Key Points

Depression was found in 35.2% of adult SCD patients and was strongly associated with worse physical and mental quality-of-life outcomes.

Total health care costs for adult SCD patients with depression were more than double those of SCD patients without depression.

Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a chronic, debilitating disorder. Chronically ill patients are at risk for depression, which can affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL), health care utilization, and cost. We performed an analytic epidemiologic prospective study to determine the prevalence of depression in adult patients with SCD and its association with HRQoL and medical resource utilization. Depression was measured by the Beck Depression Inventory and clinical history in adult SCD outpatients at a comprehensive SCD center. HRQoL was assessed using the SF36 form, and data were collected on medical resource utilization and corresponding cost. Neurocognitive functions were assessed using the CNS Vital Signs tool. Pain diaries were used to record daily pain. Out of 142 enrolled patients, 42 (35.2%) had depression. Depression was associated with worse physical and mental HRQoL scores (P < .0001 and P < .0001, respectively). Mean total inpatient costs ($25 000 vs $7487, P = .02) and total health care costs ($30 665 vs $13 016, P = .01) were significantly higher in patients with depression during the 12 months preceding diagnosis. Similarly, during the 6 months following diagnosis, mean total health care costs were significantly higher in depressed patients than in nondepressed patients ($13 766 vs $8670, P = .04). Depression is prevalent in adult patients with SCD and is associated with worse HRQoL and higher total health care costs. Efforts should focus on prevention, early diagnosis, and therapy for depression in SCD.

Introduction

Patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) experience recurrent acute painful episodes, and up to 30% experience chronic pain (defined as pain that persists for >3 months).1 Chronic pain is associated with depression and other psychological disorders.2-4 A high prevalence of depression has been reported in SCD patients compared with the general population.5,6 Patients with SCD and depression experience less favorable medical outcomes than patients without depression.7,8 Depression was found to be associated with frequent hospitalization for vaso-occlusive pain, more emergency room visits, and recurrent blood transfusion.9 Moreover, depression is associated with clinical complications,10 and in a study by Nadel and Portadin,11 50% of patients heralded depressive symptoms heralded painful episodes.

Recurrent pain, repeated hospitalization and organ damage related to disease complications, can negatively affect health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) outcomes in SCD. Previously, HRQoL outcomes were found to be worse in SCD patients than in unaffected individuals and closely resembled HRQoL outcomes of dialysis patients.12

Elderly patients with silent cerebral infarctions are at risk for depression.13,14 In SCD, cerebrovascular accidents and silent cerebral infarctions are serious complications15 that lead to neurocognitive deficits and learning difficulties.16,17 Thus, depression maybe associated with neurocognitive deficits in SCD.

The cost of medical care for patients with SCD is substantial. Data from a National Hospital Discharge Survey (1989-1993) and the 1992 Nationwide Inpatient Sample estimated the average direct cost per hospitalization (in 1996 dollars) to be $6300, and costs increased with age.18 The estimated total direct cost of hospitalizations per year for people with SCD was $475.2 million. The expected principal source of payment was a government program in 66% of hospitalizations, private insurance in 20%, self-payment in 7%, another source in 4%, and was not stated in 3%.18 More recently, the estimated total health care cost per year for children and adults with SCD in the United States was estimated at >$1.1 billion.19

In a general medical practice, depressed patients used significantly more health care resources than nondepressed patients.20 Further, the costs for both primary care physician visits and tests and consults ordered at those visits were 2 times higher in depressed patients than in nondepressed patients.19

A few studies have retrospectively evaluated health care and resource utilization and expenditures for SCD patients with depression.9,21,22 A recent systematic review found depression to be associated with higher health care utilization among patients with SCD,23 but little is known about its impact on health outcomes.

We hypothesize that depression in SCD is associated with lower HRQoL outcomes and higher health care utilization and cost. In this study, we report on the relationship between depression and clinical variables, HRQoL outcomes, and medical resource utilization in SCD.

Methods

Patients with SCD were approached during their regular clinic visits to the Duke Adult Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center. Over a 9-month period (February 2009 to November 2009), a total of 150 patients aged ≥18 years were consented following an institutional review board–approved protocol. All patients had a diagnosis of SCD (homozygous sickle cell disease, double heterozygous for hemoglobin S and hemoglobin C, double heterozygous for hemoglobin S and β thalassemia, or double heterozygous for hemoglobin S and hemoglobin O Arab) and were enrolled at their baseline state of health, defined as no acute vasoocclusive crisis within the previous 30 days. Exclusion criteria included an independent current diagnosis of psychosis, depression with psychosis, or a comorbid disorder with psychosis as a primary symptom as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; active abuse of alcohol or illegal drugs; concurrent chronic systemic disease; and the inability or unwillingness to participate in the study.

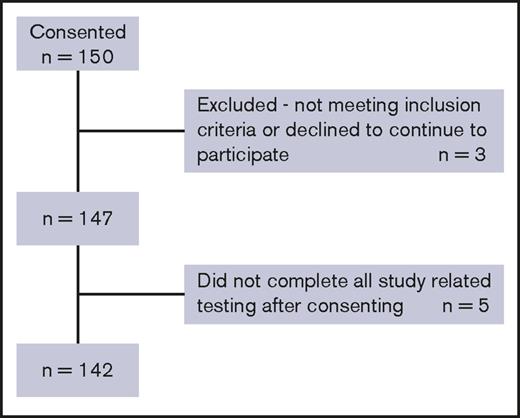

A total of 142 patients completed the study, and their data were analyzed (Figure 1). Clinical and medical histories were obtained using a standardized data collection form. At enrollment, patients completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) and performed a computerized neurocognitive test (CNS Vital Signs [CNSVS]). Six months later, patients returned to complete the BDI and SF-36 forms, and their medical data were updated. During the study period, patients were asked to complete a daily pain diary for 7 consecutive days on a monthly basis for 6 months. Data on medical utilization and costs were collected over a period of 1e year prior to and up to 6 months following study entry (supplemental Figure 1).

BDI

Although not specifically validated in SCD, the BDI was previously used for assessment of depression in SCD.22 The BDI consists of 21 self-report items, rated on a scale of 0 to 3. The sum of individual items provides an index of depression, with higher scores corresponding to greater depression.24,25

In this study, SCD patients were categorized into those without depression (BDI score <14), and patients with depression (BDI score ≥14 or BDI score <14 while actively receiving therapy for depression). Patients with depression were further subdivided to those with moderate depression with a score of 14 to 25 and those with severe depression with scores of 26 to 63.

The BDI score was previously modified in other patient populations based on expert opinion.26 In end-stage renal disease, a chronic disease similar to SCD, the BDI was used to screen for depression with a cutoff of 14.27 Compared with the gold standard and other screening tools, the BDI with this cutoff had the best diagnostic accuracy. The cutoff of 14 had a sensitivity of 62% (95% confidence interval [CI], 43%, 81%), specificity of 81% (95% CI, 72%, 90%), a positive predictive value of 53%, and a negative predictive value of 85%.

HRQoL

We assessed HRQoL outcomes using the SF-36 measure.28 The SF-36 has been validated in populations with chronic diseases29,30 and in patients experiencing chronic pain similar to SCD patients.31 In adults with SCD, HRQoL was previously assessed using the SF-36 in large clinical studies,12,32 and it has been validated against 2 other quality-of-life measures in SCD patients.33

The SF-36 Health Survey consists of 36 items that cover 8 sections consisting of physical functioning; role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, general health, vitality, and social functioning; and role limitations due to emotional problems and mental health. The scores from the 8 sections are combined into 2 summary scores; physical HRQoL summary and mental HRQoL summary. The first 4 sections (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, and general health) represent physical HRQoL, while vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health reflect mental HRQoL.

Medical history

Demographic information, including education level, marital status, household size, income, profession, and insurance coverage, was obtained from electronic medical records and patient report at the enrollment visit. Simultaneously, a physical examination was performed, and a detailed medical history was obtained from the patient and chart review, including SCD-related and unrelated medical history, pain history, number of hospitalizations and emergency room visits during the previous year, surgical history, transfusion history, and prescription medications, including analgesics and antidepressants. On the second visit, a physical examination was repeated and medical history was updated. Laboratory tests were obtained as a mean of 3 results obtained at the enrollment visit and at the 2 most recent outpatient visits.

Disease severity

Disease severity was assessed using a modified version of a previously validated chronic disease severity score, where 1 point is given for each of the following: pulmonary dysfunction as defined by the presence of pulmonary hypertension or oxygen saturation <92%; avascular necrosis of the hip or shoulder; central nervous system abnormality, as defined by a history of stroke, seizure, or transient ischemic attack; kidney dysfunction, as defined by proteinuria (1+ on urinalysis) or creatinine >1.0 mg/dL; and a history of leg ulcers. The total score was interpreted on a scale of 0 (mildest disease) to 5 (most severe disease).34

Computerized neurocognitive test

At enrollment, a computerized neurocognitive test (CNSVS; Morrisville, NC) was administered over 30 minutes to assess composite memory, psychomotor speed, reaction time, complex attention, and cognitive flexibility. This self-administered test has not been specifically validated in SCD but was previously used for screening for neurocognitive functions in this patient population. The CNSVS test battery consisted of the following tests: verbal and visual memory, finger tapping, Stroop test, symbol digit coding, shifting attention, and continuous performance. Test scores reflect the following domains: verbal memory, visual memory, cognitive flexibility, reaction time, processing speed, executive function, motor speed, and simple visual attention.35

Pain diaries

At enrollment, patients were asked to fill out pain diaries for the first week, on each month of the study, either on paper or electronically. Patients were called or e-mailed monthly to remind them to fill out their diary for 1 week. Patients were asked to record the date and time they took pain medication, the name of the medication and dosage, the pain location, and the pain level on a scale of 1 to 10 (10 being the greatest pain). They could either return paper diaries by mail in stamped addressed envelopes that were provided or return them electronically. Patients were reminded by telephone monthly to return their diaries.

Health care costs and utilization

Cost accounting and administrative physician billing records were obtained only from patient utilization at the Duke University Health Care System, because most of the patients’ health care occurred at this institution, and the possibility of obtaining reliable, standardized data from other institutions attended by a small number of patients was low and unreliable. Cost and medical utilization details were collected for each patient, starting 1 year before enrollment date and up to 6 months following study entry. The data included resource use and corresponding costs, number of hospital admissions, number of emergency department (ED) visits, number of outpatient visits, and the number of inpatient days. The total associated costs (including laboratory tests, radiology tests, and other miscellaneous inpatient, ED, and outpatient procedures) were calculated. Indexing on the enrollment date, prospective data were collected for 6 months, which was the longest follow-up period available at the time of billing data retrieval.

Statistical methods

Baseline characteristics were compared between SCD patients with depression and SCD patients without depression. P values were obtained using Student t test for continuous variables (such as age and body mass index [BMI]), and χ2 and Fisher’s exact statistics were used for categorical variables (such as sex, age groups, SCD diagnosis, severity score, and insurance status) (Table 1). Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Analysis of covariance was used to compare HRQoL outcomes in patients with and without depression, controlling for other variables. The following measures were included in the analysis as covariates: sex, SCD genotype, educational level, current hydroxyurea therapy, current opioid therapy within 30 days of enrollment (eg, oxycodone HCL, methadone, morphine sulfate extended release [MS Contin], or fentanyl patch), and a mean of the most recent 3 counts of hemoglobin, hematocrit, white blood cells, and platelets.

Descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation, were computed to describe the demographics of the population studied and to summarize the BDI, SF-36 V2, and CNSVS 7 continuously scaled neurocognitive domain scores.

A 2-sample t test (Welch’s test assuming unequal variance) was used to compare continuous variables, and a Pearson χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables and proportions. A 2-tailed Fisher’s exact test was used for cell counts with <5 observations. Disease severity scores were assessed using a cumulative predictive model.

P values ≤ .05 were considered statistically significant.

To evaluate the relationship between the BDI and CNSVS data, we applied generalized linear models (GLMs) with depression and HRQoL as predictors for each of the neurocognitive functional domains outcomes.

The measures in the GLM were fit and adjusted for age, sex, education, genotype, and opioid use. A Student t test and PROC GLM were performed in SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute). Further analysis and graphs were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0d (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Unadjusted resource use and direct costs were compared between the 2 study groups before and after assessment of depression. Given the skewed distribution of the resource use and cost variables, P values comparing the differences between depressed and nondepressed patients were obtained using GLM with negative binomial error distributions and log link functions for days per admission inpatient days, number of hospital admissions, ED visits, and outpatient visits. GLMs with γ error distributions and log link functions were used to compare total inpatient, ED, and outpatient costs between patients with depression and without depression. The models included covariates for age and sex. The findings were reported as counts of resource use and medical costs for depressed relative to nondepressed patients along with 95% confidence intervals and corresponding P values.

Results

Population demographics

Ninety-five percent (142/150) of patients who consented completed the study. Five patients dropped out, and 3 did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria after consenting (Figure 1). A total of 160 patients were approached, and 10 declined to participate. Sixty-one of 142 participants (43%) were male, and the mean age at enrollment was 34.2 ± 12.6 years. SCD genotypes are shown in Table 1.

Socioeconomic data

Socioeconomic data were obtained for 140 patients. Almost one-quarter (24%) of the patients had a household size of 4, 21% had a household size of 3, one-third (29%) shared living space with another individual, and 18% lived alone. Most of the patients were single (68%), and 19% were married; the rest of the patients were either divorced or separated. There was no statistical difference in the marital status of those with and without depression. The large majority (87%) of patients reported an annual household income between $2500 and $25 000. The poverty threshold for a 4-member household (24% in this study) in 2009 was $22 050.36 No reported income difference was noted between those with and without depression (data not shown). One-quarter of the enrolled patients (25%) were employed full time, and 60% received disability benefits.

Depression

Fifty patients (35.2%) were found to have depression; 37 patients (26%) had clinical depression as measured by BDI score ≥14 and 13 patients (9%) had a BDI score <14 but were actively receiving therapy for depression and were thus included in the depression group. Of the 81 women included in the study, 36 (44.4%) had depression, and of the 59 men included, 12 (20.3%) had depression (P = .0038). Forty-nine percent of patients without depression were female, and 51% were male. BMI was not significantly different between depressed and nondepressed patients (42.4 vs 31.9, respectively; P = .27). The mean age was 35.4 years for depressed patients and 33.7 for nondepressed patients (P = .44). The prevalence of depression was not statistically different among SCD genotypes (P = .18).

Quality-of-life outcomes

Quality of life rather than disease severity was the measure most strongly related to depression in this study (Tables 1 and 2). Depression was significantly related to physical quality of life (P < .0001); a higher depression score was associated with a lower physical quality-of-life score (Figure 2). Depression was also significantly related to mental quality of life (P < .0001); a higher depression score was associated with a lower mental quality-of-life score (Figure 3).

The relationship between depression and physical quality-of-life outcomes. HRQoL. Depression is defined as a reported BDI score of ≥14 or a BDI score of <14 while actively receiving therapy for depression. No depression is defined as a BDI score <14. Moderate depression is defined as a BDI score of 14 to 25. Severe depression is defined as a BDI score of 26 to 63.

The relationship between depression and physical quality-of-life outcomes. HRQoL. Depression is defined as a reported BDI score of ≥14 or a BDI score of <14 while actively receiving therapy for depression. No depression is defined as a BDI score <14. Moderate depression is defined as a BDI score of 14 to 25. Severe depression is defined as a BDI score of 26 to 63.

The relationship between depression and mental quality-of-life outcomes. HRQoL. Depression is defined as a reported BDI score of ≥14 or a BDI score of <14 while actively receiving therapy for depression. No depression is defined as a BDI score <14. Moderate depression is defined as a BDI score of 14 to 25. Severe depression is defined as a BDI score of 26 to 63.

The relationship between depression and mental quality-of-life outcomes. HRQoL. Depression is defined as a reported BDI score of ≥14 or a BDI score of <14 while actively receiving therapy for depression. No depression is defined as a BDI score <14. Moderate depression is defined as a BDI score of 14 to 25. Severe depression is defined as a BDI score of 26 to 63.

Physical quality of life.

When testing the physical quality of life score vs depression, sex, age, and socioeconomic factors, both sex (P < .0001) and receiving a disability benefit (P = .03) were significant. Physical quality-of-life scores were lower for women than men and lower if the patient received a disability benefit, adjusting for the other variables.

Mental quality of life.

When testing the mental quality-of-life score vs depression, sex, age, and socioeconomic factors, sex was significant (P < .0001). Mental quality-of-life scores were lower for women than men, adjusting for the other variables.

Disease severity

Of the 142 enrolled patients, 34 (24%) had a severity score of 0, 54 (38%) a score of 1, 31 (21.8%) a score of 2, and 16 (11.2%) had a score of 3. No patients had a severity score of 5, and only 7 (5%) had a score of 4.

Hemoglobin was significantly related to the severity of disease (P = .009). The cumulative logistic model indicated that higher hemoglobin levels correspond to lower severity of disease levels.

Sex was also a significant predictor of severity of disease (P = .004), with males more likely than females to have more severe disease. However, severity scores were not significantly different in patients with depression and those without depression (1.29 ± 1.08 vs 1.46 ± 1.16, P = .72).

Neurocognitive functions

There was no significant difference in neurocognitive function scores between patients with and without depression when tested for the following 5 domains: memory, psychomotor speed, reaction time, complex attention, and cognitive flexibility.

Pain diaries

Overall, there was poor compliance with pain diaries; 21% of study participants (30) did not return any diary, and 40% returned only 1 or 2 diaries. Only 6% completed all 6 diaries, and, interestingly, 4% completed >6 diaries, for an average of 9 diaries (Table 3). Due to the poor compliance and the variability in the data collected via diaries, these data were not analyzed.

Health care costs and utilization

The mean number of hospital admissions was not statistically different in patients with depression and those without depression (1.2 vs 0.6, P = .06) in the 12-month period prior to study enrollment and the 6-month period following enrollment (0.6 vs 0.4, P = .35) (Table 4). The mean number of ED visits and outpatient visits were similar between SCD patients with and without depression during both time periods.

In the 12-month period prior to the assessment of depression, the overall costs were significantly higher ($30 665 vs $13 016, P = .01). Similarly, in the 6-month period following assessment of depression, the total health care costs were significantly higher among patients in the depressed group than those in the nondepressed group ($13 766 vs $8670, P = .04) (Table 4).

Including physician fees paid, both the total inpatient costs and total overall costs were significantly higher for patients with depression than those without depression for the 12-month period before study enrollment (ratio of mean inpatient costs adjusted for age and sex: 2.2; 95% CI, 1.1−4.5; P = .02.). The adjusted total average costs were 1.9 times higher for the depressed group than the nondepressed group (95% CI, 1.2-3.2; P = .01).

Correlation between health care utilization before and after diagnosis

The correlation between inpatient days in the 12 months prior to diagnosis and 6 months postdiagnosis is 0.46 (P < .0001), and the correlation of total cost prior to and following diagnosis is 0.44 (P < .0001).

Discussion

The prevalence of depression in sickle cell patients in this study is ∼5 times as high as that of the general population, and depression was significantly associated with worse mental and physical HRQoL outcome scores. Health care utilization and inpatient costs were significantly higher in depressed patients than nondepressed patients during the 12-month period preceding the diagnosis of depression. Similarly, overall costs were significantly higher in the 12 months preceding enrollment and during the 6 months following study enrollment.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, the prevalence of depression in US adults for the years 2004-2008 ranged from a high of 7.9% in 2004 to a low of 6.4% in 2008.5 The prevalence of depressive symptoms in SCD patients is also high when compared with the general African American population.9 In addition, adults with SCD who report more frequent painful episodes are more likely to report depressive symptoms.37 Available evidence shows that affective disturbance and psychosocial factors are involved in negative medical outcomes, including increased frequency, duration, and intensity of painful episodes and adverse psychosocial consequences in patients with SCD.7,11,38-40 Further, negative or maladaptive cognitions, a particular feature of depression, are associated with poorer medical outcomes, passive adherence to medical directives, increased levels of psychological distress, and decreased capacity to cope with pain.38,41-43

Our data show that one-third of SCD patients had clinical depression. Of these, 72% were women, which is similar to 65% found in the general population.5 Prevalence of depression by age group in this study also mirrors the pattern of prevalence in the general population, with a higher prevalence in the younger age groups and a lower prevalence among those aged >50 years.44

The cutoff of 14 was determined following discussion with the psychologists at Duke Sickle Cell Center, based on the long clinical experience with SCD patients. When used to screen for depression in end-stage renal disease, a chronic condition similar to SCD, this cutoff showed the best diagnostic accuracy (76%) compared with other cutoff values. Compared with the gold standard and other screening tools for depression, it had a high positive likelihood ratio (+LR). A +LR reflects the odds at which a given cutoff of a depression screening tool is likely to be present in a depressed vs nondepressed patient. Thus, the high +LR of BDI with a cutoff of 14 increases its reliability as a screening tool for depression.27

Previously, depression was found to be associated with a higher BMI in the general population.45-47 The association could be unidirectional or bidirectional, with depression causing stress metabolism dysregulation and obesity or obesity itself leading to the development of depression through negative self-image.47 We found no significant association of BMI with depression in this study population. Of note, the mean BMIs for depressed and nondepressed patients (42.4 and 31.9 kg/m2, respectively) were above the cutoff for obesity as defined by the WHO (BMI >30 kg/m2).

A study of non-SCD patients with depression found that sociodemographically disadvantaged patients with greater medical and depressive illness burden are at a high risk for poorer quality-of-life outcomes.48 In SCD, the PISCES investigators found an association between the diagnosis of depression in SCD and lower quality-of-life outcomes on all 8 subscales of the SF-36.37 The SCD Consortium report found HRQoL outcomes to be significantly worse on all subscales in adult SCD patients than in the general population.49 Further, a strong association was found between the use of antidepressants, reflecting a diagnosis of depression and worse HRQoL outcomes on all scales except mental health. Similarly, we found patients with clinical depression had poorer physical and mental quality-of-life scores. In Brazil, a report on 110 SCD patients found that one-third had depression, and this drove the HRQoL scores lower in this subgroup.50 In a cohort of children and adolescent SCD patients, depression was also associated with worse HRQoL scores in all domains.51

Depression was found to be associated with neurocognitive deficits in other patient populations.52,53 However, assessment of neurocognitive functions showed no difference between those with depression and those without depression in this study, perhaps because this population in general has altered neurocognitive functioning due to SCD-associated neurological complications. Of 70 patients for whom data were available, 23% had a history of central nervous system events.

Health care costs in SCD are substantial. In 1996 dollars, the estimated total direct cost of hospitalizations per year for people with SCD was $475.2 million.18 If updated for 2012 dollars, the estimate cost surpasses $860 million. The average cost per hospitalization per SCD patient in Maryland in 2003 was $6656 ($9296 in 2012), and the total cost of hospitalizations for the state was $15.7 million ($21.9 million in 2012).54 During the most recent year for which we have data (2008), our Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center saw 1061 SCD patients, of whom approximately 60% were ≥18 years. These patients accounted for approximately $11 million ($12.5 million in 2012) in medical charges. Approximately 12.5% of charges were derived from ED care, 68.6% from inpatient charges, and 18.9% from outpatient charges (S.D.R. and L.M.D.C., unpublished data). However, these figures do not represent all the care provided to these patients, since many of our patients also receive care at other regional hospitals, EDs, and local doctors offices. Nevertheless, care for an average patient at our center generated a mean of over $10 000 ($11 400 in 2012) in health care charges per year.

The relative risk of high hospital utilization was found to be 2.8 times higher in SCD patients with a diagnosis of depression compared with nondepressed patients.23 Similarly, SCD patients with depression had a frequency of hospitalization of 2.85 per year compared with 1.83 hospitalizations for those without depression.23 In this study, total average health care costs (including inpatient, ED, and outpatient costs) were higher in the depression group, both before and after assessment of depression. In the 1-year period prior to study entry, total medical costs for SCD patients with depression were more than double that of nondepressed group ($30 665 vs $13 016; P = .01). In the 6 moths following assessment for depression, total health care costs remained significantly higher in the depressed group ($13 766 vs $8670, P = .04). Although there was no formal intervention, study participants discussed their assessment results with the health care provider during their study visit. Study participants were also encouraged to talk to the social worker or were referred to a mental health provider when appropriate.

Inpatient care was a significant cost driver. Inpatient costs for the nondepressed group stayed roughly the same, accounting for 58% of total costs in both the 12-month period prior to study entry and in the following 6-month period. For the depressed group, however, inpatient costs made up 84% of the total costs in the depressed group prior to the assessment of depression and 74% after the assessment of depression. Inpatient costs were significantly higher in the depressed group in the year preceding enrollment, despite a nonsignificant difference in number of inpatient days. A study based on data derived from a cohort of 12 365 inpatients found that overhead charges, but not number of inpatient days, account for the bulk of the overall cost of hospital admission.55

Clinical experience shows that patients who have clinically stable SCD and without significant comorbidities tend to keep scheduled outpatient visits or are better able to manage their disease with outpatient care rather than seek care provided in the ED or hospital settings.

In this study, we enrolled patients only in the clinic and did not recruit through the ED or day hospital, which may have resulted in a bias toward enrolling patients who are more compliant to clinic visits or who have less severe disease. However, we enrolled over a 9-month period, which was a sufficient time span to allow most patients, even those infrequently seen, to attend clinic visits and participate in the study. Enrolling over a 9-month period also allowed most patients who had experienced an acute vasoocclusive event to participate in the study. Even though patients could not participate within 30 days of the vaso-occlusive event, there was sufficient time for them to return to clinic and participate in the study beyond the 30 days. This exclusion criterion was chosen to minimize the effect a recent vaso-occlusive may have on the assessment of depression and quality-of-life questionnaires. However, excluding those who have frequent vaso-occlusive episodes may have resulted in patients with more severe disease being excluded, thus affecting the representativeness of the population.

Limitations of our study include the inability to ascertain the time of onset of depression. Thus, we were unable to distinguish between patients who had depression throughout the 1-year period prior to study enrollment and those who developed depression within that year. It is possible that acute events associated with hospitalizations in the year prior to assessment could have been associated with preexisting depression or may have represented events that contributed to the onset of depression. Comparisons of resource use and costs were complicated by (1) sporadic occurrence of acute complications in SCD patients, (2) differences in disease severity among sickle genotypes, (3) a relatively short study time window (6 months), and (4) lack of availability of medical resource use and cost data for non–Duke University Health Care System provider visits, tests, and procedures or for any admissions to other hospitals that may have occurred. Although the duration of depression prior to the index date was unknown, medical care utilization and cost data over the 12 months prior to enrollment in the study were used to evaluate whether similar patterns of resource use and costs occurred prior to the enrollment date in the depressed and nondepressed cohorts. We did not expect to see any significant difference between the 2 time periods, although we did hypothesize greater medical costs in depressed vs nondepressed patients with SCD.

Conclusion

Mental health is an integral part of the comprehensive management of this patient population. Our results highlight an important but inadequately studied aspect of SCD. Data from this study confirm the high prevalence of depression in adults with SCD and its association with lower physical and mental quality-of-life scores. Furthermore, these results endorse the hypothesis that SCD patients with depression incur higher total health care expenditures than SCD patients without depression.

Additional efforts should be exerted for prevention, early diagnosis, and therapeutic intervention to reduce the impact of depression on SCD patients and improve HRQoL outcomes. Further elucidation of the degree of association and causal relationship is critical to formulating interventional approaches designed to treat depression in the setting of SCD. These approaches would likely result in improvement of health care outcomes in SCD as well as similar chronic illnesses.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank SCD patients and families for their support and dedication to research.

This study was supported by the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (grant R21 HS17645-02).

Authorship

Contribution: S.S.A. designed the research, performed the research, and drafted the manuscript; C.M.F. performed the research and codrafted the manuscript; S.K. analyzed the data and codrafted the manuscript; M.J.T. codrafted the manuscript; S.D.R. designed the research, analyzed the data, and codrafted the manuscript; and L.M.D.C. designed the research, analyzed the data, and codrafted the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Soheir S. Adam, Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3939, Durham, NC 27710; e-mail: soheir.adam@duke.edu.