Abstract

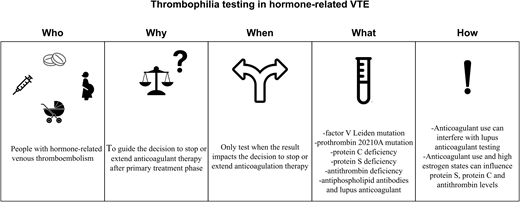

Hormone-related venous thromboembolism (VTE) is common and entails scenarios in which VTE occurs during exposure to exogenous or endogenous female sex hormones, typically estrogen and progestogen. For the management of hormone-related VTE, it is important to realize that many patients use these hormones for a vital purpose often strongly related to the patient's well-being and quality of life. In this review we discuss clinical cases of VTE related to hormonal contraceptive use and pregnancy to illustrate key considerations for clinical practice. We cover practice points for primary VTE treatment and detail the evidence on the risk of recurrent VTE and bleeding in this population. The potential value of thrombophilia testing is described, including “who, why, when, what, and how.” We also discuss key aspects of shared decision-making for anticoagulant duration, including a reduced-dose anticoagulant strategy in hormone-related VTE.

Learning Objectives

Identify key aspects of clinical practice in hormone-related VTE

Appreciate the “who, why, when, what, and how” of thrombophilia testing in hormone-related VTE

Explain key aspects of shared decision-making on anticoagulant treatment in hormone-related VTE

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 24-year-old woman was referred to our outpatient thrombosis service by her primary care provider because of pain and swelling of the right leg. A compression ultrasound confirmed the diagnosis of proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the popliteal and femoral vein. She had been immobilized during the past 3 weeks due to a lower-leg injury sustained during her work as a firefighter. She had no family history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and was otherwise healthy. She had been using combined oral contraceptives for over 1 year. She was started on apixaban at 10 mg twice daily for the first 7 days followed by 5 mg twice daily and continued the use of combined oral contraceptives. She was also prescribed a knee-high therapeutic elastic compression stocking class 3.

Hormone-related VTE

Hormone-related VTE is common and entails scenarios in which VTE occurs during changes in endogenous hormones or hormonal use known to be associated with an increased thrombotic risk. Most evidence on exogenous hormone use and VTE risk comes from studies on hormonal contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy.1 It has been well established that combined oral contraceptives induce procoagulant changes and are associated with an increased risk of VTE and that this risk depends on both the dose of estrogen and the type and dose of progestogen (Table 1).2 Moreover, we consider combined contraceptive use a contributing factor to the occurrence of a VTE, regardless of duration of use. Although a so-called starter effect of VTE risk with combined oral contraceptives is present (meaning that the relative risk (RR) for VTE is higher in the first 6-12 months of use than thereafter), an increased VTE risk persists over time.2

Commonly used hormonal contraceptives and associated VTE risk

| Hormonal contraceptive type . | VTE risk (RR, 95% CI), compared with nonusers . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|

| Does not increase VTE risk | ||

| Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device | 0.6 (0.2-1.5) | 30 |

| Low-dose progestin pill | 0.9 (0.6-1.5) | 30 |

| Uncertain VTE risk | ||

| Etongestrel birth control implant | 1.4 (0.6-3.4) | 31 |

| Increases VTE risk | ||

| Combined oral contraceptives | ||

| Ethinylestradiol (30-40 µg)/ levonorgestrel | 2.9 (2.2-3.8) | 32 |

| Ethinylestradiol (30-40 µg) desogestrel | 6.6 (5.6-7.8) | 32 |

| Ethinylestradiol (30-40 µg)/ drospirenone | 6.4 (5.4-7.5) | 32 |

| Combined contraceptive vaginal ring | 6.5 (4.7 to 8.9) | 31 |

| Progestin-only preparations | ||

| Progestin-only injections (DMPA) | 2.7 (1.3-5.5) | 30 |

| High-dose progestin pillsa | 5.9 (1.2-30.1) | 33 |

| Hormonal contraceptive type . | VTE risk (RR, 95% CI), compared with nonusers . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|

| Does not increase VTE risk | ||

| Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device | 0.6 (0.2-1.5) | 30 |

| Low-dose progestin pill | 0.9 (0.6-1.5) | 30 |

| Uncertain VTE risk | ||

| Etongestrel birth control implant | 1.4 (0.6-3.4) | 31 |

| Increases VTE risk | ||

| Combined oral contraceptives | ||

| Ethinylestradiol (30-40 µg)/ levonorgestrel | 2.9 (2.2-3.8) | 32 |

| Ethinylestradiol (30-40 µg) desogestrel | 6.6 (5.6-7.8) | 32 |

| Ethinylestradiol (30-40 µg)/ drospirenone | 6.4 (5.4-7.5) | 32 |

| Combined contraceptive vaginal ring | 6.5 (4.7 to 8.9) | 31 |

| Progestin-only preparations | ||

| Progestin-only injections (DMPA) | 2.7 (1.3-5.5) | 30 |

| High-dose progestin pillsa | 5.9 (1.2-30.1) | 33 |

Are typically used for gynecological indications other than contraception.

DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; RR, risk ratio.

The relationship between endogenous sex hormones and VTE risk is exemplified during pregnancy. During pregnancy an increased VTE risk is the result of procoagulant changes, stasis, and compression of the deep veins due to enlargement of the uterus (most importantly enhanced compression of the left iliac vein between the right iliac artery and lumbar vertebrae) and endothelial damage during delivery.3 Other common clinical scenarios of hormone-related VTE include assisted reproductive technology, hormone therapy in oncology, and gender-affirming hormone therapy (Table 2). Here we use the example of VTE related to the use of combined hormonal contraceptives and to pregnancy to discuss key considerations for clinical practice—ie, the risk of VTE recurrence, duration and intensity of anticoagulant therapy, and role of thrombophilia testing.

Common clinical scenarios of hormone-related VTE and key clinical considerations

| Clinical setting . | Key clinical considerations . | Further reading . |

|---|---|---|

| Hormonal contraceptives | • after start of anticoagulant therapy, the risk of abnormal uterine bleeding/heavy menstrual bleeding is high, and cessation of hormonal contraceptives likely further increases bleeding • need for adequate contraception during oral anticoagulant treatment • indications for use not only include prevention of pregnancy but may also include polycystic ovary syndrome, abnormal uterine bleeding, and endometriosis • indication for thromboprophylaxis in future pregnancy | 1,34 |

| Assisted reproductive technology | • desire for parenthood is central for many patients | 18 |

| Pregnancy and postpartum period | • manage health of both mother and unborn child/newborn • low-molecular-weight heparins are the first choice of treatment during pregnancy; very common side effects include bruising and skin allergies • for the prevention and management of VTE, DOACs and VKAsa are contraindicated during pregnancy due to concerns for the unborn child • challenges of anticoagulant management around delivery and neuraxial anesthesia • some anticoagulants are contraindicated during breastfeeding • consequences for thromboprophylaxis in future pregnancy | 18 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | • indications for use are generally well-being and quality of life | 34 |

| Gender-affirming therapy | • indication for use is crucial for well-being and quality of life | 35 |

| Hormone therapy in oncology | • likely has an impact on the oncological management plan and prognosis | 36 |

| Clinical setting . | Key clinical considerations . | Further reading . |

|---|---|---|

| Hormonal contraceptives | • after start of anticoagulant therapy, the risk of abnormal uterine bleeding/heavy menstrual bleeding is high, and cessation of hormonal contraceptives likely further increases bleeding • need for adequate contraception during oral anticoagulant treatment • indications for use not only include prevention of pregnancy but may also include polycystic ovary syndrome, abnormal uterine bleeding, and endometriosis • indication for thromboprophylaxis in future pregnancy | 1,34 |

| Assisted reproductive technology | • desire for parenthood is central for many patients | 18 |

| Pregnancy and postpartum period | • manage health of both mother and unborn child/newborn • low-molecular-weight heparins are the first choice of treatment during pregnancy; very common side effects include bruising and skin allergies • for the prevention and management of VTE, DOACs and VKAsa are contraindicated during pregnancy due to concerns for the unborn child • challenges of anticoagulant management around delivery and neuraxial anesthesia • some anticoagulants are contraindicated during breastfeeding • consequences for thromboprophylaxis in future pregnancy | 18 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | • indications for use are generally well-being and quality of life | 34 |

| Gender-affirming therapy | • indication for use is crucial for well-being and quality of life | 35 |

| Hormone therapy in oncology | • likely has an impact on the oncological management plan and prognosis | 36 |

VKAs are considered on a case-by-case basis during pregnancy in women with mechanical heart valves and high thrombotic risk.

Initial anticoagulant management and special considerations for clinical practice

The initial management of hormone-related VTE does not differ from the general approach and includes initiation of therapeutic-dose anticoagulants.4 When taking care of patients with hormone-related VTE, it is important to realize that many patients use hormones for a vital purpose that is often strongly related to the patient's well-being and quality of life. Therefore, the management of hormone-related VTE entails key clinical considerations that extend beyond the general concepts of VTE management (Table 2). For women with hormonal contraceptive–related VTE who need to use anticoagulant therapy, an important concern is the risk of abnormal uterine bleeding, including heavy menstrual bleeding, during anticoagulant treatment.5-7 Recent cohort studies have reported heavy menstrual bleeding in up to 70% of premenopausal women starting direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).8,9 Heavy menstrual bleeding is associated with interference in daily life, diminished quality of life, and the risk of medical interventions and hospitalization.8,9 For our patient of case 1, we advised continuation of hormonal contraceptives during the initial anticoagulant treatment phase. The advantages of this strategy include the prevention of potential heavy menstrual bleeding due to hormone withdrawal and continued adequate contraception during anticoagulant treatment. Two studies underline the safety of this strategy in terms of recurrence of VTE. A post-hoc analysis of the phase 3 studies evaluating the efficacy of rivaroxaban vs warfarin for acute VTE demonstrated that the risk of VTE recurrence was not higher in women who used hormonal contraceptives while on anticoagulant treatment (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.2-1.4).10 Similar findings were observed in a follow-up study of 650 premenopausal women with a first VTE who were treated with a vitamin K antagonist (VKA).11 The risk of recurrence was not higher in those who used hormonal contraceptives on anticoagulant treatment (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.1-8.2).11

Another important consideration that affects many women with a hormonal contraceptive–related VTE concerns counseling on thromboprophylaxis in future pregnancies. Women with a history of VTE have a 6% to 10% risk of recurrence during pregnancy and the postpartum period in the absence of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis.12-15 This risk is influenced by the circumstances during the initial VTE event, in which the risk of pregnancy-related VTE is highest among women with a first VTE related to hormone use or pregnancy.13,15-17 Based on these estimates, all women with a previous hormone-related VTE are at substantial risk during future pregnancy, and thromboprophylaxis throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period is recommended.18 The optimal dose of thromboprophylaxis during pregnancy and a postpartum group was evaluated in the Highlow randomized controlled trial.19 In pregnant women with a history of VTE who did not use continuous anticoagulation, the efficacy and safety of weight-adjusted intermediate-dose and fixed low-dose low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) were compared.19 During pregnancy and the postpartum period, VTE occurred in 11 (2%) of 555 women in the weight-adjusted intermediate-dose group and in 16 (3%) of 555 in the fixed low-dose group: the RR was 0.69 (95% CI, 0.32-1.47).19 When separating the analyses by pregnancy and the postpartum period, a recurrence occurred antepartum in 5 (1%) women in the intermediate-dose group and in 5 (1%) women in the low-dose group. In the postpartum period, this occurred in 6 (1%) and 11 (2%) women in the intermediate- and low-dose group, respectively.19 Taken together, based on the available evidence we counsel women with an indication for thromboprophylaxis to use low-dose LMWH during pregnancy and intermediate-dose LMWH during the 6 weeks post partum.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The swelling and pain of the calf subsided, and the prescribed knee-high compression stocking was well tolerated. After 3 months of primary anticoagulant treatment, her combined oral contraceptives were switched to a progestogen-containing intrauterine device. After discussion with the patient, thrombophilia testing was performed, and the results came back negative. Anticoagulants were stopped after shared decision-making, during which the recurrence risk of anticoagulant therapy (as determined by the provoked nature of the event with the subsequent cessation of combined contraceptives and the absence of thrombophilia) was balanced against potential anticoagulant-related bleeding risks (also given her work) and the burden of treatment.

Prognosis

After completion of the primary anticoagulant treatment phase of 3 months, a decision must be made to continue or stop anticoagulants. Shared decision-making with the patient to weigh the risks of recurrent VTE and bleeding and the burden of treatment is preferred. In general the risk of recurrent VTE after the cessation of anticoagulant therapy is related to the presence and strength of a risk factor at the time of the initial event. The stronger the risk factor, the lower the risk of recurrence, provided that the risk factor is transient.20 As an example, major surgery is considered a major VTE risk factor with a low risk of future VTE recurrence.21 Nonsurgical major risk factors, such as confinement to a bed in a hospital for at least 3 days with an acute illness or a leg injury associated with decreased mobility for at least 3 days, as well as hormone use or pregnancy and postpartum period, are intermediately strong risk factors with an intermediate risk of recurrent VTE.21 Patients with an unprovoked VTE (ie, no apparent risk factors at the time of the event) have the highest risk of recurrence. Hormone use or pregnancy/postpartum- related events seem to be intermediately strong risk factors with respect to the risk of recurrent VTE.22

Several risk-assessment models have been developed with the aim of informing personalized risk estimates of both recurrence and bleeding and to aid the clinician and patient in the decision-making process.23,24 It should be noted that before these models are implemented in clinical practice, thorough validation studies and, ideally, clinical trials are needed to demonstrate the efficacy of these models.23,24

When deciding on the duration of anticoagulant therapy, ideally the absolute risks of VTE recurrence and bleeding are known in the following scenarios: (1) stopping anticoagulants (2) continuing with anticoagulants in a reduced dose, and (3) continuing anticoagulants in a full dose. Available estimates for the risk of VTE recurrence and bleeding in hormonal contraceptive–related VTE are depicted in Table 3. The available evidence on risk of recurrence after discontinuing hormonal contraceptives has recently been summarized in 2 systematic reviews and meta-analyses (of which several included studies overlapped).25,26 In the first study, the pooled recurrence risk was 1.6 per 100 person-years (14 studies, including 3112 women) with a similar recurrence risk of 1.3 per 100 patient-years when only studies in which women definitely stopped hormones after the first VTE were included.25 In the second study, the pooled recurrence rate was similar: 1.2 events per 100 person-years (19 studies, 1537 women).26 This recurrence rate appears low and reassuring; however, as these are mostly young patients, the additive risk over the course of several years should be considered. Risk assessment is crucial for identifying women at high risk of VTE recurrence, for whom continuing anticoagulation treatment might be beneficial. To this end the recently published American Society of Hematology (ASH) Guideline on Thrombophilia Testing has suggested a strategy based on thrombophilia testing.27

Estimates of VTE recurrence and bleeding incidence relevant to hormone-related VTE

| Clinical context . | Study type . | Absolute risk estimates . | Comments . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE recurrence risk | ||||

| Women (all ages, various VTE types) • Stopped anticoagulants | Individual patient data meta-analysis including data (n = 1268) | VTE recurrence: 5.3% (95% CI, 4.1-6.7) after 1 year 9.1% (95% CI, 7.3-11.3) after 3 years | In this study hormone-related VTE were grouped with unprovoked VTE. | 37 |

| Women with a first hormonal- contraceptive–related VTE, • Stopped anticoagulants • Stopped hormonal contraceptives | Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses (n = 3 112 and n = 1537) | VTE recurrence: 1.3 (95% CI, 0.7-2.4) and 1.2 (95% CI, 0.9-1.6) per 100 person-years | Several studies in these systematic reviews overlapped. | 25,26 |

| Women with a first VTE • Stopped anticoagulant therapy (VKA) • Started or continued hormonal contraceptives | Cohort study (n = 650) | VTE recurrence: 4.8 (95% CI, 2.3-8.9) per 100 person-years, vs 1.5 (95% CI, 1.1-2.3) among those who did not use combined hormonal contraceptives | Similar results for women using only combined hormonal contraceptives during the first VTE and those who had an additional otherwise provoking factor (eg, surgery, cast, immobility, etc). | 11 |

| Women and men (all ages) with a provoked VTE by a nonsurgical risk factor • Stopped anticoagulant therapy | Systematic review of cohort studies (n = 509) | VTE recurrence: 4.2 (95% CI, 2.8-5.6) per 100 person-years | Estimate can be used to approximate VTE recurrence risk after a pregnancy-related VTE, no direct data available in this group. | 38 |

| Bleeding risk | ||||

| Women and men (all ages, unprovoked VTE) • During extended oral anticoagulant therapy with DOAC | Systematic review and meta-analyses (n = 7220) | Major bleeding: 1.1 events (95% CI, 0.7-1.6 events) per 100 person-years | No data on reduced-dose strategy. No data on heavy menstrual bleeding. | 39 |

| Women and men (all ages, unprovoked VTE) • After stopping anticoagulant therapy | Systematic review and meta-analyses (n = 8740) | Major bleeding: 0.4 events (95% CI, 0.2-0.5) per 100 person- years | 40 | |

| Clinical context . | Study type . | Absolute risk estimates . | Comments . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE recurrence risk | ||||

| Women (all ages, various VTE types) • Stopped anticoagulants | Individual patient data meta-analysis including data (n = 1268) | VTE recurrence: 5.3% (95% CI, 4.1-6.7) after 1 year 9.1% (95% CI, 7.3-11.3) after 3 years | In this study hormone-related VTE were grouped with unprovoked VTE. | 37 |

| Women with a first hormonal- contraceptive–related VTE, • Stopped anticoagulants • Stopped hormonal contraceptives | Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses (n = 3 112 and n = 1537) | VTE recurrence: 1.3 (95% CI, 0.7-2.4) and 1.2 (95% CI, 0.9-1.6) per 100 person-years | Several studies in these systematic reviews overlapped. | 25,26 |

| Women with a first VTE • Stopped anticoagulant therapy (VKA) • Started or continued hormonal contraceptives | Cohort study (n = 650) | VTE recurrence: 4.8 (95% CI, 2.3-8.9) per 100 person-years, vs 1.5 (95% CI, 1.1-2.3) among those who did not use combined hormonal contraceptives | Similar results for women using only combined hormonal contraceptives during the first VTE and those who had an additional otherwise provoking factor (eg, surgery, cast, immobility, etc). | 11 |

| Women and men (all ages) with a provoked VTE by a nonsurgical risk factor • Stopped anticoagulant therapy | Systematic review of cohort studies (n = 509) | VTE recurrence: 4.2 (95% CI, 2.8-5.6) per 100 person-years | Estimate can be used to approximate VTE recurrence risk after a pregnancy-related VTE, no direct data available in this group. | 38 |

| Bleeding risk | ||||

| Women and men (all ages, unprovoked VTE) • During extended oral anticoagulant therapy with DOAC | Systematic review and meta-analyses (n = 7220) | Major bleeding: 1.1 events (95% CI, 0.7-1.6 events) per 100 person-years | No data on reduced-dose strategy. No data on heavy menstrual bleeding. | 39 |

| Women and men (all ages, unprovoked VTE) • After stopping anticoagulant therapy | Systematic review and meta-analyses (n = 8740) | Major bleeding: 0.4 events (95% CI, 0.2-0.5) per 100 person- years | 40 | |

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 37-year-old woman presented with progressive dyspnea and chest pain during the 28th week of her third pregnancy. There were no clinical signs of DVT, and her D-dimer level was 1812 ng/mL. Computed tomographic angiography revealed bilateral segmental pulmonary emboli, and she was started on therapeutic-dose LMWH. She had no relevant personal medical history but reported that her grandmother had experienced DVT after surgery at the age of approximately 50 years. Although she was planned for delivery at 37 + 0 weeks of gestation, signs of delivery occurred at 36 + 5 weeks, and she temporarily stopped LMWH. She had an uncomplicated vaginal delivery without neuraxial anesthesia and an estimated blood loss of 500 mL, and she resumed therapeutic-dose LMWH 24 hours after delivery. As she experienced several months of self-injections as burdensome and she breastfed her child, she was switched to a VKA with a target international normalized ratio (INR) of 2 to 3 until 6 weeks post partum. At that time we discussed her risk of recurrent VTE if anticoagulation was stopped, as well as the burden and potential risk of bleeding with continued anticoagulant treatment (Box 1). We noted the paucity of data on the risk of VTE recurrence after a pregnancy-related event, which is currently considered an intermediate risk factor. We discussed the possibility of thrombophilia testing and if and how test results might help to decide whether to stop or continue anticoagulant treatment. She opted for thrombophilia testing, which she underwent after temporarily switching VKA to LMWH. The results showed heterozygosity for a prothrombin G20210A mutation, with the rest of the panel negative, and a shared decision was made to continue anticoagulant use. The importance of adequate contraceptive measures during anticoagulant therapy was discussed, and she opted for an intrauterine levonorgestrel-releasing device. At 3 months post partum she had stopped breastfeeding, and the VKA was switched to a factor Xa inhibitor at a reduced dose, as she had completed a total of 6 months of primary anticoagulant treatment. We continue to evaluate the benefits and harms of this anticoagulant strategy with the patient annually.

Clinical reasoning in clinical case 2

| In patients with a pregnancy-related or postpartum-related VTE, data on the risk of VTE recurrence are scarce. |

| + |

| These events are classified among the intermediate-risk provoking factors, for which the decision to stop or extend anticoagulant therapy is generally more challenging than events provoked by major surgery (ie, low VTE recurrence risk, most patients will stop anticoagulant therapy) or unprovoked (ie, high VTE recurrence risk, most patients will continue) events. |

| + |

| Given the multicausal nature of VTE, most patients with intermediate-risk events will have other intrinsic (eg, inherited) or extrinsic VTE risk factors. Recognizing the limitations of the available evidence, the presence of inherited thrombophilia in this patient group is associated with a higher VTE recurrence risk. |

| + |

| In the ASH guideline on thrombophilia testing, a modeling approach was used to estimate the net benefit (risk of recurrent VTE and bleeding) of a thrombophilia-screening strategy followed by a treatment or prevention strategy based on the result of the test. Using this approach, and acknowledging the methodological limitations of this approach, a thrombophilia testing strategy may be beneficial for patients with a VTE provoked by an intermediate-risk factor. |

| ↓ |

| In this case we discussed the scarcity of the available data and the possibility of thrombophilia testing and asked: Do test results help to decide whether to stop or continue anticoagulant treatment and if so, how? |

| In patients with a pregnancy-related or postpartum-related VTE, data on the risk of VTE recurrence are scarce. |

| + |

| These events are classified among the intermediate-risk provoking factors, for which the decision to stop or extend anticoagulant therapy is generally more challenging than events provoked by major surgery (ie, low VTE recurrence risk, most patients will stop anticoagulant therapy) or unprovoked (ie, high VTE recurrence risk, most patients will continue) events. |

| + |

| Given the multicausal nature of VTE, most patients with intermediate-risk events will have other intrinsic (eg, inherited) or extrinsic VTE risk factors. Recognizing the limitations of the available evidence, the presence of inherited thrombophilia in this patient group is associated with a higher VTE recurrence risk. |

| + |

| In the ASH guideline on thrombophilia testing, a modeling approach was used to estimate the net benefit (risk of recurrent VTE and bleeding) of a thrombophilia-screening strategy followed by a treatment or prevention strategy based on the result of the test. Using this approach, and acknowledging the methodological limitations of this approach, a thrombophilia testing strategy may be beneficial for patients with a VTE provoked by an intermediate-risk factor. |

| ↓ |

| In this case we discussed the scarcity of the available data and the possibility of thrombophilia testing and asked: Do test results help to decide whether to stop or continue anticoagulant treatment and if so, how? |

Role of thrombophilia testing

Recently, ASH guidelines were published on the role of thrombophilia testing in the management and prevention of VTE.27 In this guideline, modeling was used to determine the added value of thrombophilia testing in several clinical scenarios, including hormone-related VTE. The factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A mutations, hereditary deficiencies of protein C (PC), protein S (PS), and antithrombin (AT), and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant, anti-ß2-glycoprotein-1 immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM antibodies, anticardiolipin IgG and IgM antibodies) were included in the thrombophilia panel based on their robust association with a first episode of VTE.27 For each type of thrombophilia, data on the prevalence and associated VTE risk were used to estimate the risk of recurrent VTE in those with and without thrombophilia (Table 4). The median prevalence of any thrombophilia (ie, at least 1 of the included thrombophilia types in the panel) among patients with VTE in the included studies was 38.0% (min-max, 21.6-59.5).27 Subsequently, the net benefit of a thrombophilia-screening strategy, including VTE prevented/tolerated and bleeding prevented/tolerated, was evaluated based on the assumption that thrombophilia testing was followed by continuing (in the case of a positive test) or stopping (in the case of a negative test) anticoagulation. In other words, thrombophilia testing was only suggested in clinical situations in which the result of the test would change management. To illustrate, in patients with unprovoked VTE, testing was not suggested, as the risk for recurrent VTE in both scenarios (ie, positive or negative thrombophilia screening) was deemed too high to discontinue anticoagulant treatment in most patients.4 In VTE provoked by a major risk factor such as surgery, testing was also not suggested as the risk for recurrent VTE was too low to continue anticoagulant therapy after primary treatment, regardless of thrombophilia status.4

Estimated prevalence of thrombophilia in patients with VTE and risk of recurrent VTE associated with the presence of thrombophilia

| Type of thrombophilia . | Prevalence, median % (min-max) . | RR for VTE recurrence, positive vs negative (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Any thrombophilia | 38.0 (21.6-59.5) | 1.65 (1.28-2.47) |

| Factor V Leiden mutation, homozygous | 1.5 (0.3-3.1) | 2.10 (1.09-4.06) |

| Factor V Leiden mutation, heterozygous | 17.5 (4.1-34.8) | 1.36 (1.19-1.57) |

| Prothrombin G20210A gene mutationa | 6.1 (1.4-16.3) | 1.34 (1.05-1.71) |

| AT deficiency | 2.2 (0.2-8.7) | 2.07 (1.50-2.87) |

| PC deficiency | 2.5 (0.7-8.6) | 2.13 (1.26-3.59) |

| PS deficiency | 2.3 (0.7-7.3) | 1.30 (0.87-1.94) |

| AT, PC, or PS deficiency | 7.0 (2.5-18.4) | 1.62 (1.17-2.23) |

| Antiphospholipid antibodiesb | 9.7 (1.9-19.4) | 1.92 (0.99-3.72) |

| Type of thrombophilia . | Prevalence, median % (min-max) . | RR for VTE recurrence, positive vs negative (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|

| Any thrombophilia | 38.0 (21.6-59.5) | 1.65 (1.28-2.47) |

| Factor V Leiden mutation, homozygous | 1.5 (0.3-3.1) | 2.10 (1.09-4.06) |

| Factor V Leiden mutation, heterozygous | 17.5 (4.1-34.8) | 1.36 (1.19-1.57) |

| Prothrombin G20210A gene mutationa | 6.1 (1.4-16.3) | 1.34 (1.05-1.71) |

| AT deficiency | 2.2 (0.2-8.7) | 2.07 (1.50-2.87) |

| PC deficiency | 2.5 (0.7-8.6) | 2.13 (1.26-3.59) |

| PS deficiency | 2.3 (0.7-7.3) | 1.30 (0.87-1.94) |

| AT, PC, or PS deficiency | 7.0 (2.5-18.4) | 1.62 (1.17-2.23) |

| Antiphospholipid antibodiesb | 9.7 (1.9-19.4) | 1.92 (0.99-3.72) |

Also referred to as factor II mutation; separate estimates for heterozygous/homozygous mutations are not available.

Lupus anticoagulant, anti–ß2-glycoprotein-1 IgG and IgM antibodies, anticardiolipin IgG and IgM antibodies.

Adapted with permission from Middeldorp et al.27

The suggestions regarding thrombophilia testing that apply to people with hormone-related VTE are summarized in Table 5 and depict the “who, why, when, what, and how” to test. The guideline panel emphasized that recommendations were conditional, that they were based on the necessity of using a modeling approach given the lack of direct evidence, and that most of the evidence was at high risk of bias.27 From a patient's perspective, conditional recommendations imply that most individuals in this situation want the suggested course of action, but many do not. From a clinician's perspective, different choices are appropriate for individual patients; clinicians must help each patient arrive at a management decision consistent with the patient's values and preferences.27

Suggested thrombophilia testing in hormone-related VTE: who, why, when, what and how to test?

| Who . | Why . | When . | What . | Howc . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE associated with combined oral contraceptives | Strategyb to guide the decision to stop or continue anticoagulant therapy after primary treatment phase; indefinite anticoagulant treatment for patients with thrombophilia is suggested. | Only test when, after shared decision-making, the result impacts the decision to stop or continue anticoagulation therapy. | Thrombophilia panel: • factor V Leiden mutation • prothrombin G20210A mutation • PC deficiency • PS deficiency • AT deficiency • antiphospholipid antibodies (LAC, anti-ß2- glycoprotein-I IgG and IgM antibodies, anticardiolipin IgG and IgM antibodies) | If on DOAC: • can influence LAC/PC/PSd/AT results • briefly interrupt or temporally switch to LMWH and test at anticoagulant trough | If on VKA: • can influence LAC/PS/PC results • switch to LMWH and test at anticoagulant trough | If on LMWH: test at anticoagulant trough |

| VTE provoked by pregnancy or 3-month postpartum period | ||||||

| VTE associated with assisted reproductive technologya | ||||||

| VTE associated with hormone replacement therapya | ||||||

| VTE associated with gender-affirming therapya | ||||||

| Who . | Why . | When . | What . | Howc . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE associated with combined oral contraceptives | Strategyb to guide the decision to stop or continue anticoagulant therapy after primary treatment phase; indefinite anticoagulant treatment for patients with thrombophilia is suggested. | Only test when, after shared decision-making, the result impacts the decision to stop or continue anticoagulation therapy. | Thrombophilia panel: • factor V Leiden mutation • prothrombin G20210A mutation • PC deficiency • PS deficiency • AT deficiency • antiphospholipid antibodies (LAC, anti-ß2- glycoprotein-I IgG and IgM antibodies, anticardiolipin IgG and IgM antibodies) | If on DOAC: • can influence LAC/PC/PSd/AT results • briefly interrupt or temporally switch to LMWH and test at anticoagulant trough | If on VKA: • can influence LAC/PS/PC results • switch to LMWH and test at anticoagulant trough | If on LMWH: test at anticoagulant trough |

| VTE provoked by pregnancy or 3-month postpartum period | ||||||

| VTE associated with assisted reproductive technologya | ||||||

| VTE associated with hormone replacement therapya | ||||||

| VTE associated with gender-affirming therapya | ||||||

Defined as a nonsurgical major transient risk factor.

In patients with VTE related to major surgery (who have a low VTE recurrence risk) or patients with unprovoked VTE (who have a high VTE recurrence risk), this strategy is not suggested as a thrombophilia testing strategy does not affect the decision to stop or continue anticoagulation therapy.

Applies to therapeutic-dosed anticoagulation; see also Table 5 and Favaloro et al41 for practical points.

DOAC use may influence PS activity levels; PS antigen measurements are not affected.

LAC, lupus anticoagulant.

Based on the ASH 2023 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: thrombophilia testing, adapted with permission from Middeldorp et al.27

The key challenge in deciding on extended anticoagulant therapy is balancing the trade-off between the risk of recurrent VTE events and the risk of bleeding while on anticoagulant treatment. Here, the thrombophilia testing strategy can inform on the risk of recurrence, as thrombophilia carriers have a somewhat higher risk than noncarriers. Of note, the balance in thrombosis and bleeding risks should be evaluated periodically and may be adjusted when, for instance, patient preference changes, bleeding occurs, or bleeding risk factors emerge.

If the decision to test for thrombophilia is made, practical points for testing thrombophilia should also be considered (Table 6). The role of testing for asymptomatic family members is beyond the scope of this review, and readers are referred to the ASH guideline for further reading.27

Practical points when testing thrombophilia

| Thrombophilia . | Type of test . | Practical points . |

|---|---|---|

| Inherited thrombophilia | ||

| Factor V Leiden mutation | Activated PC resistance screening testa | Can be influenced by acute thrombosis, high estrogen states (pregnancy, hormone use), coagulation factor deficiencies (eg, FVIII, FIX), the presence of lupus anticoagulant, and anticoagulant use |

| DNA test | Can be tested regardless of use of anticoagulants or hormonal status | |

| Prothrombin G20210A mutation | DNA test | Can be tested regardless of use of anticoagulants or hormonal status |

| PC deficiency | Typically chromogenic, ELISA or functional clotting-based assay | May be influenced by acute thrombosis, high estrogen states (pregnancy, hormone use), and anticoagulant use—interpret abnormal values with caution |

| PS deficiency | ||

| AT deficiency | ||

| Acquired thrombophilia, antiphospholipid antibodiesb | ||

| Lupus anticoagulant | Substantial variation among laboratories; typically includes a screening (eg, dilute Russell viper venom test or lupus anticoagulant-sensitive prothrombin time) and a confirmation test (eg, mixing or correction test) | Consult local laboratory for specifics, is generally influenced by anticoagulant use |

| Anti−ß2-glycoprotein-I IgG and IgM antibodies | Typically ELISA | Substantial variation in absolute cutoff values, consult local laboratory for specifics |

| Anticardiolipin IgG and IgM antibodies | Typically ELISA | Substantial variation in absolute cutoff values, consult local laboratory for specifics |

| Thrombophilia . | Type of test . | Practical points . |

|---|---|---|

| Inherited thrombophilia | ||

| Factor V Leiden mutation | Activated PC resistance screening testa | Can be influenced by acute thrombosis, high estrogen states (pregnancy, hormone use), coagulation factor deficiencies (eg, FVIII, FIX), the presence of lupus anticoagulant, and anticoagulant use |

| DNA test | Can be tested regardless of use of anticoagulants or hormonal status | |

| Prothrombin G20210A mutation | DNA test | Can be tested regardless of use of anticoagulants or hormonal status |

| PC deficiency | Typically chromogenic, ELISA or functional clotting-based assay | May be influenced by acute thrombosis, high estrogen states (pregnancy, hormone use), and anticoagulant use—interpret abnormal values with caution |

| PS deficiency | ||

| AT deficiency | ||

| Acquired thrombophilia, antiphospholipid antibodiesb | ||

| Lupus anticoagulant | Substantial variation among laboratories; typically includes a screening (eg, dilute Russell viper venom test or lupus anticoagulant-sensitive prothrombin time) and a confirmation test (eg, mixing or correction test) | Consult local laboratory for specifics, is generally influenced by anticoagulant use |

| Anti−ß2-glycoprotein-I IgG and IgM antibodies | Typically ELISA | Substantial variation in absolute cutoff values, consult local laboratory for specifics |

| Anticardiolipin IgG and IgM antibodies | Typically ELISA | Substantial variation in absolute cutoff values, consult local laboratory for specifics |

Activated PC resistance testing can be used as a screening test; confirmatory testing is done by DNA testing.

Also refer to guidance from the Scientific and Standardization Committee for lupus anticoagulant/antiphospholipid antibodies of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis and the 2023 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology Antiphospholipid Syndrome Classification Criteria.42,43

ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; F, factor.

CLINICAL CASE 3

A 31-year-old woman visited our outpatient clinic for follow-up after being diagnosed with acute proximal DVT of the left leg 3 weeks earlier at the emergency department. She had been started on apixaban per label, and although her symptoms had improved, she had still experienced occasional calf cramps. Her medical history revealed an appendectomy 12 years ago, and she had been diagnosed with endometriosis 2 years ago. The symptoms of endometriosis had had a substantial impact on her daily life, and she had undergone laparoscopic surgery 6 months earlier, after which she had started combined hormonal contraceptives. Since that time the symptoms of endometriosis had virtually resolved, and she discussed her hesitancy to change her hormonal endometriosis management with us. After consulting with her gynecologist, we discussed several options, including transdermal estrogen, nonhormonal therapies, and continuing the current hormonal contraceptives simultaneously with anticoagulant therapy. Her estimated bleeding risk was low, and she opted for continuing hormonal contraceptives with simultaneously continuing anticoagulant therapy. As there would be no management consequences, we did not discuss the possibility of thrombophilia testing. After 6 months of primary treatment, we discussed the option of a reduced-dose strategy, explicitly noting the scarcity of evidence in the context of continued hormone use. As she had not experienced any bleeding symptoms, the patient decided to continue full-dose anticoagulants as a secondary prevention. We continue to evaluate the benefits and harms of this anticoagulant strategy with the patient annually.

Duration of anticoagulation and special considerations for clinical practice

After 3 months of primary VTE treatment, a decision should be made to stop or continue anticoagulant use for secondary prevention.4 As illustrated by the clinical cases, in people with hormone-related VTE this decision deserves special considerations and requires shared decision-making. If the event was related to hormone use, hormonal alternatives that do not increase VTE risk need to be considered. If alternatives are available and chosen, a patient-centered discussion of thrombophilia testing can be considered. For a sizeable group of patients, including those with hormone replacement therapy and gender-affirming therapy, the patient's well-being and health rely substantially on continuing the hormone regimen. In such patients we consider, next to the option of nonthrombogenic hormonal alternatives, continuing both hormones and anticoagulant treatment. After the primary treatment phase, we consider the option of a reduced-dose strategy with a factor Xa inhibitor. For people with transient hormone use or pregnancy/postpartum-related VTE events using continued anticoagulation based on the presence of thrombophilia, we suggest a reduced-dose strategy after 6 months of primary treatment.28,29 For people continuing the use of hormones combined with continued anticoagulant therapy, no direct evidence for a dose reduction of factor Xa inhibitor is available, and we discuss this option on a case-by-case basis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Luuk J. J. Scheres: no competing financial interests to declare.

Saskia Middeldorp: Consultancy fees from Abbvie, Alveron, Astra Zeneca, Bayer (markets Rivaroxaban which is a Factor Xa inhibitor mentioned in the article), Hemab, Norgine, Sanofi and Viatris and Research funding from Synaspe.

Off-label drug use

Luuk J. J. Scheres: There is no off-label drug use to disclose.

Saskia Middeldorp: There is no off-label drug use to disclose.