteria for donor selection that aim to enhance the GVL effect and reduce leukemia relapse.

N/A, not applicable.

CLINICAL CASE 1 (continued)

The NK-alloreactive mother was chosen as donor because of the expected high antileukemic potential. The patient underwent rapid engraftment, had fast donor NK cell reconstitution, and experienced only few mild infectious complications in the early months after HCT. He is in complete remission since the transplant, and, today, he is considered cured.

CLINICAL CASE 2—CONDITIONING REGIMEN

A 37-year-old woman with AML with Lysine [K]-specific MethylTransferase 2A (KMT2A) rearrangement was refractory to 3 lines of therapy. Because of her young age and good performance status, she underwent HCT from a matched unrelated donor despite active disease at the time of transplant.

Conditioning regimens for allogeneic HCT in patients with AML

Myeloablative conditioning (MAC) regimens provide higher engraftment rates and stronger leukemic cytoreduction, but they are associated with higher toxicity and nonrelapse mortality. Recent randomized clinical trials support MAC as the standard of care for fit patients younger than 65 years with AML and MDS because reduced nonrelapse mortality is offset by higher relapse mortality after reduced intensity conditioning (RIC).22-25 RIC regimens or other nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens are treatment options in older patients or patients unfit for MAC regimens.22,26 MAC regimens result in lower relapse and improved survival in patients with AML with MRD before HCT, while survival is similar for MAC and RIC regimens in the absence of MRD.27-29 Further studies are necessary to assess if patients without MRD would be better candidates for RIC regimens.

Chemotherapy-only MAC regimens (MAC regimens without irradiation)

Historically, the most common MAC regimens without TBI for HCT in AML include busulfan in combination with cyclophosphamide (Bu-Cy), fludarabine (Bu-Flu), or other chemotherapy agents.22

The addition of a second alkylating agent, such as thiotepa, has been introduced as a strategy to enhance the antileukemic activity of the conditioning regimen. For AML patients in remission, the thiotepa-busulfan-fludarabine (TBF) regimen allowed for lower relapse rate than did standard Bu-Flu. This advantage was counteracted by increased GVHD and nonrelapse mortality rates that led to similar survival between the regimens.30-32 Therefore, TBF can be used as an alternative regimen to standard Bu-Cy or Bu-Flu in selected conditions.

Alternative promising strategies are reduced-toxicity conditioning regimens based on treosulfan that combine the antileukemic properties of MAC regimens with the low-toxicity profile of RIC regimens.33-37 Randomized trials reported that a treosulfan- based conditioning regimen with fludarabine was associated with superior outcomes than a Bu-Flu RIC regimen in older patients with AML and MDS.38,39 The efficacy of treosulfan-based conditioning regimens in younger patients and in patients with active disease or MRD requires further evaluation.

Irradiation-based MAC

TBI-based MAC regimens are not associated with better survival after allogeneic HCT in patients with AML when compared with those without TBI.22,40-43 A randomized trial of escalating TBI doses (15.75 Gy versus 12.0 Gy of fractionated TBI) reported no benefit because the lower relapse rate was combined with a higher NRM in the patients receiving the higher dose of TBI.44,45 Also, chemotherapy-only MAC regimens proved to exert powerful antileukemic activity (see previous section) that limited the use of TBI for patients with AML. In contrast, TBI-based conditioning regimens are still preferred for patients with ALL in many centers. Indeed, a recent noninferiority study showed that use of TBI allowed for lower relapse rate and better disease-free survival in an ALL pediatric setting.46

Total marrow/lymphoid irradiation (TMLI) is an option to deliver the leukemia ablative effect of a TBI-based MAC without increasing off-target toxicity. TMLI is administered by helical tomotherapy and delivers equal-to-TBI irradiation doses to bones, lymph nodes, and the spleen while reducing doses to visceral organs.47-51 It allows for strong leukemia ablation and immunosuppression while sparing toxicity to major organs. Promising results with low disease relapse were achieved in AML without increasing rates of GVHD or NRM compared with standard preparative regimens.50,51 Despite such encouraging results, use of TMLI is today reserved to a small minority of transplanted patients. Indeed, larger multicenter studies are needed to support the routine substitution of chemotherapy-based regimens with TMLI. Also, clear limitations of TMLI are its availability and the complexity of the approach, which requires expertise and strong collaborations between hematologists and radiation oncologists.

Adjusting intensity in RIC regimens

Despite the higher risk of leukemia relapse, RIC regimens are widely used because of their better safety profile, which allows transplant in unfit and older patients. The intensity of RIC regimens can be also modulated to aim at improving disease control. Indeed, a clear example is the use of a fludarabine-plus-melphalan RIC conditioning regimen; retrospective studies suggest that this regimen allows for a lower relapse rate than does Bu-Flu. Such an advantage did not impact survival because of a possibly higher NRM.52 In fact, a growing consensus considers the use of posttransplant antileukemic prophylactic/preemptive treatments as the best strategy to keep the relapse rate low after RIC HCT, as reported in the companion manuscript by Geramita et al (forthcoming).

CLINICAL CASE 2 (continued)

The patient received a MAC regimen that included TMLI, thiotepa, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide before HCT from a matched unrelated donor with PT-Cy as GVHD prophylaxis. Posttransplant complications were moderate chronic GVHD and thrombocytopenia. Despite having active high-risk disease at the time of transplant, she is in complete remission 4 years after HCT.

CLINICAL CASE 3 - GRAFT MANIPULATION

A 45-year-old woman with therapy-related MDS with monosomy 7 was treated with azacytidine, which kept bone marrow blasts <5%, and was evaluated for HCT. The patient had no relevant comorbidities and was considered fit for a MAC regimen. Because of the adverse genetic risk at diagnosis, her relapse incidence was expected to be high, and strategies that aimed to reduce relapse were considered.

Manipulating the graft to limit posttransplant immune suppression

Modulation of posttransplant immune suppression with the goal to reduce the dose and time of drug exposure is a clinical practice often used to somehow strengthen alloreactivity and better control the disease. Dose reduction of posttransplant immune suppressives to increase the GVL effect can be attempted in T repleted–HCT with PT-Cy (eg, lowering the mycophenolate mofetil dose after HLA-haploidentical HCT53). Also, the introduction of cytokines that can modulate donor T-cell activity (eg, IL-2 and IL-11) has been explored in several studies. In this section we will not discuss such practices, but we will focus our discussion on strategies of graft manipulation.

Historically, ex vivo T-cell depletion (initially accomplished by T-cell removal because of their ability to bind sheep red blood cells [“e-rosetting”] and later with positive selection of CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells through magnetic separation from the apheresis product) allowed for GVHD prevention after HLA-haploidentical HCT for acute leukemia54 in the absence of immune suppression. Its clinical application was limited by delayed posttransplant immune reconstitution because it resulted in high rate of infectious mortality. Also, the relapse rate in AML patients was high when donor NK alloreactivity was not present.2,55 Novel strategies of graft manipulation were employed aiming to improve such outcomes.

Depletion of T cell receptor (TCR)α/β T cells allowed for the infusion of an HLA-haploidentical graft where donor NK cells and TCRγ/δ T cells are retained. Prophylactic posttransplant immune suppression was avoided. Such an approach has been largely used in children and provided low incidence of GVHD and acceptable posttransplant immune reconstitution and relapse rates.56-58 Indeed, a report of HLA-haploidentical TCRα/β and B-cell depletion in children with acute leukemia by Locatelli and colleagues reported a 24% relapse rate and 71% 5-year leukemia-free survival.57

A further largely investigated strategy of graft manipulation is the selective depletion of CD45RA+ naive T cells. Indeed, with such an approach, CD45RO+ memory T cells are retained in the graft. CD45RA+ T cell–depleted grafts are followed by enhanced immune reconstitution and reduced viral disease, with limited incidence of GVHD if infused in the presence of GVHD prophylaxis.59 Further steps include optimizing the number of CD45RA- T cells that can be infused, determining the optimal GVHD prophylaxis regimen to maximize the benefit of these cells, and evaluating the potency of the approach against leukemia.60

Despite these improvements and different approaches, in the absence of randomized trials, ex vivo T-cell depletion is not routinely employed in adults, as outcomes appear not to compare favorably with standard unmanipulated approaches.

T-cell add-back strategies

When considering approaches that aimed to increase the antileukemic potential of T cell–depleted HCT, several authors focused on strategies that allowed for the infusion of donor T cells with low risk of GVHD. Therefore, novel technologies have been introduced to improve graft manipulation and cell engineering. Introduction of suicide genes on T cells has been evaluated as a strategy to infuse high number of donor T cells whose function could be controlled over time. Polyclonal donor T cells have been engineered to express suicide genes (eg, the herpes simplex thymidine kinase [TK]) that could be lysed after infusion by using ganciclovir. Indeed, the use of ganciclovir helped to treat and resolve GVHD, and relapse occurred in 19% of patients who underwent transplant for de novo AML and were in complete remission.61 This experience helped to understand that TK cell–dependent immune reconstitution relies on the generation of T cells that are derived from donor hematopoietic precursors by the thymus.62 A different approach involved the introduction of inducible human caspase-9 transgene (iC9) on T cells that were delivered after the infusion of purified CD34+ hematopoietic precursor cells. Like in the TK approach, the use of a small molecule dimerizing drug (AP1903) allowed for the in vivo eradication of iC9-expressing donor T cells. Control of GVHD was promising, but efficacy in disease control remains to be validated by larger studies.63,64

Other, simpler manipulation strategies involve the infusion of donor-derived regulatory T cells (Treg) to allow the infusion of higher doses of donor conventional T cells (Tcon) and minimize the use of immune suppressives. Pioneering studies have demonstrated donor Treg can successfully prevent Tcon-mediated GVHD in the majority of patients after HLA-haploidentical and cord-blood HCT.65,66 When no posttransplant immune suppression was used after TBI-based MAC HLA-haploidentical HCT with Treg/Tcon infusion, low relapse rates (<10%) were observed in AML patients.67 In this study, Tregs were simply obtained through 2-step magnetic selection (a CD8/CD19 negative selection followed by a CD25 positive selection) from a donor apheresis and were given at a 2:1 Treg:Tcon ratio. The outcomes prove that adding back donor-derived Tcon provides a potent GVL effect that is not hampered by Treg infusion if no posttransplant pharmacologic immune suppression is given. A limitation was the incidence of NRM (up to 40%), which was mainly attributable to the toxicity of the conditioning regimen and infections. To improve such outcomes and to extend a MAC conditioning regimen to older patients, a TMLI-based conditioning was used before the infusion of a T cell–depleted graft with Treg/Tcon add back. Indeed, in a cohort of patients with AML undergoing haploidentical HCT, patients up to age 50 years received TBI, while patients aged 51 to 65 years received TMLI. The relapse rate was low (4%) and the same in the 2 groups, without any increase in NRM in older patients.68 In the study, the relapse rate was similar across different AML genetic risk categories, suggesting donor immunity was key in reducing disease relapse.

A different Treg graft engineered product has been further explored in an HLA-matched setting69 with promising results. In the study, Treg cells were obtained from donor apheresis through cell sorting of the CD4+CD127lo subpopulation after magnetic selection of CD25+ cells and were given at a 1:1 Treg:Tcon ratio. In a subsequent study, the authors suggested this Treg engineered graft should be followed by a single GVHD prophylactic agent, tacrolimus, to keep GVHD incidence very low.70 An ongoing randomized study is evaluating efficacy of GVHD protection in comparison to conventional HCT strategies (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05316701). Whether such an approach coupled with single-agent immune suppression will provide potent antileukemic activity remains to be evaluated. Table 2 summarizes the most relevant studies with the use of Treg and Tcon add backs.

Main clinical studies with graft manipulation and Treg and Tcon add backs for prevention of GVHD

| Study . | HCT type . | Patients . | Treg isolation . | Treg number/kg . | Immune suppression . | GVHD outcome . | Relapse incidence . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunstein et al. (2011)66 | Cord blood | 23 | Magnetic separation In vitro expansion | 1 × 105 to 3 × 106 | MMF, CsA | aGVHD II-IV (43%) aGVHD III-IV (17%) cGVHD (14%) | 34.8% |

| Di Ianni et al. (2011)65 | Haploidentical | 28 | Magnetic separation | 2 × 106 to 4 × 106 | None | aGVHD (2/26) No cGVHD | 3.6% |

| Martelli et al. (2014)67 | Haploidentical | 43 | Magnetic separation | 2 × 106 | None | aGVHD (6/41) cGVHD (1/41) | 4.9% |

| Brunstein et al. (2016)75 | Cord blood | 11 | Magnetic separation In vitro expansion | 3 × 106 to 100 × 106 | Sirolimus, MMF | aGVHD II-IV (9%), cGVHD (0%) | 33% |

| Meyer et al. (2019)69 | HLA-matched | 7 | Magnetic separation and cell sorting | 1 × 106 to 3 × 106 | Tacrolimus or sirolimus | aGVHD (0%), cGVHD (0%) | 42.9% |

| Pierini et al. (2021)68 | Haploidentical | 50 | Magnetic separation | 2 × 106 | None | aGVHD (33%), cGVHD (2%) | 4% |

| Bader et al. (2024)70 | HLA-matched | 12 | Magnetic separation | 2.5 × 106 | None | aGVHD (58%), cGVHD (28%) | 8.3% |

| 12 | 2.5 × 106 | Tacrolimus | aGVHD (8%), cGVHD (0%) | 33% |

| Study . | HCT type . | Patients . | Treg isolation . | Treg number/kg . | Immune suppression . | GVHD outcome . | Relapse incidence . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunstein et al. (2011)66 | Cord blood | 23 | Magnetic separation In vitro expansion | 1 × 105 to 3 × 106 | MMF, CsA | aGVHD II-IV (43%) aGVHD III-IV (17%) cGVHD (14%) | 34.8% |

| Di Ianni et al. (2011)65 | Haploidentical | 28 | Magnetic separation | 2 × 106 to 4 × 106 | None | aGVHD (2/26) No cGVHD | 3.6% |

| Martelli et al. (2014)67 | Haploidentical | 43 | Magnetic separation | 2 × 106 | None | aGVHD (6/41) cGVHD (1/41) | 4.9% |

| Brunstein et al. (2016)75 | Cord blood | 11 | Magnetic separation In vitro expansion | 3 × 106 to 100 × 106 | Sirolimus, MMF | aGVHD II-IV (9%), cGVHD (0%) | 33% |

| Meyer et al. (2019)69 | HLA-matched | 7 | Magnetic separation and cell sorting | 1 × 106 to 3 × 106 | Tacrolimus or sirolimus | aGVHD (0%), cGVHD (0%) | 42.9% |

| Pierini et al. (2021)68 | Haploidentical | 50 | Magnetic separation | 2 × 106 | None | aGVHD (33%), cGVHD (2%) | 4% |

| Bader et al. (2024)70 | HLA-matched | 12 | Magnetic separation | 2.5 × 106 | None | aGVHD (58%), cGVHD (28%) | 8.3% |

| 12 | 2.5 × 106 | Tacrolimus | aGVHD (8%), cGVHD (0%) | 33% |

Some of the most relevant clinical studies that employed Treg and Tcon add backs to improve GVHD prevention and allow for strong antileukemic activity.

aGvHD, acute GvHD; cGvHD, chronic GvHD; CsA, cyclosporine A; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

In the last decade, chimeric antigen receptor engineered T (CAR-T) cells directed against leukemia-expressing antigens (eg, CD19) entered the clinic and are now routinely used. Combinations of CAR-T or CAR-NK cells with HCT are of particular interest, as the 2 approaches could synergize to deliver potent antileukemic activity. Several groups are now investigating such approaches, the descriptions of which goes beyond the aim of this review. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to believe that immune-suppression-free (or low-level-suppression) transplant strategies represent possible preferred platforms to be combined with donor-derived leukemia-specific cell immunotherapies to improve outcomes of acute leukemia patients at high-risk of relapse.

CLINICAL CASE 3 (continued)

The patient received an unrelated donor graft that was manipulated to infuse purified CD34+ cells together with Treg and Tcon at a 2:1 ratio. No posttransplant pharmacologic immune suppression was given. The patient rapidly engrafted and did not experience GVHD or any other relevant clinical complication. Full donor chimerism was observed starting at the first month after transplant. She is in complete remission with no evidence of the disease 4 years after the transplant. The present case demonstrated that a Treg engineered graft coupled with an irradiation-based conditioning regimen and an immune-suppression-free approach allowed for long-time control of this high-risk disease.

Conclusions

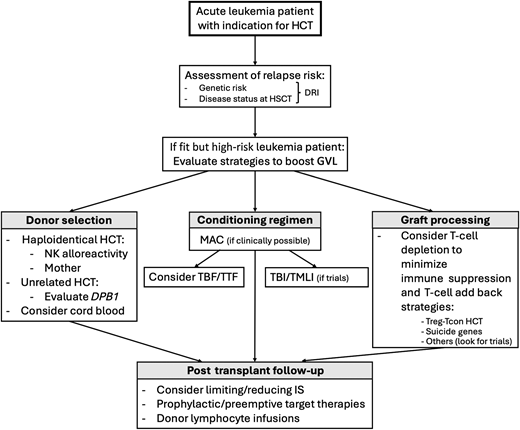

How to achieve good control of disease and provide a better cure to high-risk leukemia patients is the next missing step to be taken in HCT. In our opinion, assessment of risk of relapse through evaluation of genetics and disease status at the time of transplant, including applying useful scores such as Disease Risk Index,71 is key to design an HCT strategy that is more likely to allow positive outcomes. If a high- or very-high-risk leukemia patient is fit for HCT, several strategies can be evaluated and taken into account to increase the possibility of controlling/eradicating the disease: (1) the selection of a donor that can ensure a strong GVL effect; (2) a conditioning regimen that is possibly myeloablative, adapted to fitness and age, and able to ensure deep disease debulking; (3) a graft strategy that relies on the infusion of active donor immunity against leukemia with minimal or no posttransplant immune suppression (Figure 1). While it is clear that the cure for a subset of acute leukemia (eg, TP53- mutated/deleted AML) is still an unmet clinical need, recent studies and novel technologies allow us to adjust HCT strategy to the patient, possibly improving outcomes. It is of note that posttransplant follow-up is highly important in limiting leukemia relapse. Indeed, modulation of pharmacologic GVHD prophylaxis and the use of prophylactic or preemptive target therapies are useful tools that might impact patient survival. In conclusion, recent discoveries of mechanisms of leukemia relapse,72 knowledge of antileukemic activity of donor immunity, and the introduction of graft strategies that aim to safely strengthen GVL are getting us closer to designing transplants around patients that aim to eradicate leukemia.

Proposed clinical approach to ensure low incidence of posttransplant leukemia relapse in high-risk leukemia patients. An algorithm with a proposed approach to support clinicians with the choice of the HCT approach for fit acute leukemia patients at high risk of posttransplant relapse. DRI, Disease Risk Index; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; IS, immune suppression; TBF, thiotepa-busulfa-fludarabine; TTF, thiotepa-treosulfan-fludarabine.

Proposed clinical approach to ensure low incidence of posttransplant leukemia relapse in high-risk leukemia patients. An algorithm with a proposed approach to support clinicians with the choice of the HCT approach for fit acute leukemia patients at high risk of posttransplant relapse. DRI, Disease Risk Index; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; IS, immune suppression; TBF, thiotepa-busulfa-fludarabine; TTF, thiotepa-treosulfan-fludarabine.

Acknowledgment

AP was supported by a grant from the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC), START-UP Grant 20456. AP and LR were supported by a grant by Ministero della Salute, Programma “Ecosistema innovativo della Salute,” and Piano nazionale complementare al PNRR-E.3 - Iniziativa LSH-TA.

The authors would like to thank Massimo Fabrizio Martelli, Andrea Velardi, and Franco Aversa for their mentorship in the field of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, and Alessandra Carotti, Maria Paola Martelli, and Franca Falzetti for sharing patient care and insights. The authors also thank the nonprofit charity association “Comitato per la Vita Daniele Chianelli” for its continuous support of patients who have undergone transplants.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Antonella Mancusi: no competing financial interests to declare.

Loredana Ruggeri: no competing financial interests to declare.

Antonio Pierini: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Antonella Mancusi: There is nothing to disclose.

Loredana Ruggeri: There is nothing to disclose.

Antonio Pierini: There is nothing to disclose.