Abstract

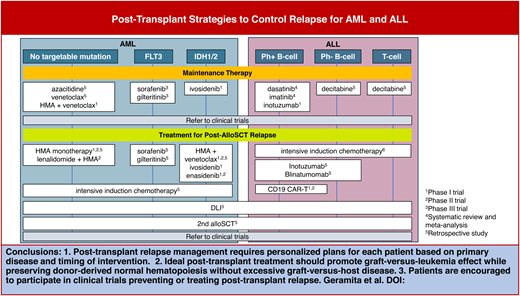

Posttransplant relapse is the most significant challenge in allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT). Posttransplant interventions, in conjunction with optimal conditioning regimens and donor selection, are increasingly supported by evidence for their potential to prolong patient survival by promoting antileukemia or graft-versus-leukemia effects. Our review begins by highlighting the current evidence supporting maintenance therapy for relapse prevention in acute myeloid leukemia and acute lymphocytic leukemia. This includes a broad spectrum of strategies, such as targeted therapies, hypomethylating agents, venetoclax, and immunotherapies. We then shift our focus to the role of disease monitoring after alloSCT, emphasizing the potential importance of early detection of measurable residual disease and a drop in donor chimerism. We also provide an overview of salvage therapies for overt relapse, including targeted therapies, chemotherapies, immunotherapies, donor lymphocyte infusion, and selected agents under investigation in ongoing clinical trials. Finally, we review the evidence for a second alloSCT (HSCT2) and discuss factors that impact donor selection for HSCT2.

Learning Objectives

Identify patients who may qualify for posttransplant maintenance therapy

Apply appropriate posttransplant monitoring strategies for relapse management

Explain current approaches and future perspectives for treating posttransplant relapse

Introduction

Posttransplant relapse after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) requires a highly personalized management plan based on the time from transplant to relapse, donor type, molecular features of the primary disease, history of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and other posttransplant complications.1 Monitoring for evidence of early relapse and dropping donor hematopoiesis (ie, chimerism) can enable early intervention, though questions remain regarding which approaches are beneficial. Treatment in the posttransplant setting must strike a balance between the efficacy and toxicities of chemotherapies and targeted agents and the promotion of the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect while avoiding excessive GVHD.

Here, we discuss recent evidence that bears on strategies to prevent and treat posttransplant relapse, using the framework provided by 3 clinical cases: 1) maintenance therapy for relapse prevention, 2) salvage therapy for relapse, and 3) second alloSCT (HSCT2) and other cellular therapies.

CLINICAL CASE 1: POSTTRANSPLANT MAINTENANCE THERAPY FOR RELAPSE PREVENTION

A 30-year-old man with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) with central nervous system involvement underwent haploidentical alloSCT with a total body irradiation-based myeloablative conditioning regimen and postgraft cyclophosphamide (PTCy). His bone marrow (BM) biopsy at posttransplant day 30 showed complete remission (CR) with negative BCR-ABL and 100% donor chimerism.

Posttransplant maintenance therapy

Maintenance therapy2 is a low-intensity treatment in the early posttransplant period, when relapse is most likely to occur, that aims to prolong remission and overall survival. Growing evidence suggests that some types of maintenance therapy may lead to improved outcomes in patients with high-risk diseases. However, the potential benefits of maintenance therapy for disease control must be balanced against the risks of hematologic toxicities and GVHD (Table 1).

Selected studies of posttransplant maintenance therapy

| Lead Author . | Year Journal . | Disease . | Therapy . | Study information . | Main clinical outcome . | Secondary clinical outcome . | Subgroup analysis . | Main clinical outcome in subgroup . | Toxicity . | Miscellaneous . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted therapy | ||||||||||

| Levis4 | 2024 JCO | FLT3-ITD AML | Gilteritinib 120 mg × 2 y | RCT glt vs placebo, n = 356 | RFS HR 0.68, P = 0.052 | MRD+ before or after HCT | RFS HR 0.5, P = 0.0065 favoring MRD+ (no benefit in MRD−) | |||

| Brissot8 | 2015 Haematologica | ALL Ph+ | TKI pretransplant and/or posttransplant | Retrospective n = 473 ALL Ph+ CR1 who underwent alloSCT n = 157 TKI after transplant | Posttransplant TKI maintenance showed benefits in leukemia-free survival (HR = 0.44; P = 0.002), overall survival (HR = 0.42; P = 0.004), and a lower relapse incidence (HR = 0.40; P = 0.01). | |||||

| Guan69 | 2024 Cancer | ALL Ph+ | Imatinib Dasatinib | Retrospective, n = 91 imatinib, n = 50 dasatinib | 5 y imat vs dasat CIR 16% vs 12% NRM 5% vs 9.8% OS 86% vs 78% | Mild GVHD higher in dasatinib | Neutropenia GI bleed in dasatinib | |||

| Fathi5 | 2023 Clin Cancer Res | IDH1 AML | Ivosidenib × 12 cycles – RP2D 500 mg daily | Phase 1, n = 18 (16 got ivo) | 2 y CIR 19% 2 y NRM 0% 2 y PFS 81% 2 y OS 88% | 6 m aGVHD 6% g2-4 | QTc prolongation in n = 2 | N = 8 stopped maintenance | ||

| Fatchi6 | 2022 Blood Adv | IDH2 AML | Enasidenib | Phase 1, n = 23 | 2 y CIR 16% 2 y PFS 69% 2 y OS 74% | 6 m aGVHD 16% g2-4, 12 m cGVHD 42% mod/sev | Neutropenia, anemia | N = 8 stopped maintenance | ||

| Cheng70 | 2024 Transplant Immunol | ALL | Ruxolitinib 5-10 mg BID | Observational, n = 8 | Relapse in 25% at 14 m f/u | aGVHD: 25% gr1-2, 0 gr3-4, 12% cGVHD | ||||

| Maintenance chemotherapy | ||||||||||

| Garcia13 | 2024 Blood Adv | MDS/AML | Aza 36 m/m2 D1-5 + ven 400 mg D1-14 × 8 42 d cycles or 12 28 d cycles | Phase 1, n = 27 96% MRD+ | mOS NR at 25 m f/u | n = 22 who got ven/aza | 2 y OS 67%, PFS 59%, NRM 0%, CIR 41% | Leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia | ||

| Fan71 | 2023 BMT | ALL | Decitabine | Retrospective, n = 65 decitabine, n = 76 control | 3 y CIR 19.6% decitabine vs 36% control, HR 0.49 | T-ALL 3 y CIR 11.7 vs. 35.9% favoring decitabine Ph- B-ALL 3 yCIR 19 vs 42% favoring decitabine | ||||

| Kent12 | 2023 BMT | AML | Ven × 1 y after HCT | Prospective, n = 49 | 1 y OS 70% | 1 y RFS 67% | Cytopenias, GI | 88% completed full year, 67% had dose interruptions | ||

| Pasvolsky10 | 2024 Clin Lympoma Myeloma Leuk | AML FLT3-neg/MDS | Aza | Retrospective matched control, n = 93 Aza, n = 257, control | 3 y CIR 29% vs 33% P = 0.09 | High risk AML/MDS | HR 0.4 CIR, P = 0.009 favoring Aza; PFS HR 0.2, P = 0.004; and AML HR 0.4, P = 0.04 | |||

| Pharmacological immunotherapy | ||||||||||

| Metheny14 | 2024 Blood Adv | ALL Ph+ | Inotuzumab – 0.6 mg/m2 identified as MTD | Phase 1, high risk of recurrence, n = 19 | 1 y nonrelapse mortality 5.6% | PFS 89% and OS 94% at 1 y with 18 m f/u | Thrombocytopenia, no VOD | |||

| Adoptive cell immunotherapy | ||||||||||

| Chapuis66 | 2019 Nat Med | AML | Wilms' Tumor Antigen 1-specific TCR transduced Epstein-Bar virus-specific donor CD8 T cells (TTCR-C4) | Phase 1 prophylactic infusion n = 12 | 3 y RFS 100%, compared to control group 54% (P = 0.002) | 1 patient developed grade 3 acute GVHD. No differences in the incidences of chronic GVHD compared to comparative control group (55% vs 61%) | ||||

| Lulla67 | 2021 Blood | AML/MDS | Donor-derived mLST | Phase 1 Adjuvant arm n = 17 (n = 12, prophylactic infusion for the patients who never relapsed after HSCT, n = 5 relapsed after HSCT but in CR after salvage therapy) | 11/17 never relapsed after mLST infusion. Median LFS not reached. | 2-year OS 77% | No grade 2 or above GVHD, or no extensive chronic GVHD | |||

| Lead Author . | Year Journal . | Disease . | Therapy . | Study information . | Main clinical outcome . | Secondary clinical outcome . | Subgroup analysis . | Main clinical outcome in subgroup . | Toxicity . | Miscellaneous . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted therapy | ||||||||||

| Levis4 | 2024 JCO | FLT3-ITD AML | Gilteritinib 120 mg × 2 y | RCT glt vs placebo, n = 356 | RFS HR 0.68, P = 0.052 | MRD+ before or after HCT | RFS HR 0.5, P = 0.0065 favoring MRD+ (no benefit in MRD−) | |||

| Brissot8 | 2015 Haematologica | ALL Ph+ | TKI pretransplant and/or posttransplant | Retrospective n = 473 ALL Ph+ CR1 who underwent alloSCT n = 157 TKI after transplant | Posttransplant TKI maintenance showed benefits in leukemia-free survival (HR = 0.44; P = 0.002), overall survival (HR = 0.42; P = 0.004), and a lower relapse incidence (HR = 0.40; P = 0.01). | |||||

| Guan69 | 2024 Cancer | ALL Ph+ | Imatinib Dasatinib | Retrospective, n = 91 imatinib, n = 50 dasatinib | 5 y imat vs dasat CIR 16% vs 12% NRM 5% vs 9.8% OS 86% vs 78% | Mild GVHD higher in dasatinib | Neutropenia GI bleed in dasatinib | |||

| Fathi5 | 2023 Clin Cancer Res | IDH1 AML | Ivosidenib × 12 cycles – RP2D 500 mg daily | Phase 1, n = 18 (16 got ivo) | 2 y CIR 19% 2 y NRM 0% 2 y PFS 81% 2 y OS 88% | 6 m aGVHD 6% g2-4 | QTc prolongation in n = 2 | N = 8 stopped maintenance | ||

| Fatchi6 | 2022 Blood Adv | IDH2 AML | Enasidenib | Phase 1, n = 23 | 2 y CIR 16% 2 y PFS 69% 2 y OS 74% | 6 m aGVHD 16% g2-4, 12 m cGVHD 42% mod/sev | Neutropenia, anemia | N = 8 stopped maintenance | ||

| Cheng70 | 2024 Transplant Immunol | ALL | Ruxolitinib 5-10 mg BID | Observational, n = 8 | Relapse in 25% at 14 m f/u | aGVHD: 25% gr1-2, 0 gr3-4, 12% cGVHD | ||||

| Maintenance chemotherapy | ||||||||||

| Garcia13 | 2024 Blood Adv | MDS/AML | Aza 36 m/m2 D1-5 + ven 400 mg D1-14 × 8 42 d cycles or 12 28 d cycles | Phase 1, n = 27 96% MRD+ | mOS NR at 25 m f/u | n = 22 who got ven/aza | 2 y OS 67%, PFS 59%, NRM 0%, CIR 41% | Leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia | ||

| Fan71 | 2023 BMT | ALL | Decitabine | Retrospective, n = 65 decitabine, n = 76 control | 3 y CIR 19.6% decitabine vs 36% control, HR 0.49 | T-ALL 3 y CIR 11.7 vs. 35.9% favoring decitabine Ph- B-ALL 3 yCIR 19 vs 42% favoring decitabine | ||||

| Kent12 | 2023 BMT | AML | Ven × 1 y after HCT | Prospective, n = 49 | 1 y OS 70% | 1 y RFS 67% | Cytopenias, GI | 88% completed full year, 67% had dose interruptions | ||

| Pasvolsky10 | 2024 Clin Lympoma Myeloma Leuk | AML FLT3-neg/MDS | Aza | Retrospective matched control, n = 93 Aza, n = 257, control | 3 y CIR 29% vs 33% P = 0.09 | High risk AML/MDS | HR 0.4 CIR, P = 0.009 favoring Aza; PFS HR 0.2, P = 0.004; and AML HR 0.4, P = 0.04 | |||

| Pharmacological immunotherapy | ||||||||||

| Metheny14 | 2024 Blood Adv | ALL Ph+ | Inotuzumab – 0.6 mg/m2 identified as MTD | Phase 1, high risk of recurrence, n = 19 | 1 y nonrelapse mortality 5.6% | PFS 89% and OS 94% at 1 y with 18 m f/u | Thrombocytopenia, no VOD | |||

| Adoptive cell immunotherapy | ||||||||||

| Chapuis66 | 2019 Nat Med | AML | Wilms' Tumor Antigen 1-specific TCR transduced Epstein-Bar virus-specific donor CD8 T cells (TTCR-C4) | Phase 1 prophylactic infusion n = 12 | 3 y RFS 100%, compared to control group 54% (P = 0.002) | 1 patient developed grade 3 acute GVHD. No differences in the incidences of chronic GVHD compared to comparative control group (55% vs 61%) | ||||

| Lulla67 | 2021 Blood | AML/MDS | Donor-derived mLST | Phase 1 Adjuvant arm n = 17 (n = 12, prophylactic infusion for the patients who never relapsed after HSCT, n = 5 relapsed after HSCT but in CR after salvage therapy) | 11/17 never relapsed after mLST infusion. Median LFS not reached. | 2-year OS 77% | No grade 2 or above GVHD, or no extensive chronic GVHD | |||

Aza, azacitinide; cGVHD, chronic GVHD; CR1, first complete remission; GI, gastrointestinal; LFS, leukemia-free survival; mLST, multiple leukemia antigen–specific T cells; mOS, median overall survival; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; NR, not reached; R2PD, recommended phase 2 dose; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Targeted therapies as posttransplant maintenance

The FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) inhibitors sorafenib and gilteritinib have each been studied as posttransplant maintenance therapies for FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukmia (AML). A 5-year follow-up of a phase 3 randomized trial showed improved overall survival (OS) at 5 years (72% vs 57%) and lower cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) (15% vs 36%) in patients who received 1 year of sorafenib maintenance compared to controls.3 The 5-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD (cGVHD) was similar in both groups. Interestingly, another randomized trial comparing 2 years of maintenance gilteritinib to placebo only showed a relapse-free survival (RFS) benefit (hazard ratio [HR] 0.515) among patients with detectable measurable residual disease (MRD) in the peritransplant period.4

In IDH1-mutant AML, a phase 1 study of ivosidenib maintenance for 1 year showed that ivosidenib was safe and well-tolerated.5 Efficacy outcomes were promising, with 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) of 81% and 2-year OS of 88%. For IDH2-mutant AML, enasidenib6 was well-tolerated as posttransplant maintenance therapy, with a 2-year PFS of 69% and 2-year OS of 74%.

In chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), a large registry study showed no benefit of posttransplant maintenance with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), perhaps because most patients were beyond first complete remission (CR1) and potentially TKI- refractory.7 Conversely, TKI maintenance posttransplant has been suggested as the standard of care for Ph+ ALL based on a European Society for Blood and Marrow Transportation (EBMT) registry analysis that reported OS (HR 0.42) and leukemia-free survival (HR 0.44) benefits with TKI maintenance.8 For Ph+ ALL with a T315I mutation, ponatinib maintenance needs further investigation.9

Hypomethylating agents and venetoclax as posttransplant maintenance

Hypomethylating agent (HMA) monotherapy has been proposed as a maintenance therapy. In a retrospective, matched control study, patients with high-risk AML and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) had lower 3-year CIR rates after azacitidine maintenance compared to controls.10 However, a subsequent randomized trial failed to demonstrate a survival benefit, though the study may have been underpowered due to better outcomes in both groups.11

Venetoclax is another potential candidate for maintenance therapy. A prospective study of AML patients12 reported a 1-year OS of over 70% and 1-year RFS of 67% in patients who received venetoclax maintenance for 1 year. As combination therapy, maintenance venetoclax with low-dose azacitidine was recently evaluated in a phase 1 trial; 96% of this cohort had detectable pretransplant MRD,13 and 2-year OS and CIR were reported as 67% and 41%, respectively. The ongoing VIALE-T trial (NCT04161885), a phase 3 randomized trial, is evaluating the azacitidine/venetoclax combination as posttransplant maintenance therapy in AML patients.

Pharmacological immunotherapies as posttransplant maintenance

Immunotherapies have also been tested in the posttransplant setting. As posttransplant maintenance, inotuzumab ozogamicin was safe with no cases of veno-occlusive disease in a phase 1 trial in Ph+ ALL.14 One-year nonrelapse mortality (NRM) and PFS were 6% and 89%, respectively. Posttransplant blinatumomab maintenance was also well-tolerated in high-risk ALL patients with a 1-year PFS of 71% and NRM of 0%.15

Posttransplant cytokine therapies have also been explored as strategies to enhance GVL. In a prospective trial in alloSCT recipients, prophylactic ultra-low dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) was well tolerated and promoted Treg and natural killer (NK) cell expansion while preserving antigen-specific T-cells.16 A phase 1/2 trial showed that prophylactic pegylated interferon-α (IFN-α) was safe in alloSCT recipients with very high-risk AML, with a CIR of 42% and NRM of 13% at 6 months.17

CLINICAL CASE 1 (continued)

The patient started posttransplant maintenance with dasatinib on day 30. He developed steroid-refractory gastrointestinal GVHD and was treated with systemic steroids and ruxolitinib, which was further complicated by invasive fungal infection requiring life-long posaconazole, leading to dasatinib dose adjustment. He discontinued dasatinib 2 years after alloSCT and remains in CR for 3 years after alloSCT.

CLINICAL CASE 2: POSTTRANSPLANT MONITORING AND SALVAGE THERAPY FOR RELAPSE

A 44-year-old woman with NPM1+, FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD)+ AML in an MRD-negative CR received a myeloablative human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched unrelated donor alloSCT. On day 30, myeloid chimerism was 100%, but T-cell chimerism was 79% and remained <80% despite tapering systemic immunosuppression. NPM1 transcripts became detectable 6 months posttransplant, and overt relapse developed after 10 months with 25% NPM1+ blasts, FLT3-ITD-negative by polymerase chain reaction, and CD3 chimerism of 78%.

Posttransplant monitoring to detect early relapse

Growing evidence suggests that posttransplant MRD monitoring can predict clinical outcomes. The premise behind such monitoring is that early low-level relapse will be more successfully treated than overt relapse. In the FIGARO trial,18 posttransplant MRD-positivity and mixed donor T-cell chimerism were independently associated with poor OS. Early complete myeloid-lineage (CD33+) donor chimerism before day 60 was reported to correlate with lower relapse rates.19 This observation supports the importance of monitoring both MRD and donor chimerism. The optimal MRD monitoring method differs based on the underlying disease and genetic abnormalities.20 We recommend checking patient-specific MRD assays from BM and blood lineage-specific chimerism on days 30, 100, 180, and 360 after alloSCT.

At the time of overt AML relapse, we recommend performing next-generation sequencing to search for targetable mutations (ie, FLT3, IDH1). For ALL, checking for CD19 or CD22 expression is critical for selecting immunotherapies. HLA loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at chromosome 6, which contains HLA genes, is observed in up to one-third of patients who relapse after haploidentical alloSCT and is another important feature to evaluate at relapse, as it impacts the utility of donor lymphocyte infusions (DLIs) and donor selection for HSCT2.21,22 Commercial assays for this are under development.

Salvage chemotherapies and targeted therapies for posttransplant relapse

There is no FDA-approved or consensus approach for treating posttransplant relapse. Thus, treatment choices are commonly made based on prior therapies, targetable mutations, and patient fitness (Table 2).

Salvage therapies for posttransplant relapse for myeloid malignancy (selected studies)

| First Author . | Year . | Regimen . | Total patients . | AML . | MDS . | DLI . | 2nd SCT . | %CR . | %ORR . | LFS or EFS . | OS/mOS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMA | |||||||||||

| Schroeder26 | 2013 | Aza+DLI | 30 | 28 | 2 | 22 (73%) | 5 (17%) | 23.0% | 30.0% | NA | mOS 117 days |

| Schroeder25 | 2015 | Aza+DLI | 154 | 124 | 28 | 105 (68%) | 19 (12.3%) | 27.0% | 33.0% | NA | 2 yr OS 29% |

| Rautenberg23 | 2020 | Aza+DLI | 151 | 90 | 49 | 105 (70%) | 17 (11%) | 41.0% | 46.0% | NA | 2 yr OS 38% |

| VEN based regimen | |||||||||||

| Aldoss31 | 2018 | HMA+VEN | 13 | 13 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 46.2% | NA | 6 months 42.3% |

| Schuler30 | 2021 | HMA/VEN | 32 | 11 (34%) | 2 (6%) | 31.0% | 47.0% | NA | mOS 3.7 months | ||

| Amit29 | 2021 | VEN+various combinations | 22 | 22 | 0 | 22 (100%) | 18.0% | 50.0% | NA | mOS 6.1 months | |

| Joshi28 | 2021 | HMA/VEN | 29 | 19 | 10 | 0 | 3.0% | 28.0% | 38.0% | mLFS in responder, 259 days; mLFS nonresponder, 35 days | mOS 79 days; mOS 403 days in responder; mOS 55 days in nonresponder |

| Zucenka33 | 2021 | Venetoclax+LDAC+ actinomycin D (Active)+DLI vs FLAG-IDA | 29 | 29 | 0 | 10 in Active vs 7 in FLAG-IDA | 3% in Active vs 12% in FLAG-IDA | 70% in Active vs 34% FLAG-IDA | 75% in Active and 66% in FLAG-IDA | mEFS 7.7 months in ACTIVE; mEFS 2 months in FLAG-IDA | mOS 13.1 months in Active; mOS 5.1 months in FLAG-IDA |

| Zuanelli Brambilla34 | 2021 | CT 41.9%, HMA 52.7%, VEN 8.1% | 148 total (AML104/ MDS 44) | 104 | 44 | 17 (11.5%) | 28 (18.9%) | NA | NA | NA | mOS 6 months for all; 2 yr 44.9% in DLI/second SCT |

| Zhao35 | 2022 | Aza+VEN+DLI | 26 | 26 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 26.9% | 61.5% | mEFS 120 days | mOS 284 days |

| Intensive chemotherapy | |||||||||||

| Krakow27 | 2022 | Intensive CT | 175 | 175 | 0 | 13 | 13 | 36% | NA | mEFS 35 days; 1 yr EFS 15% | 1 yr OS 32%; 2 yr OS 18% |

| Pharmacological immunotherapy | |||||||||||

| Craddock50 | 2019 | Aza/LEN | 29 | 24 | 5 | 2 (7%) | 3 (10%) | 40% after cycle 3 | 24% in total, 47% after cycle 3 | NA | mOS 27 months in responder, 10 months in nonresponder |

| Schroeder51 | 2023 | LEN+ Aza+DLI | 59 | 23 | 24 | 34 | Not reported | 50% | 56% | Not reported | 1 yr 65% |

| Henden53 | 2019 | CT (FLAG)+ IFN-2α+DLI | 29 | 13 | 6 | 11 | 2 yr PFS 24% | 2 yr OS 31% | |||

| Adoptive cell immunotherapy | |||||||||||

| Lulla67 | 2021 | Donor-derived mLST | 8 | 7 | 1 transformed to AML | NA | 1 | 1/8% | 2/8% (1 CR and 1 PR) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Krakow68 | 2024 | HA-1 TCR transduced T-cells | 9 | 5 | 1 | NA | NA | 4/9% | 4/9% | Not reported | Not reported |

| First Author . | Year . | Regimen . | Total patients . | AML . | MDS . | DLI . | 2nd SCT . | %CR . | %ORR . | LFS or EFS . | OS/mOS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMA | |||||||||||

| Schroeder26 | 2013 | Aza+DLI | 30 | 28 | 2 | 22 (73%) | 5 (17%) | 23.0% | 30.0% | NA | mOS 117 days |

| Schroeder25 | 2015 | Aza+DLI | 154 | 124 | 28 | 105 (68%) | 19 (12.3%) | 27.0% | 33.0% | NA | 2 yr OS 29% |

| Rautenberg23 | 2020 | Aza+DLI | 151 | 90 | 49 | 105 (70%) | 17 (11%) | 41.0% | 46.0% | NA | 2 yr OS 38% |

| VEN based regimen | |||||||||||

| Aldoss31 | 2018 | HMA+VEN | 13 | 13 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 46.2% | NA | 6 months 42.3% |

| Schuler30 | 2021 | HMA/VEN | 32 | 11 (34%) | 2 (6%) | 31.0% | 47.0% | NA | mOS 3.7 months | ||

| Amit29 | 2021 | VEN+various combinations | 22 | 22 | 0 | 22 (100%) | 18.0% | 50.0% | NA | mOS 6.1 months | |

| Joshi28 | 2021 | HMA/VEN | 29 | 19 | 10 | 0 | 3.0% | 28.0% | 38.0% | mLFS in responder, 259 days; mLFS nonresponder, 35 days | mOS 79 days; mOS 403 days in responder; mOS 55 days in nonresponder |

| Zucenka33 | 2021 | Venetoclax+LDAC+ actinomycin D (Active)+DLI vs FLAG-IDA | 29 | 29 | 0 | 10 in Active vs 7 in FLAG-IDA | 3% in Active vs 12% in FLAG-IDA | 70% in Active vs 34% FLAG-IDA | 75% in Active and 66% in FLAG-IDA | mEFS 7.7 months in ACTIVE; mEFS 2 months in FLAG-IDA | mOS 13.1 months in Active; mOS 5.1 months in FLAG-IDA |

| Zuanelli Brambilla34 | 2021 | CT 41.9%, HMA 52.7%, VEN 8.1% | 148 total (AML104/ MDS 44) | 104 | 44 | 17 (11.5%) | 28 (18.9%) | NA | NA | NA | mOS 6 months for all; 2 yr 44.9% in DLI/second SCT |

| Zhao35 | 2022 | Aza+VEN+DLI | 26 | 26 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 26.9% | 61.5% | mEFS 120 days | mOS 284 days |

| Intensive chemotherapy | |||||||||||

| Krakow27 | 2022 | Intensive CT | 175 | 175 | 0 | 13 | 13 | 36% | NA | mEFS 35 days; 1 yr EFS 15% | 1 yr OS 32%; 2 yr OS 18% |

| Pharmacological immunotherapy | |||||||||||

| Craddock50 | 2019 | Aza/LEN | 29 | 24 | 5 | 2 (7%) | 3 (10%) | 40% after cycle 3 | 24% in total, 47% after cycle 3 | NA | mOS 27 months in responder, 10 months in nonresponder |

| Schroeder51 | 2023 | LEN+ Aza+DLI | 59 | 23 | 24 | 34 | Not reported | 50% | 56% | Not reported | 1 yr 65% |

| Henden53 | 2019 | CT (FLAG)+ IFN-2α+DLI | 29 | 13 | 6 | 11 | 2 yr PFS 24% | 2 yr OS 31% | |||

| Adoptive cell immunotherapy | |||||||||||

| Lulla67 | 2021 | Donor-derived mLST | 8 | 7 | 1 transformed to AML | NA | 1 | 1/8% | 2/8% (1 CR and 1 PR) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Krakow68 | 2024 | HA-1 TCR transduced T-cells | 9 | 5 | 1 | NA | NA | 4/9% | 4/9% | Not reported | Not reported |

Aza, azacitinide; CT, chemotherapy; EFS, event-free survival; FLAG-IDA, Fludarabine, Cytarabine (Ara-C), Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), and Idarubicin; LEN, lenalidomide; LFS, leukemia-free survival; mEFS, median event-free survival; mLST, multiple leukemia antigen–specific T-cell; mOS, median overall survival; NA, not reported; VEN, venetoclax.

For myeloid malignancies, HMA monotherapy achieves a 9%-20% CR rate, with median survival of only 3-6 months.23–26 The combination of HMA with venetoclax does not offer substantial improvement over monotherapy, with a 30% CR rate and median survival of only 6 months.27–31 Although not yet documented in the posttransplant relapse setting, treatment with HMA and venetoclax may be reasonable for patients with IDH1/2 mutations, as this subgroup showed favorable outcomes in the frontline setting.32 Higher-intensity regimens containing fludarabine, cytarabine, and idarubicin, with or without venetoclax, have also been used for younger and fit patients. However, even these only yielded a CR in up to 36% of patients, and responses were not durable, with a median survival of 6 months.27,33–35 Given these disappointing outcomes, the benefits of high-intensity cytotoxic therapies must be weighed against their serious side effects, including end-organ damage, prolonged cytopenias, opportunistic infections, and early mortality rates as high as 10%.27

Targeted therapies can be applied to selected patients with actionable mutations. TKIs are effective salvage therapies for chronic myeloid leukemia that has relapsed after alloSCT (3-year adjusted OS of 54% when used as monotherapy).36 Ivosidenib and enasidenib were well tolerated without GVHD37,38 in alloSCT recipients; however, they have not been prospectively studied specifically for posttransplant relapse. FLT3 inhibitors were reported to enhance GVL through IL-15 induction39,40 and reduce expression of exhaustion markers in alloreactive CD8 T-cells40 in preclinical models. Retrospective studies reported that sorafenib is tolerable, with CR rates of 38% to 53% and 1-year OS of 22% to 66%.41,42 Revumenib, a menin inhibitor, showed clinical efficacy with 23%-30% CR rates in relapsed or refractory lysine methyltransferase 2A (KMT2A) rearranged or NPM1-mutant AML, including the patients relapsing after alloSCT.43,44

Donor lymphocyte infusions

DLIs were initially introduced and found to be successful in treating chronic phase CML relapse.45 However, for high-risk diseases (AML, ALL, MDS, and blast-phase CML), DLI monotherapy rarely controls disease and is therefore commonly combined with salvage chemotherapies. Several clinical trials have explored the role of prophylactic or preemptive DLI, especially with in vivo or ex vivo T cell depletion, but whether this reduces relapse is inconclusive due to a lack of prospective controlled studies.46 Nevertheless, large retrospective registry data consistently support the observation that long-term survival is only achieved in patients who receive DLI or HSCT2.34,47 Thus, DLI should at least be considered as a treatment option in combination with cytoreductive salvage therapies or other experimental approaches.

Pharmacologic immunotherapies for posttransplant relapse

Although immunotherapy has been proposed as a strategy to promote GVL, the GVHD risk, which is related to the robust activation of alloreactive T-cells, can be significant. A phase 1/2b trial reported acceptable safety outcomes after ipilimumab for posttransplant AML relapse, with 14% incidence of GVHD and 21% incidence of immune-related adverse events (irAEs); the overall response rate (ORR) was 31%, predominantly effective in extramedullary AML. However, subsequent multicenter trials of combined ipilimumab and decitabine showed minimal clinical effects (ORR 20%) and relatively high incidences of GVHD (36%) and irAEs (16%). In general, the use of checkpoint inhibitors in the posttransplant setting is limited to Hodgkin's disease (CR 40%-50%),48 as the risk of GVHD outweighs the benefit for other hematologic malignancies.

Lenalidomide posttransplant maintenance as monotherapy caused excessive acute GVHD (aGVHD) (60% grade III-IV GVHD within 2 cycles of therapy).49 Lenalidomide was then tested in combination with azacitidine in the phase 1 VIOLA trial, which showed only a 10% rate of aGVHD.50 The subsequent phase 2 Azalena trial confirmed the safety of lenalidomide and azacitidine when combined with DLI, with an ORR of 56% and median OS of 21 months in relapsed AML/MDS after alloSCT.51

IFN-α has been used to potentiate the effect of DLI in CML.52 In a recent phase 1/2 trial of pegylated interferon-2α in combination with DLI, GVHD incidence was relatively high (62%) with 2-year OS and PFS of 31% and 24%, respectively.53 Patients who developed GVHD survived longer than patients without GVHD (median OS 284 vs 43 days), suggesting a link between GVHD and GVL in this approach.

IFN-γ has been suggested as a rational strategy for potentiating GVL in myeloblastic leukemias based on preclinical studies showing that IFN-γ restores HLA expression on myeloid blasts after alloSCT.54,55,56 A phase 2 trial evaluating the safety of IFN-γ and DLI for posttransplant relapse is ongoing (NCT06529731).

Bi-specific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) are approved to treat B-cell malignancies. Blinatumomab was reported to safely salvage patients with relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) after alloSCT, achieving a 45% CR rate within 2 cycles and a 36% OS at 1 year.

CLINICAL CASE 2 (continued)

The patient received reinduction therapy with fludarabine and cytarabine and achieved an MRD-negative CR. She received DLI with recovery of donor T-cell chimerism. She subsequently developed mild skin and genital chronic GVHD, which was controlled with topical therapies. She has remained in NPM1-negative CR for 2 years.

CLINICAL CASE 3: WHAT IS THE ROLE OF SECOND ALLOGENEIC STEM CELL TRANSPLANTATION FOR RELAPSE?

A 36-year-old man with high-risk MDS with monosomy 7 and an EZH2 mutation (R-IPSS score 5.2) received a haploidentical alloSCT with myeloablative conditioning and PTCy. His BM showed detectable MRD by flow cytometry at 6 months after transplant. He received decitabine and venetoclax for 5 cycles; treatment was held for 3 months due to preseptal cellulitis and fungal pneumonia. A subsequent BM showed evolution to AML with 20% myeloblasts and new mutations (ASXL1, NF1, and GATA2) with 81% donor chimerism. He was treated with CPX (cytarabine and daunorubicin) liposome-351; a posttreatment BM sample had 2.2% residual abnormal blasts with 97% donor chimerism.

Second allogeneic stem cell transplantation

HSCT2 is a salvage option for physically fit patients, particularly those who have relapsed more than 6 months after the first alloSCT and achieved CR after salvage therapy with no prior high-grade GVHD.57,58 A retrospective study reported that AML/MDS patients who underwent HSCT2 had significantly higher 5-year OS rates (26%) than those who did not (7%).59 Moreover, survival after HSCT2 has improved over the past 2 decades, particularly in younger patients, whose 2-year OS is reported to be around 30%.60

The benefit of using the same or a different donor for HSCT2 is still unclear. Theoretically, a different HLA-matched donor could target different minor histocompatibility antigens. Large cohort studies, however, showed comparable outcomes in HSCT2 using the same donors vs different donors.58,61 Switching to a different haploidentical donor enables the targeting of mismatched HLA molecules, which could enable GVL.62 A retrospective registry analysis did not reveal the clinical benefits of using a new haploidentical donor in HSCT2. Rather, a switch was associated with higher NRM.63 Using HLA-LOH information to guide optimal donor selection for HSCT2 is biologically reasonable, so prospective studies are required to validate the utility of HLA-LOH for second donor selection.

Adoptive cell therapy

Donor-derived adoptive cell therapies have a potential role in preventing or treating posttransplant relapse. Donor-derived CD19 CAR-Ts (chimeric antigen receptor T-cells) induced deep and durable remissions without GVHD in relapsed B-ALL.64,65 When infused prophylactically, donor-derived anti-WT1 T-cell receptor-transduced T-cells (TCR-T) achieved 100% relapse-free survival at 3 years.66 Donor-derived multiple leukemia antigen-specific T-cells (mLSTs) were safely infused as adjuvant therapy prophylactically or for relapsed patients who achieved CR after salvage therapy with 2-year OS of 77%.67 More recently, TCR-T targeting the minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1 TCR-T was tested in patients with relapsed leukemia/MDS occurring after alloSCT; this was safe with a preliminary efficacy signal.68 Clinical trials testing a wide spectrum of donor-derived adoptive cellular therapies are expected to launch in the coming years (Table 3).

Clinical trials of cellular therapies to treat or prevent posttransplant relapse

| Trial name or ClinicalTrials.gov ID . | Investigational agent . | Disease . | Treatment setting . | Clinical endpoint . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GALAXY33 NCT05662904 | CRISPR/Cas9-based CD33 inactivated HSC+gemtuzumab | Relapsed CD33+AML after alloSCT | Salvage | Engraftment of gene-edited HSC |

| NCT05015426 | Gamma Delta T-cell | High-risk of AML recurrence after alloSCT | Prophylaxis | MTD Leukemia-free survival |

| KDS-1001 NCT05115630 | Off-the-shelf Third-party NK cells | AML, MDS, CML | Prophylaxis | NK cell related toxicities OS/DFS/GRFS |

| VCAR33 NCT05984199 | Donor-derived anti-CD33 CAR-T | Relapsed AML after HLA matched alloSCT | Salvage | DLT Response rate, GVHD, OS, PFS |

| AMpLify NCT06128044 | CRISPR-edited Allogeneic anti-CLL-1 CAR-T (CB-012) | Relapsed or refractory AML | Salvage | DLT ORR |

| NCT05473910 | Genetically engineered donor-derived T-cells targeting HA-1 (TSC-100) and HA-2 (TSC-101) | AML, MDS, ALL following haploidentical donor alloSCT | Prophylaxis | DLT OS, DFS, relapse rate |

| Trial name or ClinicalTrials.gov ID . | Investigational agent . | Disease . | Treatment setting . | Clinical endpoint . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GALAXY33 NCT05662904 | CRISPR/Cas9-based CD33 inactivated HSC+gemtuzumab | Relapsed CD33+AML after alloSCT | Salvage | Engraftment of gene-edited HSC |

| NCT05015426 | Gamma Delta T-cell | High-risk of AML recurrence after alloSCT | Prophylaxis | MTD Leukemia-free survival |

| KDS-1001 NCT05115630 | Off-the-shelf Third-party NK cells | AML, MDS, CML | Prophylaxis | NK cell related toxicities OS/DFS/GRFS |

| VCAR33 NCT05984199 | Donor-derived anti-CD33 CAR-T | Relapsed AML after HLA matched alloSCT | Salvage | DLT Response rate, GVHD, OS, PFS |

| AMpLify NCT06128044 | CRISPR-edited Allogeneic anti-CLL-1 CAR-T (CB-012) | Relapsed or refractory AML | Salvage | DLT ORR |

| NCT05473910 | Genetically engineered donor-derived T-cells targeting HA-1 (TSC-100) and HA-2 (TSC-101) | AML, MDS, ALL following haploidentical donor alloSCT | Prophylaxis | DLT OS, DFS, relapse rate |

CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CRISPR, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; DLT, dose limiting toxicity; GRFS, GVHD-free relapse-free survival; MTD, maximum tolerated dose.

CLINICAL CASE 3 (continued)

The patient received HSCT2 from a haploidentical donor who does not share haplotypes with his original donor using a myeloablative conditioning regimen with PTCy. He has been in MRD-negative CR with full-donor chimerism for 6 months without GVHD.

Conclusion

Current evidence is insufficient to provide optimal posttransplant approaches for every patient. Prospective, well-controlled studies are critically needed to investigate new strategies for risk-adapted prophylaxis or effective salvage therapies for posttransplant relapse. Clinical trials should always be considered for patients at high risk for or who have overt relapse.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Emily Geramita: no competing financial interests to declare.

Jing-Zhou Hou: no competing financial interests to declare.

Warren D. Shlomchik is a co-founder, option holder, and paid consultant for Bluesphere Bio. Warren D. Shlomchik is also an option holder and consultant for Orca Bio.

Sawa Ito has received the research funding from BlueSphere Bio.

Off-label drug use

Emily Geramita: Nothing to disclose.

Jing-Zhou Hou: Nothing to disclose.

Warren D. Shlomchik: Nothing to disclose.

Sawa Ito: Nothing to disclose.